Military Experiments That Sound Made Up, But Aren't

When it comes to military research and experiments, there are a couple of different brands, so to speak. There's the devastating stuff, of course – the atomic bomb comes to mind, in this case. Then there's the disturbing stuff – the Cold War has plenty of that, even if you choose to discount the many, many times the CIA decided to dose unwitting subjects with hallucinogenic drugs. But then there's also the stuff that's just weird, the stuff that seems too bizarre to be real, the stuff that sounds more like it belongs in poorly conceived fictional stories rather than in the pages of history.

Nevertheless, a military experiment sounding absolutely absurd doesn't mean it isn't real. Far from it. There are plenty of times throughout history when a strange-sounding concept was legitimately given consideration by a nation's military or government, leaving people today to just wonder why. But, at the very least, the weirdness does provide for a pretty decent level of amusement. After all, who wouldn't find harebrained military experiments at least a little interesting?

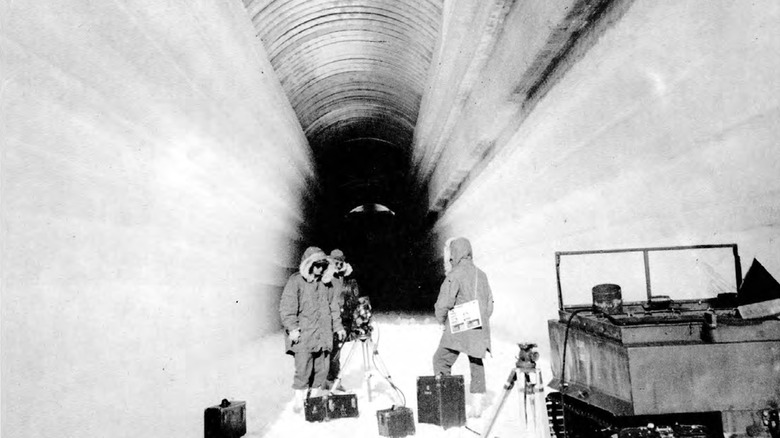

Project Iceworm

Back in the early 1950s, the U.S. and Denmark made a deal. Per Atomic Heritage, in effect, the U.S. (and other NATO countries) was allowed to build some military bases in Greenland. So, naturally, the U.S. military did just that, building a handful of different bases that served strategic purposes once the Cold War came around. Most of those bases were exactly what they were believed to be; Camp Century was not.

See, Camp Century had a secret. The camp itself was buried under the ice caps of Greenland, and it was actually a cover for something called Project Iceworm. According to History, the project was meant to hide miles of underground tunnels beneath the ice, as well as hundreds of nuclear missiles and thousands of missile silos. Ideally, those tunnels would be used to ship the missiles back and forth constantly, so that the Soviets could never actually be sure of the location of those missiles. (History actually likens the whole exercise to a game of nuclear "whack-a-mole," which is really pretty accurate.)

That said, the U.S. government tried really hard to keep everything under wraps, allowing groups to tour the entire city (which included a barber and library) that was housed under the ice, but leaning into the novelty, rather than the military secrets. That – the city under ice, not the nuclear silos – was all the American public knew about until the 1990s, though the project itself didn't really work, owing to the way the ice shifted constantly and destroyed the tunnels. Nor would it have lasted forever; The Guardian explains that global warming is actually melting the ice, exposing the decades-old city and nuclear facility.

Operation Acoustic Kitty

The 1960s were a tense time, to say the least. With the U.S. government desperate to get a leg up on the Soviets, the CIA set about creating more than a few weird and wild spy gadgets. Operation Acoustic Kitty was one of the stranger of those experiments; in effect, it involved making an actual, live cat into a spy. And a cyborg. Kind of.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the CIA did actually succeed in wiring up a cat with a listening device, embedding both a transmitter and battery beneath the skin (not the easiest task, by any means) as well as the listening device itself, inserting it into the cat's ear canal. Then, the cat would, ideally, be the most covert agent, able to freely roam and listen in on enemy agents, hopefully picking up some juicy Soviet secrets. But the cat being able to freely roam was both its greatest asset and fatal flaw. As anyone who's ever owned a cat knows, they're basically impossible to train and will do their own thing, regardless of what any human wants. The CIA learned that the hard way, after five years of research and an investment of $20 million, before it finally accepted that the cat would wander wherever and whenever it wanted. An official report summed it up simply: "cats are not especially trainable" (via History).

Not that it really mattered in the end. On the cat's first official training mission – listening in on two men sitting on a park bench – it wandered out into the street. Where it was promptly hit by a passing taxi and killed. Not the most glamorous of endings, for sure.

