What Humphrey Bogart's Last Movie Was Like Before He Died

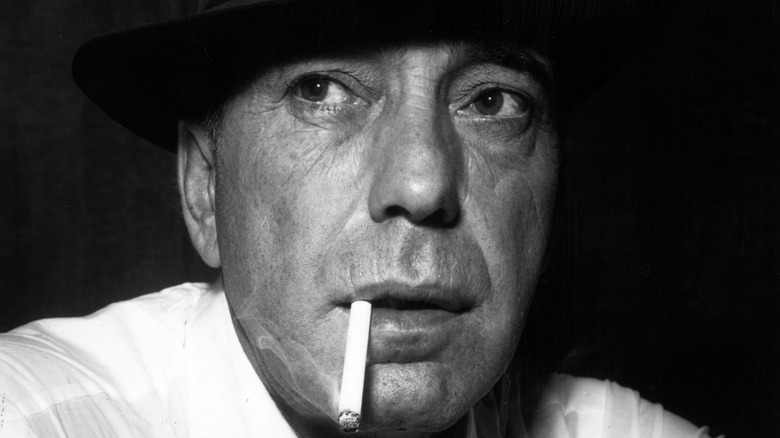

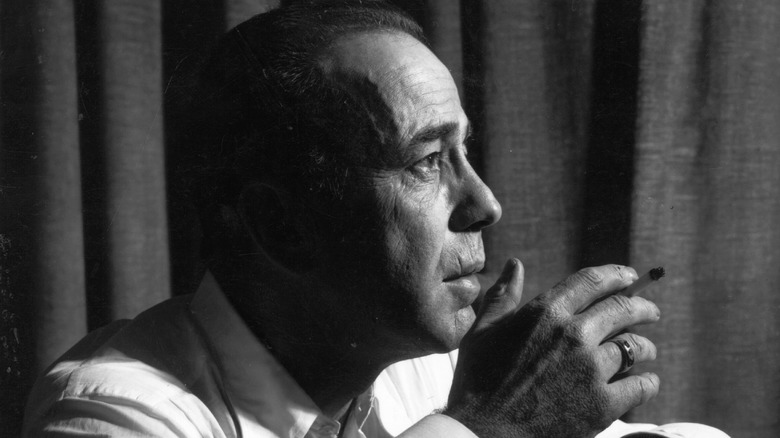

Few names are as evocative of the Golden Age of Hollywood as Humphrey Bogart's. Rated the No. 1 American screen legend (defined as a prominent actor who's film career began prior to 1950) in the AFI's "100 Years ...100 Stars" list, "Bogie" appeared across the silver screen from 1930 to 1956. A dedicated and talented actor, Bogart could show a lot of range, but it was his screen persona as the cynical tough guy with a deeply buried moral code that made him a star in gangster pictures, romantic dramas, and film noir.

Among the noirs featuring Bogart is "The Harder They Fall," described by Nina Metz for the Chicago Tribune as "something of a lost classic." It would prove to be Bogart's last noir, and indeed, his last film. It's a hard-hitting expose of organized crime's influence in the world of professional boxing, based on a novel by Budd Schulberg of "On The Waterfront" fame. No one knew at the time that it would be the finale to Bogart's career, but the first signs of an illness borne of hard living appeared during filming. "The Harder They Fall" premiered in 1956; Bogart died the next year of cancer. This is the story of what his final film was like.

An 'off night' with the true story

When writing "The Harder They Fall," Budd Schulberg took inspiration for his novel from various characters mixed up in the world of 20th-century professional boxing. According to the Irish Times, Humphrey Bogart's character, the broke and burnt-out sportswriter Eddie Willis, was modeled on boxing promoter Harold Conrad. A Brooklyn native, Conrad was a colorful and somewhat unscrupulous publicity man, as likely to rub elbows with notorious mobsters as the sports stars he managed — Muhammad Ali among them.

Bogart was Conrad's favorite actor. In his memoir, "Dear Muffo: 35 Years in the Fast Lane," he recalled how delighted he was to learn that Bogart was cast as a character based on him, how he fantasized about meeting his idol, and passing on a few pointers. The chance came at a restaurant one evening when Conrad happened upon the star. He introduced himself and said how proud he was to have Bogart playing him in a movie. Well into his cups, Bogart replied, "Why don't you go and f*** yourself." Conrad was devastated — until another encounter at another restaurant a few days later. A mutual friend heard about Conrad's story and summoned Bogart from another table to hear it. Now sober, Bogart laughed when told what he'd said. "I'm sorry, pal," he told Conrad. "You caught me on an off-night."

