How Scientists Manipulate The Weather By Flying Planes Into Clouds

Is it possible to change the weather from an airplane? This is what scientists in Wyoming are doing to create more snow in the drought-stricken state, as CNN reported. They are accomplishing this through a process called cloud seeding. Cloud seeding is a method for getting a cloud to produce more rain or snow, Desert Research Institute explained. Clouds are formed when water vapor coalesces around a piece of dust or salt, otherwise known as a condensation nuclei. Condensation nuclei are the difference between pure water vapor and a raindrop or ice crystal, so injecting artificial condensation nuclei into the atmosphere can increase a cloud's ability to create rain or snow.

The Wyoming Weather Modification Program uses planes to cloud seed by flying into storms and unleashing cardboard casings full of silver iodide using flares, according to CNN. Silver iodide is a natural salt compound. "The reason it's used is because the geometric shape down to a molecular level is very similar to that of an ice crystal. And if you don't have that, you're not going to create additional ice crystals, which will then accumulate into snowflakes," Wyoming Weather Modification Program manager Julie Gondzar told CNN.

The beginning of cloud seeding

Cloud seeding was first discovered in 1946, according to the Santa Ynez Valley News. Vincent Schaefer was working at the General Electric laboratory trying to create clouds in a freezing room. He thought that his cloud-creation chamber wasn't cold enough, so he added some dry ice. Immediately, a cloud formed. It wasn't the extra cold that had made the difference, however. The water vapor in the room had condensed around the ice crystals. The concept was further developed with the help of physicist Bernard Vonnegut. Schaefer and Vonnegut discovered that silver iodide was a better cloud seed than dry ice crystals. Scientists have not been able to find another molecule that outperforms it since.

In 1947, government and industry leaders came together to form Project Cirrus to further research the potential of cloud seeding. However, the project ended in scandal when it used dry ice to attempt to weaken a hurricane, according to National Weather Service Heritage. After the seeding, the hurricane shifted course and made landfall in Savannah, Georgia, where it caused destruction. The project was canceled in disgrace.

Project STORMFURY

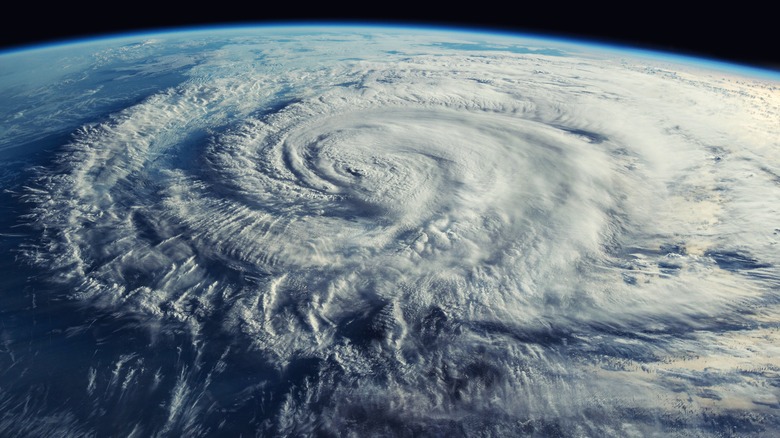

Project Cirrus wasn't the last time that scientists attempted to use cloud seeding to weaken hurricanes, however. The hypothesis was that seeding a hurricane would cause water droplets in the storm that existed in a liquid state at below freezing, otherwise known as supercooled water, to actually freeze, according to National Weather Service Heritage. This would disrupt the structure of the storm so much that the eye would have to reform and the wind speed would weaken by as much as 30% in the process.

To test this, the U.S. government formed project STORMFURY in the mid-1950s following a particularly active hurricane season. The idea was to fly planes into storms and seed them using silver iodide. However, the storms had to meet certain criteria. They had to have a less than 10% chance of making landfall in 24 hours; they had to be intense storms with well-formed eyes; and they had to be in range of an aircraft. The project seeded its first hurricane in 1961 and had its first supposed success in 1963 with Hurricane Beulah, when wind speeds fell by nearly 20% after seeding. However, it was difficult to find storms that met the project's criteria. Further, scientists eventually discovered that hurricanes did not have as much supercooled water as they thought, so seeding would not be as effective. The results of seeding didn't really alter naturally-occurring changes in storm intensity. The project ended in 1983.

Make mud, not war

The U.S. government has also used cloud seeding as a weapon. During the Vietnam War, the military secretly seeded clouds over Laos, North Vietnam, and South Vietnam in an attempt to induce rainfall for tactical purposes, as The New York Times reported. The program marked the first time that weather modification was used as a military strategy on a large scale, according to Gizmodo. The military hoped to lengthen the monsoon season and therefore cause flooding and landslides on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, which the North Vietnamese used to move troops and supplies. Between 1967 and 1972, Air Force pilots conducted around 2,000 runs seeding clouds. The pilots dubbed the project "Make mud, not war."

When the project was reported to the public in 1971, it generated a lot of controversial and was called the "Watergate of weather warfare." Congress passed a law in 1974 to prevent the military from using weather control in war, and a UN treaty followed, though it had many loopholes. There is also some debate as to how successful the program actually was, and it definitely turned the public against the idea of weather changing as a military activity. However, even before the project was revealed, some people were skeptical of government cloud seeding. When it rained at the Woodstock music festival in 1969, one attendee asked reporters "why the fascist pigs are seeding the clouds" (via AccuWeather).

Cloud seeding today

Today, cloud seeding is used for two main purposes: to make hail storms less severe and to mitigate droughts. The theory behind cloud seeding for hail storms is similar to that for hurricanes. By seeding clouds, scientists hope that their supercooled water will freeze at warmer temperatures and fall as rain or small hail instead of larger hailstones, Chemical & Engineering News explained. Cloud seeding is also used all over the world to try and generate more rain or snowfall for reservoirs or groundwater. It has been used abroad in Australia, Chile, China, France, Greece, India, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Canada, and Spain, as well as in the U.S. states of California, Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Nevada, North Dakota, Texas, Utah, and Wyoming, according to the Wyoming Water Development Office. Programs in states like Utah and North Dakota have been running since the 1970s and 1980s, while Wyoming's program began later, growing out of a study started in 2003, according to CNN.

It is possible to seed clouds from the ground as well as from the air. This requires the use of 20-foot generators that release aerosols into the air. However, using them to generate increased snowfall to boost mountain snowpacks is difficult, because the wind has to be blowing the right way in order to carry the seed over the mountains. Seeding clouds from airplanes is the most popular method.

Cloud seeding and climate change

Cloud seeding is becoming increasingly popular as drought increases because of the climate crisis. The UN estimates that nearly 50% of the world's population will be living in water-stressed areas by 2030 (via Chemical & Engineering News). Currently, around 61% of the continental U.S. is experiencing drought, according to CNN. However, there is still debate as to whether or not cloud seeding is an appropriate response to these water shortages. "It is possible that you're actually stealing water from someone else when you do this, because it may be, at least on a regional basis, a zero-sum game where if water falls out of the cloud in one spot, it's even drier by the time it makes it downwind to the next watershed," UCLA climate scientist Daniel Swain told CNN.

It has historically been difficult to accurately test the effectiveness of cloud seeding and to say that it definitely causes any extra precipitation that falls. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2020 was able to determine that cloud seeding had generated more snow than would have fallen otherwise. However, it only increases precipitation by as much as 10%, far from enough to end a drought, according to CNN. It could, however, help boost reservoir levels in some capacity. "It's not going to be the silver bullet, but it could be a helpful tool in a water manager's toolbox," scientist Sarah Tessendorf told CNN.