The Real Reason The British Empire Collapsed

The British Empire was the largest empire in history. At its zenith in 1920, the empire covered an astonishing 25% of the world's landmass, which equated to some 13.71 million square miles (via National Archives/Statista). For context, the U.S. Census Bureau calculates the United States' landmass at 3,796,742 square miles, which means that the British Empire was some 10 million square miles larger — greater than the landmass of the Russian Federation, which covers "only" 6.6 million square miles.

During the reign of Queen Victoria, which began in 1837 and ended with her death on January 22, 1901, the British Empire established not only its vast size but also a dominant position in trade, diplomacy, and military strength (via Britannica). It had also left an enduring legacy across a league of Anglosphere nations, namely Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States.

So, how did the British Empire, which was famously referred to as "The empire on which the sun never sets," go from unbelievably powerful at the dawn of the 20th century to dissolving just a few decades later? From friends and foes to conflict and currency, here are the real reasons the British Empire collapsed.

The British Empire was too big and too expensive

Governing 13.71 million square miles and some 538 million people came at a substantial price (via Guinness World Records). According to the British politician Denis Healey, quoted in The Economic History Review, "As early as 1880, the British Empire was producing an economic return lower than investment in Britain itself, while to preserve it the British taxpayer was paying two and a half times more for defense than the citizens of other developed countries." Historian Patrick O'Brien concurred, "The majority of the English people cheerfully and even proudly shouldered a tax bill for an empire from which they derived very little in the form of tangible pecuniary gains."

The feasibility of maintaining such a vast landmass became violently apparent during the Second World War. Writing in "The Rise and Fall of Great Powers," historian Paul Kennedy observed, "When Britain had to channel so many of its resources to the war in Europe as well as Africa and the Middle East, there was little that could be spared for the relatively late arrival to the war in Southeast Asia." Kennedy was referring namely to Japan's attack on Singapore, which exposed Britain's inability to fund an adequate empire-wide military.

The First World War compromised Britain's finances

According to the Grenada Television documentary "End of Empire," the huge financial burden of the First World War hit Britain's Royal Navy hard, allowing the United States and Japanese navies to catch up with the Royal Navy's capabilities. As the Inquiries Journal pointed out, Britain knew that it would struggle to win a new naval arms race owing to the debt incurred funding the First World War. Also, in 1921, the nation's gross domestic product was just 87.1% of its 1913 level; it would take until 1925 to reach pre-war GDP.

This issue was addressed in the Washington Naval Treaty, which agreed to limit naval construction in order to avoid an arms race and further war (via Department of State). Britain's reluctance to invest in its navy meant it was neglecting its main military strength, because unlike its continental neighbors, the bulk of Britain's power had always been wielded by the Royal Navy. Alas, the Washington Naval Treaty did little to prevent the rearmament that precluded the Second World War, which proved to be financial ruin for the British Empire.

The Second World War compromised them even further

The Second World War did more than compromise Britain's economy. According to Britannica, the existential conflict drained the nation of its foreign financial resources. And as Britain planned how to move from a war economy to a peacetime economy, U.S. President Harry Truman announced the end of the two countries; lend-lease deal on September 2, 1945, which Britain had depended on for both arms and necessities. Consequently, famed economist John Maynard Keynes negotiated a $3.75 billion loan from the United States and a smaller payment from Canada in March 1946. The loans were finally paid off 60 years later in December 2006 (via Gov UK).

With Britain bankrupt and war weary, the nation's attention was inward rather than outward. According to the British Legion, over two million homes across the United Kingdom were either damaged or destroyed. Industries from aviation, which was now far too big, to mining and railways, which were depleted of staff and equipment, had to be redrawn and repurposed (via Brittanica). And with two new superpowers in the form of the United States and the Soviet Union, both of which were hostile to European colonialism, the British Empire's position had become untenable.

Britain's military losses during the Second World War damaged its prestige

Of course, Britain emerged victorious in the Second World War, but that came after a string of defeats earlier in the conflict. Among the worst of these was the fall of Singapore, which occurred from February 8 to 15, 1942 (via Historic UK). During those savage seven days, Japanese troops led by Tomoyuki Yamashita overwhelmed the larger British force, eliminating all notions of European superiority. According to Hillsdale College, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill described the fall of Singapore as, "the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history." The event was the culmination of Britain's weak naval budget and the aforementioned Washington Naval Treaty that tried and failed to prevent an arms race.

Historian Raymond Callahan spoke of the battle's historical weight, "The fall of Singapore was a pivotal event with enormous consequences ... Not only was it a military defeat, it was a shattering blow to Great Britain's prestige and marked the decline of the Western era in Southeast Asia."

The fall of Singapore didn't just shatter Britain's prestige, it also shattered any illusions that the British cared about Singapore. Max Hastings wrote, "The British very quickly made it plain that escape was something that was reserved for white people ... the British, by their actions, showed they simply did not care. And this destroyed, in a matter of weeks, centuries of instinctive respect by colonial subjects towards the British imperial power, and so it deserved to."

