Here's How Sitting Bull Got His Unique Name

The U.S.' 19th-century westward expansion tends to evoke excessively romantic visions of the past: Gritty and rock-hewn cowboys lassoing their way to rugged, heroic individualism; Idealized notions of American "can do" attitude that casts the wan whining of the internet-beleaguered generation in a truly absurd light; Mythologized undertakings like the Oregon Trail (1841-1869) that claimed at least 20,000 lives as its diseased caravan trundled towards the future coastal bliss of California (via Bureau of Land Management). All in all, it was a rough, pivotal time in history marked by equal parts brutality and bravery.

Bit by bit, over the 19th century, the current shape of the United States took form, as the New York Public Library depicts. The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 bought a massive chunk of the Midwest and Pacific Northwest from the French in a move that "very nearly destroy[ed] the republic," as one historian stated (via History). American settlers in Texas joined up with Tejanos (Texans of Spanish descent) to join the union in 1837, and then the American southwest came under U.S. control in 1848 following the Mexican-American war (also via History).

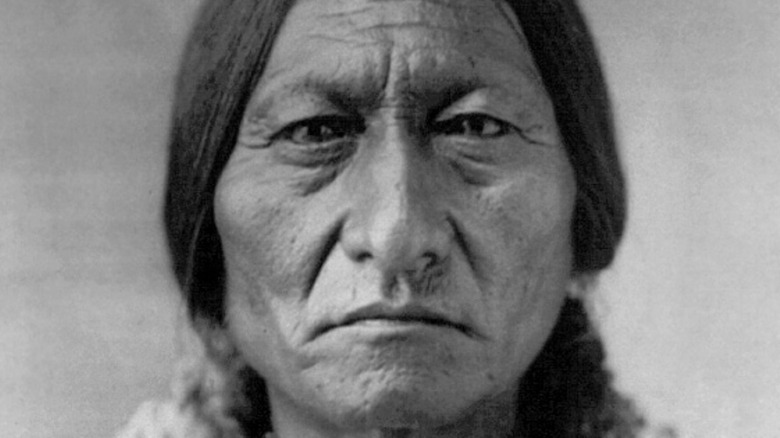

As the "United" States fell into, and recovered from, its Civil War (1861-1865), folks who settled into the nation's newly defined borders came head-to-head with indigenous peoples who'd been driven aside since day one. One of them, the legendary Lakota chief Sitting Bull (1831-1890), stands out in memory not just for his unparalleled battle prowess, but for his very name.

From Slow to Sitting Bull

Many folks recognize Sitting Bull's name before the man, and might remember his fight against General Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876. Before Sitting Bull carried that name and led the Lakota on the American northern plains, though, he'd already earned a variety of monikers.

Sitting Bull was born a Hunkpapa Lakota in the northern part of modern-day South Dakota, near the state's Grand River in an area dubbed "Many Caches" by its tribes for its stashes of food, via the Akta Lakota Museum Cultural Center. The Hunkpapa, along with the Blackfeet band and Standing Rock Sioux tribe, formed the Great Sioux Nation that Sitting Bull would later defend in 1890 at the cost of his life (also via the Akta Lakota Museum Cultural Center).

Sitting Bull's father was an adept hunter who leaped over gullies while hunting bison, and so earned the name "Jumping Bull" (via AAA Native Arts). His son, originally called "Jumping Badger" (via History), proved a careful, deliberative child with an almost meditative air. And so, he was re-named Slon-ha, or "Slow," and later nicknamed "Sacred Stand." By the time Slow reached 10 years old he'd killed his first bison, and by 14 he'd counted coup (touched an enemy opponent without killing him) on a raid against the Crow tribe. For this and his overall indomitable demeanor he was named Tatanka-Iyotanka, which literally translates as "a large bull buffalo at rest," aka "Sitting Bull" (per Native Partnership.)

Fearless and dignified to the end

Sitting Bull saw his first white men — U.S. Army soldiers — on the raid when he earned his name. The next year, in 1846, he fought against that very army in the Battle of Killdeer Mountain (via the Akta Lakota Museum Cultural Center). In 1865, he led a siege against Fort Rice in North Dakota, and three years later he became head chief of the greater Lakota nation. Sitting Bull became equal parts legend among his people and relentless thorn in the side of the U.S. Army. One notable anecdote describes him quietly smoking a pipe amid a hail of bullets near a battle along Yellowstone River.

The Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876 came on the heels of white settlers breaking the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 by entering the Dakota Territory's Black Hills to mine gold. Many tribal Americans left their newly demarcated reservations and joined Sitting Bull in rebellion. George Custer, commanding the Seventh Cavalry, attacked with around 600 troops, which he divided into three separate battalions. Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse (1840-1877) soundly defeated them, including killing Custer and all of the men under his direct command — about 260 in all (via History). It was the worst defeat the U.S. Army suffered during the Indian Wars (also via History).

Ironically, Sitting Bull didn't die in battle. He was living on the Standing Rock Reservation when Native American police tried to arrest him — it was feared he was going to incite rebellion. He was shot and killed during the attempt on December 15, 1890 (per another posting by History)