The Untold Truth Of This Historic WWII All-Black Female Battalion

During WWII, Americans from all walks of life came together to fight the evil Nazi war machine slowly engulfing Europe. However, racial tension in the United States was still a prominent issue, both domestically and in the service. Race riots broke out in Detroit and Los Angeles in the summer of 1943, and the U.S. government forcibly imprisoned over 120,000 Japanese Americans in squalid internment camps for several years.

Yet, Black Americans still played a huge part in the war effort, both domestically and as members of the U.S. Army. One of the most important Black units in the army was the 6888 Central Postal Directory Battalion, or "six-triple-eights," an all-Black and all-female unit. The 6888 was conceived in 1944, and shipped over to Britain and the European theater of WWII in early 1945. They were sent to help sort mail for the U.S. Army, and they served their country honorably and with distinction. Their famous motto was "No Mail, Low Morale."

Though they have a rich and fascinating history that is full of personal sacrifice, ingenuity, and bravery, they are unfortunately one of the understudied battalions in WWII and army history. This is the untold truth of the historic WWII all-Black, all-female, 6888 Central Postal Directory Battalion.

They faced discrimination within the army

In a shameful reflection of the history of discrimination in the United States, the 6888 faced constant racism during their service. The 6888, and all other Black and female battalions, were initially prohibited from even serving overseas (per the official WAC history). WAC director Oveta Culp Hobby refused to let them be stationed in Europe near Black troops, and it was not until private Black groups pressured the army that they relented in 1943.

In her memoirs, Lt. Col. Charity Adams Earley of the 6888 recalled an incident where a white officer segregated her and the other Black recruits from their white counterparts, which "shattered whatever closeness we had felt." When the 6888 went out to eat at an officer's club at Fort Oglethorpe in Georgia, the other diners called them racial epithets and left the restaurant in protest. In another incident, she recalled some U.S. Army personnel telling civilians in Britain that the Black recruits "had tails that came out at midnight," which caused curious citizens to come around the 6888 headquarters to see for themselves. Later, Adams recalled being told a white officer was going to take over her unit and show her how to handle it, to which she icily responded, "Over my dead body, sir." She was nearly court-martialed for the incident.

The 6888 survived Nazi attacks

On multiple occasions, the women of the 6888 found their personal safety threatened by the Nazi war machine, even though they were not in frontline or combat roles. On their initial journey from New York to Britain, German U-boats tailed them and almost sank their ship, the Ile de France. According to Brenda Moore's history of the 6888 in "To Serve My Country, To Serve My Race," many of the women on board the ship were incredibly frightened during the attack. One of the 6888, Myrtle Rhoden, described how the American ship had to "zigzag" away from the Germans during a tense 45-minute chase. Rhoden could hear an immense commotion outside her bunk, including horns, sirens, whistles, and people screaming, and the contents of her storage went flying throughout her room. Several recruits started crying and Rhoden herself thought the U-boat was going to sink them. Luckily, the boat was escorted by a large convoy, who successfully engaged the U-boat and guided the Ile de France safely to Britain.

Once they arrived in Britain, they experienced another close encounter. As they got off the ship, the Nazis fired a V1 rocket, or "buzz bomb," into a nearby area (per the Army National Museum). The women could hear the distinctive sound of the rockets, but luckily no one was killed or injured.

They received a warm welcome in Scotland

Though they experienced trouble with the Nazis during their journey and immediately after disembarking, the 6888 received a warm welcome when they arrived overseas. In early February 1945, the women disembarked from New York and arrived in Glasgow, Scotland, before traveling south to Birmingham, England. According to Brenda Moore in "To Serve My Country, To Serve My Race," during a ceremony for the unit put on just after they arrived in Birmingham, a 30-piece army band played the "Beer Barrel Polka" for them. The townspeople had gathered in the area and began to cheer the women on as they marched past. They arrived at their quarters at the King Edward School and morale was reported to be high.

According to Lt. Col. Charity Adams, the townspeople were not invited but had gathered spontaneously in an effort to show their support for the newly arrived 6888. She also commented on the difference in racial tension she experienced with the civilians in Britain compared with those at home in America. She noted that in Britain, the citizens referred to the 6888 as "Black" rather than "negro." In addition, Adams wrote that many of the recruits became friendly with British civilians, and they often requested permission to go over to their personal residences to relax and have fun.

They processed nearly 20 million pieces of mail in 3 months

The 6888 is known for processing a large amount of soldiers' mail, but the actual figures are truly unbelievable. During their time overseas in Britain alone, the 6888 was responsible for processing 17 million pieces of mail in just three months (per the Department of Defense). After their time in Britain, they went to France and cleared a backlog almost as large. According to "Double Victory: How African American Women Broke Race and Gender Barriers to Help Win WWII," the 6888 was responsible for the mail for all of the Americans in Europe, both civilian and soldier, about seven million people in all. They arrived in mid-February 1945 and got immediately to work, but they were sorting through Christmas gifts and letters sent months earlier.

