The Tragic Story Of The Clinton Avenue 5

On a summer evening in Newark, New Jersey, five Black teenagers went missing in 1978, never to be seen or heard from ever again. Their bodies were never found, they never contacted their families, and no one has any idea what happened to them. Despite the incredibly unusual nature of the case — it's rare for a group of people to go missing and never be seen again, compared to an individual — there's little information available about the event. Most of the information about the Clinton Avenue Five came out over 30 years after the boys first disappeared.

But while the police insisted that they finally had the right perpetrators more than 30 years after the crime was committed, there was little physical evidence tying their case together, leading some to wonder whether or not the police were simply interested in tying up the case with a neat little bow. Some have even suggested that the arrest they made was all just part of an elaborate scheme to gain political points.

But at the end of the day, it's the families of the five boys that are left in limbo, unable to lay to rest the remains of their loved ones and never knowing for certain exactly what happened to them. Even in the court of law, justice has been elusive and uncertain. This is the tragic story of the Clinton Avenue 5.

Newark in the '70s

In the 1970s, the city of Newark, New Jersey struggled as the economy floundered and crime rates rose. While violent crime rates had risen across the United States by 25%, Brad R. Tuttle writes in "How Newark Became Newark" that in that city, violent crime rates rose 91%. Some who could afford to leave left the city and between 1960 and 1990, Newark lost more than 125,000 people, representing a third of its population.

In the 1970s, Newark was also filled with abandoned buildings, as many businesses shuttered and people lost their homes. Many of them would end up catching fire, according to CNN. In 1978 alone, there were over 2,600 conflagrations in abandoned buildings.

Newark's "free fall" was described by journalists as "a classic example of urban disaster" and "a study in the evils, tensions, and frustrations that beset the central cities of America." In 1975, it was even given the title of "The Worst American City" by Harper's.

Who were the Clinton Avenue 5?

The name Clinton Avenue 5 refers to Melvin Pittman, Ernest Taylor, Alvin Turner, Randy Johnson, and Michael McDowell; five Black teenagers who all disappeared from Newark, New Jersey on August 20, 1978. They were aged 16 and 17 years old and on this particular summer's day, they were all reportedly playing basketball together in West Side Park. All five had grown up in Newark, but McDowell had recently moved to East Orange, according to ABC.

The New York Times reports that after their basketball game, the boys decided to split up and head home for some dinner before heading out to meet up again. According to Trace Evidence, the boys reportedly already had plans for the evening to help local business owner Lee Evans move boxes. But the evening would still be young when they were finished and they didn't have any other set plans for the night.

However, no one knows if they ever made it to see the rest of the night. Although some of the boys were later seen on or near Clinton Avenue, the last sighting was around 11 PM. After that, none of the boys were ever seen or heard from again.

The disappearance

There were sporadic sightings of some of the boys on the night of August 20, 1978. The New York Times reports that Randy Johnson was last seen walking down Fabyan Place around 7 PM. Meanwhile, Melvin Pittman was last seen walking by an ice cream parlor on the same street a short time after dusk. Ernest Taylor, Alvin Turner, and Michael McDowell were all seen riding down Clinton Avenue in the back of a pickup truck driven by local carpenter Lee Evans. It's believed that all five may have helped Evans unload boxes from his truck, and ABC reports that Evans often hired teenagers to assist him with random work. Afterwards, the three seen in the truck were seen near Fabyan Place around 11 PM. This is the last known sighting of any of the boys.

Evans claimed that he dropped the boys off around 11 PM. However, although Evans was initially considered a suspect in the boys' disappearance, police dismissed their suspicions after Evans passed at least one lie-detector test, according to NJ.com.

Who was Lee Evans?

Lee Evans was a local carpenter and contractor in Newark when the Clinton Avenue 5 disappeared and would've been in his 20s at the time. CNN also reports that at the time, Evans was known by the nickname "Big Man." According to ABC, Evans was considered to be a prime suspect after the boys' disappearance and was interviewed repeatedly after the Clinton Avenue 5 disappeared.

Evans was the last person seen with the boys, but he repeatedly insisted that after the boys had finished working for him moving boxes, he'd dropped them off on a street corner near an ice cream parlor on Fabyan Place near Clinton Avenue. After he passed a polygraph examination, Evans was dismissed as a suspect.

However, many still remained suspicious of Lee Evans. Floria McDonald, the mother of Turner, stated that when she confronted him about her missing son, he was "kind of smart and nasty."

A prank call

Initially, police believed that all five of the boys ran away and some reports state that the boys were only reported missing a few days after their initial disappearance. But according to The Charley Project, all of the boys' family members insisted that there was nothing to suggest that the boys had any intention of running away. And a few days after the boys disappeared, one of their mothers received a phone call from someone who claimed that "he knew their whereabouts and would tell her for $750."

Police investigated the phone call and traced it back to a payphone in Washington, D.C. at Union Station, but by the time police arrived there was no one at the scene. It's unclear whether or not the caller was even genuine. Another caller claimed that the boys were in jail in Washington, D.C., and offered to put up $150 bail for the boys, but police reportedly decided that the call was a prank, reports NJ.com.

