The Peshtigo Fire: The Deadliest Wildfire In History

Although the Peshtigo Fire is the deadliest fire to have ever occurred in the United States, few know it by name. And while many know of the Great Chicago Fire, they don't realize that the Peshtigo Fire actually occurred on the exact same day.

The Peshtigo Fire was practically forgotten in its immediate aftermath as it was overshadowed by the Great Chicago Fire. This wasn't on purpose, given the inability of news to travel about the Peshtigo Fire, but it certainly had a lasting impact on the memory of the United States, per History. And as more and more devastating wildfires are occurring in the United States every year, it's worth looking back on the worst fire in American history. As with some of the most severe climate catastrophes, the Peshtigo Fire was caused by a perfect storm of variables that may have been enhanced by a particularly bad drought.

The devastation of the Peshtigo Fire is not only unmatched, but the entire scope of the devastation is also unknown. The number of casualties is believed to be grossly underestimated, and without accurate census data, it's impossible to know exactly how many people lost their lives in the deadliest firestorm in the history of the United States.

A dry year

1871 was an incredibly dry year for Wisconsin and Michigan. In addition to a lack of snow during the winter months, Door County Pulse writes that there was a drought in the region during the summer. As a result, many swamps dried out, and sporadic fires started occurring. Even Reverend Peter Pernin, one of the witnesses of the Great Peshtigo Fire, noted the unusual dryness of the year. According to "Watertown Fire Department, 1857-2007" by Ken Riedl, the Rock River noticeably dried up, affecting even the various mills that required water from the river to function.

A number of factors helped fuel this inferno. Fire Engineering writes that railroad companies would also clear vegetation from their tracks and leave everything behind in piles that were sometimes set on fire from a spark from a passing steam locomotive. Many towns, like Peshtigo, were built entirely with wood, everything from the buildings to the sidewalks. And because much of the industry in the area worked with wood, there were also many large piles of bark and sawdust. Unfortunately, this would all end up acting as kindling for the inevitable flames.

Another factor in the increased number of fires was the usage of slash-and-burn agriculture, which involved cutting down and burning vegetation to make way for farmland. Although these fires were intended to be controlled burns, as in the case of the Peshtigo Fire, sometimes fire can get out of control very quickly.

Winds from the south

On October 8, 1871, a large cold front came in from the Great Plains. According to Minnesota Public Radio, because of the huge difference of 40 degrees in temperature around the cold front, this resulted in incredibly strong winds with speeds up to 32 mph. Any other time, this may not have necessarily had the destructive power it subsequently did, but the dry weather and the controlled burns at the time came together with the winds to create conditions for a perfect firestorm. However, Damn Interesting notes that among this variety of factors, to this day, no one is sure what exactly was the main cause of the Peshtigo Fire.

As a result, Earth Magazine writes that all the small fires that were burning at the time were whipped into a frenzy as they grew and converged into a single fire. Although many of the people in the region had thought nothing of all the smoke in the air, around 10 p.m. that night, Peshtigo Fire Museum documents that the flames became impossible to ignore. Amidst a muted rumbling sound, similar to a freight train, a wall of fire burst through the forest and towards the town of Peshtigo, Wisconsin.

