Chilling Details From The Attica Prison Riot

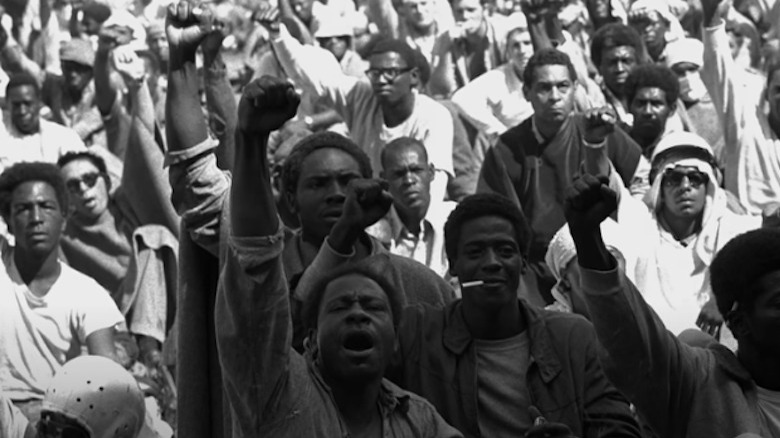

The year 1971 saw a wave of prison riots across America. After Black activist George Jackson was killed at San Quentin prison in California in August, the prison revolted, according to the UCLA Rebel Archives. His death elicited a mournful tribute from prisoners at Attica Correctional Facility in Wyoming County, New York. According to The Nation, prisoners at Attica arrived at the mess hall for breakfast, all wearing some form of black, and went on a hunger strike.

A month later, Attica experienced its own mutiny in what became the deadliest prison riot in American history, according to NBC News. It's uncertain whether Attica's uprising was inspired by San Quentin and Jackson's activism. It's clear, however, that prisoners at Attica had long advocated for a change to their dire living conditions and had long been denied. In July of that year, five inmates organized for prison reform under the name "Attica Liberation Faction." They sent a list of 28 demands to Russell Oswald, the New York commissioner of corrections, who responded with a perfunctory promise to consider them, but the inmates never received a worthwhile response, according to USA Today. This was a pivotal mistake, as anger and resentment at Attica was reaching its tipping point.

On September 9, the men at Attica seized control of the prison, and a few days later, state troopers and prison guards engaged in a bloody battle to take it back. The entire event resulted in 43 deaths. Here are some chilling details from the Attica prison riot.

Prisoners Were Subjected to Inhumane Treatment

Inmates were allowed only one shower a week and one roll of toilet paper a month, according to The Nation. There were issues of overcrowding, and the prison was reportedly 600 people over capacity. The medical care they received was so dire that prison civilian staff took notice. According to historian Heather Ann Thompson, author of "Blood in the Water" (via The New Yorker), when a medical worker at Attica was viewed as responsible for an inmate's death, the staff considered taking action by protesting outside their clinics. "We had sick men who had never received any medical attention in Attica," said riot leader Richard Clark said (as quoted in Time). While an outside doctor was allowed in during the riot to help injured hostages, he ended up treating prisoners for untreated health problems neglected while they were incarcerated.

To make matters worse, prison guards were not sufficiently trained and came from local, rural communities where other jobs were sparse, according to documentary filmmaker Stanley Nelson, in an interview with NPR.

According to former inmate Arthur Harrison (via NPR), prison guards would form "goon squads" at night and storm into cells, four or five at a time. Without the ability to defend himself, an inmate would get beaten and sometimes forcibly taken into solitary confinement for a beating. Former inmate Albert Victory said these regular beatings are what caused the prisoners to detonate. "That's the way it was done. Men just couldn't take it anymore," he said (as quoted in The Nation).

"We had sick men who had never received any medical attention in Attica," riot leader Richard Clark said (as quoted in Time)

Black Prisoners Were Treated the Worst

Arthur Harrison, an inmate serving time during the riot, said that Black prisoners were treated like they weren't human, as quoted in NPR. "It reminded me of the things I used to hear about on plantations in slavery," he said.

