World Leaders Who Took Power Via Coups

No leader of a nation lives forever; thus, aside from foreign invasions, the eventual transfer of power within countries, from one ruler to another, is inevitable. Unfortunately, that doesn't mean it will always occur peacefully. Over thousands of years, established methods of handing the reigns of power to the next ruling party, such as royal succession or popular elections, have been internally usurped by those who would prefer to simply muscle their way into the driving seat, otherwise known as a coup.

It so happens, from the 1960s onward, the number of military coups, whether they were successful or not, did begin to decline, according to the Pew Research Center. Reassuring, perhaps, that increasing global democratization can put the dampers on violent uprisings, as an article by CNBC discusses. This positive trend may not be one to take for granted, as history tends to repeat itself, and coups are most definitely not a new idea.

From the dawn of civilization, many influential, powerful, and established societies have seen their government toppled suddenly by those who decided they could do a better job at running things – or just fancied the seat of power and all its trappings for themselves. Here is a selection of world leaders from history who took power via coups.

Nabonidus of Babylonia

Over 2,500 years ago, the civilization of Babylonia, famed for the legendary hanging gardens of Babylon, was already ancient, having occupied a swath of territory in modern Southern Iraq for over 1,300 years, per Britannica.

Before the Persians swept in and ended the days of Babylonia as an independent kingdom, its last leader Nabonidus took power somewhat reluctantly, as The Reign of Nabonidus by Yale University Press describes — if a coup can be reluctant.

Nabonidus rose to prominence as a relatively minor member of the nobility who ended up becoming the pointy end of an uprising against the unpopular son of Nebuchadnezzar II, Labashi-Marduk, in 556 BCE. After making a number of reforms, he then upset the priesthood by tinkering a little too much with their state religion and ended up in exile, in Arabia, for much of his reign while his son Belshazzar ruled in his stead. He returned just in time to be defeated by Cyrus of Persia in 539 BCE, ending Babylonia's long and illustrious history as one of civilization's earliest empires.

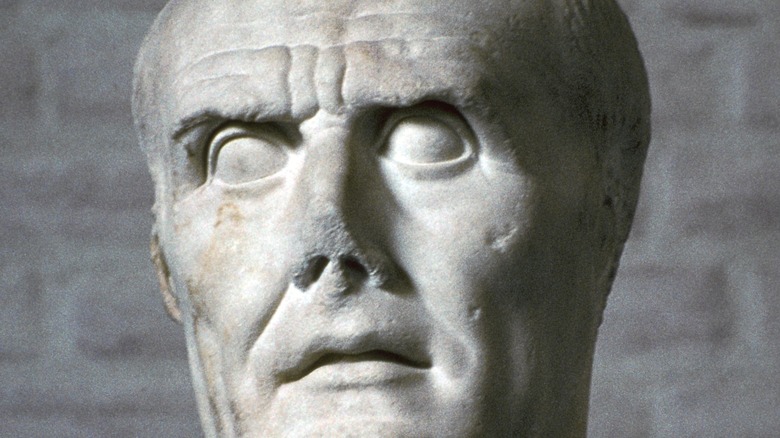

Sulla of Ancient Rome

From 83-82 BCE, ancient Rome was convulsed by its first civil war, from which the lowly ranked but ambitious noble Lucius Cornelius Sulla (usually known simply as Sulla) emerged as the victor, per Britannica. Earlier, while campaigning against King Mithradates of Pontus on Rome's eastern borders from 88 to 85 BCE, Sulla had been declared a public enemy by the rulers of Rome, his laws made in his previous position of consul were repealed, and his house was burnt down.

Sulla wasn't thrilled about this turn of events. Returning from Greece to the Roman mainland with a big bag of loot and an army of 40,000 men, Sulla marched on Rome in 83 BCE and set about massacring his way to victory over his opponents in Rome in 82 BCE. For the first time in its history, Rome appointed Sulla dictator for as long as he wished. This makes it all the more surprising that — after extensive political reforms — Sulla suddenly and voluntarily retired in 79 BCE, choosing a quiet life writing his memoirs until he died of natural causes in 78 BCE.