"If I hadn't got that squared away with Bogart," Conrad wrote, "I don't think I would ever have been the same."

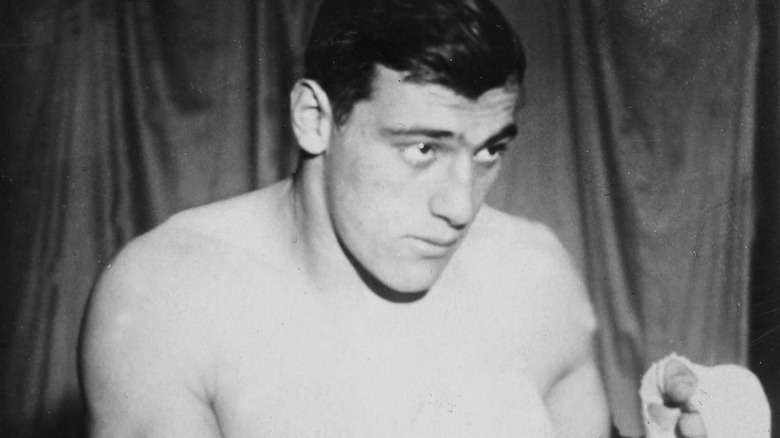

Primo Carnera's Unsuccessful Suit

The man behind Humphrey Bogart's character may have been delighted to have an on-screen alter ego, but Harold Conrad wasn't the only real-life figure fictionalized in "The Harder They Fall." Toro Moreno, the hapless boxer played by Mike Lane that Bogart is tasked with building up, was modeled on the "Ambling Alp" Primo Carnera. Like Moreno, Carnera's boxing career was, without his knowledge or involvement, a product of overblown press, fixed fights, and mob control, per Josh Sopiarz in Literature/Film Quarterly. Also like Moreno, the turning point in Carnera's career came when he entered into a real fight with opponent Max Baer that left Carnera severely injured. His mob-connected manager, having cleaned up betting against his own fighter, left him to lick his wounds. It was Baer who footed the bill for Carnera's stay in the hospital.

Unlike Conrad, Carnera did not take kindly to the adaptation. He didn't comment on Lane's performance, but he did bring a $1.5 million suit against Columbia Pictures and Budd Schulberg for invasion of privacy. Bogart was not named in the lawsuit and left no public comment about its development. But Carnera's boxing career was still within living memory in 1956; before it became known as Bogart's final film, reviewers at the time noted the connection between the movie and the ex-heavyweight, according to the AFI. Unfortunately for Carnera, he lost his suit. A judge concluded that, as a public figure, he had waived his rights to privacy.

A Long Time Coming

Many projects see several years pass from being announced as a film to becoming one, and "The Harder They Fall" was no exception. The AFI has tracked its path from a novel published in 1947 to an RKO property that same year, where it was meant to star Robert Mitchum and Joseph Cotton. But fate had other ideas; RKO's mercurial owner Howard Hughes passed the rights to the book to Warner Bros., and eventually, Columbia Pictures got hold of the book and set a 1955 production date.

"The Harder They Fall" first came to Humphrey Bogart's attention when it was in the hands of Warner Bros., according to Turner Classic Movies. Warner Bros. was the studio where Bogart made his name. At the time of the book's publication, he just a year into a new contract, described by The New York Times as the longest-term agreement for an actor with a studio on record. Eddie Muller of Turner Classic Movies has said that Bogart saw "The Harder They Fall" as an ideal follow-up for himself and his friend and co-star Edward G. Robinson after they enjoyed success with the noir film "Key Largo" in 1948. But Bogart's say at Warners proved less longeval than the New York Times predicted. By the time he had the chance to appear in "The Harder They Fall" in 1955, neither Bogart nor the property were at Warner Bros. anymore, and Robinson did not end up cast alongside him.