Attica's employees and staff were entirely white. Meanwhile, 54% of the inmates were Black, 37% were white, and 9% were Hispanic, according to USA Today. Recorded conversations of President Richard Nixon discovered decades later revealed a very telling narrative. When the riot was over and media coverage was still forming public perception, Nixon discussed the racial disparity with his chief of staff, saying, "That's going to turn people off awful damn fast that the guards were white" (via The New York Times). He and the governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, both agreed that the American public would sympathize with the state's brutal retaking of Attica because the riot would be seen as "basically a black thing," according to Nixon.

The Siege Lasted for Five Days

The uprising launched a day before the siege, on September 8, 1971. Two inmates were caught fighting in the prison's A yard, according to The Marshall Project. One was sent to solitary confinement, dragged from his cell by a "goon squad." Rumors spread throughout Attica that he had been beaten and was possibly dead, according to USA Today. The situation caused unrest among inmates, and the next morning, Attica was placed under lockdown with gates leading to other cell blocks locked.

As USA Today details, corrections officers locked a number of prisoners into a tunnel that led from their cell block into the prison's central command center called "Times Square." The prisoners began to riot out of fear of beatings from the goon squad, according to The New Yorker. Remembering the inmate who was supposedly killed the night before, they feared for their own lives. When they discovered that the gate locking them from Times Square could be compromised, they broke through the gate and attacked the guards on the other side. The prisoners stole their keys and established control of Attica.

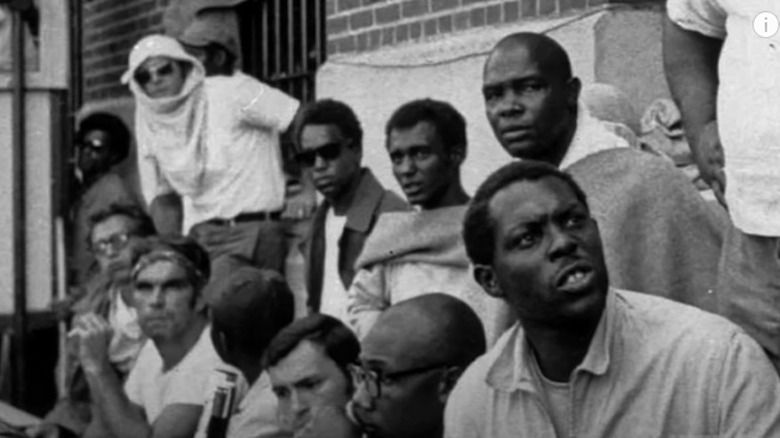

With nearly 1,300 inmates freed and over 40 employees held captive, the rioters organized a new way of life. Inmates set up tents in the prison yard, and Vietnam veterans built latrines. Prisoners with nursing experience set up medical stations, according to NBC News. Most of their energy was spent negotiating with authorities, however, which failed by the fifth day of the siege.

Rioters Murdered a Corrections Officer

When the prisoners first took hold of Times Square on day one of the siege, they beat several correctional officers, including 28-year-old William Quinn. Other inmates carried Quinn on a mattress to authorities so that he could receive immediate treatment, notes The Daily Messenger, but he soon died of skull fractures at a nearby hospital, according to The Marshall Project. Murder charges were filed against two inmates, including one who used a 2-by-4 board to injure Quinn. One former inmate said that Quinn used to protect him from physical attacks by other inmates and described him as a "guardian angel," and that several other inmates tried to rescue Quinn, according to The Daily Messenger.

When news of Quinn's death found its way back to the prison, the inmates feared legal retaliation. They demanded complete amnesty during their negotiations, but they knew that they were losing leverage. According to Time, the prisoners knew their other hostages — consisting of prison staff — protected them from a sudden onslaught by state police. Quinn's death was a sudden obstacle. "It was a turning point when Quinn dies," filmmaker Stanley Nelson said in an interview with Salon. "All bets are off because someone has been murdered. It is harder to give them amnesty because of the optics; it sets a precedent."

