Notable Supreme Court Firsts Throughout History

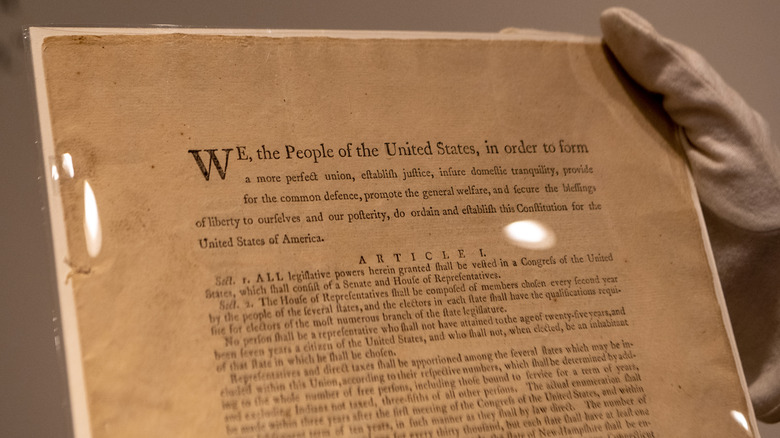

Carved into the imposing pediment of the massive neoclassical Supreme Court Building are but four words: "EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW." Indeed the Supreme Court is the highest and, in many cases, last bastion of law in the United States of America. It can be unnerving, then, to realize just how plastic the laws interpreted by the court can be, and how varied the practices of that august body have proven over the years.

Since its formation well over two centuries ago, far from being a staid, immutable, and objective arbiter of the law, the court has gone through numerous changes, dealt with its share of scandal, evolved in many ways, and failed to evolve in many more. Rights once considered forever enshrined by the Constitution are now moot, whereas others never considered in the early days of the American experiment are now guaranteed. And while intended to be the apolitical third branch of United States government, no one who has spent even a modicum of time watching the Supreme Court can pretend politics never play a role there.

As of this writing, people are watching the court to see whether President Joe Biden's recently announced nominee, Ketanji Brown Jackson, will soon make history as the first African American woman to sit on the highest court in the land, per CNN. But in the meantime, here are some other notable firsts in the history of the Supreme Court.

The first Supreme Court

According to Mount Vernon, Congress passed the Judiciary Act in the year 1789, thereby establishing the court system of the United States of America, including the Supreme Court. As president of the United States at the time, George Washington was in a unique position that, hopefully, no other president shall ever find himself or herself in again: He was obliged to appoint the entirety of the Supreme Court in one fell swoop.

At the time of its first establishment, the Supreme Court had six seats. To these positions, Washington appointed five associate justices: John Blair, James Wilson, William Cushing, John Rutledge, and James Iredell. And as the first chief justice of the Supreme Court, Washington selected John Jay. The court's first meeting took place in New York on Tuesday, February 2, 1790, a day later than originally selected based on travel delays. Only four justices were even able to attend the first sitting of the court — Chief Justice Jay and Associate Justices Blair, Cushing, and Wilson — but it was enough to constitute a quorum, thus the Supreme Court came into being. In the early years, the members of the court would convene for two sessions annually, meeting in February and in August. And as one might expect given the movement of the official capital city of the United States in the early years, at first the court met in New York, then, for most of the 1790s, it met in Philadelphia, the capital city for nearly a decade, per the Supreme Court, before finally being permanently settled in Washington, D.C.

The first Supreme Court ruling is issued

The very first opinion was handed down on August 3, 1791, two years after the court had been formed and a year and a half after its first seating. The case was West v. Barnes, according to the Supreme Court. The case of West v. Barnes was not the first ever docketed by the court, mind you — that was Collet v. Collet, which was dropped before a hearing took place — but it was the first ever decided there.

William West was a Revolutionary War general who, before and after the war, was a farmer based out of Rhode Island. In order to keep his underperforming farm functioning, he had taken out a mortgage on it in the mid-1760s, and in the mid-1780s, he was looking to finally pay off the remainder of the fees, which he did so using paper currency earned during a lottery West conducted, the right to do so having been granted by the state in light of his service in the war, per Ballotpedia.

Still with us? Well, David Barnes was not one to go along with all of this: Barnes was an heir to the family who had fronted West the money back in the 1760s, and he rejected payment in paper money, demanding gold or silver coins for payment instead. He brought a suit against West, who would lose the first court battle, then bring the case up the chain to the Supreme Court. After a good amount of legal wrangling and back-and-forth, West would lose the case, essentially due to procedural error, and he was eventually forced to give up his farm (via Case Text).

