Dog Breeds That Sadly Went Extinct

The American Kennel Club currently recognizes 199 different dog breeds, while the Fédération Cynologique Internationale recognizes 354 breeds. Both those numbers are in flux, though, because there are lots of other dog breeds in the world — maybe even hundreds — some of which will eventually gain recognition from one or both organizations. Others, though, will remain unrecognized, not because they aren't legitimate breeds but because they're rare, there's no breed club, their breeders don't bother with pedigrees, or just because they're not the right sorts of dogs for dog shows.

Humans have been breeding dogs for thousands of years, selecting for useful qualities and selecting out undesirable ones. And since "useful" means something different to a person who lives in the Arctic Circle than to someone who lives in central China, well, humans have had a lot of time to create a lot of different breeds. Some, like the Saluki, have been around for millennia and are still being bred today (via American Kennel Club). Others, like the American Hairless Terrier, have only been around for a few decades.

Still others enjoyed a long and prosperous partnership with humans until one day, they just disappeared. We can find some of these dogs in paintings and old texts, and we are lucky enough to have photographs of a few of them. But for the most part, these dogs are gone, never to play fetch, chase sticks, or be Very Good Dogs ever again. Here are just a few of them.

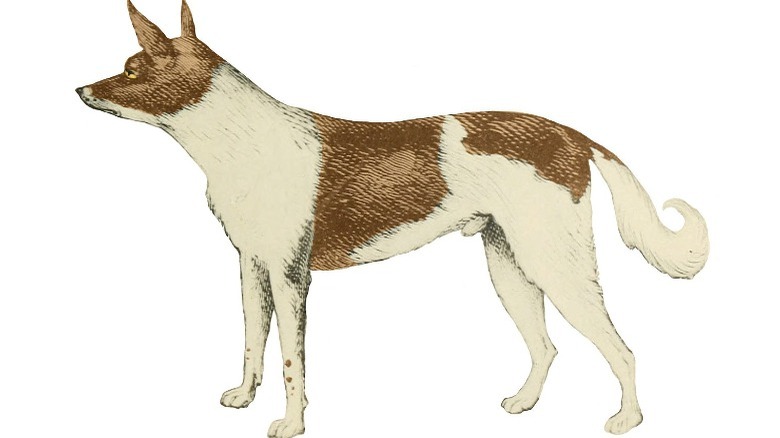

English water spaniel

People have been hunting with dogs since before guns were even a thing. Hunting dog types differ based on what they do in the field — in the early days, spaniels were divided into two categories: land spaniels and water spaniels. Land spaniels could be springers or setters. Setters found game on the ground and then crouched so hunters could catch it with a net (via Gundog Journal). Springers, on the other hand, flushed game so hunters could shoot it as it fled.

The English water spaniel was one of those early springer-type dogs. It was first mentioned in 1607 and continued to appear in dog books through the 19th century (via Ria Horter). It had a curly coat that some authors described as "like a poodle" and was white and liver-spotted like a modern springer spaniel, though paintings indicated that it could also be white with tan, brown, or orange patches. English water spaniels were prized for their ability to retrieve as well as flush; in fact, one author said the breed could "swim and dive as well as the ducks."

Despite its early popularity, the breed was in decline by the early 1900s, and by 1967 one author noted that "none has been seen for over 30 years." Rita Horter notes the breed is truly extinct because, unlike the also-disappeared Norfolk spaniel, it was not simply reclassified as a "sporting spaniel" when the Sporting Spaniel Club was established in 1885.

Hare Indian dog

Despite the name, the Hare Indian dog did not come from India, but rather from the Northeastern Territories of Canada, where it was bred by the indigenous Hare people. According to Song Dog Kennels, the breed was used by the Hare and other indigenous groups to check traps and help pack animal skins, hence its alternate name "trap line dog." Hare dogs could also climb trees and were sometimes used to retrieve treed game or even birds from places too high for humans to reach.

Hare dogs were described as having long, slender muzzles and thick, pointed ears. They were mostly short haired with longer hair around the shoulders and face. Early authors marveled at their resemblance to coyotes and suggested that they may have been directly descended from them. Part of the reasoning was their appearance, but Hare dogs also sounded like coyotes — the 1873 book American Naturalist described "a few, short, sharp barks followed by a prolonged shrill howl" and noted that Hare dogs would often leave their homes during the breeding season, possibly in pursuit of coyote mates.

