The Truth Behind The Tiny Piece Of Art Left On The Moon

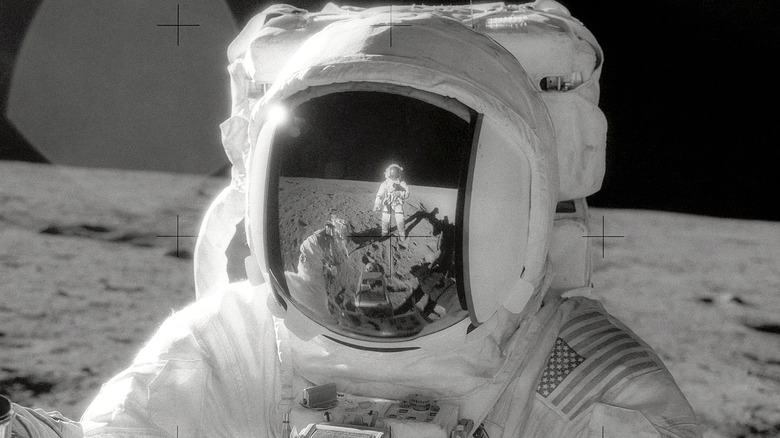

Traveling to the moon is not the kind of trip where you can just pay a little extra for a suitcase over the weight limit; it's a death-defying exercise in physics, mitigated by precise calculations involving mass, velocity, and time. Per PBS's "History Detectives," each item aboard a spacecraft contributes to its mass, so each one must be accounted for. As retired Apollo 12 astronaut Alan Bean put it, all personal items astronauts brought aboard had to be "laid out on a table, photographed, numbered ... so everything that I took for personal reasons, NASA knew about."

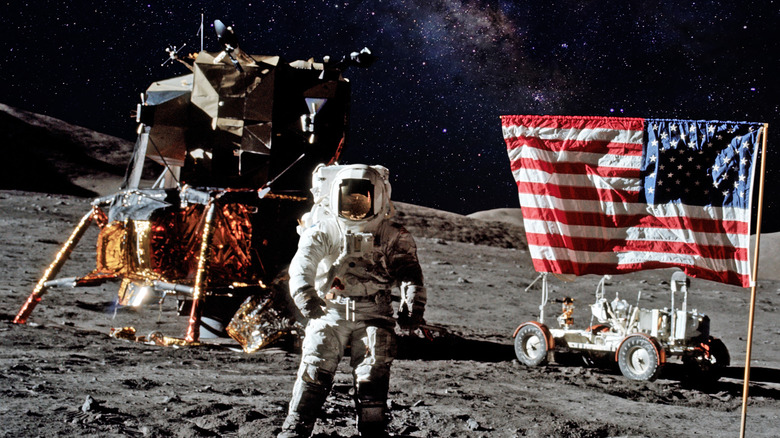

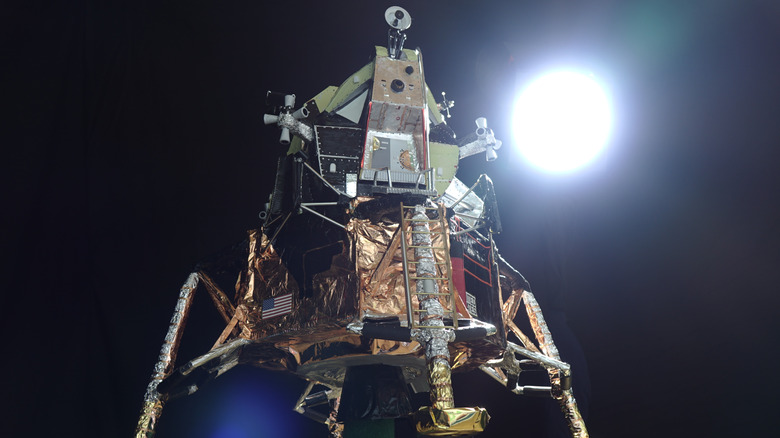

And yet, it's quite possible that one of the legs of the 1969 Apollo 12 mission's lunar module "Intrepid" — which, according to Encyclopedia Astronautica, is still on the moon's surface today — includes a stowed away miniature art museum referred to as "The Moon Museum." Strap in: This is a wild ride back and forth in both time and space.