The U.S. Camel Corps

Look, horses are great and all, but have you ever considered: camels. What if, around the mid-1800s, the U.S. military just ditched horses and went with camels instead? Well, it did almost happen, for real. As told by the National Museum of the United States Army, the whole endeavor originated in the 1830s and was heavily tied to the westward expansion of the U.S. across the North American continent. Simply put, the large amount of materials needed for westward travel, especially when paired with hot temperatures, meant that camels could become ideal mounts for expeditions headed out west.

Initially, the U.S. army didn't take much note of the idea, but according to National Geographic, the concept did eventually catch the eye of Senator Jefferson Davis in the 1850s, who pressured Congress to fund the idea of folding camels into regular military operations. After a few years, he did actually secure some funding, insisting that the mounts could be used in campaigns to hunt down Native Americans. Which is pretty far from a noble pursuit, especially viewed through a modern lens, though Davis likely had other unsavory ideas in mind, too. Camels have an odd history linked to slavery, and, long story short, Davis might have been hoping that introducing more camels to the U.S. would lead to the westward expansion of slavery itself.

That didn't really happen, though. Camels weren't made for speed, but rather for carrying heavy loads, so they didn't really fare too well in battle. Plus, they had their own unique issues, not least of which was their unpleasant smell. Ultimately, they didn't see much military use, aside from a few token uses during the Civil War.

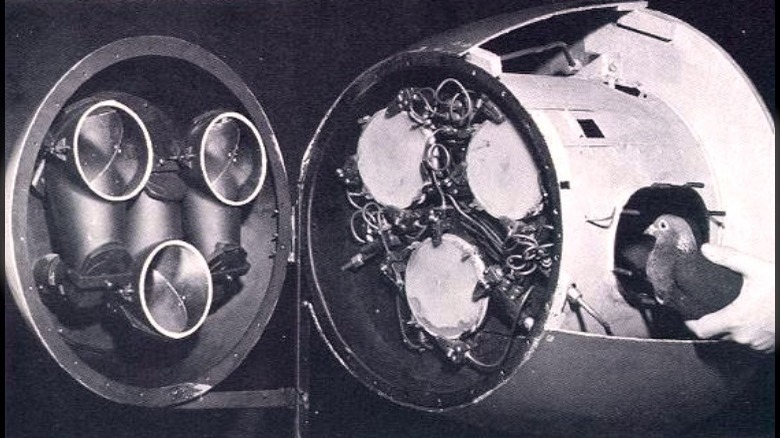

Project Pigeon

When you think of World War II, there's a good chance you think of the atomic bomb (among other things). But have you ever heard of the pigeon-guided bomb? Because that's not a joke – it's an honest thing that the U.S. military actually spent real money on. As explained by Military History, the entire project was the brainchild of Harvard professor Burrhus Frederic Skinner. Per Smithsonian Magazine, Skinner had already worked with pigeons in his own research, and said himself that he began to see them as "'devices' with excellent vision and extraordinary maneuverability." Given that the U.S. military was, at the time, having a hard time figuring out how to effectively and efficiently guide their missiles, Skinner saw pigeons as the answer to their prayers. After all, who said pigeons couldn't guide missiles?

The weirdest part of this whole thing: it actually worked. Three trained pigeons were housed inside the head of a missile and had learned how to peck at three different screens, their movements guiding themselves – and the missile – toward their intended destination. Initial tests were actually rather successful, but suddenly, the government funds stopped flowing in.

Skinner blamed the narrowmindedness of his benefactors, saying that the "problem was no one would take [him] seriously." Basically, the whole thing was just too weird. Which was probably part of the issue, but there might have been another factor, too. Namely, radar was in its early stages of development around the exact same time, and the military had decided to turn its attention toward that research instead. And given that everyday folk have heard of radar, not the pigeon-guided missile, it was probably a pretty good choice.

The 'gay bomb'

This one definitely sounds pretty odd. Just hearing that name, it's not exactly obvious what this thing was meant to do. So, in short, it was a bomb that was meant to turn soldiers gay. Which, well ... here's the story.

All That's Interesting explains that, in 1994, the U.S. Department of Defense was interested in finding less lethal ways to deal with enemy soldiers; specifically, they were looking for something to demoralize and temporarily debilitate them. So they turned to some strange chemical compounds, churning out a paper with the creative title of "Harassing, Annoying, and 'Bad Guy' Identifying Chemicals" (via Gizmodo). The gay bomb proposed in that paper would cost $7.5 million in development costs and "contained a chemical that would cause enemy soldiers to become gay ... because all [the] soldiers became irresistibly attractive to one another." Basically, through the magic of pheromones and aphrodisiacs, the lust and sexual tension would just be too much for these soldiers to handle, and the unit would cease to function. All because everyone thought everyone else was just so incredibly hot. Sounds like the plot of a bad romance movie.

