The Time The CIA Overthrew The Government In Guatemala

The CIA has a much maligned reputation in 2022. Between revelations about secret torture files, unauthorized spying on American citizens, secret mind control experiments, and their shady involvement in the JFK assassination, the CIA has seemingly been associated with an endless stream of scandals. President Harry S. Truman originally created the CIA in September 1947 as part of the National Security Act, in order to coordinate intelligence efforts among all U.S. government agencies (per the Truman Library). The CIA was the final successor to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a secret intelligence and covert operations agency that functioned in Europe during WWII.

The agency, however, quickly morphed from just intelligence gathering and espionage to full blown participation in revolutions and regime changes. In 1953, the CIA orchestrated the overthrow of the Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, and in 1960 they aided Congolese militants in the execution of Patrice Lumumba (via ForeignPolicy.org).

Sandwiched between these coups was the forced regime change in Guatemala, where in 1954, the CIA played a pivotal role in the ousting of President Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán. The American role in the bloody coup was suppressed from American audiences for years, and even today the full story is probably not completely known. A depressing and embarrassing moment in American foreign policy, this is the time the CIA overthrew the Guatemalan government.

The 1945 Guatemalan Revolution

A decade before the coup, and before the CIA even existed as an organization, the 1945 Guatemalan Revolution occurred. According to Walter LaFeber in "Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America," in the 1930s and early 1940s, the dictator Jorge Ubico ruled Guatemala through a corrupt and repressive system. Elections were rigged and there was little done for the social and economic welfare of the majority of the nation's impoverished citizens. The revolution was led by college students and younger army officers, and they immediately held free elections which brought former teacher Juan José Arévalo to the presidency. Arévalo considered himself a "spiritual socialist," and he considered both Marxism and capitalism to be flawed.

In November 1950, Arévalo's term expired, and Guatemalans elected Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán as their new president. Richard H. Immerman describes in "The CIA in Guatemala," how Árbenz articulated a new plan for Guatemala that focused on social justice and agrarian reform. Árbenz wanted to completely change the unequal economic relationship between wealthy large-scale landowners and the impoverished peasantry. Árbenz sought to create a system that could reclaim the land through an industrial labor force that would focus on growing a variety of staple foods. The Guatemalan economy was almost entirely oriented towards just bananas at that point, which made the country reliant on foreign imports, and kept wages low for workers and profits high for plantation owners.

United Fruit and the 1952 agrarian land reform law

In 1952, as part of its agrarian reforms, the Árbenz government passed a radical and wide-ranging land reform law. In "Overthrow: America's Century of Regime Change," Stephen Kinzer writes that the law allowed the government to seize large swathes of uncultivated land and compensate the owners according to the declared taxable value of the land. This worried the massive United Fruit Company (UFCO), which had 85% of their land lying fallow, and had already achieved an undesirable reputation in Guatemala. In a clear example of "Yankee Imperialism," UFCO had capitalized massively in Guatemala during the previous half-century. The company's value had jumped from $20 million in 1890 to $150 million in 1920, and by 1950 it was averaging roughly twice the annual revenue of the entire Guatemalan government (per the "CIA in Guatemala"). Guatemala alone made up a quarter of UFCO's profits, but the peasantry saw none of the prosperity.

According to "Overthrow," under the terms of the reform law, the Árbenz government confiscated 234,000 acres of uncultivated land at UFCO's Tiquisate plantation in Guatemala and offered them the declared taxable value of $1.185 million. UFCO, however, had been severely undervaluing the true taxable amount of the land for decades, and they balked at the low figure. They countered with a demand for $19 million instead, which the Guatemalan government rejected.

