The 1,800-Year-Old History Of Science Fiction Explained

When asked to think of "science fiction," many folks might reflexively blurt "Star" followed by "Trek" or "Wars." If they know their stuff, they might cite time-honored authors like Isaac Asimov, Frank Herbert, Philip K. Dick, or newer writers like Iain M. Banks, Liu Cixin, and Ramez Naam. If they're a classicist, they might go back to 19th-century sci-fi titans H.G Wells and Jules Verne. Probably very few people would associate sci-fi with the temples, wine-drinking, and proto-democracies of Ancient Greece. After all, natural philosophy didn't even begin to evolve into recognizable, evidence-and-hypothesis-based "science" until the mid-1700s (as Slate summarizes).

But yes, science fiction does indeed go back to the 2nd century CE. That doesn't mean that ancient sci-fi features cell phones, rocket propulsion, and quantum tunneling. Rather, it means that the recognizably current sci-fi tropes — extraplanetary adventure, alien races, space flight, and the rest — were present even back then, albeit in a softer, more fantastical form.

Some say that the difference between sci-fi and fantasy is that sci-fi is possible, but fantasy isn't. But the further back we go, the less "hard" sci-fi gets — focused on serious science and believable scenarios — and the more it resembles nebulous, hybrid genres like speculation and slipstream fiction. For the sake of this article, we're going to adopt the broader definition of science fiction as "fiction centered on the resolution of dilemmas derived from human social and technological progress."

Space battles, flea-archers, and Alexander the Great

Science fiction's first extant tale comes from Lucian of Samosta, an Assyrian living in what's now modern-day, southeast Turkey, who wrote "Verae Historiae" ("True Histories") in Greek. The work, neither true nor history, remains one of the most bananas, over-the-top pieces of satire ever written.

Lucian, as Ancient World Magazines explains, wrote "Verae Historiae" to lampoon the popular travelogue genre of the day: accounts written by explorers reporting on their journeys. We're talking "I killed 100 giants with a rock!" when in fact someone stubbed their toe on a rock and screamed in terror at a lizard. In the forward to "Verae Historiae" Lucian wrote that his pages "parody the cock-and-bull stories of ancient poets, historians, and philosophers," and were written independent of "any verisimilitude in the piling up of fictions."

The heroes of Lucian's tale start like many tales of the time, with a ship setting off on a "Jason and the Argonauts"-like ship-bound journey. From there, they get snared by a whirlwind that takes them to the moon, and get caught in a giant interplanetary war between the moon people and sun people who both want to conquer "the Morning Star" (i.e. the planet Venus). Their armies contain "horse-ants, garlic-men, flea-archers, stalk-fungi, ostrich-slingers, 'dog-faced men fighting on winged acorns,' cloud-centaurs, armor made from beans," and more. The adventurers eventually get swallowed by a giant whale, meet (because why not) Alexander the Great and Homer, and on and on the lunacy continues.

Atlantis, the Dragon Palace, and Lilliputians

Before we get into ostensibly "technological" science fiction, we should take a snapshot of the centuries between "Verae Historiae" and the 1800s' pre-modern sci-fi circa the advent of the Industrial Revolution. Practically anything fantastical that places a premium on imagination and inventiveness, unfathomable entities and situations, problem solving and moral dilemmas, and considers not only human past, but its potential and future, took a hand in prefiguring what we currently recognize as "science fiction."

The ancient legend of Atlantis features a very modern-sounding cautionary tale of an ancient, super-advanced civilization that obliterated itself for some reason or another. Talk of Atlantis was circulating for hundreds of years even by Plato's time in the 5th century BCE (via History), and resurfaced in popular discussion during the 17th century.

Other examples include the Japanese time-traveling tale "Urashimo Taro" from the 8th century CE, which features a Good Samaritan-like child who experiences a Rip Van Winkle-like time-lapse after returning to his village from visiting the Dragon Palace on the back of a turtle (via Japan Info). We've also got the astounding stories of adventure, genies, and kings compiled in "The Arabian Nights," which date back to the 7th to 10th century CE in modern-day Iran, Saudi Arabia, and India (via Annenberg Learner), and were translated into English in the early 1700s. And in 1726, Irish satirist Jonathan Swift wrote Gulliver's travels about a dystopian community of tiny, useless little scientists, the Lilliputians.

From Frankenstein to the Eloi

We owe the kickoff of modern science fiction to Mary Shelley, author of "Frankenstein" (1818). The word "Frankenstein" has become shorthand for any kind of monstrous, grotesque creation built from shortsightedness, hubris, and more than a bit of scientific folly. That central idea has come to typify science fiction's central debates as they reflect ever more rapid technological and societal progress. Namely: If we can, should we? If we do, what are the consequences? Are we losing something fundamental and irrecoverable? Will we ourselves transform into inhuman monsters, whatever "human" means? Do we, like Frankenstein's monster, deserve to live if our handiwork produces not only untold insights, but untold suffering?