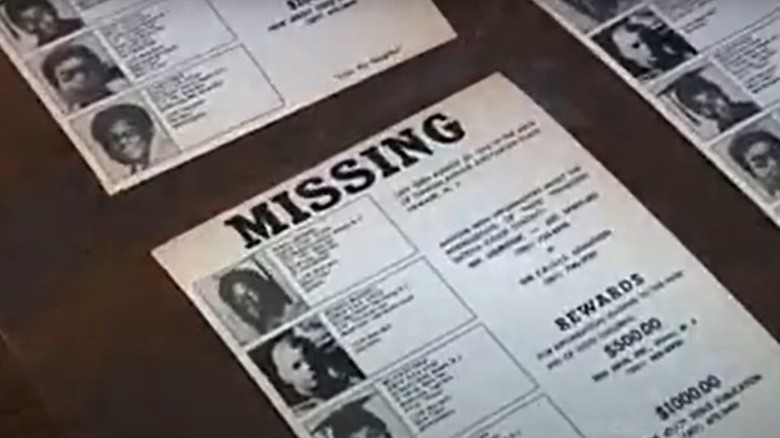

Looking for the boys

After the boys' disappearance, police exhausted numerous options after they eliminated their top suspect. The New York Times reports that in the weeks following, police interviewed "hundreds of people," dragged rivers, and sent missing-persons fliers across the country. Some family members of the boys also eventually submitted their DNA to be cross-referenced with bodies in morgues, but nothing ever came up. According to NJ.com, police also cross-checked with the list of victims in Jonestown, Guyana and the Wayne William serial killings in Atlanta, but they repeatedly failed to turn up any sign of the five boys.

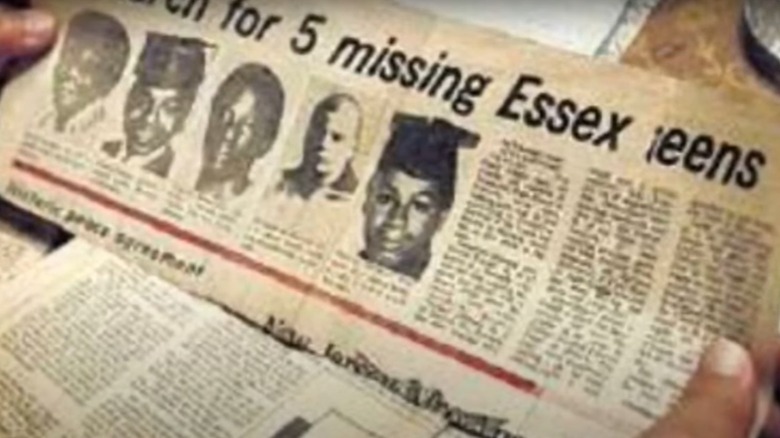

And despite these reports of a nationwide search, there are surprisingly few media reports about the disappearance. Crime reporter James Queally notes in Crime Reads that almost all of the articles written about the Clinton Avenue 5 seem to be written after Lee Evans' arrest in 2010. Queally notes that this is especially surprising because "Vanishings are catnip to reporters."

Over the years, police investigators chased numerous dead-end leads, and "at least two psychics" were enlisted by the police to help with the search, writes The Seattle Times. According to Robert Laurino, acting prosecutor of Essex County, the boys "essentially disappeared off the face of the earth," per the Los Angeles Times. For 30 years, there was no trace or news of the whereabouts of the Clinton Avenue 5 other than the occasional psychic claiming to have information.

30 years later

In 2008, there was a sudden development in the case. The New York Times reports that Philander Hampton, a man who was imprisoned at the time, confessed "to helping his cousin, Mr. [Lee] Evans, lure the boys to an abandoned house on Camden Street," where they were subsequently murdered. Hampton claimed that he thought the whole thing was part of a prank "that would end at any minute." But instead, he claimed that he ended up watching as Lee Evans forced the teenagers into a closet, nailed it shut, poured gasoline around the house, and asked Hampton for a match. Hampton later testified that he didn't see Evans light the match, but he saw the house go up in flames and collapse.

Although police tried to corroborate this story, if the building burned down 30 years ago, it meant that much of the physical evidence that may have been there would have been lost. The Charley Project writes that the fire also reportedly spread to its neighboring houses as well. According to CNN, Newark firefighters in the 1970s often let abandoned buildings burn.

When initially questioned, Evans insisted that he had dropped the boys off near the ice cream parlor near Clinton Avenue, The Seattle Times reports. But Hampton now claimed that Evans had murdered the boys in retaliation for stealing his cannabis. Police ended up searching the area of the former Camden Street residence, but using "ground-penetrating radar," they reportedly found no evidence of human remains.

