The Tragic Details Of The Hall-Mills Murders

In modern times, certain court cases can capture the entire country's — and sometimes the world's — attention. Think of the O.J. Simpson or the Casey Anthony trials, for instance. Thanks to the internet and 24-hour cable news, it's easy to assume that this is a new phenomenon, but it isn't. Back in the 1920s, several trials commandeered headlines in much the same way.

In 1924, there was the highly publicized trial of Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, two men from wealthy families who murdered a 14-year-old in Chicago, which was a sensation in the press, per Northwestern University School of Law. However, it wasn't just lurid murder cases that enthralled the public. In 1925, we saw what became known as the Scopes Monkey Trial, a case that featured William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow trading courtroom barbs over the legality of teaching evolution in schools, according to NPR.

Another trial that was plastered across the front page of newspapers everywhere was the trial of Frances Hall and her brothers, Henry and Willie Stevens. All three were implicated in the murder of Hall's husband and his alleged lover. The case was somewhat unusual in that it didn't only become newspaper and tabloid fodder — it was essentially brought about by the tabloids themselves.

The bodies are discovered

According to The Yale Review, on the morning of September 16, 1922, a 23-year-old man and his underaged 15-year-old girlfriend were walking along a road in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Off in the distance, they saw a man and a woman lying under a crabapple tree. They were both well-dressed, and the woman lay with her head on the man's knee while he appeared to take a morning nap by placing his Panama hat over his face. This wouldn't have been too unusual given that the road the man and his girlfriend were walking on was often used by young couples as a lover's lane. The problem in this instance was that the man and woman lying beneath the tree were both quite clearly dead.

The man and his girlfriend rushed off to tell someone about their gruesome discovery. They called the police, who were on the scene within minutes. It didn't take them too long to figure out who the two victims were, and it appeared that's how the killer — or killers — wanted it because they left the man's business card leaning against his foot. The victims were Reverend Edward Wheeler Hall and Eleanor Mills.

The victims

Reverend Edward Wheeler Hall was the pastor at a local church and was well-known throughout the community. What instantly made his death salacious in the eyes of onlookers was the woman he was found dead with — Eleanor Mills, who wasn't his wife. His wife was Frances Hall, a woman who came from one of the area's most well-known families, per The Yale Review.

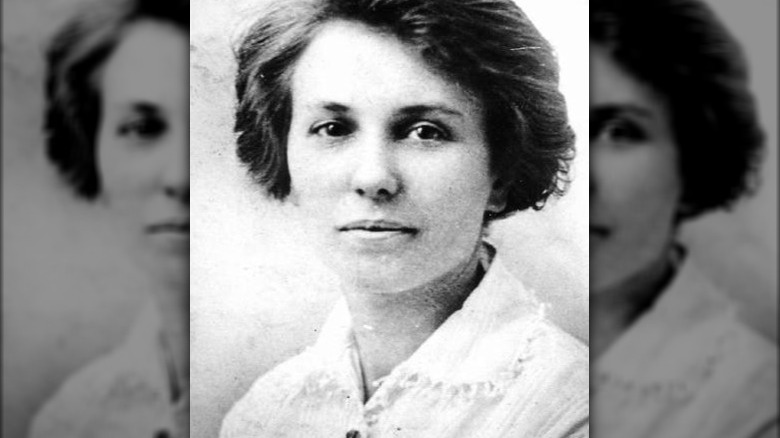

The other victim, Eleanor Mills (pictured above), was an attractive 34-year-old woman who was a member of Hall's church and sang in the choir. The fact that the two were found dead together appeared to solidify rumors suggesting that something was going on between the pair. According to Dr. Mary S. Hartman, the Dean of Douglas College at Rutgers University, both Hall and Mills had been missing for two full days before their bodies were discovered.

Mills' skull was riddled with three bullet holes, while Hall's skull had one. Mills' throat had also been slashed, and a few years later, when the case went to trial, it was revealed that her vocal cords and tongue were removed. There were also rumors that both bodies had been sexually mutilated, but no official reports corroborate that. An array of love letters between the two were scattered around their bodies, all but confirming the two had engaged in some kind of relationship.

The investigation fizzles

According to The Yale Review, one of the investigators working on the case was quoted as saying that "the case is a cinch" and would be solved in no time. In fairness, given the initial facts of the case, it did seem like it had everything it needed for the police to make quick work of the investigation. There was what appeared to be an affair and a jilted wife in Frances Hall, who also happened to have two brothers, one of whom was known around town as a deadeye shooter. According to The New York Times, investigators even had a second option to turn to: Mills' husband, Jimmy Mills.

Even with no shortage of possible suspects and a grotesque crime scene with what appeared to be stellar clues — namely the love letters — the investigation went nowhere through the rest of 1922 and eventually petered out completely. It wasn't until four years later, when a tabloid newspaper needed to up its sales figures, that the case started moving again.

The Daily Mirror brings the story back to the public eye

By 1926, the case was at a complete standstill when a new piece of anecdotal evidence emerged. According to Rutgers University, Louise Geist had been a maid in the home of the well-to-do Halls. Four years after the murders, her husband filed an annulment petition that specifically cited the fact that his wife had withheld information about the Hall-Mills murders. The claim was that Frances Hall told Geist on the day of the murder that she knew that her husband planned to run off with Eleanor Mills. Furthermore, Geist allegedly went to the road where the bodies were found along with Hall and her brother, Willie, and was even paid several thousand dollars to stay quiet.

Meanwhile, William Randolph Hearst's New York City-based tabloid newspaper, The Daily Mirror, needed a way to increase its readership. When word came out about the new details in the Hall-Mills murders, the publication released a barrage of articles that reignited interest in the case among both readers and investigators. The Daily Mirror saw their numbers jump, and the case was reopened. It wasn't too long before Hall and her brothers were charged with the murders, per The Yale Review.

The case goes to trial

Given that The Daily Mirror was largely responsible for bringing the case back from cold case files, it seems somewhat fitting that the trial that followed was a tabloid rag's dream. However, other major papers assigned reporters to cover the case, too, with The New York Times even sending a team of four, per The Yale Review. The trial featured all kinds of fodder, including the love letters between Edward Wheeler Hall and Eleanor Mills being read into the record and even Frances Hall herself taking the stand in her defense. On the stand, Frances' relaxed demeanor earned her the nickname The Iron Widow.

A character in the trial with a far less flattering nickname was Jane Gibson, who became known to history as The Pig Woman, per Rutgers University. She lived on a farm and raised pigs, hence the nickname. Gibson became an important witness in the case as she alleged that she had seen the murder take place while hiding in an attempt to catch whoever had been stealing her corn. Adding to the spectacle was the fact that by the time the case went to trial, Gibson was practically on her death bed, withering away from a bout with cancer, and had to be wheeled into the courtroom on a stretcher and constantly tended to by a medical team.

The case lasted for three weeks, and while it had all makings of a proper spectacle, it lacked hard evidence. Hall and both of her brothers were acquitted. To this day, the case remains unsolved and is largely forgotten about, despite the international attention it received at the time.