Hare dogs are extinct, but their bloodlines can still be found in modern American Indian Dogs. You won't find American Indian dogs in the AKC book, but they do have a growing following of enthusiasts.

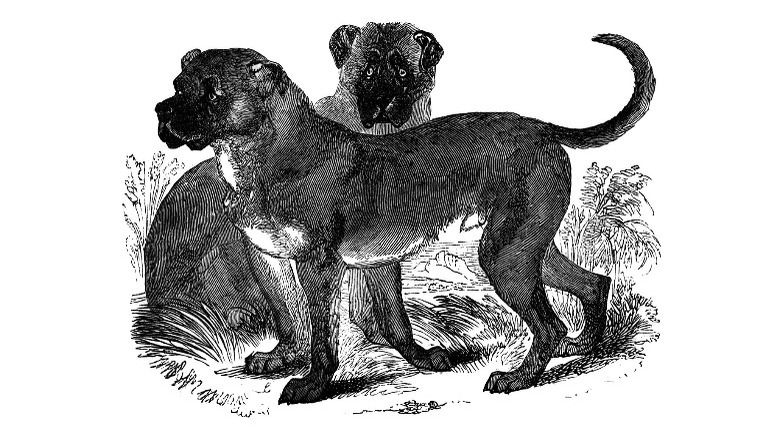

Bullenbeisser

The translation of Bullenbeisser is "bull biter," and yes, the name was literal. According to Dog Breed Standards, Bullenbeissers were used for bull-baiting, a "sport" that became popular in the middle ages and was still a thing up until it finally started occurring to people that it was cruel and horrible, which didn't happen in most places until the 19th century. Anyway, bull-baiting pitted an 80-pound dog against a one-ton bull, you know, just for laughs. Bulldogs like the Bullenbeisser were trained to latch on to the nose of the staked bull and hang on until the bull fell over (via Cesar's Way). Obviously, this was dangerous for both bull and dog — the dog would be shaken violently and if it wasn't able to hang on, it would be trampled, gored, or simply smashed into the ground.

The Bullenbeisser was imported into South Africa in the late 1600s, where it was used as breeding stock to produce dogs like the Rhodesian Ridgeback and the South African Boerboel. Its contributions to the boxer breed, though, are probably its most famous: Dog Breed Standards notes that modern boxers are said to be roughly 70% Bullenbeisser and 30% English bulldog. The Bullenbeisser itself, though, no longer exists. Ultimately, the breed was kind of just swallowed up by its progeny. As breeders started getting the types of dogs they were breeding for, it was no longer necessary to add more Bullenbeisser blood and the breed was slowly replaced by its own offspring.

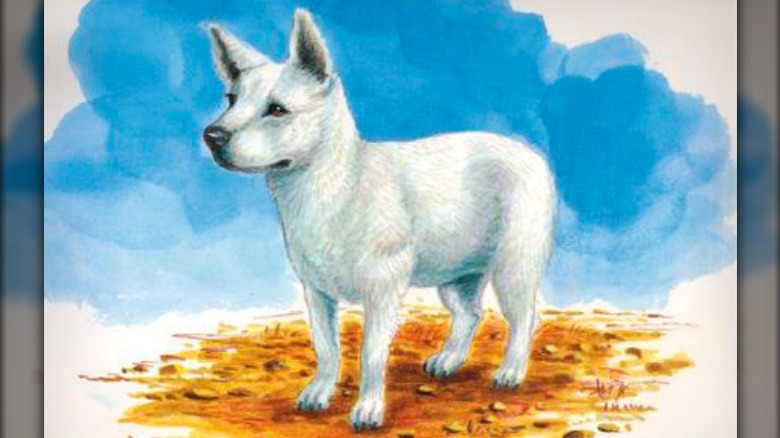

Hawaiian Poi Dog

Poi is a traditional Hawaiian staple food made out of pulverized taro root. The Hawaiian poi dog has a similar name because it was fed poi and because it was essentially raised as livestock. Pre-European Hawaiians relied on fish for most of their animal protein, but they also raised chickens, pigs, and dogs to be eaten on special occasions (via Natural History of Hawaii).