Ultimately, this project never really got past the idea stage (though it did inspire other strange concepts, like actual stink bombs, or bombs that released a substance that angered local wasps into stinging affected soldiers). And it's maybe summed up best by Aaron Belkin, the director of the Michael Palm Center: "The idea that you could submit someone to some aerosol spray and change their sexual behavior is ludicrous" (via The Guardian).

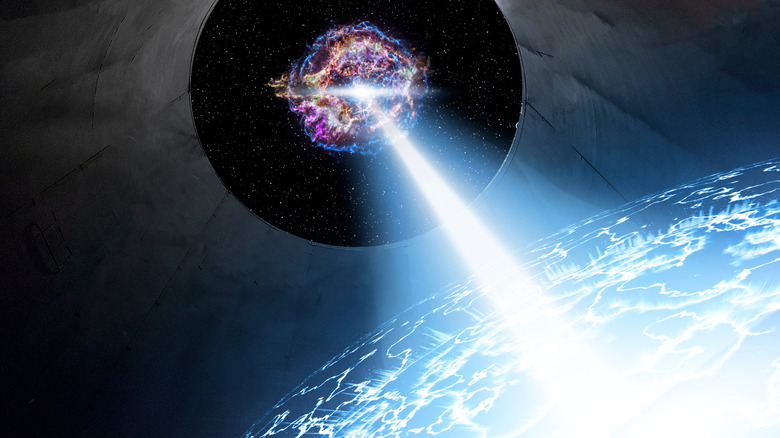

The Sonnengewehr

While the Nazi's "Sonnengewehr" translates to "sun gun" (via War History Online), it's maybe easiest to compare this particular hypothetical weapon to the Death Star. Because that's pretty much what it is, just on a smaller scale and based on the concept behind using a magnifying glass to light things on fire.

The Nazis definitely had some strange ideas for weaponry, but, per Mega Projects, this particular one originated in 1923 with a scientist named Hermann Oberth. The exact plans for this are vague – but that's not too surprising, between the fact that Nazi plans are hazy at best and the fact that this plan, conceived decades before Sputnik, involved a space station. In short, there were some complex plans for a space station that would orbit Earth and include a pumpkin garden as an oxygen source, as well as surfaces that would work with the astronauts' magnet-soled shoes. It would also include a massive mirror, which Oberth recognized as the "ultimate weapon" (via War History Online). The space mirror would be shaped such that it could reflect and concentrate the Sun's rays into, essentially, a Death Star-esque laser, directed to a single spot on the Earth's surface. As intended, the power of the Sun would utterly torch entire cities or even make the ocean boil.

Would this have worked? Honestly, probably not – the concept would likely need a lot of reworking to even kind of resemble what was intended, and that's not accounting for the ridiculous costs to pull off the construction. This whole thing is both massive and in space, after all; neither of those factors points to a cost-effective project.

The Antonov A-40

The strangeness of this one really doesn't require that much explanation. The Antonov A-40 was a tank with wings. Need more be said?

Don't fret; here's the story. As explained by The National Interest, one of the enduring problems of battle is getting troops and equipment down onto a battlefield. People can parachute, but dropping an entire tank into battle is tricky business – not technically impossible, but still awkward for a number of reasons. And in both cases, per Gizmodo, doing so could put potentially invaluable aircraft right into the enemy's line of fire, which would've been far from desirable in the heat of World War II. That's where the Soviet Antonov A-40 came in. Designed by Oleg Antonov and literally called the "winged tank," the A-40 consisted of the relatively lightweight T-60 Soviet tank outfitted with biplane-style wooden wings. It didn't have an engine of its own and needed to be lifted and pulled near the battlefield by another plane, at which point it would be released and glide down to the ground, the tank itself acting like landing gear. And the best part? The crew could ride inside the tank all the way to the ground – rather than having to parachute down separately – and steered it by moving the tank's turret.

As amusing as the idea of tanks flying down from the sky is, the A-40 never actually saw battle. It was only tested once, and while the test was technically successful – the pilot could glide the tank down without catastrophe – it brought a bunch of problems to light. Namely, the weight of the tank (even without ammunition) blew out the engine of the towing plane, meaning that scaling the concept up to work with more powerful tanks was more work than it was worth.

