The Real Reason Students Put A Car On Trial In 1970

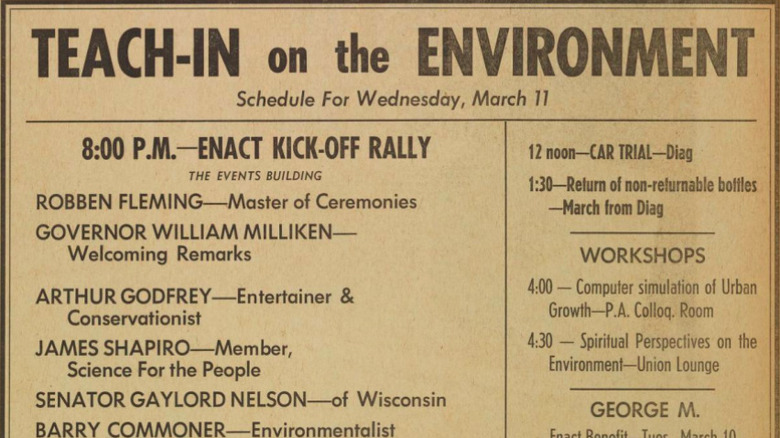

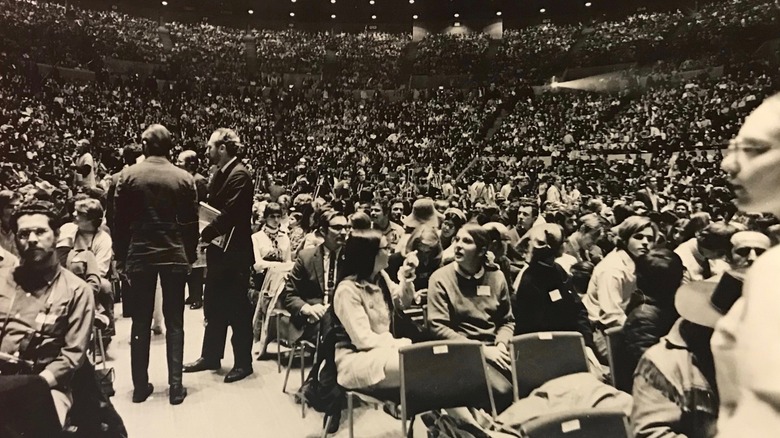

Just one month before the world's first Earth Day was celebrated, an epic teach-in drew hundreds of people to the quad at the University of Michigan for a major gathering of people in support of environmental justice, according to the University of Michigan. Students, teachers, and members of the general public came to hear speeches from one of the founders of the modern environmental movement Barry Commoner, environmental activist Ralph Nader, and the founder of Earth Day, Gaylord Nelson (via Smithsonian Magazine).

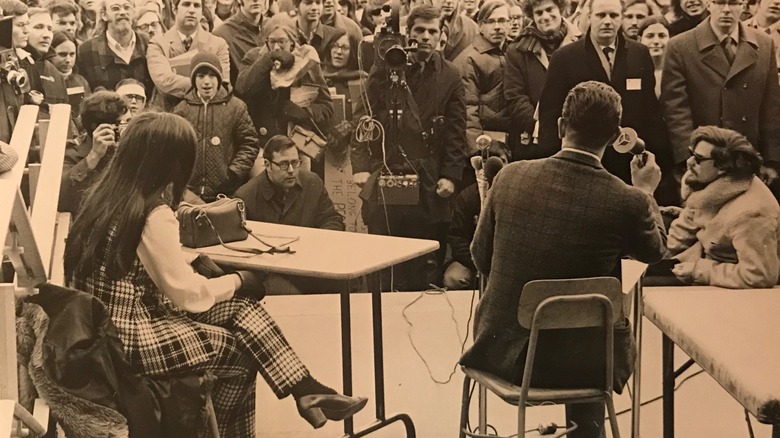

But, one activity included in the agenda was strikingly bold, somewhat violent, and more than a little funny. A mock trial was set up for one of the main culprits of environmental disregard at the time: the car, namely a blue and white 1959 Ford sedan. In the car's defense stood "Rob Rockyfeller," as did "Dr. Sigmund Ford," who claimed the automobile was "essential to the maintenance of the American's psyche," (per Smithsonian Magazine).

The charges

At the time of the mock trial, 40% of the country's auto industry workers resided in Michigan, according to EcoCenter. Mostly due to automobile production and use, air pollutants, in general, were 73% higher than they are today, according to Smithsonian Magazine. As such, cars were common subjects for similar environmental teach-ins across the country. At San José State University that winter, students bought and buried a brand new car to make a point about their wastefulness. At Florida Technological University, students similarly charged a Chevrolet with air pollution (via TIME).

However, the blue and white Ford sedan on trial in Michigan faced a number of other charges in addition to accusations of pollution. Murdering Americans in traffic accidents and creating the ungodly phenomenon of traffic were listed as well as making Americans dependent on cars, and "discriminating against the poor," which referred to redlining and disproportionate pollution in communities of color (per Smithsonian Magazine).

The verdict

During the trial, the judge acted distracted and aloof. In hand he held an issue of "Auto Racing," an old 1970s car magazine, and was only briefly disturbed from his reading to make the verdict. In the end, he sided with Dr. Ford and ruled the sedan innocent, according to Smithsonian Magazine. Then, he had the gall to accuse the activists of siding with the prosecutor and "conspiring" against the sedan.

In an act of rebellion, the student activists "debenched the judge," and gave the deciding power to the people in the audience, who voted the "four-wheeled monstrosity" guilty and sentenced it to death, per Smithsonian Magazine and the University of Michigan. To unleash their anger against the automobile, students beat it to death with sledgehammers and baseball bats.

The sentence seemed to be well received. According to the University of Michigan, one 12-year-old boy in attendance said he thought the car smashing was a good thing because "cars pollute a lot of the atmosphere and I think we ought to get rid of it." Another woman said demonstrations like the beating-to-death of the car should happen more often.

The impact

Some of the audience members were already making headway in the environmental movement, like Barry Commoner, Ralph Nader, and Gaylord Nelson. But, the quirky theatrical production perhaps helped shape the lives of other people in the audience to become more involved in the environmental movement. A young Doug Scott would eventually lobby Congress for the Wilderness Society and the Sierra Club, leading to the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980, as Smithsonian Magazine points out.

This demonstrative display of a burgeoning anti-gas guzzling sentiment seemed to help the environmental movement gain traction. Within a year, the country would celebrate its first Earth Day and establish the Environmental Protection Agency, according to TIME.

However, some of the attendees recognize the inherently wasteful nature of the performance itself. Much like buying a brand new car to bury it and make a point, destroying a car was a bit childish and "quite elitist," George Coling, a graduate student at Michigan's School of Public Health at the time told Smithsonian Magazine. Coling, who became an activist focused on highway development, said the demonstration failed to take into account "the very real need that people have for transportation." Apparently, the student who donated the car to the production had just bought a new car himself, proving Dr. Sigmund Ford's dependence point.