A tornado of fire

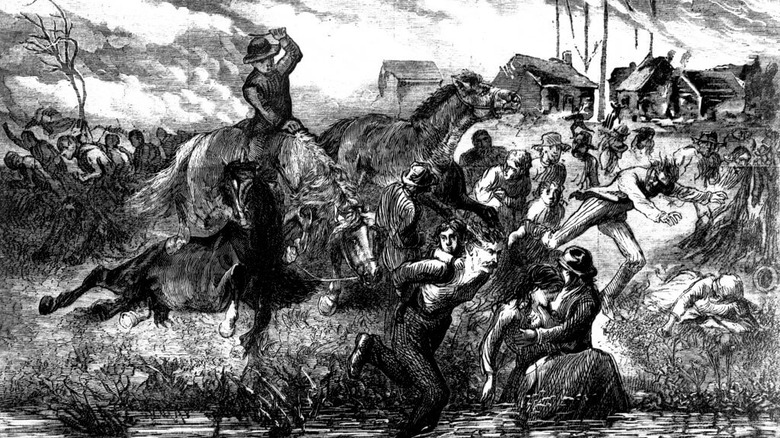

With the merging of the small fires and the influence of the wind, the fire became a wall of flames that raced onto the town of Peshtigo. And as the winds changed direction, Fire Engineering writes that the inferno became a tornado of fire that engulfed the town, utterly destroying it within an hour.

People tried to flee, but the strong winds blew them to the ground as the smoke blinded them. According to the Peshtigo Fire Museum, the temperature of the air rose to such a degree that people's lungs were burned as they tried to breathe. The flames and sparks whipping through the air also set peoples' hair and clothes on fire.

Earth Magazine reports that based on the fact that there were areas of sand that turned to glass, the fire is estimated to have reached temperatures of over 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit and it's estimated that the winds traveled at almost 100 mph. Many survivors described the flames as moving "faster than it takes to write these words."

The fire burned with such ferociousness that it created its own weather system.

Meanwhile, all the Peshtigo Fire Company had was "a single horse-drawn steam pumper to protect houses and the small factories near the river," with no other form of organized fire protection. As a result, they were helpless against the blaze that assaulted the town.

Running to the river

Although it was next to impossible to outrun the flames, many fled to the Peshtigo River. According to the Peshtigo Fire Museum, although the water was cold and many didn't know how to swim, they decided that it was better to drown than to be burned alive.

At the very center of the fire, the vortex was surprisingly clear and free of smoke, and as the fire tornado traveled through the town, it ended up traveling over the river where people were seeking refuge. Earth Magazine writes that the air temperature reached over 500 degrees Fahrenheit and people had to repeatedly dip themselves in the water to put out the flames that kept erupting in their hair.

Unfortunately, not everyone was able to survive the entire ordeal. Some of those who survived the fire tornado ended up dying from hypothermia in the river as they were forced to remain in the water for hours. One survivor, Father Pernin, reportedly spent over five hours in the river. According to The History Engine, some people also managed to survive by seeking refuge in wells.

Over 1.5 million acres

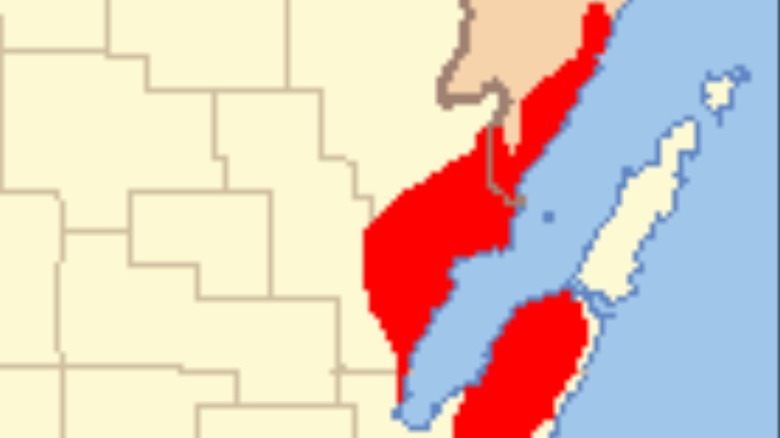

The firestorm burned along Green Bay to the Menominee River through several towns. By the time the fire reached Lake Michigan, the storm winds had started to slow down, and the coming rains finally helped put out the flames. It was the weather that brought in the intense winds fanning the flames of the Peshtigo Fire that, luckily, also ended up being responsible for quelling the fire as well. According to Fire Engineering, rain clouds came in by the following day and helped put out the fire near Lake Michigan.