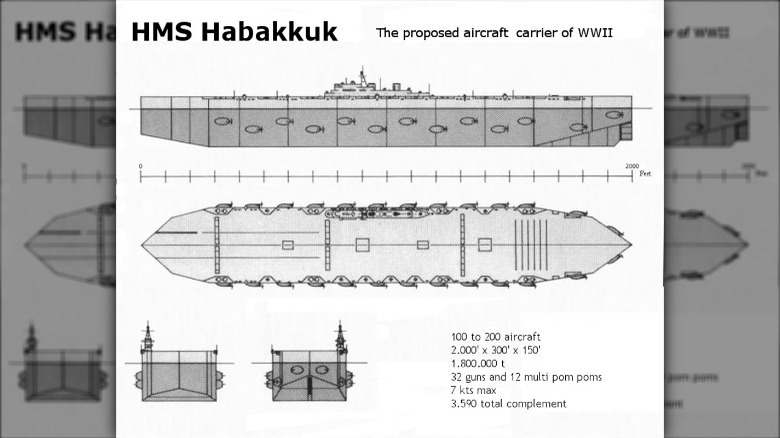

Project Habakkuk

It was the middle of World War II, and Britain was having some issues during the Battle of the Atlantic. First was the German U-boats, per CNN, notorious for stealthily wiping out whole naval convoys; second, was the lack of conventional building materials such as steel (via War History Online). Both factors together spelled bad news for the British, but Geoffrey Pyke felt he had the solution: an aircraft carrier made of ice.

It sounds like a joke, but the idea, codenamed Project Habakkuk, did actually have a leg to stand on. For one, ice isn't steel, so the lack of building materials wasn't a problem. But on top of that, icebergs had proven to be terrifyingly resistant to things like missile strikes and collisions with man-made things. (Everyone knows who won the battle between the Titanic and an iceberg, after all.) So Pyke's idea, essentially an iceberg topped with a landing strip for aircraft, was given the green light, even approved by Winston Churchill himself.

But once the clandestine research began in Canada's Lake Patricia, the problems started cropping up. The vessel would have to be massive, especially considering icebergs work by being mostly underwater, and as soon as the iceberg started melting, it could start to list sideways – not the most desirable feature of an aircraft carrier. Pyke came up with the idea of using pykrete (a frozen mix of wood pulp and water) since it would both be stronger and less liable to melt, but that would require a complicated mess of refrigeration units. And even then, the idea was too little, too late. Other new technologies (like radar) had solved earlier problems, and Project Habakkuk just wasn't needed anymore; the entire vessel was ultimately allowed to sink to the bottom of the lake.

Project X-Ray

World War II is especially well-known for the new bombs it introduced to the globe. Of course, the atomic bomb is the most infamous, but Project X-Ray was the codename for research on yet another bomb. So why haven't you heard of it? Maybe because this was literally a bat bomb.

The Atlantic recalls the story, which began on December 7, 1941 – the day that Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. Filled with righteous anger, a dentist named Lytle S. Adams had an idea to exact revenge: a small container filled with bats, each carrying a tiny, timed incendiary bomb. This bat bomb would be dropped over Japanese cities, releasing the bats, which would then roost in the roofs of local homes. At that point, the bombs could be triggered, setting the city ablaze before anyone even knew what was really happening. As he put it: "Think of thousands of fires breaking out simultaneously over a circle of forty miles in diameter for every bomb dropped." It sounds kind of insane, but Adams had friends in high places, including First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. She vouched for him, and his "bizarre and visionary" proposal was legitimately accepted by the National Research Defense Committee.

But the project also came with its own problems. The bomb needed to be cold, as the bats were intended to be hibernating while they were being transported – not exactly the easiest, and on top of that, getting the bats to wake up at the right time wasn't exactly reliable. Quite a few just ended up dying in the fall on a number of tests, per History. Still, there were a couple of successful tests, but the project was shelved in favor of a more promising one: the atomic bomb.

Project Star Gate

During the Cold War, there were a number of different races that the U.S. and the Soviet Union were involved in. There was the nuclear arms race, and there was the Space Race, of course. But there was another, lesser-known aspect of the Cold War as well – the psychic arms race. Yes, the two main superpowers during the late 20th century were both legitimately looking to employ psychic spies.

Soviet research into psychic powers stretches back pretty far when compared to the U.S. – back to the late 19th century, in fact (via "Unconventional research in USSR and Russia: short overview"). But when the U.S. government got word of this, they desperately didn't want to fall behind and started training psychics of their own – Project Star Gate, in more official terms. While there were a number of different facets of this whole thing, the U.S. was mainly interested in weaponizing ESP through the use of "remote viewing" – essentially, sitting down with some psychics and asking them to describe the details of one Soviet site or another, per the New York Times. And, the strangest thing was that there seemed to be some success with this method; psychics reportedly could view specific equipment and features of classified sites, which could only be confirmed through secret information. They were even used, at one point, to navigate a very real hostage situation, according to the Miami Herald, although that same incident implies that, maybe, the actual validity of this experiment should be taken with a grain of salt. Very few of their reports were accurate at all, and the whole endeavor was described as "a huge waste of time and money."