The mail was piled high and filled three full airplane hangers (via the American Postal Workers Union). Some of the mail had been originally sent over a year before, meaning many of the recipients had likely died without receiving their last letters from loved ones at home. The 6888 worked 24/7 during their time in Britain and are estimated to have processed an astonishing over 8,000 pieces of mail per hour.

They had their own letters censored

Within the military, the control of information and communication is of paramount importance, and that's even more true during a time of war. Governments routinely surveil and censor letters coming from and going to the front, to make sure no sensitive information is released or disseminated. Because of this, in one of the least talked about aspects of the 6888's work, they were forced to censor some of the letters they processed.

Lt. Col. Charity Adams described the experience in her book "One Woman's Army." She said the task was "boring, boring, boring," and was only made more tedious by the massive volume of mail they had to deal with. Adams wrote that she initially felt a little uncomfortable reading the personal letters of strangers. Yet, she noted that the censors themselves became desensitized to the personal aspect relatively quickly, and she even felt that some of the more difficult letters may have been planted by higher-ups just to keep them busy.

Adams also was given the difficult task of censoring the mail of her own battalion. Some of the 6888 had apparently been consorting with known communist civilians in France, and army intelligence ordered their mail be looked at. One officer was to have all of her mail censored because she also had relatives back home who were allegedly communists, too.

The 6888 worked with German POWs in France

When the women of the 6888 arrived in England in early 1945, they ran into a long list of problems they had to deal with. Many soldiers and civilians had the same or very similar names, with Lt. Col. Charity Adams noting, "at one point we had more than 7,500 Robert Smiths." Just finding the troops could be an issue due to the constant troop movements and inadequate means of record keeping. The 6888 also found themselves constantly repairing poorly packaged items that were literally falling apart when they got them. Some people would address letters only to a recipient's first name, like Bill, U.S. Army, and the 6888 had to make sense of who that could be and where they needed to send it (per the American Postal Workers Union). The women ingeniously created information cards that not only tracked soldiers' movements, but also those of the civilian personnel whose mail they delivered, like Red Cross workers.

Surprisingly, during their time in France, the 6888 also worked with many German POWs (one pictured above). When Adams was in Rouen preparing the new living quarters for the 6888's arrival, she had 300 German POWs to do the hard labor of modernizing the outdated buildings. Once the 6888 arrived, the POWs still handled routine maintenance and carried the overloaded and heavy mail sacks.

Their working and living conditions were harsh

When the 6888 served in Britain and France they had to deal with very substandard living and working conditions. According to the Detroit News, the women had to deal with facilities that were segregated by both race and sex nearly everywhere they went. During their stay in Birmingham, England, the women worked in "rat-infested airplane hangars." The rats had been drawn to the hangars by the old and spoiled packages of food that had been rotting while waiting to be sorted (via the U.S. Department of Defense). Cheryl Mullenbach writes in "Double Victory" that the 6888 had to sleep on straw mattresses when they stayed in England.

Brenda Moore elaborates even more on the rough conditions in "To Serve My Country, To Serve My Race." Many of the women described their conditions at the King Edward School in Birmingham as terrible when they first arrived. The roof was full of holes and thus leaked; the heating was poor and hot water limited; and Cap. Noel Campbell Mitchell said the rooms were "small, ill-lighted, and poorly ventilated." At least initially, the women had to take showers outside in the cold February British weather. To make matters worse, they had to take them in groups and they did not have shower curtains, which led to at least one of them choosing to just use her helmet at her bedside instead.

Three members of the 6888 died in a car accident in France

The 6888 worked in many places during their service overseas in Europe, including both Great Britain and France. As noted by the National WWII Museum, the women arrived in Glasgow, Scotland, in early February 1945, to begin their overseas service. They soon traveled south to Birmingham, England, where they settled into their quarters and began processing mail. The women stayed in England until the end of the war, but almost immediately after Victory in Europe Day (VE Day), they went to La Havre and then Rouen, France to clear another massive backlog (per Cheryl Mullenbach in "Double Victory"). The women were surprised by the level of devastation they witnessed in France, which was a principal theater of the ground war and blitzkrieg.

It was during their time in Rouen that three of the women were killed in car accidents; Mary Bankston, Mary Barlow, and Dolores Browne, a group affectionately known within the 6888 as the "three B's" (via the New York Times). The unit raised money for the funeral themselves, and they were buried at the Normandy American Cemetery in France. Some of the members of the 6888 had been morticians before the war, and they prepared their friend's bodies themselves.