The United States did not approve of European colonialism

Although it had ventures in Peurto Rico, the Philippines, and the Pacific, the United States did not approve of the European model of colonialism. According to historian Ebere Nwaubani in "The United States and Decolonization in West Africa, 1950-1960," President Harry Truman once remarked, "I had always been opposed to colonialism. Whatever justification cited at any stage, colonialism in any form is hateful to Americans. America fought her own war of liberation against colonialism and we shall always regard with sympathy and understanding the desire of people everywhere to be free of colonial bondage."

The United States has a long history of anti-imperialist sentiment. When the United States annexed the Philippines in 1898, a group of public figures, including Andrew Carnegie and Mark Twain, founded the Anti-Imperialist League, whose platform stated, "We hold that the policy known as imperialism is hostile to liberty and tends toward militarism, an evil from which it has been our glory to be free" (via Library of Congress/Fordham University).

Anti-imperialism was also evident in America's isolationism before Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. According to the State Department, the powerful isolationist lobby campaigned for the United States to avoid conflicts in Europe and Asia and generally remove itself from international politics. Such positions were the antithesis of the colonial model.

And neither did the Soviet Union

According to the New Yorker, anti-imperialists across the world saw the Soviet Union as a beacon. This is because anti-imperialism was central to Bolshevist thought. For example, Vladimir Lenin dubbed imperialism as, "the highest stage of capitalism," adding that, "Imperialism is that stage of capitalism when the latter, after fulfilling everything in its power, begins to decline" (via Fourth International).

When Joseph Stalin secured his brutal rule over the Soviet Communist Party in 1929, he enforced Lenin's ideology as fact rather than subjective policy (via Britannica). He had been Soviet premier since 1922, but it had taken seven years to eliminate rivals and establish his dictatorial leadership model, which would later be dubbed Stalinism.

By the end of the Second World War in 1945, the split between the British Empire and the Soviet Union began to widen, culminating in the Berlin Airlift of June 1948, considered by most historians to be the first major incident of the Cold War (via State Department). Hypocritically, Stalin was committed to extending the Soviet Union's sphere of influence, causing the Chinese to describe the Soviets as "a social imperialist superpower," according to Albert Szymanski. This new imperialism was at the expense of both the United States and, most damagingly, the British Empire.

Winston Churchill lost the 1945 election

Before the results of the postwar election were announced on July 26, 1945, Prime Minister Winston Churchill was confident of a win. After all, he had overseen Britain's victory in the greatest war the world had ever seen (via Imperial War Museum). However, Churchill would lose to Clement Attlee's Labour party, who promised sweeping social reforms that included employment, housing, social security, and state healthcare. According to the Churchill Archive, the new Labour government supported Indian independence and devised plans that "deeply worried" Churchill.

According to historian Peter Clarke, Churchill wished to delay Indian independence. In fact, the war leader told Lord Linlithgow in 1937 that he wished, "to see the British empire persevered for a few more generations in its strength and splendor," although he conceded that the empire's days were numbered (via The Guardian). On March 6, 1947, months before the partition of India on August 15, Churchill said, "It is with deep grief I watch the clattering down of the British Empire with all its glories and all the services it has rendered to mankind" (via International Churchill Society).

Britain's postwar government did not care for colonialism

With Clement Attlee as Britain's new leader, the British empire's collapse was likely to be hastened. According to the Cambridge University Press, Attlee was committed to Indian self-governance, adding, "The colonial problem will not be solved by a combination of an eye to business and humanitarian sentiment. Nor on the other hand will it be solved by looking backwards and imagining that we can recreate the conditions of a past age ... [Britain must] set aside sentimental imperialism and take a realist view of our problems."

Attlee's instructions to Lord Mountbatten, who oversaw the end of British India, were as blunt as they could be, "Keep India united if you can. If not, save something from the wreck. In any case, get Britain out" (via Outlook India). According to historian Vernon Bogdanor, Churchill greatly lamented the fall of the empire. Churchill told his secretary that his career had been, "the maintenance of the enduring greatness of Britain and her Empire," and that he had failed in this objective, adding, there was no point "being wise and benevolent if no one listens to you and if you are not in a position to enforce your will."

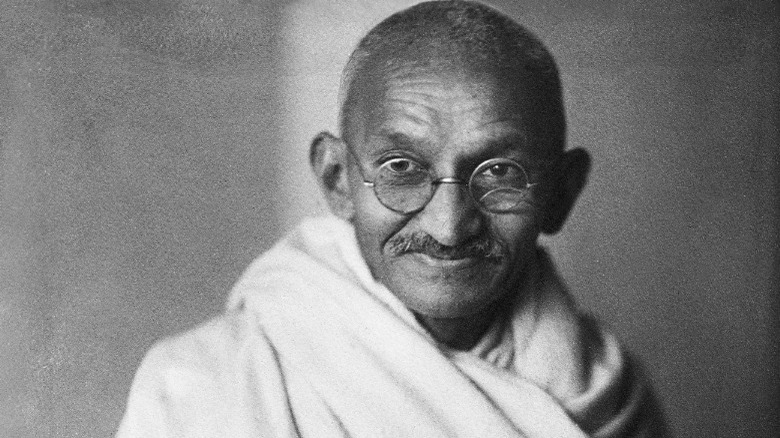

Mahatma Gandhi led the calls for Indian independence

According to the International Churchill Society, the British Empire's authority started to fade from the early 1930s onwards. A significant policy change came in 1935 with the Government of India Act, which afforded a certain amount of self-governance to the Indian sub-continent (via Oxford Reference). According to the nonprofit website Constitution of India, scholar Andrew Muldoon argued that the act was, "Arguably the most significant turning point in the history of the British administration in India," and that the act aimed to, "[continue] the British control of India, and deflect the challenge to the Raj posed by Gandhi, Nehru, and the nationalist movement."

