What Did Ancient Romans Believe About Ghosts?

Humans have been obsessed with ghosts for millennia. It makes sense, given that we're pretty universally spooked by the thought of death and what may or may not come afterward. Ghosts can offer a way to manage that fear and mold it into a shape that makes sense within our time and culture, according to Aeon. Given that line of thought, then, it's no wonder that stories of ghosts have been around since nearly the beginning of recorded history.

That's no exaggeration. As the World History Encyclopedia notes, ghost stories can be found in ancient Mesopotamia, China, Mesoamerica, and just about any society with the written word or a long-standing oral history tradition. Given that long history, it wouldn't be shocking to learn that Neanderthals and early modern humans also told scary tales of the returned dead, perhaps haunting the back of a lonely cave somewhere.

The ancient Romans were certainly no exception here. Sure, they could be eminently rational when it came to feats of engineering or military strategy, but they also had a deeply spiritual side that had room for phantoms of all sorts. In fact, they held a diverse array of beliefs that point to a complicated view of ghosts, spirits, and the afterlife. Here's what the ancient Romans really believed about ghosts.

Romans had many ideas about what happened after death

Much like today, there were probably about as many versions of the ancient Roman afterlife as there were ancient Romans to ask about it. Oh, and also ancient Greeks. As Encylopedia.com notes, much of Roman culture and religious belief that was recorded was based on earlier Greek culture. Well, it was based on Roman preconceptions of Greek culture, which were largely based on Greek literature and also apparently the culture of the nearby Etruscan people. Any of the more unique pre-copycat beliefs of early Rome weren't terribly well recorded.

According to The Collector, ancient Romans did generally believe that there was some sort of underworld that acted as the final destination for most spirits. Any previous humans who couldn't make it across the river Styx separating the land of the living from that of the dead might become a ghost. Some were believed to become minor deities, while dead emperors were sometimes deified. Whether the regular Roman really believed that Julius Caesar and his ilk became gods in the afterlife or if they simply rolled their eyes at such fancies is less clear.

Roman ghost terminology got complicated

As vague and diverse as Roman beliefs of life after death got, so too were the words and concepts they used. According to "Haunted Greece and Rome," this variation can be frustrating, with different writers and historians sometimes claiming nearly opposite definitions for the same words. For instance, there seems to be a fair amount of confusion over lemures and larvae. Are they one and the same? Are the larvae restricted only to haunted house stories? The manes generally seem to be good or at least neutral spirits, unless you ask Roman historian Livy, who uses the term to describe some ghosts who have a vengeful edge to their goings-on.

It gets even more confusing when you realize that some writers, like Pliny and Virgil, used a plethora of terms for literary effect. They were writers, after all, and it hardly behooves a poet to use the same old boring word for ghost over and over. Ultimately, it makes a little more sense to just go with the flow and pay attention to the story itself, with the different terms as signposts instead of strict categories.

Lemures were usually troublesome ghosts

If an ancient Roman person were to run across a lemure, then they were all but bound to be in trouble. At least, that's how the early Christian writer St. Augustine interpreted things, writing (via ThoughtCo) in his "City of God" that lemures (which were also sometimes called the larvae) are "hurtful demons made out of wicked men." Other interpretations maintain that the lemures were the spirits of people who had been taken from the world in a sudden, violent manner. They might linger in houses or other locations and even push the living to insanity.

Dig a little deeper, however, and the reputation of these supposedly evil ghosts becomes more complicated. "The Phantom Image" notes that second-century writer Apuleius characterized the lemures as less dangerous, claiming that they were instead relatively innocuous, especially if you were a virtuous person who tended to mind your own business.

Lares were supposed to be good spirits

Generally speaking, the lares were pretty safe ghosts to be around in the ancient world. Apuleius comes in again to muddy the spooky waters, writing that the lares were basically benevolent household ghosts or spirits that watched out for a given family. Only, he also equated them with the lemures, so you may or may not want to bring Apuleius along on your next ancient ghost hunt (via "Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds").

But he might have really been onto something, given that St. Augustine backs him up. As per ThoughtCo, he wrote in "City of God" that earlier writer Plotinus had noted that the lares were well-intentioned. In fact, according to Britannica, the lares were often interpreted as household gods, giving these ghosts a serious promotion to the family altar. There were even lares dedicated to larger community spaces, like neighborhoods and crossroads.

Manes were in a middle ground of ghosts

If you were to encounter a ghost and couldn't decide if it was clearly "good" or "bad," then you might make like St. Augustine and Plotinus did and toss the spirit into the catch-all category of "manes" (via ThoughtCo).