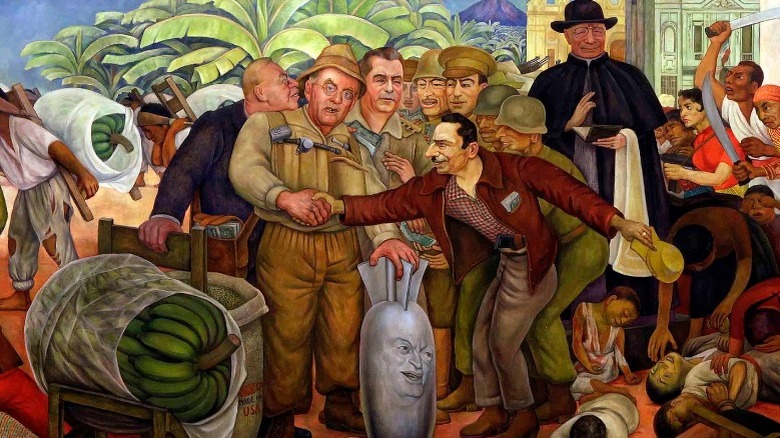

Tommy 'the Cork' Corcoran and El Pulpo

In their book "Bitter Fruit," Stephen Kinzer and Stephen Schlesinger argue that in the 1940s, the United Fruit Company (UFCO) started working to repair their much maligned public reputation. UFCO hired P.R. consultant Edward Bernays to change the public image of the company, which by that point had become known as "el pulpo," or "the octopus," because its tentacles wrapped all around Central America. Not only did Bernays work to make UFCO appear in a positive light, but he also worked to discredit the Árbenz government as full of communist infiltrators who would, obviously, have anti-American attitudes. The 1953 land reform laws were the last straw for Bernays, who used that as proof of the communist intentions of the government.

Bernays was also working to get the U.S. government on his side in his campaign against Árbenz. He used lobbyist and lawyer Tommy "the Cork" Corcoran as his intermediary. Corcoran (above right) had numerous connections to government and CIA officials, and he actually served as the lawyer to a secret CIA airline. In early 1953, Corcoran started directly lobbying CIA officials to act against the Árbenz government. UFCO also hired ex-Marine John Clements and former Truman-era assistant secretary of state for Latin America, Spruille Braden, as P.R. representatives, too.

United Fruit Company, the Eisenhower Administration, and the CIA

In addition to the lobbying efforts of Bernays and Corcoran, UFCO and the CIA already had a significant amount of personal connections. According to "Bitter Fruit," the connections between the two ran deep. The secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, had previously done legal work that involved UFCO which had made him a good chunk of money. His brother and the director of the CIA, Allen Dulles, had also previously worked for the same law firm and had other more discrete connections with UFCO.

Former head of the CIA and current Undersecretary of State, Walter Bedell Smith, was inquiring about a possible job as president of UFCO with P.R. man Corcoran. UFCO P.R. director Ed Whitman's wife Anne was Dwight D. Eisenhower's personal secretary. "Inevitable Revolutions" notes that Whitman had previously made an anti-communist film, "Why the Kremlin Hates Bananas," that even featured UFCO as a protagonist.

Operation Success and making Árbenz a communist

The Árbenz government's many reform programs had started to convince many in Washington that the regime was turning communist (per "Inevitable Revolutions"). Odd Arne Westad argues in "the Global Cold War" that by early 1953, Árbenz's increasing cooperation with the Guatemalan Communist Party was seriously concerning to the United States. The CIA was also warning about general unrest throughout Latin America, which combined to heighten fears at the White House. That summer, Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered preparations for a coup to overthrow the Árbenz government and replace it with one absent of communist influence.

The planning for the coup was called Operation Success and was spearheaded by CIA director Allen Dulles. It relied on several interlocking parts, as detailed by John Prados in "Safe for Democracy." The coup assumed that Guatemalan armed forces were weak and pliable, but that they could act as the ultimate determiner of a Guatemalan coup. The CIA planned a vast propaganda campaign to turn the armed forces and civilians against the Árbenz government. Simultaneously, the CIA would organize a new "revolutionary" government that would march into Guatemala and seize control in a frenzied coup. The CIA would provide logistical and covert support and work to get the armed forces behind the new "revolutionary" government. The CIA needed all of the parts to come together, because if just one major aspect did not succeed, the coup would be in serious jeopardy. Even worse, the CIA's role might be discovered.

The secret CIA armies in Nicaragua and Honduras

As part of their plan to create a "revolutionary" government and help it infiltrate Guatemala, first, the CIA needed to create the army that was supposed to lead the invasion. "Bitter Fruit," argues that the CIA's first two choices did not work out, and they went with their third option, former Guatemalan army officer Carlos Castillo Armas. Armas had previously served during the Arévalo presidency, but left in 1949 and had led a failed rebellion against the government the following year. One newspaper correspondent at the time suggested part of the reason the CIA picked Armas was because he was dumb and therefore easy to manipulate. Armas was already looking at ways to strike back against the Guatemalan government. He had previously even raised $60,000 from Dominican Republic dictator Rafael Trujillo, but nothing came of the plans.

To train the new revolutionary forces, the CIA created training sites in Honduras and Nicaragua (per "The CIA in Guatemala"). In Nicaragua, the sites were located on an estate known as El Tamarindo, which was owned by Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza García, friend to the U.S. government. The U.S. sent tons of guns and ammunition to Tamarindo, and they also created an air force for Armas in both Honduras and Nicaragua. They even sent tanks and strategic bombers (which never made it), along with an assortment of mortars, flamethrowers, and other heavy material.

