The Victorian Era's Obsession With The Occult Explained

The tarot, mediumship and Spiritism, seances and Ouija boards, prophecy and clairvoyance, Rosicrucianism's rise in popularity and the advent of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn: Take all of these esoteric, arcane, and magical traditions and toss them in a pot, stir for about a century, and blammo: we've got the entire Victorian era's occult craze.

It's no exaggeration to say that the Industrial Revolution had an impact on almost every aspect of life during the 19th century, particularly during Queen Victoria's reign. She was born in 1819, ascended to the throne in 1837 and reigned until her death in 1901, a period matched only by an equal and opposing preoccupation with all things mystical. Professions were turning mechanized. People obeyed the clock and not the sun. Lives became dependent on and defined by all things quantifiable, tangible, and rational. As The New Yorker summarizes, the mysteries of nature and God felt stripped away, and despair settled in as folks were forced to ask, "Is there nothing more? Am I mere mechanism, too?" This sense turned inward and ballooned into the desire for something beyond what the eyes could see and hands could touch, but separate from — as people saw it — the failed practices of a religious past that did nothing in the end but engender a dehumanizing present.

The occult "possessed" the minds of people not only in Queen Victoria's Great Britain, but basically anywhere that agriculture rolled over to industry, particularly in the United States, France, and to a lesser extent, Germany. And the marks of that era, mystical and technological alike, persist to the present.

Birthed on the heels of the Enlightenment

The Victorian obsession with the occult had been building for centuries, hand-in-hand with the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment (roughly 1600-1815) marked, without hyperbole, one of history's most radical, fundamental shifts in human thought and perception, from which the entire world subsequently flowed. As History explains, the Enlightenment encompassed what we call the "Scientific Revolution," and gave us not just modern chemistry, biology, physics, medicine, and lives defined by technological doo-dabs, but the belief that the world existed to be deciphered, and human life to improve.

The Renaissance had set the stage. Folks in Renaissance Italy (about 1350-1600) looked back to the glories of past art and republicanism for inspiration, as History relates in its overview, and wound up believing that the future was something to make, not endure. The greatest times of humanity were not past and relegated to scholasticism (analyzing and debating religious texts), but ahead and a by-product of human will and self-improvement. This way of thinking, which spread through Europe at the time, is "humanism." Anytime someone says, "I can do it, I can be better," they're practically quoting the Enlightenment's humanist ethos. Rene Descartes, Isaac Newton, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau: these philosophers and more defined the back-and-forth discoveries and discussions of the age. But by the time Queen Victoria took the throne, many folks were left feeling empty and wanting a reconnection to the divine.

When magic looks like science

The Spiritism, mediumship, magical practices, and the like of the Victorian era weren't new inventions. They were rediscoveries of ancient pagan and occult practices reinterpreted through the scientific age. The Enlightenment necessitated a diminution of traditional religious doctrine, particularly of the Christian variety, which allowed latent, submerged but not forgotten, ways of the past to rise once again. Such practices took on a "scientific" tenor, couched as they were between the natural sciences of the past and the hard scientific formality of modernity.

Alchemy is one example (circa the 1600s, per Live Science), built on the old notion of substances as "perfectable" in the way that the heavens were perfect because they were nearest to God, unlike Earth. Investigate and experiment with the right combination of materials and ingredients, like chemistry, and bam: Lead becomes gold. Freemasonry led to 17th-century Rosicrucianism, a sort of remixed combination of a bunch of ancient religions (via the Rosicrucian Order), which yielded to the Order of the Golden Dawn in 1887 in Victorian London. Each was a more rigidly formalized version of magical practices than the last, with rankings, levels, initiations, and ultra-standardized rituals. If you want to see exactly how systemized — imitating the form of science — the Order of the Golden Dawn is, have a look at their curriculum of the Open Source Order of the Golden Dawn. All such lines of inquiry were attempts to see beyond the obvious, denigrative, material truth of the then-modern world.