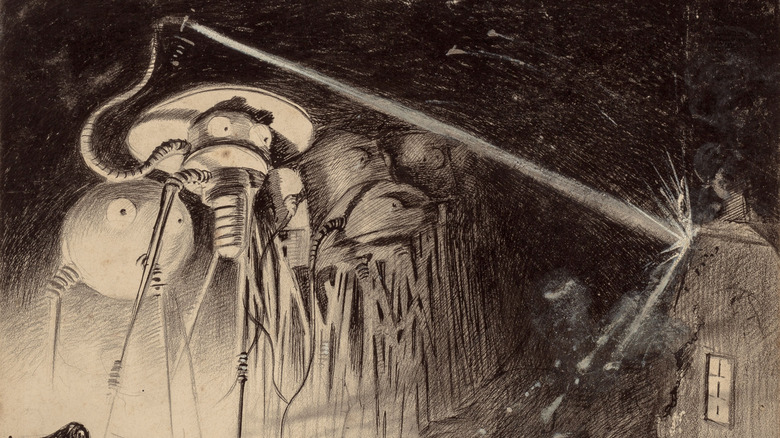

Shelley wrote Frankenstein toward the tail end of the Enlightenment, an historical shift in human consciousness away from reliance on religious texts for truth and toward scientific empiricism (as History summaries). As the Industrial Revolution reached full steam during the reign of Queen Victoria, machines replaced fields, and the soot of smokestacks replaced the dust of Earth. Authors who sensed the zeitgeist tackled it from different angles. Jules Verne, one of sci-fi's grandfathers, penned rousing, techy adventures (echoing Lucian of Samosta's 2nd-century work) such as "Journey to the Center of the Earth" (1864) and "Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea" (1870). Sci-fi's other, younger grandfather, H.G. Wells, took the Cassandra approach, warning people of the dangers of things like technological dehumanization ("The Time Machine," 1895) and extraterrestrial life ("War of the Worlds," 1897).

Pulp, psychedelia, and the space race

Sci-fi took off in the 20th century as humanity became decidedly more dependent on, and interwoven with, technological devices. The Wright Brothers' first flight (1903), the mechanized slaughter of World War I (1914-1918), the space race of the 1950s and '60s, the digital era. an internet-based society: all of these advancements reflect in sci-fi's evolution.

"Metropolis" (1929) translated sci-fi into film for the first time, in a mind-blowing masterpiece critiquing the oppression of a mechanized humanity (the whole thing is available on YouTube). The 1920s through 1940s saw sci-fi settle into pulpy, by-the-word short stories like those in the magazine "Amazing Tales" (via Pulp Mags). Meanwhile, heavy-hitting, serious-minded authors like Isaac Asimov (1920-1992) focused on the consequences of artificial intelligence, Arthur C. Clarke (1917-2008) on space travel, and Robert Heinlein (1907-1988) on technology's sociopolitical fallout. Philip K. Dick (1928-1982) brought us disturbingly modern man-in-the-machine tales influenced by 1960s counterculture and psychedelia, while authors like Frank Herbert (1920-1986) drew from the same bedrock to discuss human destiny as related not to outward space, but inward enlightenment. The former authors would be categorized more as "hard" sci-fi, the latter as "soft" sci-fi.

Along the way, sci-fi saw a cross-media explosion through TV shows like "Star Trek" and movies like "Planet of the Apes" (1968), "2001: A Space Odyssey" (1968), and eventually blockbusters like "Star Wars" (1977).

Digital minds, dystopian futures, and loads of rehashes

At present, sci-fi is absolutely everywhere in literature, movies, TV, games, and much more, to the point where it's hard to imagine modern culture without its critique. In short, current sci-fi focuses heavily on everything "digital," which isn't surprising because modern life is practically defined by the internet. We're talking reflections of fear and paranoia about social media, depersonalization and alienation, the pitfalls and deceptions of digital personas, and so on. Take this and combine it with some throwback space colonization forays like "The Expanse" (2015-2022), and lots — repeat: lots — of remakes, redoes, rehashes, and reboots of older work, and you've got a good snapshot of sci-fi as its evolved over the past 40 or so years.

While it's hard to find an exact cut-off for when the "modern" era of sci-fi began, we could make a worse choice than William Gibson, born in 1948. As Vice discusses, his "Neuromancer" (published in 1984) created nearly every dystopian, cyberpunk convention you can think of: a highly stratified, oppressed futuristic society; Frankenstein-like cybernetics; consciousnesses removals and uploads; everything. "Black Mirror" (2011-2019), "Altered Carbon" (2018-2020), "Upload" (2020-present), and so many more all reflect his particular strain of sci-fi.

As always, art is arguably the best barometer of the times, which makes current dystopian and cyberpunk preoccupations rather telling. This is why sci-fi doesn't just represent a forecast of our possible futures, but a chronicle of our past and present, as well.