The women trained in jiu-jitsu

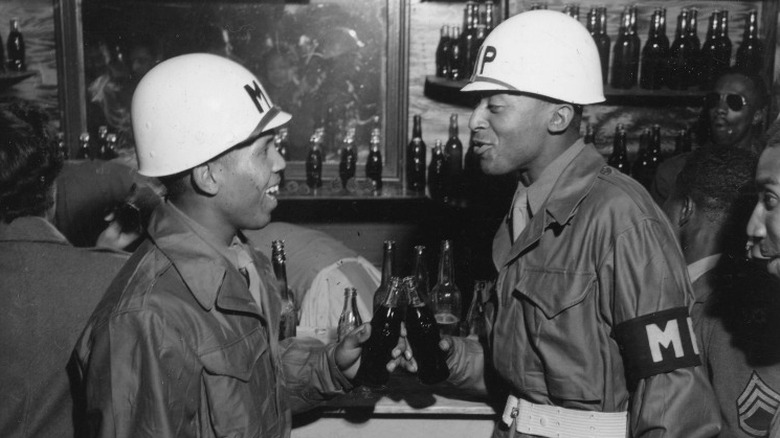

In a headline that could come straight out of modern battalion training, the women of the 6888 trained in jiu-jitsu during their time in the service. While in France, the women attracted a lot of attention, especially from Black male soldiers stationed in the area or returning from the front. According to Brenda Moore in "To Serve My Country, To Serve My Race," some soldiers would show up, grab women, and just start kissing them. Pvt. Gladys Carter recalled, "the whole place was jammed full of Black soldiers." Things got so out of hand that Cap. Noel Campbell Mitchell requested the use of military police (MPs) to take control of the situation (pictured above).

Lt. Col. Charity Adams, in her book "One Woman's Army," recalled asking that the MPs be allowed to carry firearms, but she was rebuffed. Instead, Adams turned to a British paratrooper who offered to teach the women jiu-jitsu as a means of self-defense. They scheduled classes for all of the women, and Adams felt extremely confident in their abilities to defend themselves. She noted examples of women taking down men much larger than then with ease.

Lt. Col. Charity Adams was the highest decorated Black U.S. female officer

The highest-ranking officer of the "six-triple-eights" was Lt. Col. Charity Adams Earley (pictured above, behind Cap. Noel Campbell Mitchell). Not only was she the first Black woman in the U.S. military, but she was also the highest-ranking Black woman in the military when she retired from the service in 1946 (per "An Encyclopedia of American Women During WWII"). Director of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) Oveta Culp Holley personally invited Adams to join the corps in June 1942, and she was a part of its inaugural class. Before the war, Adams had already graduated from Wilberforce University in Ohio, and she was pursuing a master's degree from Ohio State University (OSU) while simultaneously teaching school.

According to the National Museum of the U.S. Army (NMUSA), after the war, Adams returned to OSU and completed her master's degree in vocational psychology. She served as dean at both Tennessee State University and Georgia State University, and she founded the Black Leadership Development Program. Adam's wartime service has been honored in a variety of ways since her retirement in 1946, including by the National Postal Museum, National Women's History Museum, Ohio Women's Hall of Fame, Smithsonian Institute, and South Carolina Black Hall of Fame (via NMUSA). Adams died in 2002, and is today rightfully recognized as an outstanding soldier and true American hero.

The 6888 earned and received several medals

Since the end of WWII, the 6888 has received several U.S. Army and Congressional medals. On March 14, 2022, President Joe Biden signed into law the "Six Triple Eight" Congressional Gold Medal Act of 2021. The act officially awarded a Congressional Gold Medal to all veterans who served in the 6888 during the war. The unit had already earned the European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, Women's Army Corps Service Medal, and World War II Victory Medal. The Congressional Gold Medal Act was introduced by Wisconsin Rep. Gwen Moore and garnered widespread bipartisan support in the House of Representatives, where it passed unanimously (via the U.S. House Committee on Financial Services). The medal was given to the Smithsonian Institution so it can be publicly viewed and used for research.

According to the National WWII Museum, in 2019, the 6888 was awarded the Meritorious Unit Commendation for Meritorious Service during Military Operations from February 15, 1945 to March 4, 1946. In April 2019, a documentary, "SixTripleEight" was made about the battalion, and it has since received many awards and commendations. The documentary told the full story of the 6888 for the first time, and though most of the 6888 had died by the time it was created, it still received support from many of their children and grandchildren.

Monuments to the 6888 and the Army Women's Hall of Fame

In addition to their many medals and recognitions, the 6888 also has several monuments dedicated in their honor. At the Massachusetts Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Agawam, Massachusetts, the 6888 has a monument honoring the lives of five veterans buried there: Wilma Lucas Jennings, Laura Bias King, Grace Lucas, Vivian Lucas Carter, and Yolanda Newport Jones.

In 2018, at Buffalo Soldier Military Park in Ft. Leavenworth, Kansas, the Buffalo Soldier Educational and Historical Committee dedicated a monument to the 6888 and Lt. Col. Adams. The monument is made of granite and has a large bronze bust of Adams on top of it. Adam's accomplishments and awards are also noted on the monument. The names of the original members of the 6888 are listed along the entire back panel, and on the front and side panels is information about the battalion's history and significance. The monument also has several pictures of the unit, both training at home and in action in Europe.

In March of 2016, the 6888 achieved one of the highest possible recognitions in the U.S. Army, when they were inducted into the Army Women's Hall of Fame. A surviving veteran of the 6888, Elsie Garris, attended the induction on behalf of the battalion (via the Army Women's Foundation).