While Sulla may not have left the most significant mark in the annals of history, he certainly left an impression on a young Julius Caesar, who was captured and then pardoned by Sulla, as described by an article in Historia.

Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire

In 610 CE, as the Eastern Roman Empire was crumbling under the weight of war, famine, and disease, as detailed by Britannica, Heraclius stepped ashore at Constantinople with murderous intent. The object of his ire was Phocas, then emperor of Constantinople, whose incompetent leadership had prompted the nobility to call for "regime change."

According to "Heraclius, Emperor of Byzantium," in an exchange worthy of an '80s action movie, Heraclius confronted Phokas and exclaimed, "Is it thus, O wretch, that you have governed the state?" His grim retort, "No doubt you will govern it better" earned Phokas a swift and terrible comeback from Heraclius, who set about butchering Phokas to pieces.

After his bloodthirsty revenge, Heraclius rallied the people of Constantinople and its surrounding domains, rebuilt the kingdom's defenses, and, through deep reforms of the military and economy, restored Byzantium's strength enough that it was able to withstand four centuries of foreign invasion. Heraclius himself fell to a painful diseased death in 641 CE.

Edward III of England (or really his mother, Isabella of France)

Edward of Windsor's ascent to the throne of England as Edward III was quite the family affair. As detailed in Britannica, in 1327 Edward III replaced his father Edward II by the hand of his mother, Isabella of France (Edward II's wife), at the tender age of 14. Unhappy with the way her husband Edward II was treating the nobles of his country, as well as the confiscation of her English properties by his supporters, Isabella, together with her lover Roger Mortimer and the support of the English nobility, raised an army against Edward II and forced his abdication.

With her young son Edward III, not yet old enough to rule by himself, now on the throne, Isabella and Roger Mortimer governed England in Edward III's name until, in 1330, Edward III got married and decided it was time to do some ruling himself. Clearly most dissatisfied with Mortimer, at night Edward II snuck into a castle in the English city of Nottingham and had Roger Mortimer seized and executed, per the BBC. Edward was more forgiving to his mother Isabella but politically sidelined her, ruling England with considerable vigor until 1377.

Selim I of the Ottoman Empire

In a civil war over the Ottoman Empire, centered in modern-day Turkey, in 1512 Selim I defeated both his brother, forced the abdication of their father Sultan Bayezid II, then eliminated all but one heir to the kingdom – his son Suleyman, per Britannica.

Dubbed "Selim the Grim" by some due to his sour appearance, mentioned in an article by Egypt Today, during his consolidation of power he not only took the place of his living father and predecessor Bayezid II but also killed all his brothers, then slaughtered all seven of their sons as well as all but one of his own sons, the aforementioned Suleyman, according to Britannica.

During his 8-year reign as the Ottoman sultan, Selim greatly expanded the borders of the Ottoman Empire to include Syria, Egypt, and Palestine, crushed opposition in Iran and Anatolia, and eventually won the keys to the holy city of Mecca and was acknowledged as the leader of the Islamic world.

Catherine the Great of the Russian Empire

Originally named Sophie Friederike Auguste, from a relatively obscure branch of the tangled thicket of European aristocracy, Catherine the Great's unlikely assistant in her path to power was her husband Peter III, as the BBC details. A stark contrast to the intelligent and ambitious Catherine, her husband and emperor of Russia, Peter III, was a neurotic alcoholic and obsessed with Russia's rival Germany, according to Britannica. In addition, after her husband's predecessor, the empress Elizabeth, passed away, once he became emperor he promptly put an end to the ongoing war between Russia and Prussia, making an alliance with Prussia's Frederick II. His lack of Russian patriotism and distaste for his wife prompted Catherine to take advantage of the broad goodwill the people and ruling class held towards her.

Less than a year after Peter had become emperor, with the support of both the army and prominent members of the aristocracy, Catherine and the regiments she led rode into St. Petersburg, where she was proclaimed supreme empress in Kazan Cathedral. Peter III was forced to abdicate and ended up dead eight days later, likely assassinated. Later crowned with far more ceremony in Moscow, she ruled over an expanding empire for over three decades until her death by a stroke in 1796.