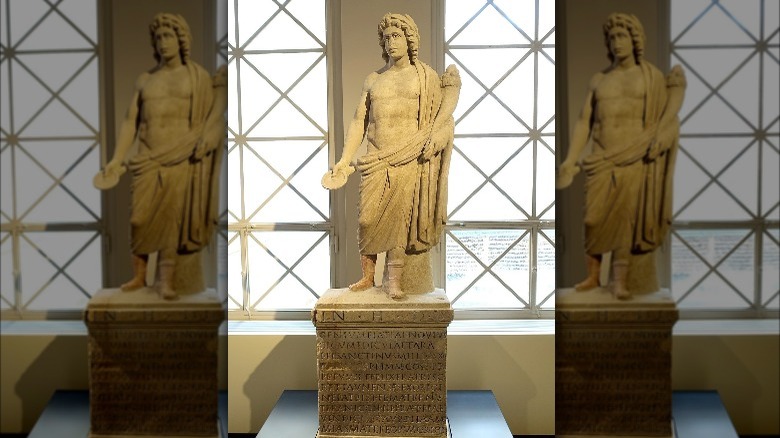

Manes were effectively ancestral spirits who existed in a gray area between humans and the gods, with the possible power to protect or guide the living, says the University of Oxford's Ashmolean Museum. The manes were associated with the underworld in that they were literally connected to the ground or to a space beneath the earth. Ancient Romans kept busy appeasing these particular ghosts since they could look out for their associated family or community — or potentially cause trouble if ignored for too long.

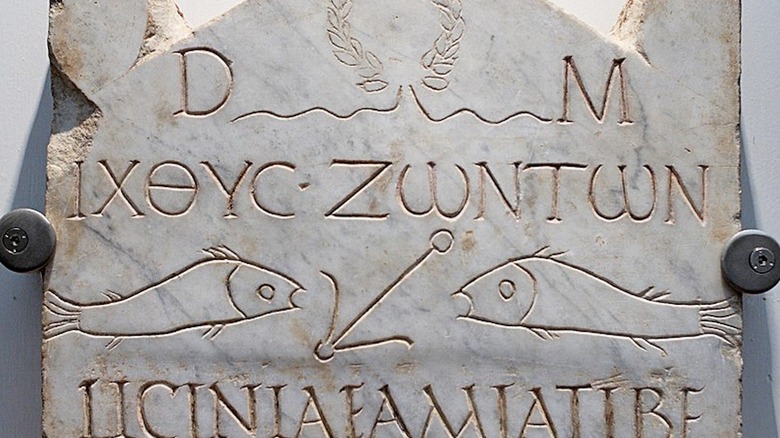

When a new spirit was on the way to join them — that is, when someone in the family died — their tombstone was usually marked by the initial "D.M." for "dis manibus" or "to the spirits of the departed." This was meant as a kind of heads up to the preexisting manes that a newbie was on the way and could use some care and guidance on the other side while they presumably adjusted to their new role as an ephemeral ancestor ghost.

A bad burial was a big issue for Roman ghosts

Like people in many other societies throughout history, the ancient Romans were very focused on properly disposing of a dead body. Failure to do so, whether through accident or malice, could result in a restless, unhappy spirit.

According to Encyclopedia.com, dead folks would ideally be mourned for about a week at home, where family members would eat only small amounts of food and occasionally call out for the deceased in a practice known as conclamatio. Cremation was the usual disposal method, but the ancient Romans would at least pay homage to the idea of burial, whether that meant sprinkling a bit of earth on the deceased just before the cremation or removing a small body part (like a finger) to actually bury. A son would dig through the ashes of his father; when he found a bone fragment, he could declare that dad was now one of the manes.

Of course, things couldn't always go to plan. People might die in a way that made burial or cremation all but impossible, or someone might deny them standard burial practices out of spite. According to Roman writer Tertullian, it was certainly a facet of ancient Roman belief. However, Tertullian was an early Christian who used the conceit of the angry untimely dead as a way of breaking down pagan belief, calling it and the magic associated with ghosts "deceit" (via "Magic, Witchcraft, and Ghosts in the Greek and Roman Worlds").

Dead ancestors were appeased by a set of rituals

If the ancient Romans assumed that the manes would look over them and their community, it was not meant to be a one-sided relationship. Even relatively benign spirits needed to receive proper acknowledgments, lest they deny help or even become hostile. So, how do you make an ancient Roman ghost happy? According to the Ashmolean Museum, that included a lot of offerings. Romans would leave food and drink at gravesites, hoping that these treats would get them in the good graces of their ancestors. Some memorials even included built-in cups that would allow wine, water, honey, and other liquid offerings to filter through the cremated remains below.

Everyday observances were also necessary, as the World History Encyclopedia reports, including both offerings and prayers. Special occasions, like weddings and the start or end of a household member's journey somewhere, necessitated some extra attention to get the lares in the protecting mood. More immediate family, who could be referred to as parentes if in reference to dead mothers and fathers, were often represented by statuettes. Those miniature representations of one's family, be they living or dead, could be bundled up and taken on a journey (perhaps with a bit of fire from the all-important home hearth) to bring both comfort and spiritual protection to the traveler.

Some Roman ghosts just wanted vengeance

Like so many modern ghosts, ancient Roman specters sometimes needed the living's help to set things right before they could move on and stop haunting folks. Wrongful death, especially where a murder was still free and unpunished, could be especially galling to a ghost. That sort of theme is exemplified in the tale of Tlepolemus, as related by Apuleius (via World History Encyclopedia).