Soft Spot At Columbia

The man in charge of Columbia Pictures in the 1950s was Harry Cohn. Even among his fellow moguls in Hollywood's golden age, Cohn had a reputation for tyranny. In his biography of Humphrey Bogart, "Bogart: The Search of My Father," the actor's son Stephen Bogart described Cohn as "the most feared and hated man in Hollywood ... known for his vulgarity and ruthlessness and such antics as spying on his employees with secret microphones and informers. He was a complex man who trumpeted his evil deeds and kept his acts of kindness secret."

For all that fearsome reputation, Stephen Bogart suspects that Cohn had a soft spot for his father. Columbia acted as the distributor for Bogart's production company Santana and put "The Harder They Fall" into production after they got hold of the rights. Cohn's fondness for Bogart showed itself away from the studio too. When Bogart became too sick to work after "The Harder They Fall" wrapped, Cohn would call him up, encouraging him to get well so he could go back to work in a part perfect for him in a film adaptation of C. S. Forester's novel "The Good Shepherd." Cohn knew Bogart wasn't long for the world, but he wanted to help lift his spirits.

Farewell, Santana

Between his years at Warner Bros. and making "The Harder They Fall" for Columbia, Humphrey Bogart went into the picture business for himself. According to his estate's official website, he launched Santana Productions (named for his yacht) in 1948 as a reaction against the status quo in Hollywood, specifically the studio system that kept actors bound by contract to one studio. This business of stars having their own companies was unusual for the time and taken by Jack L. Warner as a threat to the studio system. In "Bogart: In Search of My Father," Stephen Bogart claims that Warner was so upset over the development that he took it out on Bogart's agent Sam Jaffe.

Santana released seven films between 1949 and 1953, all but one of them distributed through Columbia Pictures. The company was still active when Bogart signed on to "The Harder They Fall" as a Columbia production. But the deterioration of his health after shooting precluded any return to work, whether it was for Columbia or himself. When Bogart's condition reached the point of surgery, biographer Allen Eyles reports that he needed to sell his company to generate some income. The buyer turned out to be Harry Cohn and Columbia Pictures, at the price of $1 million.

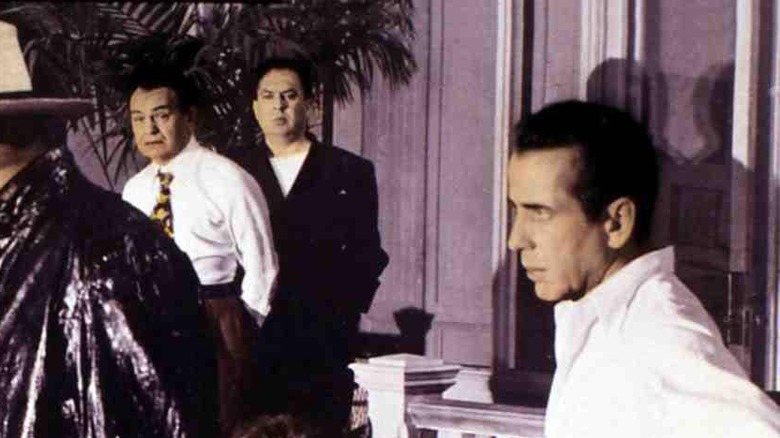

Bogie's Co-Star Liked Him

Cast alongside Humphrey Bogart's Eddie was Rod Steiger as Nick Benko, the corrupt promoter and fight fixer. Throughout his career, Steiger proved no stranger to noir and crime drama and, like Bogart, developed a persona as a "Mafia heavy or near-psychopath," as friend Tom Hutchinson put it in his memoir of the actor, "Rod Steiger: Memoirs of a Friendship." "The Harder They Fall" was an early effort by Steiger in such a role, and in the movies; it was only his seventh film.

Steiger had a lot of respect for Bogart and got along with him well during filming. The interview collection, "25 Years of Celebrity Interviews," by David Fantle and Tom Johnson, includes Steiger's recollections on the production. Steiger said that, unlike some stars, Bogart never tried to work his way into close-ups or his fellow actors out of shot. Always the professional, he turned up at 9 in the morning, did his work, and headed out by 6 p.m. It was a surprise for Steiger to come across Bogart on the lot after quitting time one day. The elder actor explained that he needed to do a few retakes due to watery eyes. It was only after Bogart's death that Steiger realized those watery eyes came from the pain of battling cancer.

