The Messed-Up Truth About The 1950s Film Industry

The Golden Age of Hollywood was not so golden. Despite the Paramount ruling of 1948, which forced the studios the separate themselves from their theater holdings (via History), the major studios still had a disproportionate amount of power over their stars. While the Golden Age of Hollywood produced amazing films, the stars were in a position of weakness — since the studios held the contracts, and therefore the control over the money, callous studio heads could treat the actors and actresses under contract with impunity.

There were few consequences to treating actors like property, so while on the surface everything dazzled and gleamed, the underside of Hollywood in the 1950s was a dark one. Censorship and discrimination paraded as morality, and all too often the people who worked hard to conjure dreams ended up with shattered dreams themselves. Hollywood didn't care who was hurt, or terrorized, as long as the money kept flowing. Here's the messed-Up truth about the 1950s film industry.

Censorship was the rule of the day rather than the exception

While Billy Wilder was writing the screenplay for "Sunset Boulevard," he feared censorship and studio interference so much that he told the studio he was adapting a short story that didn't exist, and only submitted a few pages at a time — when they began filming, the script was not completely finished, so no one knew how it would end.

According to the Writer's Guild of America, the script was called "A Can of Beans" to hide the subversive, anti-Hollywood nature of the project from the studio, in part because the screenwriters (Wilder and Charles Brackett, with help from D.M. Marshman Jr.) were afraid the project would get canned or scuttled if its true nature came out. Since Wilder had come to America to escape the Nazis, having lost family to Auschwitz, he knew all too well about oppression and censorship and saw something to be afraid of in the enforced morality of the Hays code, which specified certain issues as immoral and off-limits for film.

The Hays code, per NPR, was a set of guidelines designed to avert emotional outrage, and it specified which topics were off-limits and which had to be handled with a particularly moral kind of care (called "Don'ts and Be Carefuls"). Its influence was felt in Hollywood from 1930 until 1968, when the Motion Picture Association adopted the ratings system moviegoers are more familiar with today.

Homosexuality was forbidden

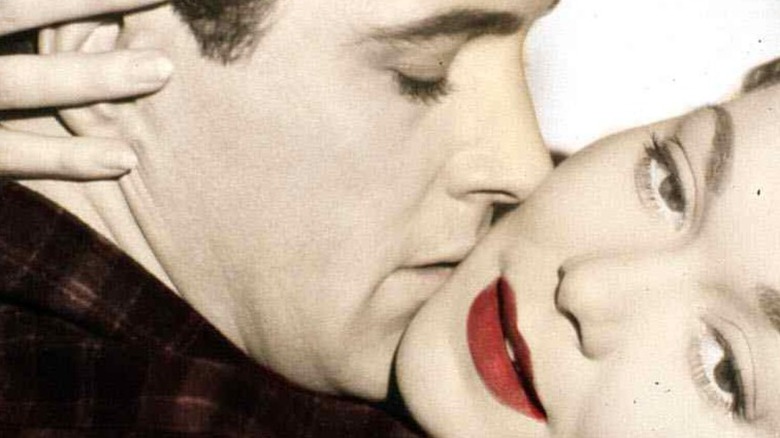

Movie stars were expected to maintain a certain image, both physically and socially, and the studios were ruthless in enforcing it, so that anyone who did not fit their expected image received poor treatment. Homosexuality was taboo, so much so that Rock Hudson was forced into a sham marriage in 1950 so as to appear heterosexual.

The marriage was largely a surprise, when, shortly before his 30th birthday, reported the Los Angeles Times, he married Phyllis Gates, who worked as his agent's secretary. Hudson, who later revealed his AIDS diagnosis and turned the conversation about AIDS and HIV in 1985 into a national one, had been linked to male stars in Hollywood, and the marriage was not a successful one, as they divorced three years later, notes People.

Later reporting in a biography by Mark Griffin (via USA Today) confirmed that the marriage was just for show. Persistent rumors of homosexuality or bisexuality attached themselves to several other notable stars of the period — Talulah Bankhead, Marlene Dietrich, and Great Garbo were frequently mentioned in such a context, as per "The Girls," by Diana McLellan (via the New York Times). But those labels would have been career death if confirmed, so while the stars did as they wished behind closed doors, no hint of homosexuality was allowed to creep into the public eye.

Freedom only applied to some

In 1950, the freedoms of the Civil Rights movement were years away. America was still very much a segregated society, and actors and actresses of color were treated poorly, denied equal rights, and often forced into lesser roles. Hollywood whitewashed scripts, so a variety of non-white roles were played by white actors. Orson Welles played Othello in blackface in 1955, and in 1950's "Winchester '73," Rock Hudson played a Native American.