The poi dog vaguely resembled a corgi, only with much shorter hair and slightly longer legs. It was described as "long-bodied" with pointed ears and a yellow, brown, or white coat. It was also "barkless."

The poi dog was extinct by the 20th century, mostly because it interbred with western dogs when Europeans started colonizing the islands. Today, when Hawaiians refer to "poi" dogs, they're talking about mixed-breed or "mutt" dogs (via For Kaua'i). The poi dog probably does still exist somewhere in the genes of modern Hawaiian dogs, but the breed itself has vanished. According to Honolulu Magazine, in the 1970s a Hawaiian zoo tried to bring back the poi dog and appears to have had some success (at one point at least 19 dogs were part of its breeding program), though the project kind of just ended at some point a few years later, so it either wasn't sustainable, the project lost funding or, more likely, the people involved just lost interest.

Fuegian Dog

Fuegian dogs were domesticated by an indigenous South American group called the Selk'nam, who lived in the Tierra del Fuego region of southern Patagonia. According to Chimu Adventures, the Selk'nam suffered a fate that you'll find pretty familiar — they were mostly wiped out by European settlers, though a few of them lived into the 1970s.

Their dogs went extinct long before they did, so not much is known about them except what's written down in a few descriptions penned by Europeans who interacted with the Selk'nam. One of these described Fuegian dogs as noisy and aggressive and also "acrimonious and irreconcilable" (via Ecology and Evolution), which makes sense since the Selk'nam used them for hunting and protection. The writer also said a person could "easily mistake them for a big fox," which is interesting because scientists now think that Fuegian dogs weren't descended from wolves like their European counterparts. The authors of a 2013 study published by Quaternary International extracted the DNA of a taxidermied Fuegian dog and compared it to the DNA of Patagonian culpeo foxes and found that it was 97.57% similar. This means the Fuegian dog wasn't a dog at all, but a domesticated fox.

It's worth noting, though, that despite its appearance the culpeo fox isn't really a fox. It is a member of a different genus than wolves and dogs but is in fact more closely related to them than it is to a true fox (via Canids of the World).

English white terrier

Today, terriers are mostly just lapdogs or, depending on your perspective, yappy lapdogs. But there was a time when a terrier was a working dog just like a sheepdog or a guard dog (via K9 Magazine). People bred them to be small so they could hunt small game like rabbits and sometimes so they could control vermin like rats and mice. Move over, kitty.

During the early 1800s, different terrier breeds were in development all over Europe, and every country seemed to have its own version. In England, it was the English white terrier, which in appearance was similar to a modern bull terrier only with a much more slender nose. In portraits, the dog often has cropped ears and a tail that curls at the tip. By the mid-1800s, everyone from chimney sweeps to royalty had an English white terrier. There's even a portrait of one entitled "The Royal Rat Catcher." But then dog shows came along and people decided they wanted their animals to look a little more refined. According to writer David Hancock, along with a ban on ear-cropping, this discouraged breeders from joining the dog-show fun and may have contributed to the eventual decline and extinction of the breed.

Some dog fanciers have advocated for bringing the English white back, suggesting you might get a similar dog by crossing a whippet to a bull terrier and/or a Manchester terrier. For now, though, the English white remains a memory of England's dog-breeding past.

Tahltan Bear Dog

The indigenous people of North America had their own dog breeds long before Europeans arrived, and Europeans cared as much about preserving those old breeds as they cared about preserving the cultures they came from. Today, though, there's some renewed interest in bringing back indigenous breeds. One of these is the Tahltan bear dog, which was originally bred and owned by the Tahltan First Nations in northwestern British Columbia.

According to Yukon News, Tahltan bear dogs were fox-sized with pointy ears and bushy tails. Writer Murray Lundberg says the Tahltan carried their dogs around in moosehide backpacks, much like childless people carry their chihuahuas around today, except bear dogs actually did useful things when they got to their destination, you know, besides just trembling and looking pathetic and/or adorable. The dogs were called bear dogs because, despite their diminutive size, the Tahltan would often use packs of them to hunt bears.

