How Scandinavians Incorporate Witches Into Their Easter Celebration

In most parts of America, at least, the Easter holiday is a time for brightly-colored egg hunts and the Easter bunny. Halloween, on the other hand, is a holiday for young boys and girls to dress up like monsters and witches to go trick-or-treating. In parts of Sweden and Finland, though, aspects of these two holidays meet in the Easter witch tradition. This creates, in effect, a Halloween-like atmosphere during Easter, which is most often associated with springtime (via TIME Magazine).

Most aspects of modern Easter celebrations are a muddle of pre-Christian pagan tradition, observing the change of the seasons, and the Christian celebration of Christ's resurrection, as The Conversation explains. How do witches, then, relate to either one of those things? And why do young girls still dress up like witches for Easter in this part of the world — a tradition that's come to be known Påskkärring, or "Easter hags"? That explanation begins with the persecution of women and girls believed to be witches in Sweden, from the Middle Ages throughout the late 18th century (via FOLKLIFE Magazine).

Sweden's witch trials and their legacy

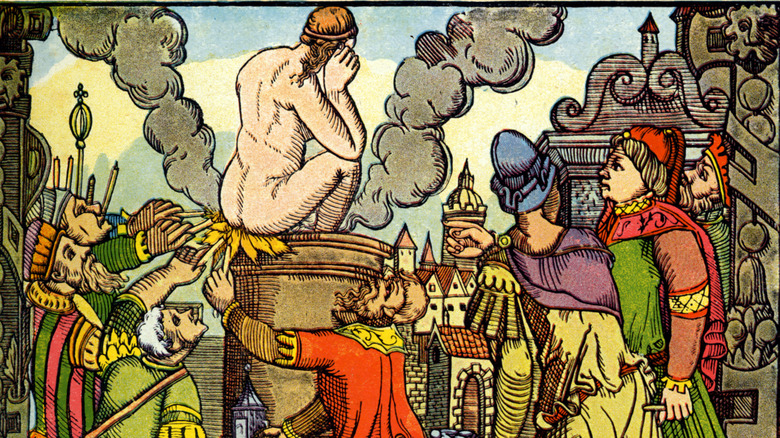

Much like the rest of Europe and even the American colonies, witch trials and executions were common in Sweden beginning around 1450. The death penalty for witchcraft was not banned in Sweden until 1780s, according to Nordiska Museet. Shortly after that time it's believed the Påskkärring tradition began throughout Sweden and even in parts of Finland. Prior to that point, witches were locked up until they could stand trial for Blåkulla, or taking the witches' sabbath, as it was called (via FOLKLIFE Magazine).

It's estimated, in fact, that up to 400 women and girls lost their lives to mass witch paranoia in Sweden during a time that's comes to be called "The Great Noise," beginning around 1550 and ending in the 1660s. Most often the women accused of witchcraft during this period were practicing herbalists or engaged in some other kinds of pre-Christian healing tradition. At that point, Christianity had spread all over Europe and so, too, had the Easter holiday.

Imprisoned Swedish witches and Maundy Thursday

Most often, Easter is often just one single day in many secular households. But Easter is, in fact, the culmination of a weeklong celebration called Holy Week, beginning on Palm Sunday in some Christian sects and running for seven days straight, concluding with Easter seven days later. Each day in between has significance all on its own, and one of those days has come to be called Maundy Thursday (via Britannica).

Maundy Thursday could be an anglicization of the Latin anthem "Mandatum novum do vobis." Maundy Thursday commemorates the day which Judas betrayed Jesus, and it's sometimes called Green Thursday, Clean Thursday, or Holy Thursday. In Sweden it's called Skärtorsdagen, per Real Scandinavia. Regardless of what the day is called, imprisoned women and girls awaiting trial or execution for witchcraft on this day were locked away extra tight in prison to prevent their escape.

What happens in Blåkulla stays in Blåkulla

In Sweden at the time, Blåkulla was not just the word for the Witches' Sabbath, it was also believed to be a place — or a mountainous island where Satan himself would gather all his witches around him to do witchy things. There are many theories today where Swedish people at that time may have believed Blåkulla was actually located (via Witch Awareness Month). On Maundy Thursday, it was believed Satan would break all imprisoned witches out of jail, and they would fly away on their broomsticks to Blåkulla, as TIME Magazine explains.

It wasn't just the local jails that received extra fortification on Maundy Thursday, either. Broomsticks were also kept out of sight to deprive any would-be visitors a means by which they could reach Blåkulla. Bonfires were also lit to scare away any witch who managed to get away as they flew on their broomsticks back home, per FOLKLIFE Magazine. There is, of course, no real place called Blåkulla. It's on this very notion, though — that imprisoned witches might escape on broomsticks to Blåkulla on Maundy Thursday — that the modern Påskkärring is based.

The Easter hags

Today, luckily, witch trials no longer take place, but the sad legacy of Sweden's witch trials lives on in the tradition of the Easter witch. One either the Thursday or Saturday prior to Easter, during Holy Week, young girls in Sweden and parts of Finland dress up like witches, wearing oversized skirts and shawls, traipsing door-to-door with kettles in search of sweets: chocolate eggs, in some parts of Finland, or simply a few coins in others.

Young girls painting freckles and bright red cheeks on their face is another common way in which Skärtorsdagen is observed in this part of the world. Even to this day, some households lock their doors tight during Skärtorsdagen to keep out the young witches and their devilish influence, according to This is Finland. Despite this dark history of this tradition, these days it's seen as a fun and family-friendly affair wherever Skärtorsdagen is observed, as Scandinavia Standard reports.

Skärtorsdagen in Finland

As This is Finland explains, there are some subtle differences to how Skärtorsdagen takes place in parts of Finland. In these areas, young girls often recite a poem, translating roughly into "I wave a twig for a fresh and healthy year ahead; a twig for you, a treat for me!" Springtime itself is also marked in some parts of Sweden for Skärtorsdagen by planting grass seed in shallow containers and watching them grow, or instead, sprouting birch twigs in water.

In parts of Eastern Finland, young witches roam most often on Easter Saturday, while in the west, it all tends to take place on Palm Sunday. Furthermore, the marriage of a Russian orthodox tradition involving birch branches with Easter hags shows the Russian and Swedish influences on Finnish culture. "This Finnish children's custom interestingly mixes two older traditions," Reeli Karimäki of the Pessi Children's Art Centre in Vantaa, nearby Helsinki, told This is Finland.