Napoleon Bonaparte of France

From his birthplace of the Mediterranean island of Corsica, itself occupied by France during his childhood, according to History, Napoleon Bonaparte began building the groundwork for his eventual dominance of France after graduating from the military academy of Paris in 1785 – ranked a modest 42nd out of 58. Until 1799, Napoleon took part in and led numerous military campaigns that grew his reputation as a brilliant, ambitious, and ruthless leader, culminating in the coup of 18-19 Brumaire 1799.

Following the French revolution of 1789, the government settled into two legislative councils and an executive branch of five members called the Directory, per Britannica. Lured by co-conspirators of Napoleon by a threat of a plot against the councils, the government met at a palace conveniently away from the city and amongst troops loyal to Napoleon, as described in Britannica. After a fumbled speech that caused so much uproar that he had to flee the room, Napoleon's troops moved in and forced the councils to dissolve and abolish the Directory, replacing them with a consular government – headed by the First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte.

As his military and political power grew, Napoleon shed any pretense of egalitarianism and became Emperor of France in 1804, holding power until his defeat at Waterloo and imposed exile to the island of St. Helena in 1815.

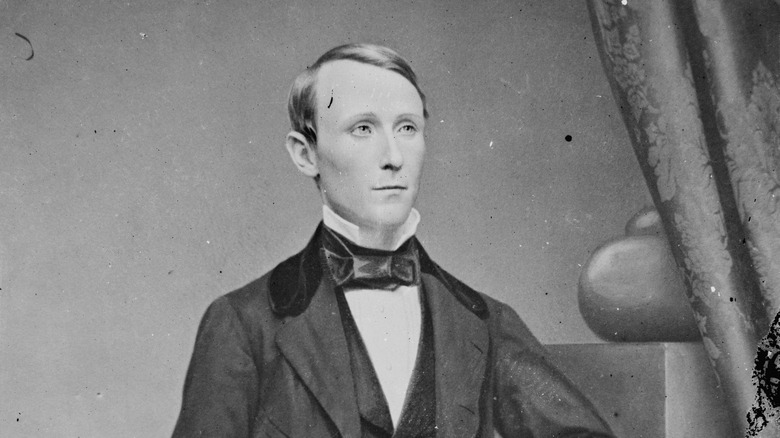

William Walker of Nicaragua

William Walker was an adventurer from Nashville, Tennessee, who in 1856 managed to bully his way to an (almost) year-long term as president of the Central American country of Nicaragua, according to Britannica. Walker was one of many private U.S. citizens that sought to conquer lands in Central and South America during the 19th century, a practice known as "filibustering," as described by History. The idea of the United States having a "Manifest Destiny" was a central justification for the young William Walker's ambitions, so after failed attempts at playing the colonialist in Mexico, Walker turned to Nicaragua.

There, during a civil war, Walker picked one of the warring factions as an ally and marched his American-Nicaraguan army of almost 300 into the city of Granada, whereupon he proclaimed himself president. Recognized as such by the U.S. in 1856, Walker's presidency of the Central American country soon turned sour after upsetting the U.S. tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, who put his considerable resources into raising an army against Walker, forcing him from power after just ten months.

Vladimir Lenin of the Soviet Union

It was in 1888, during a period of exile for illegal political activity in Kazan, Russia, that Vladimir Ilich Lenin read Karl Marx's "Das Kapital," amongst other revolutionary political literature, according to Britannica. Over the succeeding decades, Lenin would immerse himself in the pursuit of establishing a socialist government in Russia, which fell within reach after the Tsar was deposed and replaced by a provisional government in 1917. However, Lenin believed this was merely the first step towards the end goal of a nation truly governed by its workers, and set about convincing his Bolshevik party that another revolution was needed.

Months later, with the people of Russia growing disillusioned with war-weariness and a collapsed economy, in October 1917, Lenin and his Bolsheviks arranged for their troops, the Red Guard, to take up strategic positions in Petrograd (modern St. Petersburg) before declaring the overthrowing of the Provisional Government, as detailed by Britannica. The chairman of the Provisional Government, Kerensky, found himself without military support of his own and was helpless to intervene.