First amendment limiting court power

All students who come up through the American education system learn about those three branches of government — the legislative (meaning Congress), the executive (meaning the President and his or her larger office), and the judicial (meaning the courts) — and how each has a different role when it comes to the law, namely writing laws, enforcing them, and interpreting them, as laid out by the United States government's own reporting. So what happens when one branch, say, the courts, seem to be getting too much power? New laws get written to reel that power back in, and that's just what happened in 1794 when Congress passed the 11th Amendment (ratified in 1795), according to the National Constitution Center.

According to Cornell Law, the 11th Amendment reads: "The judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by citizens of another state, or by citizens or subjects of any foreign state." And what it aimed to do, as relayed by the Constitution Center, was limit how laws created in one area of jurisdiction were applied in others. In other words, if Maryland has a law against juggling oranges but you are fully at will to juggle any and all citrus fruit under Federal law, the Supreme Court need not hear a case regarding orange juggling. And further, just because a Federal law exists, state courts do not have to hear cases that may involve its violation. For example, were a Federal law to prohibit orange juggling, a Maryland state court would not be obliged to take up a case involving said citrus tossing.

First Supreme Court Justice to be impeached

In the late fall of the year 1804, preparations began for the first ever impeachment trial of a Supreme Court justice. And in fact, to date it remains the only case of impeachment of a Supreme Court justice (via Supreme Court). The man who would be impeached by the United States Senate that year was Justice Samuel Chase, according to the U.S. Senate. Per records kept by the Senate: "The House voted to impeach Chase on March 12, 1804, accusing Chase of refusing to dismiss biased jurors and of excluding or limiting defense witnesses in two politically sensitive cases." But the more accurate reasons that Chase faced impeachment were political considerations.

Chase was an outspoken Federalist and was at odds with the Jeffersonian Republicans then controlling the Congress, not to mention to presidency. While hoping to find Chase guilty of improper and biased interpretation of the law and thus remove him for apparently just cause, really, the trial managers, all members of the House of Representatives, just wanted Chase gone. Ironically, one specific charge leveled against the judge was that he often allowed his own political views to cloud his rulings.

When proceedings finally commenced that November of 1804, it was unclear how things would pan out for Justice Chase. As it happened, in January of 1805, Chase was acquitted on all counts; though a majority of those sitting in judgement voted him guilty on three out of eight of the charges leveled, a two-thirds majority was required for each charge to come to conviction. Samuel Chase would continue serving on the Supreme Court until his death in the year 1811.

First Supreme Court expansion

Nowhere in the Constitution of the United States of America is a set number of Supreme Court justices specified. Thus Congress is entirely within its rights to act to expand or to shrink the number of seats of that body, and while changing the size of the Supreme Court may be a "third rail" for some, a major bone of contention for others, and a clear objective of others, it's nothing new, any way you cut it. In fact, according to Harvard Law & Policy Review, the size of the court has changed seven times already over the years.

The first time the Supreme Court was shrunk was under John Adams, second President of the United States, who, in tandem with his congressional supporters in the Federalist Party, reduced the court from six to five seats in the lame duck session between Thomas Jefferson's election and inauguration, hoping to limit the incoming Republican POTUS's power to appoint a new judge to the highest bench. Not to be stopped thusly, Jefferson and the newly empowered Congress, the Federalists having lost seats, not only restored the sixth seat but soon added a new seventh justice to the Supreme Court as well.

The court would reach nine seats, the same number it has today, under President Andrew Jackson's watch in 1837. (And a 10th would be added by Lincoln, then later the court was shrunk to seven, then expanded again, and on it went.)

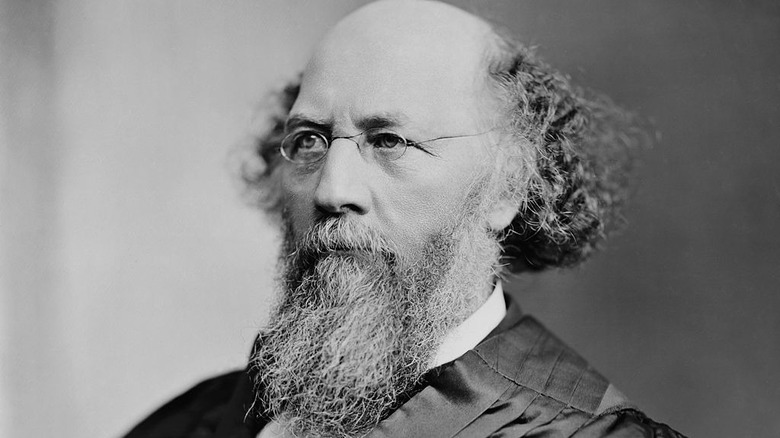

First assassination attempt on a Supreme Court justice

Say what you will about the life of a Supreme Court justice in terms of the morass of politics, infighting, reversals, activism, and so forth, but note this: it's a surprisingly safe life given all the contention or outright rage their work can cause among the populace. In fact, in all the many years since the Supreme Court first started handing down decisions, there has been only one credible assassination attempt on the life of a sitting justice, and it was essentially over a personal vendetta, not a matter related to a Supreme Court decision at all, according to a 2005 article published by the Journal of Supreme Court History. That justice was Stephen Johnson Field, one of the longest-serving Supreme Court judges of all time (via Britannica), given his 34 years on the bench.