But Bogie Didn't Like The Method

They may have both made their names as tough guys in the movies, but Humphrey Bogart and Rod Steiger were very different in their approach to acting. Steiger was among a rising generation of method actors who felt it necessary to plumb and experience the inner life of a character. Bogart, who came up through the New York stage, as per Biography, considered this unnecessary. According to a biography by Alan Frank, Bogart found the lack of diction and precision with dialogue distracting to his own performance. "Words are important," he complained to his friend Jerry Wald. "This scratch-your-a**-and-mumble school of acting doesn't please me."

According to Robert Osborne of Turner Classic Movies, Bogart distinguished between his professional frustrations and personal feelings toward Steiger; he liked Steiger as a human being, just not as a fellow actor. And Bogart did eventually find a way to work around "the Method." Jeffery C. Meyers' "Bogart: A Life in Hollywood" quotes the explanation given to Nunnally Johnson of Bogart's technique: patience. Bogart gave the example of the line, "Hey, you, come here." Steiger would stutter and stretch the line out with repetition and filler sounds and phrases. "But if you wait," said Bogart, "eventually he'll get around to saying, 'Hey, you, come here.' And you can go ahead with it."

Humphrey Bogart Was Dying While Filming

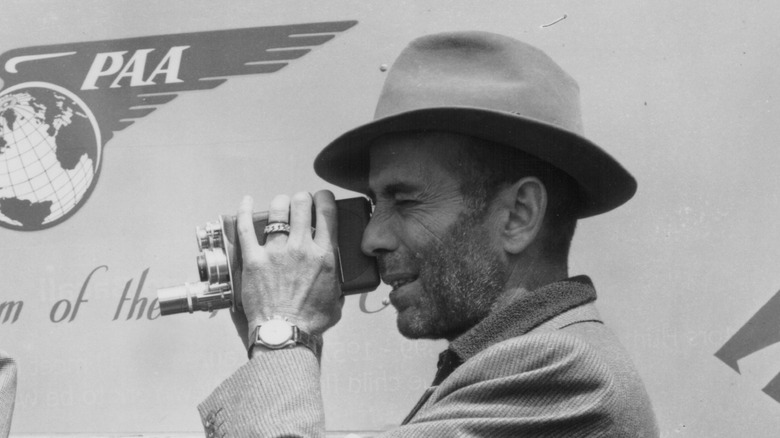

In Allan Frank's biography of Humphrey Bogart, he notes that the actor was often tired during the filming of "The Harder They Fall" in 1955, plagued by a persistent cough. He was sick, but it wasn't until the following year, just before the film's premiere that the diagnosis was made, notes Robert Osborne for Turner Classic Movies. A lifelong smoker and a hard drinker, Humphrey Bogart was dying of esophageal cancer. He checked into a hospital for surgery, but the damage was too severe. His health continued to decline until his death, and he never worked again.

Undiagnosed during the filming of "The Harder They Fall," Bogart didn't let any of the symptoms he was suffering interfere with work. Tired as he might have been, persistent as his cough was, he continued to show up on time, hit his marks, deliver his cues, and head home. Those teary-eyed retakes of Rod Steiger's memory were the closest Bogart's condition came to holding up production on the film.

