The History Of The Oldest Surviving Geological Map Of The Ancient World

So we all know the ancient Egyptians were architectural masters, right? The Pyramids at Giza, the Sphinx, Philae and Karnak temples, and much more typify not only the might and wealth of Ancient Egypt but the engineering prowess of the kingdom's 3,100 years of history (per the Australian Museum). In order to build such flawlessly hewn megaliths, how good do you suppose the ancient Egyptians had to be at quarrying, cutting, and transporting stone?

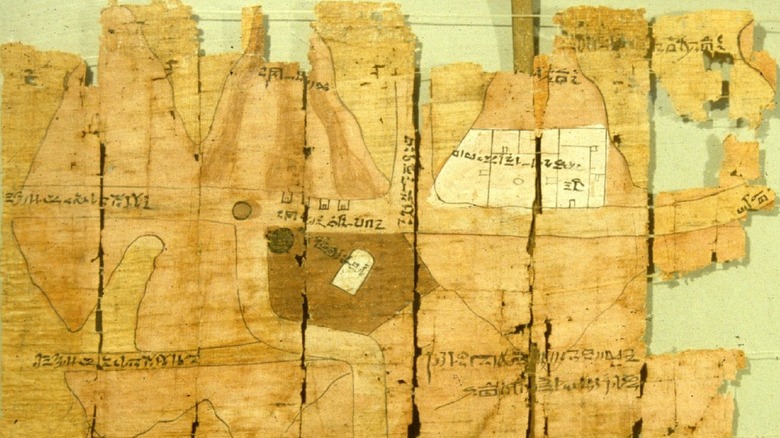

While we don't have extensive historical drafting plans for Egyptian monuments, we do have one document indicating exactly how ahead of the architectural curve the ancient Egyptians were: the Turin Papyrus Map. The map doesn't chronicle the building of a monument but rather details the geological composition of an area of Egyptian desert used for quarrying stone, Wadi Hammamat. Located east of Luxor in Upper Egypt (the southern part), Wadi Hammamat is littered with ancient watchtowers, ruins, forts, wells, and more (via Egyptian Monuments). It was also used as a trade route from the Nile River to the Red Sea for millennia.

The Turin Papyrus Map dates back to the reign of Ramses IV (1153–1147 B.C.E., per the Metropolitan Museum of Art) and is the oldest geological map of its kind, as sites like Ancient Origins describe. Its uncanny survival to the present — much like the medical compendium Eber's Papyrus — affords us an invaluable, unique window into the past. It also helps explain why the highly organized ancient Egyptians were so successful at building monuments.

On the hunt for bekhen stone

In the end, the Turin Papyrus Map was likely created as a guide for mining operations. Specifically, it indicates that the ancient Egyptians were on the lookout for what they called "bekhen stone," which includes certain varieties of sandstone, greywacke, and schist (via Egyptian Monuments). Wadi Hammamat also contains variously colored rock strata (as you can see in the picture above), including dark basalt and smaller deposits of red, pink, and green stone. The latter wouldn't have been used in large monuments like limestone or granite because it was too fragile, but would have been incorporated into detailed work in color palettes for paint and on sarcophagi, shrines, and especially statues.

As the Journal of the Faculty of Tourism and Hotels discusses on Research Gate, bekhen stone — typically greyish-green — was quarried on a case-by-case basis in specific missions dispatched to Wadi Hammamat. Different staff were hired at certain rates and were overseen by administrators who liaised with various governmental branches. Wealthier people and aristocracy commissioned artwork using the very in-demand stone.

The Turin Papyrus Map was apparently made by one Amennakhte, son of Ipuy, whose job title was, awesomely, "Scribe of the Tomb" (via Ancient Origins). Some believe that the map was made for the High Priest of Amun in Thebes, who would've communicated its content with Pharaoh Ramses IV. If this is the case, it could have been made after the fact as a record of an operation rather than beforehand as a guide.

Map and legend of Wadi Hammamat

The Turin Papyrus Map is unique beyond being the oldest geological survey map in the world. Most pointedly, as Ancient Origins explains, the map depicts a to-scale region of Wadi Hammamat at a time when no consistent scales existed. The map isn't abstract in any way and doesn't warp the relative distance between its objects. It does, however, uniformly expand or contract its scale for certain areas, which varies from 50 to 100 meters for each centimeter of the map.

The map covers a 15-kilometer (9-mile) swath of the Wadi Hammamat desert and relates topographical details like hills and inclines using cones and wavy lines, respectively (via History Today). It also uses different color dots for different types of stone. Bear in mind that in the present day, the narrowest span of Wadi Hammamat covers a 178-kilometer-long drive (110 miles) from the Red Sea coastal village of Quseer to the closest Nile-based town Qift (as we can see on Google Maps). This means that the Turin Papyrus Map depicts an extreme, detailed zoom of a very particular area.