Muslim Prisoners Provided Security

As prisoners took over control of Attica, Muslim inmates immediately set up a security perimeter in the prison's D yard in order to protect the prison staff kept hostage, according to USA Today. Hostages, scared for their lives, felt these Muslim prisoners were their only line of defense. According to Time, whenever outside observers and mediators left, the hostages grew more anxious and were afraid about whether or not the Muslim inmates could truly offer protection.

Ironically, Muslim prisoners had already struggled to survive at Attica on their own terms. Attica didn't recognize Islam as a "legitimate religion," according to The New York Times. They were also fed pork, which is violation of halal dietary restrictions (via Courthouse News). In the years since the riot, Attica struggled to adhere to the 28 promises and reforms made to prisoners during the negotiations. Fortunately, Attica succeeded in establishing religious liberties for Muslims. Today, Muslim prisoners are allowed to own kufis and prayer rugs, and diet restrictions during Ramadan are accommodated, according to The New York Times.

Prisoners Demanded Release to a Foreign Country

On the first day of the uprising, after taking control of Attica, the prisoners released a series of six demands from officials, including a "speedy and safe transportation out of confinement to a nonimperialist country" for anyone who wants it, according to The New York Times.

Other demands included complete amnesty and protection from physical and legal reprisals, an end to censorship of their reading materials, increased communication with the outside world, and federal oversight with the prison. According to The Marshall Project, they also demanded an outside group of journalists, lawyers, and activists to observe prison conditions and act as mediators.

After further negotiations with State Correction Commissioner Russell G. Oswald, the prisoners created a more thorough list of "15 Practical Proposals," including an end to slave labor. The negotiations between the prisoners and Oswald ended with a list of 28 proposals that officials agreed to, but never included complete amnesty. According to Stanley Nelson (via Salon), the continued rebellion hinged on complete amnesty from crimes committed during the uprising, but it was never granted to them.

The Governor of New York Refused to Negotiate

Prisoners demanded that Gov. Nelson Rockefeller visit Attica Prison's D yard in-person for negotiations, but he refused. Since the inmates were demanding total amnesty, which he was not willing to give, he believed his presence during negotiations would be of no consequence, according to The New York Times. He drove a hard bargain to quell the rebellion and inferred that the use of force was imminent if inmates didn't soon surrender or accept Russell G. Oswald's 28 concessions. The observers advocated for his presence, believing it essential to negotiation.

His own commissioner recommended his visit, and a state commission formed in the riot's aftermath criticized his decision to refrain, although they admit that his presence would not have prevented violence, according to The New York Times.

Rockefeller proceeded to approve the operation to retake Attica despite knowing the lives of many hostages were at risk. Within hours of the revolt's dismantling, Rockefeller phoned President Richard Nixon to brag about the successful assault, calling it "a beautiful operation," according to The New York Times. Nixon approved his reticence against providing amnesty, saying it prevented uprisings in prisons across America.

Tear Gas is Dropped Onto Prisoners

On September 13, 1971, the New York state police prepared to retake Attica. Russell G. Oswald provided prisoners with an ultimatum, offering them one final chance to release hostages, but they refused, according to The Marshall Project. As state authorities began their raid, inmates were suddenly overwhelmed by a green gas that obscured their vision, according to NBC News. Helicopters above the prison's D yard had begun flooding the prisoners with tear gas.

The smoke hindered the ability for the troopers to see, so they began shooting indiscriminately for nearly nine minutes into the prison yard, according to filmmaker Stanley Nelson (via NPR). A helicopter from above urged inmates to surrender with their hands up, but there was no visibility for an effective surrender, and officers kept on shooting. They fired 3,000 rounds, according to History.

Even after police reports declared their mission a success, observers at the site continued to hear gunfire. Ten hostages and 29 prisoners died from the onslaught, according to The Marshall Project.

Most Casualties were Caused by Law Enforcement

Out of the riot's 40-plus casualties, 39 were caused by state police, according to History. This included 29 inmates and 10 hostages. The raid to retake Attica was comprised of 500 law enforcement officers, including state troopers, corrections officers, and prison guards, according to NPR. The onslaught came as a shock to rioters, who although fearing the worst in the preceding days, thought keeping prison staff as hostages would protect them all from this type of bloody assault.