In total, the fire burned through more than 1.5 million acres, or over 2,000 square miles, of land and forest in Wisconsin and even reached parts of Michigan by Green Bay. Roaring through 16 towns, though Peshtigo received some of the most severe damage, some estimate that the Peshtigo Fire may have actually burned as much as 3.7 million acres.

According to the National Weather Service, the Peshtigo Fire did about $169 million worth of damage, which was roughly the same amount of monetary damage done by the Chicago Fire.

Thousands dead

Despite the fact that the Peshtigo Fire only burned for less than 48 hours, it did so much damage that it's considered to be the deadliest wildfire in the recorded history of the United States. The fire is named the Peshtigo Fire because of the 800 people that died in Peshtigo, Wisconsin -– half of the town's population according to Fire Engineering -– but it's estimated at least 2,000 people were killed as a result of the fire. The exact number of casualties is unfortunately unknown and is likely to be much higher due to the populations of Indigenous people in the area as well as the large numbers of workers that lived in boarding houses and camps in the area.

Many of the bodies that were found were burned to the bone and beyond recognition, leaving no method to identify them. Wildfire Today writes that over 350 people were buried in a mass grave. Others were found having suffocated to death, with few burns on their body. Door County Plus reports that bodies continued to be found up to a month after the fire.

And humans were not the only casualties of the Peshtigo Fire. Most animals living in the forest and the livestock owned by people, didn't survive. "Birds were seen trying to escape but burned in midair or sucked back into the vortex," writes the Peshtigo Fire Museum.

Blinded by the smoke

Those who managed to survive the Peshtigo Fire were left badly burned and barely able to breathe amidst the hot air left in the aftermath. And according to the Peshtigo Fire Museum, many were also temporarily blinded by the smoke, which hung like a cloud over the town of Peshtigo even after the fire had moved along.

Although, for many, the inability to see was only temporary, it made it incredibly difficult to find survivors. Father Pernin, one of the survivors of the fire, reportedly started performing his priestly duties and consoling those who were dying even before his eyesight returned.

According to the Wisconsin Historical Society, at least 1,500 people were left severely injured, and at least 3,000 people were rendered houseless as a result of the Peshtigo Fire.

The smoke continued to hang in the air for several days, making it difficult for even sunlight to penetrate through.

A day of fires

The following day, news of a fire in the Midwest was all over the headlines of American newspapers. But these headlines weren't about the Peshtigo Fire. Instead, all eyes were on Chicago. The Great Chicago Fire had burned the very same day as the Peshtigo Fire.

According to Damn Interesting, although the Great Chicago Fire didn't have as high of a casualty rate as the Peshtigo Fire, it still garnered more attention because the news was able to get out more quickly and because it was a larger settlement than the Wisconsin region. The National Weather Service writes that the myth about the Chicago Fire starting with a cow tipping over the lantern also helped the story of the Chicago Fire spread. It took almost two weeks for reports of the Peshtigo Fire to appear in newspapers.

But the Chicago Fire wasn't the only fire that burned in the Midwest that October. Between October 8 and October 11, 1871, there were at least 37 individual fires that historians have grouped into five major fires, including the Peshtigo Fire and the Great Chicago Fire. Thumbwind writes that the state of Michigan also saw a series of forest fires that began on October 8 as well, known as the Great Michigan Fire of 1871. And according to WLFI, the same period also saw fires in the Dakotas, Minnesota, Iowa, and Indiana.