In the year 1889, while still a member of the United States Supreme Court but acting in the capacity of a judge of the 9th Federal Circuit Court, Justice Field heard a divorce case in which he ultimately ruled against the husband, a former California Supreme Court judge named David Terry whom Field had actually replaced many years prior. Bad blood still simmered between the two men, which may or may not have contributed to Field, known for holding grudges and settling scores (he had carried pistols under his robes when younger, ready at any time to duel), ruling against Terry in the divorce case and temporarily jailing him for being in contempt of court.

An embittered Terry would soon after attempt to shoot Field, an assassination thwarted when Field's bodyguard shot Terry dead that fateful day, August 14, 1889.

The first Jewish justice

For the first 125-plus years of the existence of the United States Supreme Court, all of the people who served as justices had at least three things in common: they were men, they were white, and they were Christian. At least one of those metrics finally changed with the accession to the bench of Louis Dembitz Brandeis, who would become the first Jewish member of the Supreme Court when he was appointed in the year 1916, according to Britannica.

And frankly, it would have been preposterous had Brandeis not made it onto the highest bench, his politically contentious outspoken support for Zionism — the creation of and support for a Jewish homeland in the traditional Holy Land — notwithstanding: he was, quite simply, perfectly qualified. Brandeis, whose well-educated and cultured parents had emigrated from Prague to Kentucky in 1849, seven years before the birth of the future judge, graduated from Harvard Law School at the top of his class in the year 1877 and went on to practice law for many years. As a lawyer, he often took on cases supporting the rights of workers previously powerless to stand up to large corporations; once on the Supreme Court, Justice Brandeis supported free speech and sought to restrict governmental overreach, both at the state and federal levels.

He would serve until February 1939, according to Brandeis University, the school named for the vaunted justice, retiring just two years before his death, in 1941, at the age of 84. Brandeis was a Supreme Court judge for more than 22 years.

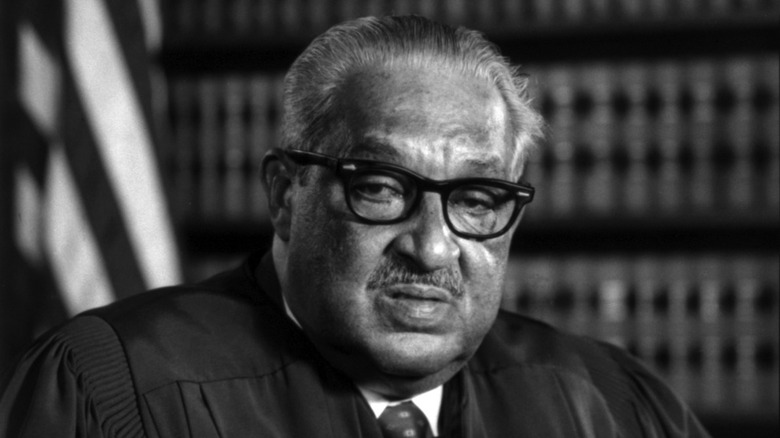

The first Black justice

The 1916 appointment of Louis Brandeis was a good step for the Supreme Court in terms of finally breaking the 100% male, white, Christian makeup of the court, but it would take another half a century until that second metric was finally upended. In fact, it would take 51 years, to be precise, for it was in the year 1967 that Thurgood Marshall became the first African American justice to join the highest court in the land, according to the National Archives Foundation.

Marshall was born and raised in Baltimore, Maryland, a city that, at the time of his youth in the 1910s and '20s, had a death rate more than twice as high for Black people as for white people, according to Oyez. The hardships, unfairness, and indeed the outright dangers Marshall saw his fellow African-Americans face in everyday life made a hard and fast impression on him, later guiding him as he practiced civil rights law after earning a law degree from Howard University, where he graduated at the top of his class in 1933 — a position that seems helpful when minorities want to ascend to the highest court. Marshall was invited to attend Harvard University for post-graduate studies but, eager to begin practicing law, he returned to Baltimore and opened a practice.

After handling myriad cases over many years, Marshall finally got the chance to take on a truly momentous issue when he argued on behalf of the plaintiffs in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education, per US Courts. When President Lyndon B. Johnson nominated Marshall to the high court a little more than a decade later, few could credibly argue he was not an apt choice. He would serve until his retirement in 1991, and he was succeeded by another justice of color, Clarence Thomas, still a member of the court as of this writing.