According to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) "The Moon Museum" is a tiny ceramic wafer measuring 9/16 inches by 3/4 inches. Its surface holds miniaturized artworks by six major artists of the period, including Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg. The only artist of the six still alive today is sculptor Forrest "Frosty" Myers.

To be clear, the wafer in MoMA's collection is not the one that may have gone to the moon. Rather, as noted in the work's catalog entry at MoMA, it is another wafer from the edition of about 40 originally produced at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey in 1969.

Teasing out the truth about The Moon Museum

Let's go back to the beginning. The idea of artwork on the moon — whether officially sanctioned by NASA or not — isn't that far-fetched. As reported by "History Detectives," NASA has always been rooted firmly in rigorous science, but almost from its infancy in the late 1950s, the Agency also began working with artists to create works that reflected the excitement around space exploration. During an interview with "History Detectives," sculptor Forrest Myers noted that he was so enthusiastic about space flight that he channeled it into the idea of "get[ting] six great artists together and making a tiny little museum that would be on the moon." NASA was non-committal. As Myers put it, "at first, it seemed promising, and then we realized we were just getting the runaround. They never said 'no', I just couldn't get them to say anything."

Myers was undaunted. As reported on "History Detectives," he next approached EAT (Experiments in Art and Technology), an organization that brought artists and engineers together to collaborate on projects. EAT put Myers in touch with Bell Laboratories engineer Fred Waldhauer, who miniaturized all six works and used Bell's telephone circuitry technology to print them onto the edition of ceramic wafers.

An inconclusive lunar investigation

Fred Waldhauer had a contact at Grumman Aircraft, the company contracted to build the "Intrepid," who agreed right away to help place the wafer aboard the lunar module. Myers received a telegram he's kept ever since, confirming the placement of "The Moon Museum" from a "John F." Attempts by "History Detectives" to learn the true identity of John F. yielded nothing: Waldhauer is dead, and they couldn't identify John F. as an engineer working for Grumman in 1969. The name was likely a pseudonym, which is prudent since any assistance he provided could have ruined his career if it came to light during his lifetime.

Despite not being able to confirm directly that "The Moon Museum" made it to its intended destination, "History Detectives" shared one more tantalizing data point. Richard Kupczyk — who worked at Grumman as a launchpad foreman — demonstrated (using a near-replica of the "Intrepid" housed at the Cradle of Aviation Museum) how engineers clandestinely stowed photographs between the very fine layers of metallic blankets aboard the lunar model. This flies directly in the face of NASA's rules, but Kupczyk emphasized that "never was there anything that was done to the spacecraft that would be a safety issue." Since Grumman engineers' stowaway items are still on the lunar surface aboard the "Intrepid," it follows that "The Moon Museum" may remain up there, too.

So what really happened? And what's next for art in outer space?

Ultimately, definitive answers to questions about "The Moon Museum" are impossible. So many of the people who could offer the certainty we crave are dead, so absent a follow-up mission to inspect the moon-based remains of lunar model "Intrepid," the fate of "The Moon Museum" is in a long-term gray area. Those who think this museum in miniature is on permanent display on the moon can reasonably believe it, and those who think it isn't there have reason to believe that, instead.

But does it even matter? Given the fascinating story behind the work's creation — a true collaboration between art and science, with the possibility of some light national security intrigue for a garnish — the exact location of "The Moon Museum" isn't really the point anymore. As space artist and Carnegie Mellon University, Art Professor Lowry Burgess put it to Wired, "I'm not going to get into [that debate]."

The legacy of "The Moon Museum" is fascinating and long-reaching: Artists have never stopped trying to send their work into space, and over the decades, alliances among artists, NASA, and independent space exploration organizations have developed, resulting in projects like The MoonArk Moon Museum (2016), a collaborative work organized by Burgess and sent to space aboard a Google Space X ship.

If "The Moon Museum" reached its intended destination, it's probably intact and well-preserved, because, per NASA, the moon's atmosphere doesn't contain oxygen, which hastens decay here on Earth. If travel to the moon becomes commonplace in the future, perhaps this miniature gallery will become a popular tourist destination.