Blackface had been a feature of Hollywood productions for decades prior, going back to Al Jolson in 1927's "The Jazz Singer," but increasing racial tensions in the 1950s made the whitewashing of roles much more troublesome and contentious. Ava Gardner, a white woman, played a lighter-skinned mixed-race character who was passing as white in "Show Boat" (1951), and according to the Washington Post she was given the job over Lena Horne, who was actually of mixed descent, because the studio was afraid of how audiences would receive her love scenes — interracial marriage was still very much taboo and illegal in many states, so there was some question of whether they could show Horne in romantic situations.

Because Black actors still had little recourse, leverage, or social agency, roles that were originally written for characters of color were regularly renamed or recast to feature white actors instead.

Typecast, if cast at all

When they were cast, Black actors and actresses were often given lesser roles, or demeaning ones, and little recognition. The Black vaudeville circuit, where many Black performers got their start, was hard work for little pay, largely catering to old minstrel stereotypes and a point of some argument within the Black community. Hattie McDaniel, who had a career in vaudeville and later worked at Sam Pick's nightclub as a singer before coming to Hollywood, according to Britannica, won an Oscar for her role in "Gone With The Wind" in 1940 but didn't get many opportunities to play anything besides a maid or a servant for much of her career.

In fact, at the Oscars that evening, McDaniel was seated apart from the rest of the audience. She's quoted as saying (via Vanity Fair), "I can be a maid for $7 a week. Or I can play a maid for $700 a week" in Jill Watts' biography of McDaniel. She wasn't allowed to attend the film's premier in 1939, and by the 1950s the situation hadn't improved to any noticeable degree. Black actors and actresses were still relegated to largely supporting roles, with a few exceptions. Dorothy Dandridge, for example, was nominated for Best Actress in 1954 but had little success in Hollywood after, as per Britannica.

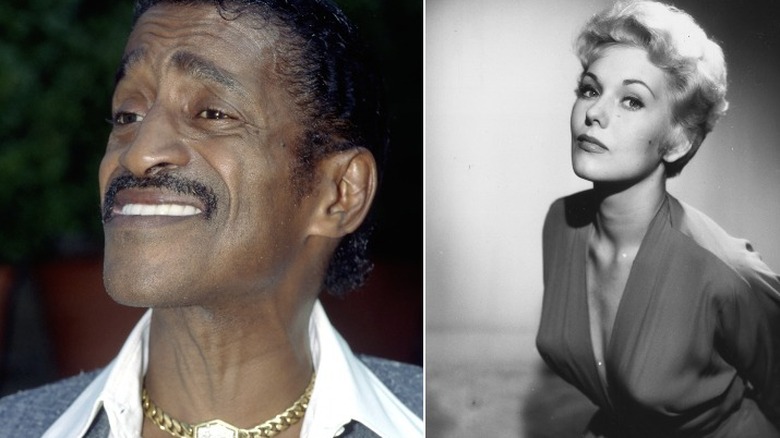

Actors were not allowed to date across color lines, either

When movie star Kim Novak was discovered to be in a relationship with Sammy Davis Jr., studio head Harry Cohn stepped in, leveraging his mob connections, and intimidated Davis into breaking it off.

Interracial marriage wasn't legal until 1967, so when the two were romantically linked by a gossip columnist in 1957, it meant big trouble. Davis had been linked romantically to several of the leading ladies of Hollywood, but Cohn, who had taken great pains to develop Novak into a big-studio bombshell, saw the actress as his own personal project. He was infuriated, even, according to Vanity Fair, suffering a mild heart attack on the plane to Los Angeles. Since Novak's relationship with Davis would jeopardize her status as a sex symbol and potentially cost the studios a great deal of money in lost profits, Cohn (already notorious for his temper) called in those shady mob connections, who threatened to end Davis' life. According to Arthur Silber, a friend of Davis, in an article in the Smithsonian magazine, "They said they would break both of his legs, put out his other eye, and bury him in a hole if he didn't marry a black woman right away." Davis and Novak broke it off, and he did indeed get married a year later.

The Mob also had its hand in many other aspects of the business

Harry Cohn, the hot-tempered studio boss, had mob connections (per The Guardian) and some link to gangster Mickey Cohen, and this was far from a single instance of organized crime being entangled with Hollywood — most studios employed "fixers," men whose job it was to make embarrassing problems disappear, whether that was the unplanned pregnancy of an actress or the misbehavior of a star.

George Reeves was found dead on June 16, 1959, and the New York Times reported it as an apparent suicide. As noted in the Los Angeles Times, his fiancée Lenore Lemmon said he was going to his room to kill himself shortly before any of his guests heard the shots, only one of several suspicious details. According to reporting in Wired, he'd recently broken off an affair with Toni Mannix, the wife of Eddie Mannix, a well-known fixer. Mannix's other contribution to Hollywood history was a ledger in which he recorded costs and profits for studio films, presumably for some dubious end — the ledger is now used by film historians as an invaluable insight into the often-murky or undisclosed internal finances of the big studios.