A larger narrative emerged in the aftermath to justify the brutal raid. As The Marshall Project details, Gerald Houlihan, the New York Department of Correctional Services public relations director, told reporters that prisoners had slit the throats of seven or eight hostages. Deputy Commissioner of Correctional Services Walter Dunbar claimed that prisoners castrated another hostage. Both claims were false. Gov. Nelson Rockefeller admitted that the false claims attributing hostage abuse to prisoners was embarrassing and unfortunate (via The Marshall Project.) When it became clear that police force was responsible for the deaths of 10 hostages, Rockefeller confessed to the setbacks of the operation: "You can't have sharpshooters picking off the prisoners when the hostages are there with them, at a distance with tear gas, without maybe having a few accidents," reports The New York Times.

Prisoners were Forced to Run the Gauntlet

The takeover didn't end with 39 dead. After law enforcement succeeded in regaining control of Attica, officers began punishing inmates with cruelty. They forced prisoners to strip down until they were naked and barefoot and forced them to crawl through the latrine the prisoners had made days before. Officers threatened to kill the prisoners if they lifted their heads from the waste, according to Stanley Nelson (via NPR). Some prisoners were shot several times and then forced to crawl, according to History.

According to James Asbury, a 20-year-old Attica inmate at the time, 30 to 40 officers lined up in a broken glass-strewn hallway and armed themselves with billy clubs, pickaxes, and pipes. They then forced the barefoot prisoners to march through them in a makeshift run-the-gauntlet. If any of the prisoners fell, they would be beaten, Asbury said to NBC News in an interview.

According to Heather Ann Thompson (via New York Post), once officers regained control of Attica, they were "determined to make Attica's prisoners pay a high price for their rebellion." Some prisoners heard racial slurs and "white power" chants. Attica's doctors taunted prisoners who were abused as officers rubbed salt and quicklime onto prisoners' wounds.

Only One Officer was Charged

According to The Marshall Project, over 60 inmates and one guard were charged in the aftermath. Eight of those inmates were convicted, and the charge against the guard was dropped. In 1976, stating that he wanted to "close the books on Attica," Gov. Hugh Carey granted clemency to seven of those inmates and commuted the sentence of the eighth, according to Britannica. The inmate convicted of murdering Officer William Quinn was among them, according to The Daily Messenger.

As the New York Times details, in 1974, inmates filed a $2.8 billion class-action lawsuit. It wasn't until 2000, however, when the suit was finally settled, with $8 million being awarded among them. In 2005, surviving hostages and families of officers killed were given $12 million, according to NBC News. James Asbury said he was nearly beaten to death, but his injuries were not judged as critical, so he was only given $6,000.

Abuse At Attica Continues

Nearly 40 years after the deadly uprising, in 2011, inmate George Williams, who had only four-month's left on his sentence at Attica, was beaten by officers, leaving him unable to walk, according to The Marshall Project. Some witnesses report that as many as 12 officers joined the assault. Williams had to be taken to an outside hospital, and his injuries included a broken shoulder, cracked ribs, and two broken legs. The doctors said his injuries were a result of "blunt force trauma."

The incident began when the officers ordered Williams to a strip-search, alleging his possession of a razor-blade and an "ice pick-like shaft," according to The Marshall Project. According to Heather Ann Thompson's "Blood in the Water," correctional officer Mike Smith considered Attica's strip searches so shocking, that "he would have considered suicide had he been forced to undergo one," as quoted in The New Yorker. However, Smith was employed in the 1970s, at the time of Attica's deadliest riot.

One would be forgiven for assuming not much has changed, and they would be mostly right. According to The Marshall Project, there were 228 alleged assaults committed by staff from January 2010 to November 2013. But in 2015, Attica decided to enter the 21st century by installing surveillance cameras throughout the prison. The measure — along with improved training of officers — saw an 80% drop in assault filings. Half a century later, the tides might have finally begun to turn at Attica.