Tlepolemus thinks everything is groovy, but while out hunting with his friend Thrasyllus, the other man murders him in cold blood. The reason? Thrasyllus wants Tlepolemus' wife. Having apparently passed off his friend's death as a hunting accident, Thrasyllus then goes about courting the wife. She turns him down, however, saying she's still in mourning for her husband. She's even less inclined to romantic overtures when the ghost of Tlepolemus appears to her in a dream and reveals the truth. She then drugs Thrasyllus, blinds him, and falls on her husband's sword at his tomb. As if that weren't enough for both Tlepolemus' ghost and the melodramatic Romans, Thrasyllus then makes his way inside the same tomb and starves himself to death there.

One wonders if their potentially shared afterlife — they are all in the same tomb, after all — got pretty awkward.

Ghosts were sometimes celebrated in Roman festivals

While daily obeisance was important for everyday spirits and ghosts like the manes and parentes, the Romans also kicked things up a notch on special occasions with ghost-focused festivals. Even the dead needed a bit of a party every once in a while.

For the naught and sometimes dangerous lemures, there was the Lemuria festival. According to ThoughtCo, it was typically celebrated in May on three separate days. Different observances often focused on ritual banishments and opening of the ways, such as walking barefoot, scattering black beans, and making sure that there were no knots in the vicinity to tangle up the proceedings. Some would also clang together pieces of brass, with the idea that the loud noise and accompanying words ("Ghost of my fathers, go forth!") would cause bad spirits to vacate the premises. Others would take the opportunity to please nicer spirits or, if they wanted to cover all of their bases, did a bit of everything.

As for the parentes and other ancestral spirits, there was also the Parentalia festival. That, as per the World History Encyclopedia, was a nine-day festival in February that culminated with a day for visiting graves and leaving offerings. The day after that was reserved for patching things up with one's estranged living relatives.

Some Romans called upon ghosts to fulfill curses

As if being dead weren't already enough of a task, some ghosts were harangued by the living to enact curses. Unlike many other things in the ephemeral world of the spirits, we have physical evidence of this practice. So-called "curse tablets" have been found in archaeological sites dating back to Roman Britain.

One set of inscribed lead and pewter tablets found in modern-day Bath can be linked to well over 100 individuals, as The Roman Baths reports. Those tablets were tossed into a local spring to reach a goddess, but that doesn't mean other, smaller spirits couldn't be roped in, too. According to the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents at the University of Oxford, Mediterranean curse tablets — scrawled with names, invocations, and pleas — were deposited in or around graves. The resting places of people who had died in especially violent or sudden ways were choice spots. Some rolled or folded tablets were even crammed into the tube that was supposed to carry offerings to the remains of the dead.

The idea was that the dead — perhaps turned into less-than-good spirits because of their method of death — would carry the message to evil spirits or would take on the tasks themselves. However, other communities seemed to steer clear of this practice, leaving their curse tablets in sacred spots or even buried in the floors of circuses and amphitheaters rather than bothering the potentially cranky deceased.

One early recorded ghost story has familiar elements

While some aspects of Roman ghost beliefs may seem strange, like pouring wine into someone's ashes or asking the dead to leave by clanging bits of metal together, other details may seem eerily familiar.

You may experience just such a familiar chill while reading the brief ghost story related by Pliny the Younger. As Pliny wrote, it all began when the philosopher Athenodorus arrived in Athens. He hears of an "ill-reputed and pestilential house" that's haunted by the ghost of a filthy, malnourished old man carrying a set of chains (Jacob Marley, anyone?). People living in the house risk serious mental harm and even death. It's soon abandoned and put on the market for a suspiciously cheap price. Athenodorus, his curiosity stoked, investigates. He stays in the house, keeps his cool when the ghost appears, and follows when it beckons, ending up in a seemingly innocuous spot in the home's courtyard. But when he directs others to dig there, they find human bones — bound by iron chains. They give the skeleton a proper burial, and the old man's ghost disappears.

Though the story is ostensibly set in ancient Greece, its inclusion in a Roman work indicates that it was interesting to Pliny's readers, in part because it echoed the importance of burial and remembrance in their society. Failure to pay proper respect to the dead might result in them returning, again and again, until someone finally fixed the problem.

Some Roman tales have people journeying to the underworld

Though the world of the ghosts often seemed insubstantial and out of mortal reach, some Roman tales insisted that the truly dedicated could travel to the underworld and interact directly with spirits. And, like so many things in Roman culture, it was largely cribbed from Greek mythology.

Think about all of the Greek heroes and mischief-makers who boldly walked into the underworld, from sad-sack Orpheus and Eurydice to repeat traveler Hercules (via ThoughtCo). Odysseus, the famously far-ranging king of Ithaca who we all read about in high school in Homer's "Odyssey," went there to get directions from the shades there, too, as ThoughtCo notes. So, it's no wonder that Roman poet Virgil sent his own Odysseus copy, Aeneas, there as well. Where Odysseus is trying to get home, Aeneas is trying to find a new one after the fall of Troy, with the help of his dead father. Both get what they're looking for, though at the cost of a thoroughly creepy interlude, while Virgil himself builds upon the previous Greek ideas of the underworld like a seasoned fanfiction author.