While Reeves death was ruled a suicide, there were several irregularities about the crime scene, enough to cast doubt. Eddie Mannix's reputation, and Reeves' recently ended entanglement with Toni Mannix, were enough to create the strong suspicion that Eddie had something to do with Reeves' death, suspicions that linger to this day.

The House Un-American Activities Committee ruined lives and careers

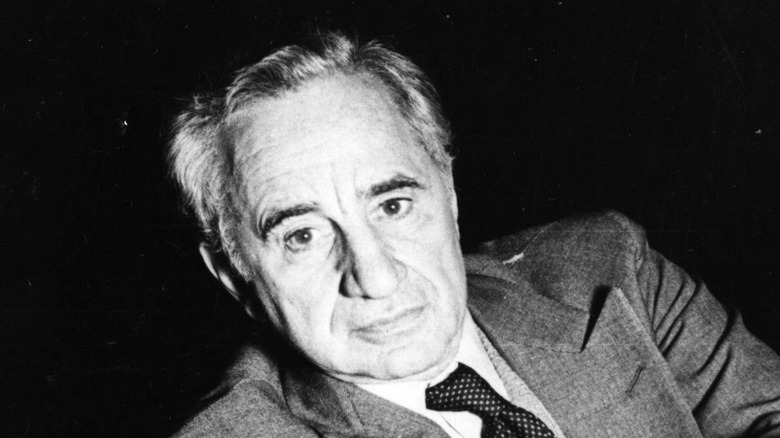

The classic "On the Waterfront" (1954) had strong parallels to director Elia Kazan's own experiences testifying in from of the House Un-American Activities Committee, a group House representatives tasked with investigating communist allegations, according to History. Britannica notes that industry professionals were often subpoenaed as the committee began its investigation into Hollywood.

When Kazan was brought before the committee in 1952, unlike most of the people questioned, he did name names, a fact that Hollywood never forgot and only partially forgave. Interviewed in 1988 for NPR, Kazan said of his testimony, "I thought very hard about it. And I did — I made a difficult choice. Both sides, both ways would have been difficult for me."

Kazan had a complex relationship to art and to censorship and downplayed the impact his testimony might have had, but he was also quoted in a French interview in 1962 as saying," You don't want to have dinner with a monster. But in art, it's necessary to be a monster, in part, to have very strong feelings ..." While the script for "On The Waterfront" deals with longshoremen in Hoboken, it also deals with mob interference and political betrayal, so it's not much of a stretch to conclude that the betrayals in the film had a more personal resonance for Kazan, given his testimony, as the Los Angeles Times notes.

Actors and writers attempted to protest against the Red Scare but had to do so indirectly

During the 1950s, actors and writers were afraid of censure, or prosecution, possibly both. Fearful of consequences, as Britannica notes, actors, filmmakers, and other industry professionals could find themselves on a blacklist compiled by the studios in order to avoid any backlash from employing talent with potential communist ties. The film "High Noon," which earned Gary Cooper an Oscar, was written in response to the HUAC and McCarthyism by Jewish screenwriter Carl Foreman, who was blacklisted by Hollywood for inadequate cooperation. He lost his associate producer credit as a result.

Foreman, who had joined the Communist Party in 1938 with his wife and quit in 1943, was brought before the committee and pleaded the Fifth Amendment to avoid admitting to his membership prior to 1950 (via Vanity Fair). He was deemed uncooperative, and the next day Columbia began negotiations for his severance. He kept his screenwriting credit, but according to Glen Frankel in an NPR interview in 2018, the loss of his producer's credit meant that "he really lost his control over the film and for all intents and purposes, that was the end of his Hollywood career." Foreman left America for England, where the professional and emotional impact of his blacklist lingered for much of the rest of his working life.

A vicious double standard

Women were expected to maintain a certain studio-approved persona in both their public and private lives, a standard men were not held to as closely. Ingrid Bergman, who had an affair with Roberto Rosselini while she was married, had a baby out of wedlock in 1950, and was ostracized by Hollywood afterwards.

Bergman became interested in Rosselini after seeing two of his films, and according to the New Yorker, she wrote him offering to act for him. She went to Italy to work with him on the film "Stromboli" in 1950. At the time she was married to Peter Lindström, and the two had a daughter, but she fell in love with Rosselini and moved in with him. She was pregnant with his child before her divorce from Lindström was finalized, and this scandal prompted outcry and outrage in America.