Spirit over matter, and life after death

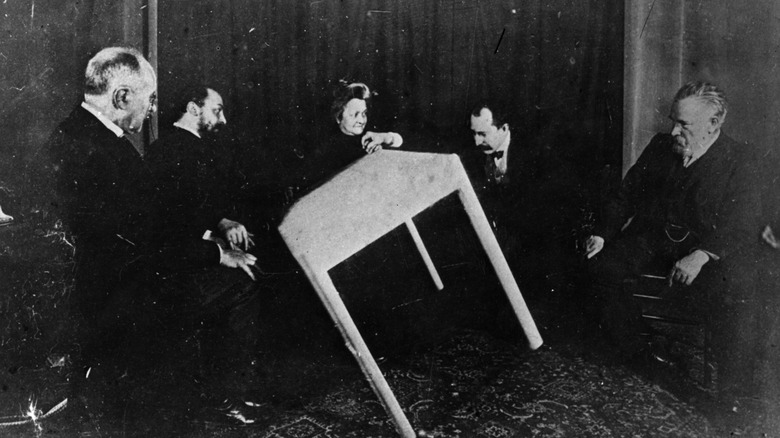

While some people in the Victorian era engaged in systematized versions of magical inquiry like that of the Order of the Golden Dawn, others went the totally opposite direction towards all things "spiritual." Seances, hypnotism and mesmerism, mediumship, divination, clairvoyance: These all fall under the header of "Spiritism," which was all the rage from the mid-Victorian era to the beginning of the 20th century. We're talking celebrity mediums, levitating tables, ectoplasm spewed from the mouth, voice-swapping when communicating with the Great Beyond, you name it (as The New Yorker describes).

Queen Victoria herself was a big believer in Spiritism, and attended seances after her beloved husband Prince Albert died in 1861 (via The Conversation). Across the Atlantic, Spiritism took off following the end of the Civil War in 1865. The creation of "talking boards" (like the brand name "Ouija," via the Smithsonian) aided such endeavors, while the rise of mesmerism and hypnotism reinforced hope in the power of spirit over matter (via Victorian Web).

Looking at these examples alone, it's not too hard to see why Spiritism took root. Not only had life and careers become mechanized and depersonalized, but so had war and death. Those living in such an age of spiritual ennui desperately wanted to believe in life after death. Those whose loved ones had died by the distant, detached cannon fire of battlefields wanted to feel some personal, human connection to those lost.

Photography and ritual drug use

Not only did Victorian Spiritism and occult practices develop as a reaction to scientific progress, they were aided by technology, too. Photography, in particular, helped buoy the popularity of the occult. Mediums often doctored photographs to provide evidence of "spirits," such as ghostly figures or hands intruding into photos (as The Old Operating Theater depicts). Researchers John Pavlik and Shravan Regret have gone so far as to suggest that the Victorian "mixed-method" approach to photographic manipulation, especially the understanding of visual illusions and stereography (overlapping right-left images to give something a 3D look), prefigured everything from cathode ray tubes to virtual reality (VR) (via Rutgers).

Less mechanical of an influence, but no less scientifically aided, were Victorian drugs. Laboratory-made chemicals like morphine piggybacked on the invention of the hypodermic needle in 1840 (via Welcome Collection). People could not only eat or smoke drugs, drop them into drinks in liquid form (like ether), dissolve them into powders like laudanum (a powdered opium mixed with alcohol), but inject them directly into the body. Many of these drugs were meant for medical use, but could be bought at any random apothecary (via the National Trust for Scotland). Those attracted to the occult sought such drugs for their mind-altering "clairvoyant and telepathic effects," including folks such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, writer of "Sherlock Holmes" (also via Welcome Collection). Also on the list? Nitrous oxide used as a global anesthetic, which Queen Victoria herself rather enjoyed (via Science History).

Celebrity occultists and class distinctions

As Victorian occultism rose in popularity, so did celebrity occultists. In France, figures like poet and artist Éliphas Lévi (1810-1875) made a huge impact on generations of occultists with writings on Gnosticism, Kabbalah, Rosicrucianism, and much more, as St. John's Seminary describes. Incidentally, we have Lévi to thank for popularizing the famous "Baphomet" image that's come to be adopted by the Church of Satan (via Britannica). In the U.S., Helena Petrovna Blavatsky formed the Theosophical Society in 1875, which sought to fuse western magical traditions with eastern mysticism into a kind of universal, pan-religious belief system, as the Theosophical Society in America explains. Meanwhile, mediums like Cora Hatch grew to fame and acclaim, as shown by a 1859 New York Times article about her lecture "The Unity of the Law of God."

Amid ardent believers and blatant charlatans, some folks in the Victorian era got involved in the occult simply because it was something to do. Friends went to séances, society at large was interested, and so on. Young girls, for instance, as The Old Operating Theater explains, might go to a medium just to ask the age-old question, "What boy likes me?" The occult was also a way for people to reach across industry-forged class gaps that were widening at the same time as they were becoming more flexible. In a very real way, the Victorian era forecasted modernity's "everyone find what works for them" attitude towards spirituality.