After some resistance from military cadets and students, which was swiftly crushed, a new Bolshevik-dominated government was formed, ostensibly in the name of the people but operationally under the direct control of Lenin himself, now the leader of the largest country in the world. Lenin remained head of state of the Soviet Union until his death from illness in 1924.

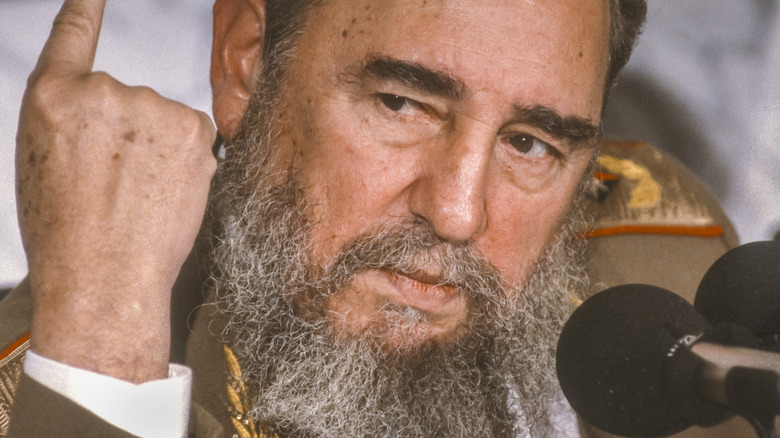

Fidel Castro of Cuba

From 1952, Cuba was governed by the unelected dictatorship of General Fulgencio Batista, according to Britannica, who had himself had in 1952 overthrown president Carlos Prio Socarras and put an end to the upcoming elections. Already practiced in political activism and with a failed attempt to overthrow the government of the Dominican Republic, as well as one previous near-fatal attack on Cuba's government, under his belt, Castro led his second attempt to topple the Batista regime in 1956. His expeditionary force of 81 men was beaten back into the Cuban mountains along with his brother Raul, the charismatic T-shirt poster boy Che Guevara and nine others.

Waging an extremely effective guerilla warfare and propaganda campaign, Castro's force of 800 defeated Batista's vastly larger 30,000 strong army, forcing the latter to flee the country and allowing Fidel Castro to take command in 1959. Aligning his government and socio-economic policies with the socialist Soviet Union, Castro remained firmly in power until, with his health ailing, he stepped down in 2008, per the Guardian.

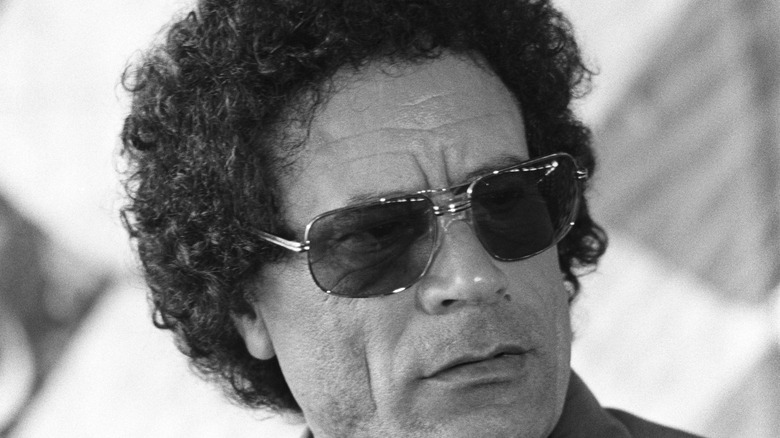

Muammar Gaddafi of Libya

Born in a tent to nomadic Bedouin farmers, according to Britannica, Muammar Qaddafi's ambition to seize control of Libya began early in his military career. After progressing through the ranks, Qaddafi achieved his goal in September 1969, when he and a group of young army officers deposed King Idris in a military coup, waiting until Idris was out of the country for medical treatment in Turkey, per History, and became both commander in chief and chairman of the ruling Revolutionary Command Council.