Bergman was pilloried in the press, and there were calls for a boycott of her works (per the New York Times). While she didn't intend to return to Hollywood, since she was enamored of Rosselini, who didn't want her to work with anyone else, the damage to her career was not insignificant. Much of her work following was with Rosselini, and as her daughter, Isabella, said in a Newsweek interview, "Mother spoke five languages and had a full career in English, a full career in Swedish, a full career in French and German, which is very unusual." Clearly, her career path would have been quite different without the moral outrage of America that led her to turn her back on Hollywood.

Pregnancy was out of the question

Women were also not allowed to become pregnant, since it would jeopardize their image in the public's eye. Many actresses who became pregnant were forced by the studios to have abortions.

According to conventional wisdom of the time — the male-dominated studio heads, who had clauses banning pregnancy written into their contracts (via Vanity Fair, ) — a woman couldn't be a sex symbol and a mother at the same time, which forced many actresses to choose between having a child or having a career, since they couldn't have both. The fact that abortion was illegal and dangerous was a lesser concern than any potential damage to their reputation or earning potential.

Abortions were commonplace even before the 1950s, and stars like Judy Garland, Lana Turner, and Joan Crawford were only a few women said to have had abortions that were kept secret from the public — while the men of the day were free to sleep with whomever they might please, and often the women they became involved with had to suffer for their passions. Howard Strickling, who was a "fixer" like Eddie Mannix, was reported to have arranged more than a few.

According to Vanity Fair, when Dorothy Dandridge became pregnant in 1955 by Otto Preminger, her director in "Carmen Jones" who was also white, her situation was doubly damning. Preminger refused to leave his wife, and the studio forced Dandridge into terminating her pregnancy because the child would be mixed-race.

Young actresses often dated beyond their years

Speaking of the Hollywood double standard, women were often involved with men many years their senior. For example, according to the Baltimore Sun, while filming the James Dean classic "Rebel Without A Cause," Natalie Wood reportedly had an affair with the director, Nicholas Ray. Natalie Wood was 16 at the time, while Ray was 43. While this would raise eyebrows today, there were no consequences of this relationship at the time, despite the statutory rape laws on the books in California stating that their age difference should have resulted in charges.

Wood had a less-than-perfect home life before being drawn into Hollywood. As reported by Vanity Fair, biographer Suzanne Finstad in her book "Natalie Wood: The Complete Biography" said she was possibly forced into a relationship with Frank Sinatra at 15 and reportedly began a relationship with Ray for her role in "Rebel Without a Cause." The California Penal Code defined a minor as someone under the age of 18 and specifies that sex with minor three or more years younger than the perpetrator may face a misdemeanor or a felony — clearly the difference in their ages was significant enough to qualify. The relationship fell apart, and Wood moved on to a relationship with Robert Wagner, marrying him in 1958.

When do I get paid?

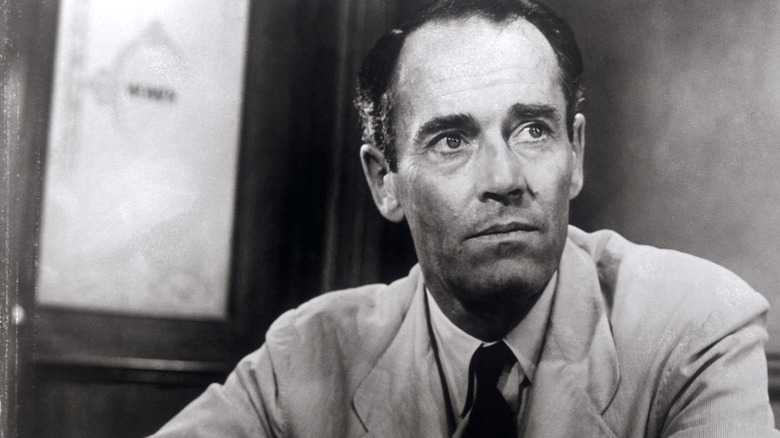

Despite making money for the studios, actors and actresses made little money themselves — and in a few cases didn't get paid at all. When the 1957 classic film "12 Angry Men" was released, star Henry Fonda (also a co-producer) didn't see a paycheck.

Produced on a small budget by Hollywood standards of $340,000, "12 Angry Men" received good reviews but wasn't immediately very profitable (per Britannica). Fonda and producer Reginald Rose had deferred their salaries and didn't receive even half of their pay. Fonda remained critical of the role the studios played in the film's modest success, and in his autobiography blamed United Artists for failing to properly support the film — for example, not rereleasing the film after it was nominated for three Academy Awards, according the American Film Institute.

The movie took awards from the British Film Academy, the Polish Film Critics Association, and the Berlin Film Festival. While "12 Angry Men" went on to earn far more money and garner more critical acclaim (per Library of Congress), the film wasn't particularly successful in its initial release, largely due to United Artists failure to really believe in its potential. The studio undercut the film, and Fonda's paycheck suffered as a result.