The Indian National Congress party did not mince words in their appraisal of the act, calling it a "Slave constitution that attempted to strengthen and perpetuate the economic bondage of India." Mahatma Gandhi, a former member of the Congress party, was not placated, either. A trained lawyer educated at the University of London, Gandhi was the face and leader of Indian nationalism, mounting three independence campaigns in 1920–22, 1930–34, and 1940–42 (via Britannica).

Using his talents of mediation and reconciliation, Gandhi's ideas of non-violent nationalism resonated with people not just through India's rigid caste system, but across Britain, Europe, and the world. Speaking of Gandhi's legacy, Martin Luther King Jr. said, "If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, thought and acted, inspired by the vision of humanity evolving toward a world of peace and harmony. We can ignore Gandhi at our own risk" (via Miami University).

Other protest movements gained traction across the British Empire

According to Britannica, India's independence galvanized colonies throughout the empire, including Burma, Ghana, British Malaya, Cyprus, Nigeria, Singapore, Sierra Leone, Uganda, and Kenya. A major event in this wave of decolonization was the 1948 Accra riots. According to the Ghanian Museum, the riots occurred after the killing of three Ghanaian World War II veterans on February 28, 1948.

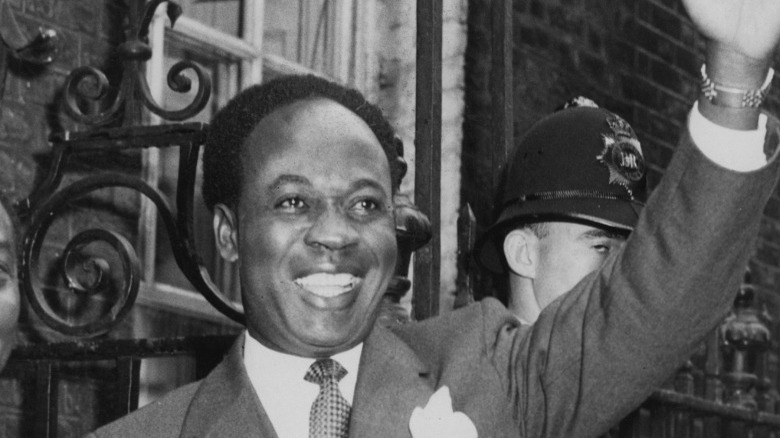

The killings happened against the backdrop of economic sanctions on European goods, which began weeks prior on January 28 and ended exactly a month later on February 28, following an agreement with European firms. As Ghanaian buyers realized that the agreement was not fulfilling their expectations, chaos ensued as Superintendent Imray, the British head of police, struggled to contain the protest and destruction. A state of emergency was declared and six anti-establishment leaders were arrested, including Kwame Nkrumah, all of whom were released a month later.

Having tested the British regime, Kwame Nkrumah formed the Convention People's Party and campaigned for Ghanian self-governance. And on March 6, 1957, he declared Ghana's independence and became the country's first post-colonial leader (via BBC). This pattern would be seen throughout the British empire during the immediate post-war era.

The Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis in 1956 was a landmark event in postwar British history. Historian Sylvia Ellis writes how the Suez crisis, "signified the end of Great Britain's role as one of the world's major powers." The crisis arose when Gamal Abdel Nasser, the president of Egypt, nationalized the Suez Canal, a vital waterway that had been owned by the Suez Canal Company, a British-French enterprise (via Britannica). The move incensed British Prime Minister Anthony Eden, who is said to have exclaimed, "What is all this poppycock you've sent me about isolating Nasser and neutralizing Nasser? Why can't you get it into your head I want the man destroyed? I don't care if there's anarchy and chaos in Egypt. I just want to get rid of Nasser" (via The Guardian).

Eden's hawkishness was not just bluster. Britain and France negotiated a secret invasion plan with Israel, which was launched by 10 Israeli brigades on October 29, 1956. As Egyptian forces were outmaneuvered by Israel's rapid invasion, Britain and France triggered the next phase of the plan on November 5 and 6, invading Port Said and Port Fuad and bombing Egypt's grounded air force.

Britain's invasion was swiftly condemned by the United Nations, the United States, and the Soviet Union. When the UN threatened sanctions, economic panic set in, causing tens of millions of pounds to be lost from Britain's reserves. This was compounded when President Eisenhower pressured the International Monetary Fund to deny Britain financial assistance (via Imperial War Museum). There was nothing that Britain could do but withdraw. It was a stark reminder that the age of empire was over.