Over the following months Qaddafi took control of Libya's oil industry, then the third-largest oil exporter in the world, jailed 600 key individuals from the military, government, and industry, as contemporaneously reported by Time, outlawed beer and whisky as part of a reinstating of Islamic laws, and removed all foreign-language signage. Until his own violent overthrow in 2011, for over four decades Qaddafi ruled Libya as an Islamic socialist state, often isolated from the global community, while he traveled with a vast, eclectic wardrobe and a tent so heavy it needed to be flown on its own plane, according to ABC News.

Idi Amin of Uganda

A former assistant cook in the British colonial army, the King's African Rifles, according to Britannica, Idi Amin's humble beginnings would belie his future as one of the most capricious dictators in modern history. Managing to work his way to officer rank in the Ugandan army prior to independence in 1962, then becoming the army and air force chief from 1966 to 1970, he staged a military coup in 1971 against the prime minister and president Milton Obote. With himself now president, Idi Amin would further promote himself to field marshal and life president within five years.

According to the Wilson Center, the death toll for politically motivated killings under Adi Amin's rule may have reached as high as 300,000, many of which were committed by Amin's State Research Bureau, who had a free license to kill with the flimsiest of excuses. His brutal reign lasted until 1979, when an overambitious attack on Tanzania backfired and Amin was forced to flee the country, eventually ending up in Saudi Arabia.

Pol Pot of Cambodia

In 1975, according to Britannica, the communist Khmer Rouge guerrillas overthrew General Lon Nol's military government of Cambodia, beginning a reign of terror that would kill over one million people. Led by Pol Pot, a revolutionary name adopted by the former Saloth Sar, who first enamored himself with communism during his studies in Paris, the Khmer Rouge had allied with Prince Norodom Sihanouk, who had previously been forced out by the U.S.-back Lon Nol, as reported by Reuters.

Sihanouk encouraged the people of Cambodia to join the fight with Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge, building their numbers until they were able to topple Lon Nol's own regime. The Cambodian people were rewarded with the brutal imposition of forced labor, forcible displacements, and the subsequent deaths of millions. Pol Pot was driven out of Cambodia during an invasion by Vietnamese forces in 1979, where he continued to guide the Khmer Rouge until he too was excised from its leadership in 1997.

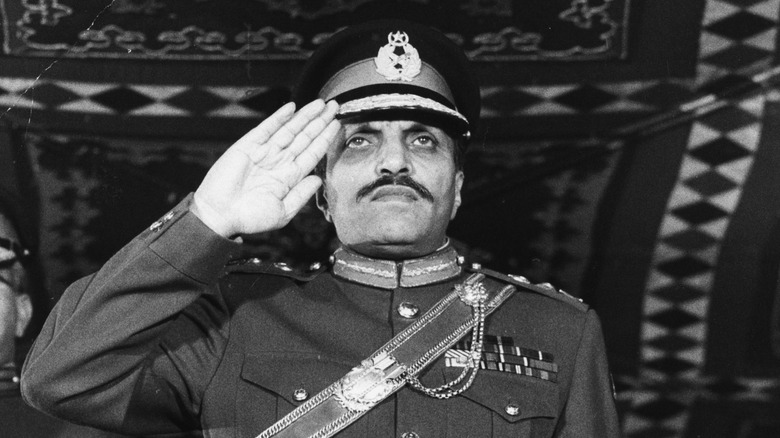

Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq of Pakistan

From 1945 until 1976, the Indian-born Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq had a successful military career behind him, even presiding over military courts trying alleged plotters against Pakistan's Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto from 1972, according to Britannica. Bhutto rewarded him with promotions to lieutenant general and then chief of Army staff by 1976. But in a bloodless coup in 1977, Zia took power from Bhutto and in 1979 executed him for attempted murder.

As the Washington Post reported at the time, Zia-ul-Haq may have been a reluctant leader of the coup, persuaded to take part by six of his army commanders and subsequently released a statement saying, "We wish to make it absolutely clear that the Pakistan army, navy, and air force are totally united to discharge their constitutional obligations in support of the present legally constituted government."

Nonetheless, further measures to tighten his hold on power took place over the following years, including the declaration of martial law until 1985, bans on political parties and labor strikes, as well as strict press censorship, until his death in an airplane crash in 1988.