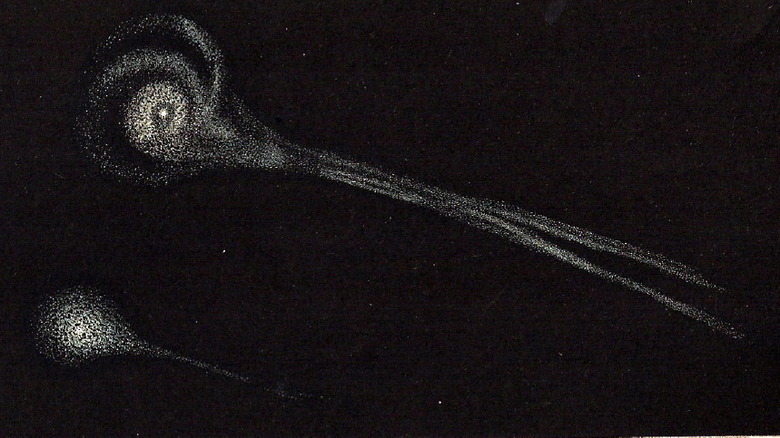

Biela's Comet

With so many fires igniting seemingly spontaneously in the Midwest, many speculated whether or not there may be something linking the fires more so than the weather or coincidence. One of the most popular theories has been to blame the fires on pieces of Biela's Comet. Because all of the fires in the region broke out at roughly the same time and eyewitnesses claimed that they'd seen "balls of fire" and blue flames, it was suggested that the fires were started by fragments of the comet that fell onto the Earth as the comet broke up over the Midwest, Richard Southall writes in "Haunted Route 66."

Ignatius L. Donnelly, a Minnesotan congressman who had written several works on the destructive power of floods and comets on past civilizations, first proposed this theory in 1883. Donnelly wrote about this theory in his book "Ragnarok: The Age of Fire and Gravel," but it would take over 100 years for the theory to be picked up, this time by author Mel Waskin. According to UPI, Waskin agreed with Donnelly's theory and wrote that "the descriptions of simultaneous fires breaking out, blue flames burning in basements and corpses found with no burn injuries all could be explained by a fire fueled by hot cometary gasses."

No help for days

Unfortunately, it took several days for news of the Peshtigo Fire to spread. According to the Peshtigo Fire Museum, the telegraph lines were destroyed in the fire, making it difficult for the people of Peshtigo to get the word out about the disaster. It took two full days after the fire for news of it to even reach the governor's office, and by that point, Governor Lucius Fairchild was already on his way to Chicago with relief supplies. But when Fairchild's wife, Frances Fairchild, heard about the Peshtigo fire while on the train, she reportedly stopped the train and rerouted one of the cars with supplies to Peshtigo.

Damn Interesting writes that with most relief supplies being dedicated to the aftermath of the Great Chicago Fire, Governor Fairchild diverted aid to Peshtigo under a special proclamation. As a result, over $150,000 was brought together to rebuild the town. Once the news finally began circulating, there was a widespread relief aid response.

Newspapers in England even wrote about the fire, and people started sending money and supplies all the way from London. "The January 20, 1872 State Gazette noted that three large bales were sent from London containing brand new white blankets," according to Relief to Wisconsin Sufferers. People in Belgium also ended up raising thousands of dollars for peoples' recovery after the Peshtigo Fire because there was a large immigrant community from Belgium in Wisconsin.

Wiped off the maps

While the town of Peshtigo was rebuilt after the fire, some towns that were destroyed ended up being wiped off of the maps for good. Door County Plus writes that the village of Williamsonville, which was once located just northeast of Brussels, was one such town that never recovered after the Peshtigo Fire. Founded by Fred and Tom Williamson in the 1860s, who ran a shingle mill operation, almost all of the town's 77 residents were either employees of the mill or members of the Williamson family.

Out of the 77 residents, only 17 survived the Peshtigo Fire. "Two men, suffering from the intense agony of the fires, resorted to ending their own lives by beating their heads upon a stump," according to Door County Plus. Those that survived were left with extensive burns on the feet, hands, and eyes. Door County Wisconsin writes that the only survivors of the Williamson Family were Tom and his mother.

Unlike Peshtigo, Williamsonville wasn't rebuilt, and instead, the site was marked as "Tornado" on a map seven years later. In 1927, Tornado Memorial Park was created on the site of the former Williamsonville to honor the memory of those who were affected by the Peshtigo Fire.

Peshtigo was rebuilt relatively quickly, with over 60 new buildings being put up by December 1871. And although some survivors chose to leave in the aftermath of the fire, there were many who stayed.