The Turin Papyrus Map is drawn from the perspective of one coming up the Nile from Lower Egypt in the north, meaning that the Nile's west bank is on the map's right side. Sections of the map also, amazingly, function like a legend. Additionally, the map depicts four small buildings for on-site gold-workers, as well as sites of gold-bearing quartz.

Revert it to papyrus

Besides its topology, geological accuracy, to-scale representation, and legend, the Turin Papyrus Map is exceptional simply because it's made from papyrus. Papyrus, like any parchment, fades and crumbles. History has left us a decent amount of papyri (individual scrolls, not the material) from ancient Egypt, but this only illustrates how extensively papyrus was used and how well it's preserved in dry, desert air. The oldest extant papyrus, as Smithsonian Magazines says, dates back to when Pharaoh Khufu commissioned the Great Pyramid in Egypt's Old Kingdom (2686-2181 B.C.E., via the Australian Museum).

The entire papyrus-making process is incredibly painstaking, as the Metropolitan Museum of Art describes. Typically, papyrus was rolled up with the writing on the inside of a scroll to protect it. The Turin Papyrus Map, however, was folded. And it wasn't folded into quarters like a document destined for the bin, but in an accordion fashion "in the manner of a modern road map," as Ancient Origins cites. So you pick it up, hold it in front of you, pull apart the front and back folds, and it unfolds like a treasure map with the front of the papyrus facing you. Perfect for a surveyor at a mining site.

Folded ancient papyrus is rarer than not and sometimes not opened because it's brittle enough to simply crumble. Oftentimes, as a study in Applied Physics A describes on Springer, modern researchers use computed tomography to virtually unfold a piece of papyri and thereby safeguard its contents.

A long path to reconstruction

When the Turin Papyrus Map was discovered between 1814 and 1821, it was in crumbled tatters. As Ancient Origins explains, antiquities collector and French Consul General in Egypt, Bernardino Drovetti, discovered the map's fragments in a private tomb in the workers' community of Deir el-Medina near present-day Luxor. Deir el-Medina, or Set-Ma'at by its original name, is one of the least glamorous — yet dramatically important — archaeological sites of Ancient Egypt, as World History explains.

Founded from 1541-1520 B.C.E., about 400 years before the creation of the Turin Papyrus Map, Set-Ma'at was designed from the ground up as a self-contained village for the artisans and craftsmen of Thebes in Upper Egypt. The entire site provides critical insight into the daily lives of Egypt's working-class and explains Egyptian workflow from the nearby quarry of Wadi Hammamat to its stones' final, artistic forms. It's unknown whether or not the map was used by the person in whose tomb it was found.

After being purchased by King Charles Felix of Sardinia, the map wound its way to the Museo Egizio (Egyptian Museum) in Turin, Italy, where it remains to this day. At first, folks thought the map's fragments came from three different papyri, but reconstruction in the early 1900s revealed that the whole thing was actually one 2.8-meter-long (9 feet), 0.41-meter-tall (1.3 feet) map. Even though researchers discovered errors in the map over time, these weren't corrected until the 1990s.

Modern-day treasure hunts

At present, the entire Wadi Hammamat region is the center of an ambitious archaeological venture dubbed "The Wadi Hammamat Project," founded in 2010. The project's rather extensive goals involve using a multidisciplinary approach to mine the region (so to speak) for any and all data and evidence that can tell us more about ancient Egypt. Researchers check things such as the time and depth of quarrying, how the area's administrative organization changed over time, what new technologies were used during that time, and how these changes interacted with the region's various ethnic and kin groups. They regularly released research reports to the public, although it seems like those reports petered off in 2015.

Contrarily, others have used the Turin Papyrus Map to set forth on modern-day gold hunts. As National Geographic quotes geologist Leonard Karr, "This iron stain is what the old-timers would vector in on. Those are iron oxides. You see that yellow, you know you have an iron sulfide. That's a really good indication that you might have gold." At the time of that article's writing in 2016, Karr was employed by Canadian-based Aton Resources Inc., a "gold exploration and development company" (as the Aton website says) seeking to use the approximately 3,150-year-old Turin Papyrus Map to "strike it rich" in Egypt.

Granted, for all the map's markings of bekhen stone, the ancient Egyptians were also well aware that Wadi Hammamat contained gold. But according to National Geographic, these ancient miners "just scratched the surface."