CIA Airlines and Chinese pilots

The air force that the CIA used to aid the Carlos Castillo Armas revolutionary armies in Honduras and Nicaragua was actually a secret CIA front known as Civil Air Transport (CAT). According to "Safe for Democracy," U.S. ambassador to neighboring Honduras, Whiting Willauer, was also a senior manager at the CIA who owned CAT, and he was getting briefings from the CIA on how to assist the Armas' revolutionary army. Willauer worked with the Honduran government to keep them apprised of the situation, and he eventually created a force of roughly a dozen aircraft.

At the time, the CIA was also training fighter pilots led by Chiang Kai-Shek, and one source claimed that some of the pilots working the Guatemala operation were actually Chinese (per "Safe for Democracy"). Willauer became so intimately involved in the operation that CIA officials started to worry he had too much influence. By this point, planning for the coup was in full swing and the secret armies were being equipped by rapid deliveries from the CIA.

The secret CIA radio station in Florida

As part of their plan to inundate the Guatemalan public and armed forces with anti-Árbenz propaganda, the CIA created the fictitious "Voice of Liberation" radio station to broadcast messages into Guatemala. In his history of the CIA's role in the coup, Nick Cullather details the radio station, codenamed Sherwood. The radio station became active in Guatemala in early May 1954 and called itself "La Voz de la Liberación," and it contained a mix of popular music, comedy, and CIA-created anti-government propaganda. The announcers alleged they were guerillas living deep in the jungle and urged resistance of the government and of communism more broadly. It also started to name the Armas revolutionary armies and called them forces of liberation.

In reality, as Cullather points out, the broadcasts were not coming from inside Guatemala, but were actually being broadcast from the Sherwood station in neighboring Honduras. The tapes themselves were recorded in Miami and sent to Honduras onboard Pan American Airways flights. Cullather also notes that during two crucial weeks of the operation, the official Guatemalan government radio station went offline for upgrades, which left the "Voice of Liberation" with a "virtual monopoly" over the airwaves.

The big spark, the Alfhem weapons delivery

In January 1954, while planning for the coup was in high gear, the Árbenz government publicly accused the U.S. government of attempting to create a "counterrevolutionary plot" to overthrow them (per Tim Weiner in "Legacy of Ashes"). Details of the coup, based on leaked CIA cables that a CIA officer had mistakenly left behind in a hotel room, soon splashed across the pages of all the major newspapers. CIA manager Tracy Barnes soon authorized a scheme to plant Soviet bloc weapons on the Nicaraguan coast and attribute them to Guatemala, and started inventing stories about death squads roaming around with Soviet advisors. The scheme and planted stories proved unsuccessful.

However, a few months later in late May, Weiner writes that the CIA got their propaganda coup, and they did not even need to plant it. The Árbenz government had lost its ability to purchase weapons after the U.S. had enacted a weapons embargo against them years earlier, and they were desperate to find a way to arm their poorly equipped army. In his desperation, Árbenz made a deal with Czechoslovakia to send weapons and ammunition in exchange for almost $5 million. The weapons when they arrived were outdated and mainly useless, but the CIA had discovered the shipment used it to their full advantage. They immediately charged that the Árbenz government was in league with the Soviets and were part of a massive Soviet-led conspiracy against the West.

Operation Success commences

Days after the news of the Alfhem weapons delivery became public, the wheels of Operation Success started to turn in motion. According to "Bitter Fruit," air force Col. Mendoza Azurdia defected on June 4, and the "Voice of Liberation" kicked into high gear. On June 15, Eisenhower had his last official meeting on the coup, where he told his guests, which included among others both of the Dulles brothers, "I want you all to be damn good and sure you succeed ... if it fails the flag of the United States fails." On June 8, amid the confusion, the Árbenz government suspended civil liberties in Guatemala and started arresting suspected coup plotters, some of whom were tortured (per Cullather).

According to "Bitter Fruit, on June 16, Carlos Castillo Armas finally left his hideout in Nicaragua and traveled to Honduras to meet his army for the first time. On June 18, he led his army west six miles into Guatemala, where they promptly parked and waited for further instructions. The CIA started to put their air force to use by dropping leaflets on Guatemala City to rouse the townspeople. In order to sow panic, one pilot dropped a hand grenade and dynamite stick on a fuel tanker, which caused only a minor explosion but raised big fears on the ground.

