Here's Who Inherited Benjamin Franklin's Money After He Died

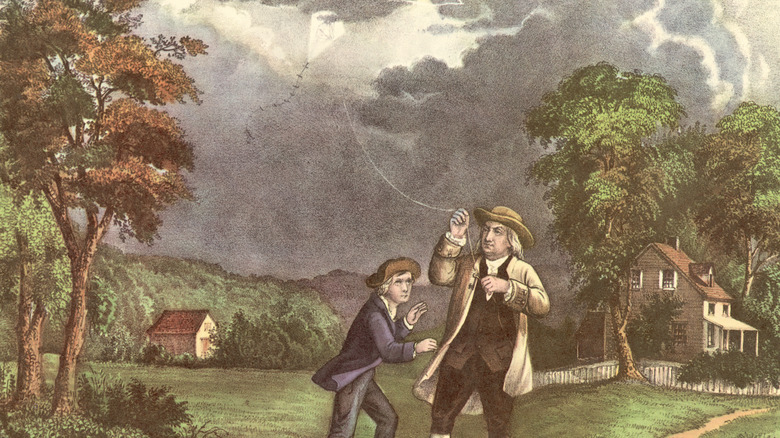

Benjamin Franklin is known to Americans as a Founding Father, a contributing writer of the Declaration of Independence, a science whiz, author, and social-services inventor (via Britannica). By 1740, he was among the wealthiest men in America. And he had lots of ideas about money that were way ahead of his time, including what he would do with his own cash after he died.

Franklin was born in Boston, and spent much of his life traveling between Philadelphia and France. Per Britannica, Benjamin Franklin suffered from both gout and kidney stones in the later years of his life. By 1785, Franklin had a hunch that he was going to die soon, and although he loved living in France, he wanted his legacy — and money — to remain in America.

He was interested in the idea of his money creating compound interest after he died (via Celebrity Net Worth). He was inspired by Charles-Joseph Mathon de la Cour, who encouraged Franklin to leave small amounts of money towards different charity projects. Then, over time, the money would collect interest exponentially, and could stretch much further than Franklin's original investment. Franklin agreed to bequeath £2,000 pounds, which would be about $4,400 U.S. dollars today. Benjamin Franklin died on April 17, 1790, at age 84.

Big plans for his money

To start off, Franklin left some things to his family, according to Living Trust Network. He gave his son William his books, papers, and some land he had in Nova Scotia. To his daughter, Sarah, he bequeathed numerous U.S. houses and properties. He gave other properties to his sister and grandson. But Franklin had bigger plans for his will, too.

He had some very precise details laid out for how the money should be spent. Franklin dedicated $2,000, reports The New York Times. This money, he stipulated, should be evenly split between Philadelphia and Boston, the two American cities he called home. And it should go to "young apprentices," as he had been in his youth. After a century, some of the money would be distributed, and then after another century, the rest could be dispersed.

Celebrity Net Worth reports that Franklin thought his funds might grow to $130,000 after a century or two. He wanted $100,000 to go to public works, funds that would be distributed in 1890. The other $30,000 would remain untouched until 1990, growing to an even larger amount, and was then to be given to state governments as well as local citizens. Franklin wanted this money to be loaned to "young married artificers," to be paid back over a decade.

One century later

For the first 100 years, the money grew through loans that went to a specific group of apprentices (per Mental Floss). To receive a loan, they needed to be men under 25 years old, married, and working in a mechanic apprentice role. But by the 1880s, apprenticeships were falling out of fashion, and critics said the funding was growing irrelevant after so many years.

In 1890, people were excited to use the primary portion of the money, which had appreciated throughout the years, as Mental Floss reports. Philadelphia had about $70,800 to spend, and Franklin's will stipulated that 75% should go to public works projects. Philadelphia gave their amount to the Franklin Institute. The museum engages people of all ages with hands-on exhibits, classes, and resources about science and technology (via The Franklin Institute).

Boston, which had made smart investments with their share, had about $327,800 to spend (via Mental Floss). People suggested the money could pay off state debts, build a community bathhouse, or open a public recreation center.

Millions of dollars to spend

Unfortunately, officials spent 14 years arguing over how it should be used. And finally, in 1904, the Boston funds were confiscated by a state court (per The New York Times). They admonished elected officials, who had misappropriated it for their own trips.

The money was eventually used to open a trade school, per Mental Floss. Andrew Carnegie, a philanthropist with money to burn, made an agreement with Boston officials, saying he would donate money if Boston donated land and also used some of the funds to build a two-year trade and technical school. Four years later, The Franklin Union was opened to the public, and was later renamed the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology.

Benjamin Franklin's control over his money began to slip in the 1950s, reports The New York Times. The Massachusetts state legislature and the governor passed a law in 1958 that would have ended Franklin's trust fund. This law was designed to give the entirety of the money to the Franklin Institute. But instead, the Supreme Court stepped in, and arguments continued in the courtroom.

Controversy erupts

The strict nature of the Franklin trust funds also weakened over time, allowing for other uses, reports Mental Floss. Starting in 1960, more than 7,000 medical students received educational loans over a 30-year period. That meant in 1990, the public was ready to receive the second round of money, which had ballooned to $6.5 million (per The New York Times). Boston would receive $4.5 million, and Philadelphia would receive $2 million. The Massachusetts fund was reportedly larger simply due to a "wiser handling of the investment" over many years.

But there was lots of controversy over what it should be used for (per The New York Times). As the attorney general of Massachusetts pointed out, there was currently a billion-dollar budget deficit, so what could a mere $6.5 million possibly accomplish? And what actually ended up happening to the 1990 Pennsylvania and Massachusetts funds?

First, per Celebrity Net Worth, Philadelphia had $2 million to use. They originally wanted to dedicate $520,000 to promote tourism to the city. But a loud public outcry curbed this idea.

Long-term legacies

Other Philadelphia residents pushed for the money to go to low-income housing or to support education (via Mental Floss). Ultimately, it was decided that the money would be used for education, giving aid to young folks who were studying trades and applied sciences (via Celebrity Net Worth). As for the remaining $1.5 million, these funds ended up in the state of Pennsylvania's reserved financial resources.

Concerning Boston's $4.5 million, after several years of arguments in court, the Franklin Institute (pictured above) won big (via Mental Floss). The educational institute in Boston claimed in 1990 that they should be the sole beneficiaries of the $4.5 million Massachusetts fund (per The New York Times). They cited the 1958 law that voided Franklin's trust. But the state attorney general disagreed, arguing the money should be distributed through the entire state, not just one school. In the end, the courts sided with the Franklin Institute, and the school was awarded the full amount in 1994, according to Mental Floss.

Benjamin Franklin's fascinating way of distributing his money inspired other people to think about their legacy in the long term. According to Mental Floss, a millionaire named Jonathan Holden was inspired by Franklin's philanthropic spirit. He funded numerous trusts with nearly $3 million to be dispersed over 1,000 years, which could someday total $424 trillion. For now, Franklin's memory lives on in American history. And after many contentious fights, his money has been put to use in the two cities he loved most.