The first woman justice

14 years after Thurgood Marshall broke the color barrier of the Supreme Court, finally the gender barrier was breached as well. It had only taken a little less than 200 years for that to happen. The barrier breaker was Sandra Day O'Connor, according to Britannica, who joined the high court in 1981. O'Connor was born in Texas in the year 1930 and would go on to receive both an undergraduate degree as well as a law degree from Stanford University, but despite her abilities and educational pedigree, she found difficulty gaining employment as a lawyer, it being the 1950s and she being, well, a woman.

O'Connor eventually took a job as a deputy district attorney for a city in California but soon moved to Germany with her husband, fellow Stanford grad John Jay O'Connor III, per Oyez. Back in America in the later '50s, she opened a private practice in Arizona; then a few years after that, she became the assistant district attorney for the state of Arizona. O'Connor next moved into politics, filling a vacant seat in the Arisona state senate before winning several terms to elected office in that same body, of which she became majority leader.

O'Connor finally hit her best stride when she became a judge of the Superior Court of Maricopa County, Arisona, in 1975, setting herself up for a career that would remain in the judiciary from then on out. Soon appointed as a state supreme court justice, O'Connor had caught the attention of President Ronald Reagan, who nominated her to the United States Supreme Court in 1981, according to the Supreme Court. She would serve until early in the year 2006, her tenure marked by a staid, scholarly approach to jurisprudence.

First case to rule in favor of gun rights for individuals

If ever there were an example of a 27-word sentence causing more consternation than Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States of America, it would be hard to find. The Second Amendment, via the Constitute Project, reads in full: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed." So what's not to be infringed there? The establishment of a militia? When necessary for security only, or at all times? Arms at all times, or only when the "free State" is at risk? And is it infringement to limit any form of arms?

During most of the decades of court history, the answers to such questions were so unclear that cases dealing with Second Amendment rights were generally avoided, and when heard, often the ruling restricted — rather than expanded — rights relating to gun ownership, as when United States v. Miller restricted shotgun with short barrels, according to Cornell Law, or when United States v. Warner ruled that no, Jesse Warner did not have the authority to own and transport machine guns, via Case Text. Then came the case of District of Columbia v. Heller in 2008 (via Justia). The Primary Holding of that case was that: "Private citizens have the right under the Second Amendment to possess an ordinary type of weapon and use it for lawful, historically established situations such as self-defense in a home, even when there is no relationship to a local militia."

In effect, the case said go ahead, get a gun — or two or three or ten — and have it at the ready for any reason at all, no reason needed.

The first Latinx justice

Yet another barrier was broken when Sonia Sotomayor joined the Supreme Court in 2009: she was the first justice of Hispanic (or Latinx) heritage to sit on the high court, per Oyez. Fitting, isn't it, that she was nominated to her position by the first African American president of the United States, Barack Obama? And indeed it was fitting that she was nominated and confirmed, given her experience and abilities.

Sotomayor, born in New York City in 1954, would go on to be a high school valedictorian, attend Princeton University for her undergraduate studies, and then to go on to law school at Yale, according to the National Women's History Museum. Upon graduation from Yale Law, Sotomayor returned to New York where she was made an assistant district attorney while only in her mid-20s. A fearless prosecutor, the young woman went toe-to-toe with hardened criminals and major white-collar crooks alike. She then went into private practice for a number of years before becoming a judge on the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York in 1991, having been appointed by President George H. W. Bush, Sr.

Sotomayor served in this capacity with aplomb — most notably when she helped settle a major dispute between Major League Baseball players and team owners in 1995 (via Justia) — before being elevated to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit by President Bill Clinton in 1997. Often the last stop before the Supreme Court (via Ballotpedia), for judges and for cases, this post burnished Sotomayor's credentials even further, and when she was nominated for the high court a little more than a decade later, she was approved in a Senate vote by a more than two-to-one margin.

First Black female nominee

Ideally, by the time this writing is seen by most readers, Ketanji Brown Jackson will be properly referred to as Supreme Court Justice Jackson, but regardless she will always have a place in history, for as of early 2022, Jackson has become the first Black woman to be nominated to the United States Supreme Court. According to the White House, Jackson was nominated by President Joe Biden to fill a seat being vacated by retiring justice Stephen Breyer, for whom Jackson had clerked in the late 1990s. That was Harvard Law, for the record, where Jackson served as an editor for the vaunted "Harvard Law Review." She also attended Harvard for her undergrad studies.

Freshly out of law school, Jackson clerked for judges of the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit (via Congressional Research Service), and she spent a brief time in private practice. She would then go on to serve as a public defender for a number of years before moving into the judiciary, where she has served since her confirmation in 2013, having been nominated to the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia by President Obama in 2012.

Ketanji Brown Jackson's historic nomination marks the fulfillment of a Biden campaign promise to select a woman of color for the court (via NPR); fortunately, Jackson is also an eminently qualified and capable person, background and gender notwithstanding.