The coup faces a setback

Events quickly showed that the coup was not going to be as easy a feat as plotters had hoped. Though the grenade and minor explosions were successful, they inflicted only minor damage in limited areas. To make matters worse, one pilot crash landed in Mexico and had to explain his situation, and two more were hit by fire from small arms on the ground and put out of commission (per "Bitter Fruit"). Carlos Castillo Armas' forces that took action faced immediate resistance from the Guatemalan army and had to turn back. According to "Legacy of Ashes," Armas' forces made three separate raids and all of them failed; half of his force was gone within three days of the invasion. "Inevitable Revolutions" notes that not only did the invasion stall, the planned uprising of civilians did not happen and the Guatemalan army remained loyal to the government instead of defecting.

"Legacy of Ashes" argues that by June 22, five days into the invasion, the planners realized the coup was at a crossroads. The Ambassador to Guatemala had been calling for days asking for more planes to bomb the capital to turn the city against Árbenz. The afternoon of the 22, CIA director Dulles and two other pleaded with Eisenhower to allow more planes to bomb the city. Dulles told him that with more planes the chance of success was maybe a paltry 20%, but without them the coup had no chance.

The Springfjord incident and the final bombing campaign

Under pressure from Dulles and fearing the coup would be lost, Eisenhower relented and authorized additional airstrikes. The airstrikes were less effective than anticipated, but it ended up not mattering in the end. According to "Secret History," most of the bombs were of WWII vintage and ended up not exploding when they were dropped, and they failed to prevent the buildup of the Guatemalan army opposing the Armas invasion. Carlos Castillo Armas kept demanding airstrikes to cover his troops small skirmishes and engagements, but they often proved futile and unhelpful.

"Safe for Democracy," highlights the one significant effect of the airstrikes, which was the blowing up of a British merchant ship, the "Springfjord," located in a Guatemalan harbor. Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza, who had allowed the CIA to construct camps on his estate at El Tamarindo, thought the Springfjord was full of gasoline that was going to be used to fuel a counter invasion of Nicaragua. He ordered CIA agents to bomb the vessel, and they in turned ordered their pilots to do so. The Springfjord was hit by a 500 pound bomb and quickly sunk, but luckily no one was injured. Washington profusely apologized to the British and the CIA reimbursed Lloyd's of London $1.5 million for insurance.

Operation Success succeeds

A combination of the air, ground, and propaganda campaigns together finally led to the resignation of Árbenz. As detailed in "Overthrow," during the final bombing campaign, Árbenz had sent his foreign minister Guillermo Toriello to New York to urge the United Nation's security council to start an investigation of the coup. However, the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Henry Cabot Lodge, successfully got the council to vote against doing so. Toriello tried to message CIA director Dulles, but he was ignored.

In Guatemala, it became apparent that the "Voice of Liberation" radio had finally succeeded in convincing the Guatemalan people about the Armas invasion and had turned public opinion. On June 27, realizing that he had lost the support of the people and his army, Árbenz decided to surrender. According to Kinzer, that afternoon the U.S. Ambassador to Guatemala John Peurifoy convinced army commanders to depose Árbenz, and they did so after calling him in for a meeting. They promised to never work with the Armas revolutionary army and allowed him a final 15 minute address of the country. In his farewell, Árbenz explicitly blamed UFCO and the U.S. for their collaboration, and suggested life under Carlos Castillo Armas would result in "20 years of fascist bloody tyranny."

Was Operation Success really a success?

The new military Junta, led by Col. Carlos Enrique Díaz, was quickly dissolved (per Kinzer in "Overthrow"). U.S. Ambassador John Peurifoy had heard Árbenz's final broadcast and was enraged. He sent two CIA operatives to confront Díaz and inform him who was really in charge of the situation, the Americans. Peurifoy authorized one final bombing of the Guatemalan capital, which along with a gun pointed at him, finally convinced Díaz to relent the presidency. Eventually, Carlos Castillo Armas took over in July and formed a ruling military junta.

The Armas junta immediately set about consolidating their power in Guatemala. Opposition political parties were immediately banned, the land reform program was abolished, political opponents found themselves murdered or jailed, and the United Fruit Company got all of their appropriated land back (per "The Cold War"). In 1957, just three years later, Armas was himself assassinated in his own presidential palace by a member of his own guard, Romeo Vásquez Sánchez, who immediately committed suicide himself (per "Surprise, Kill, Vanish").

That the CIA conceived and sponsored the 1954 Guatemalan coup is a forever dark stain in the history of American foreign policy. A democratically elected leader was removed from power due to false accusations about his relationship with the communist party, and the country of Guatemala was put on a decidedly less democratic path in the aftermath. This was the time the CIA overthrew the Guatemalan government.