How The Gilded Age Got Its Name

After the end of the Civil War, Americans were promised an era of progress and prosperity — a "Golden Age." In "The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today," an 1873 satirical novel by Mark Twain and Charles Dudley Warner (via Bookero), one character waxes poetically: "Who shall say that this is not the golden age ... of unlimited reliance upon human promises?" The novel, satirizing the era's corruption and materials, quipped that this was not a "Golden Age," but a "Gilded" one.

Much like gilding — a thin veneer of gold overlay applied to wood, metal, or ceramic to conceal the original material — the era's fixation on overly opulent displays of wealth masked the far less-dazzling reality of Gilded Age life.

The Gilded Age spanned from roughly 1870 to 1900. According to others, it kicked off when the Civil War ended, then dissolved into the Progressive Era at the turn of the 20th century. The term "Gilded Age" originated with Twain and Warner's 1873 novel, but it entered the lexicon in the 1920s or 1930s as a means of referring to the epoch of corruption and extravagance in late 19th century American history. The earliest known use of the term to refer to this epoch was in a chapter heading by Charles Beard, according to Neil Harris in "The Gilded Age Reconsidered Once Again."

The Beginning

The Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1914, via History) was underway and the United States soon became a fully-fledged industrial economy (via History). In 1869, the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad linked small, isolated villages and towns to faraway cities. The journey from "sea to shining sea," once a six-month-long effort, now took only six days.

The internal combustion engine replaced the steam engine, and oil become a primary fuel source. Electricity came into widespread use. Steel production gave us bridges, skyscrapers, railroad tracks, and automated machinery. The telephone (1876), incandescent light bulb (1879), and gasoline-powered car (1885, via PBS), were born. Plastics were developed, agriculture was improved, and companies began to mass-produce consumer goods for a national market.

The Carnegie Steel Company made Andrew Carnegie a millionaire (via Forbes), and Standard Oil made John Rockefeller one, too (via Smithsonian). New York City turned its lights on, and railroad companies introduced standard time. Trusts and monopolies, using vertical integration, were able to control every aspect of an industry (raw materials, scarcity, profit, price, and the rest). Vertical integration and new organizational structure — much like the management structure in businesses today — allowed companies to operate at a much larger scale. The first corporations were formed. By 1890, more than half the nation's wealth was owned by just 1% of the population (via History).

The bribery

The wealthy could buy anything they wanted — even politicians. Bribery was commonplace during the Gilded Age, perhaps in part due to the "patronage system" (or "spoils system"). Introduced in the 1830s, the patronage system allowed government positions to be granted in exchange for political support, campaign work, and sometimes for campaign contributions. According to Encyclopedia, more than half of federal jobs in 1881 were "patronage" positions — corruption was rampant, and the system frequently gave way to a variety of abuses. The way government officials were paid also made them susceptible to bribery. Rather than being paid salaries, many officials could take home percentages of tax revenue, ”fees' owed, or even stamp sales as compensation (via History). "Taking a cut" might easily evolve into dirty deals.

Another source of notorious corruption was the rise of political machines ("machine governments"). When governments struggled to keep up with the overwhelming growth of cities, urban political machines (formerly regional associations) stepped in to take office. According to History, they could rig elections, buy votes, would regularly accept bribes, engaged in extortion, accepted kickbacks, and even rigged elections. Some accepted money from organized crime syndicates in exchange for immunity from the law. They operated outside of official government (and therefore the public eye), answering to their political bosses (via Britannica). Perhaps the most infamous political boss, Tammany Hall's "Boss" Tweed, was convicted on over 200 counts of fraud, and found to have stolen between $45 million and $200 million from government funds, according to History.

The Big Divide

While a wealthy family might live in a mansion with their bathtub and toilet quite literally covered in 23-karat gold gilding (via History), their workers likely lived in tenements with no sanitation at all. As income inequality skyrocketed, America's new millionaire class reveled in what Thorstein Veblen dubbed "conspicuous consumption," as The Guardian reported. The visually striking opulence on display would be the image of the Gilded Age to survive in American memory.

The vast majority of people in the Gilded Age lived their lives in abject poverty. Working conditions were dangerous, hours were long, and pay was low. By the year 1900, nearly 40% of Americans lived in cities, according to Oxford Research Encyclopedia. As cities scrambled to keep up with the influx of workers, many were crowded into alleyway shacks or tenement dwellings. According to The Journal of Economic History, most city dwellers spent their days performing repetitive tasks in large factories. If a worker was poor, their children might spend the day working alongside them. After 10 to 12 hours, they might come home to the tenement dwelling where they lived — most likely a dirty, overcrowded room without light or ventilation.

The Bill

Attempts to achieve better working conditions and fair pay were met with brutal repression. Railroad companies — one of which spent roughly $500,000 a year in bribes from 1875 to 1885, according to History — would also solicit the government's help to repress worker strikes. During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes sent in the National Guard at the railroad company's behest (via History). The result would be a bloody shootout. According to Explore PA History, soldiers shooting at a crowd left 20 people, including one woman and three children, dead. The New York Herald described the ground as "dotted with the dead and dying" (via Explore PA History).

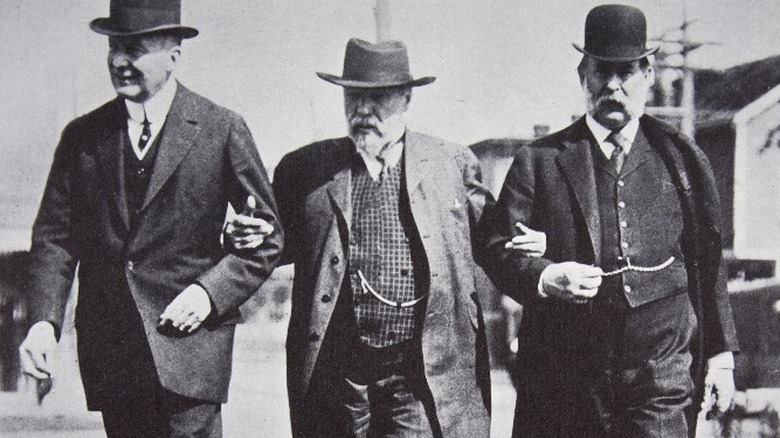

In addition to shooting their own employees, some railroad companies had no qualms about defrauding the federal government. Railroads were government-subsidized, so when Union Pacific Railroad Company completed the Eastern half of the Transcontinental Railroad, they simply had to send the government a bill. Union Pacific decided to set up a fake construction company — Crédit Mobilier — and bill the government for twice the actual cost of construction. To make sure they'd get away with it, Crédit Mobilier bribed a dozen congressional officials, according to History, offering to cut them in on the deal. Unfortunately for Crédit Mobilier and their friends in Congress, the scheme went south and they got caught. According to PBS, James Garfield (above) was among those accused of being entangled with Crédit Mobilier. He denied the charges and was later elected president.