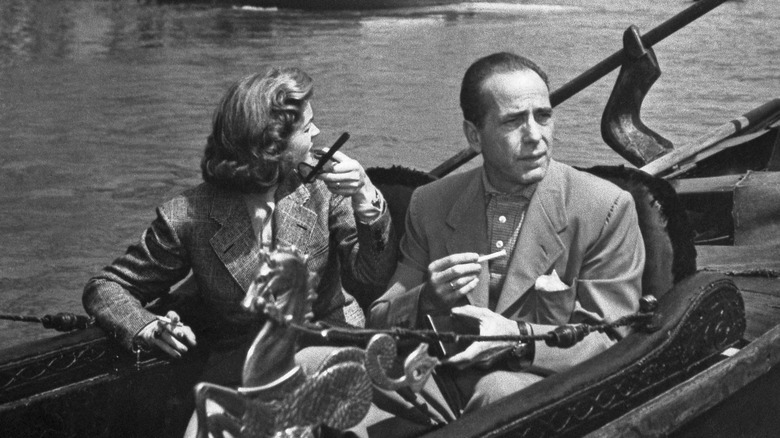

Bogart Hoped For More

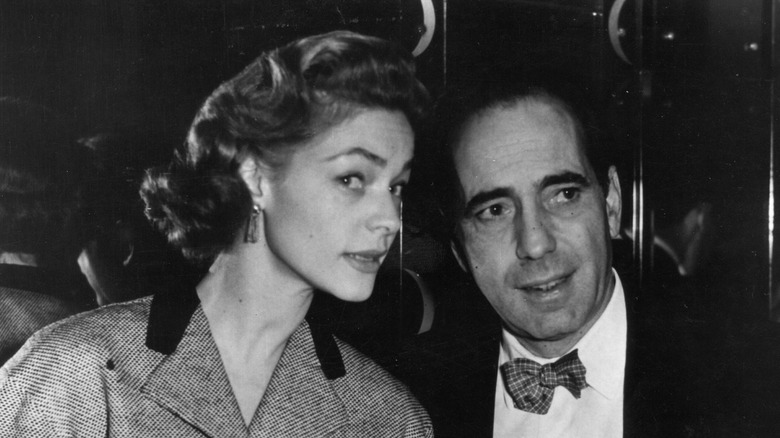

Humphrey Bogart had no reason after filming wrapped on "The Harder They Fall" to think he wouldn't have more films ahead of him. He seemed poised to stay busy as ever going into the movie's premiere and the working year for 1956. Allen Eyles has documented several of the projects Bogart had in the works: a comedy with wife Lauren Bacall back at Warner Bros. titled "Melville Goodwin USA," adaptations of "The Man Who Would be King" and "Moby Dick" for John Huston, the sea drama "The Good Shepherd," and even the offer of a Western from Columbia and Harry Cohn. Some of these were projects Bogart was ambivalent about or rejected before he fell ill (no Westerns for Bogie), but "Meville" and "The Good Shepherd" were heading for production in 1956.

But the cough and pain that had been a minor inconvenience on "The Harder They Fall" progressed rapidly, leading to Bogart's diagnosis and surgery. Costume tests had already been shot for "Melville Goodwin USA," but the comedy was postponed to allow for treatment. After the surgery, however, Bogart was forced to withdraw from "Meville" altogether; despite acting as if he expected to recover, he was too sick to work. "The Good Shepherd" remained nominally in development at Columbia, and it became the project Cohn used to help keep Bogart in good cheer during his decline.

Vocal Funny Business

A star with an undiagnosed illness that ultimately kills him, reminiscences by co-stars who saw only hints of how sick the screen legend was: It's the sort of Hollywood scenario that inspires myths and urban legends. The fact that Humphrey Bogart's voice is sometimes a bit on the husky side in "The Harder They Fall" helped create such a rumor. In his book on Bogart for the Pictorial Treasury of Film Stars series, Alan G. Barbour recounts the claim that it was necessary for impressionist Paul Frees to redub some of Bogart's dialogue.

Frees, who was a straight actor as well as a comedian and impressionist, does make a brief appearance in "The Harder They Fall" as a priest. That could well have contributed to the rumors. But it remains just that — a rumor. There is no official confirmation from Columbia nor any verified source to the claim that Humphrey Bogart did not complete all his work for "The Harder They Fall," redubbing included.

Two Endings

The ending to Humphrey Bogart's career as an actor has itself two different endings. Eddie Muller of Turner Classic Movies explains what happened: Author Budd Schulberg and director Mark Robson were divided on how to wrap up "The Harder They Fall." Schulberg preferred an ending where the Bogart character urges Congress to investigate and clean up the influence of organized crime in boxing. Robson wanted Bogart to denounce the entire sport and advocate for outlawing it. The director personally found boxing a revolting pastime and made no bones about it in his approach to the film.

Schulberg, on the other hand, was an avid boxing fan who only wanted to see its act cleaned up. He felt that Robson's approach lacked compassion, a serious enough affront that the friendship between the two men fell apart. Columbia ultimately sided with Schulberg, making Bogart's final screen scene into the milder call for regulation over abolition. Both endings have appeared before audiences; according to All Movie, Robson's preference appeared on early video releases, while Schulberg's ending was aired on TV.

If Bogart had a preference, he left it unsaid; he had his own, losing battle to fight. But according to biographer Allen Eyles, Bogart happily took in a championship match featuring Sugar Ray Robinson shortly before his death, so it may be safe to infer he was of Shulberg's mind about boxing.