Arresting Lee Evans and Philander Hampton

Based on Philander Hampton's confession, which he described as "13 hours of questioning by the police," Lee Evans was arrested and the two men were charged with murder and arson in March 2010. Los Angeles Times reports that although the police maintained that Hampton's confession was legitimate and trustworthy, they admitted that they hadn't found the remains, "something that cold-case expert Joseph Pollini said makes the case highly unusual." And as of 2022, the five bodies have not been discovered. According to The Seattle Times, Ernest Taylor's brother told reporters that 18 months prior to the arrest, Evans had confessed to him as well. After he'd informed the police, they'd been working on corroborating this alleged confession as well as the confession provided by Hampton.

NJ.com reports that while the bail for both men was set at $5 million, Evans' bail was reduced by Superior Court Judge Peter Vazquez to $950,000, citing "Evans' strong ties to the community, his lack of a criminal record, and the prosecution's difficult case as reasons." The arson charge was also seemingly dropped before going to trial.

There was also reportedly a third suspect in the disappearance of the Clinton Avenue 5, Maurice Woody-Olds, who was another cousin of Lee Evans, but The Charley Project writes that Woody-Olds reportedly died of natural causes in 2008.

A chance survivor

After Lee Evans was arrested, one man realized that he and his brother may have narrowly avoided the fate of the Clinton Avenue 5 over 30 years earlier. CNN reports that Roderick Royster and his brother were part of the group of boys that got together at Evans' pickup truck but it was only by chance that they didn't end up going with the rest of the boys. Royster was 16 at the time, and although both he and his brother were already in the truck, Royster's father reportedly came out and told them to get off the truck and go back home.

During the trial, Royster testified as a witness that his father stated a bit more explicitly, "You better get off that truck or you're going to wake up and find yourself dead." NJ.com reports that Royster also testified that Michael McDowell reportedly gave him two ounces of cannabis just hours before his disappearance. "He told me he had 7 pounds of weed. Michael said he stole it but didn't say who from."

Royster told reporters during the trial that he "always knew" who was responsible and that after so many years, he was looking forward to "get[ting] some closure."

Philander Hampton pleads guilty

In 2011, Philander Hampton pled guilty to five counts of felony murder. And The New York Times reports that part of his plea agreement involved testifying at Lee Evans' trial. The plea agreement also included a 10-year sentence and a charge of $15,000 to be paid for his relocation upon release, writes 54 History, since Hampton was going to be placed in witness protection for a limited amount of time.

During the trial against Evans, Hampton testified that the memory of the event had been "wearing him down," but when cross-examined by Olubukola Adetula, who was assigned to assist Evans, Hampton answered affirmatively as to whether or not "the name Evans was the name that was going to get you out, right?" Lehigh Valley Live reports that the prosecution's case "largely hinged" on Hampton's testimony, since little physical evidence was recovered, and so during the trial, Hampton reiterated the confession he'd previously given to police. New Jersey 101.5 writes that although many people didn't believe Hampton's story, no other alternate theories were presented.

Philander Hampton was released from imprisonment in 2017.

Acquitting Lee Evans

Lee Evans ended up representing himself at his trial in November 2011, though attorney Olubukola Adetula was assigned to assist him, claiming that he was dissatisfied with his court-appointed attorney. At a court hearing, Evans stated that "The defense is not in my best interest. Since March 2010, when I was arrested, neither one of the attorneys has asked me if I was innocent."

However, Amsterdam News reports that Evans was unprepared for his defense and "couldn't answer basic questions about the case." In total, there were up to 20 witnesses that testified against Evans, but NJ.com writes that Evans let slip several opportunities "to hammer away at a witness' credibility."

After less than a month at trial, The New York Times reports that Lee Evans was acquitted of all the murder charges. Charged with five counts of felony murder and five counts of murder, Evans was charged twice for each victim and received 10 recitations of "not guilty."

Lee Evans sues

In November 2013, Lee Evans filed a civil suit against the City of Newark, Essex County Prosecutor's Office (EPCO), the Newark Police Department, and then-Mayor Cory Booker. According to Evans v. City of Newark, Evans stated that prosecutors from the EPCO submitted the murder case to a grand jury three times "within a five-month period" and were only able to obtain an indictment on the third try. Evans also alleged that evidence was misrepresented to the grand jurors and that exculpatory evidence was withheld from them. Evans also claimed that Mayor Booker and former Newark Police Director Garry McCarthy were responsible for "vilif[ying]" Evans in the press.

Evans claimed not only malicious prosecution, but he also claimed that the defendants "civilly conspired to deprive Evans of his constitutional rights under 42 U.S.C. § 1983." Evans based this on the fact that his arrest occurred three weeks before a local election, and so he claimed that his arrest and the settlement of the cold case "were allegedly motivated by [Essex County Prosecutor Robert D. Laurino's] desire to aid Mayor Booker's campaign and obtain career advancement."

However, some of the counts in the case were dismissed "because the State and employees sued in their official capacities are not 'persons' amenable to suit under § 1983 or the NJCRA [New Jersey Civil Rights Act]." The counts against the City of Newark, Booker, and McCarthy remain and according to Court Listener, the lawsuit remains ongoing as of February 2022.