Like so many other extinct breeds, some breeders are trying to bring back the bear dog. There are even a few selling "bear dog" puppies, though it's unclear how much actual bear dog blood is in these very expensive animals. Murray argues that even if you could breed a dog that looked like a bear dog, you could never truly bring the breed back since it would have to be developed under the same conditions as the original. Colonization and modernization have made it impossible to recreate those conditions, so the bear dog will almost certainly remain extinct.

Salish wool dog

If you have a long-haired dog, you've probably joked that your pet loses so much hair, you could make a sweater. Most people, though, wouldn't actually want a sweater made out of dog hair. Think how it would smell if you got caught out in the rain.

According to Hakai, the indigenous people of the Pacific Northwest bred a certain type of small, wooly dog for its fur, and not in the same way you'd breed an Afghan or a Maltese terrier for its fur in that the fur wasn't meant to be left on the dog. Salish wool dogs were kept in packs on islands so lesser animals couldn't interbreed with them, and they were fed a special diet of fish and other types of meat. Twice a year, indigenous women would shear them like sheep and use the fur to spin yarn, which would be woven into blankets.

Many European travelers recorded the existence of wool dogs, but for a long time, no one could find physical evidence that indigenous people in the area had ever made blankets out of dog hair. More recently, though, researchers have identified dog hair in a few old blankets, but so far haven't found any made entirely from dog hair. Some think that's because it would have been hard to make a blanket out of dog hair alone, just based on the fact that dog hair doesn't have the natural "hooks" that make sheep's wool stick together.

Talbot

When it comes to tracking, today's bloodhound rules. The bloodhound has ridiculously long ears and is known for its excellent sense of smell. It also has a pretty sordid history as the favored dog for finding and subsequently tearing apart runaway slaves (via Black Voice News), so there's that.

According to National Purebred Dog Day, bloodhounds, basset hounds, and foxhounds are all descended from the talbot, a huge, white dog with bloodhound-like ears that could kill a stag all by itself. The talbot was a very old breed that probably originated in France and arrived in Great Britain with Normal conquerors in 1066. Like the bloodhound, it was prized for its determination and sense of smell. In the Middle Ages, it was used to track criminals, catch prisoners, and just outright kill people on the battlefield.

Up until the 18th century or so, the talbot was an aristocrat's dog, which might have something to do with the fact that the breed vanished shortly thereafter, because there just aren't that many aristocrats, at least not compared to the "common" people who kept sheepdogs and other working breeds out of necessity. No one knows how and when the talbot finally disappeared — early dog show organizers expected to attract talbot breeders but evidently, no talbots ever showed up. The breed vanished without most people even noticing.

Alpine Mastiff

The mastiff is one of the oldest dog types in the world. In fact, according to the Mastiff Club of America, there's evidence the Babylonians were using them to hunt lions 4,500 years ago. The Romans also used them to guard prisoners and (of course) fight in the arena, because in Roman times just about everything with a backbone had to fight in the arena. Centuries later Henry VIII gave 400 mastiffs to the king of Spain as a good-neighbor gift.

Some sources say the alpine mastiff was just rebranded as a St. Bernard, but the two breeds were actually distinct from each other. According to an 1866 book titled "The History of the Mastiff, Gathered from Sculpture, Pottery, Carving, Paintings, and Engravings; Also From Various Authors, with Remarks on the Same" (because authors in 1866 loved to give their books unnecessarily long names), the alpine mastiff was very different in appearance from the St. Bernard, though former almost certainly contributed to the bloodlines of the latter. The author describes the few alpine mastiffs that were still around in the mid-1800s as either "milk white" or brindled, and notes that they had long hair and were among the very largest mastiffs of the time. The author also speculates that St. Bernards were probably originally a sheepdog cross. There's nothing in the book to mark the extinction of the breed, but it's clear it was a rare dog at the time of publication, if not already extinct.

Dogo Cubano

"Doggo" is an affectionate name for any dog, typically those that appear in social media posts authored by people whose dogs are their surrogate children. So you might be tempted to love the dogo Cubano just based on its scrunchable, smooshable, scritchable name. Truthfully, though, the dogo Cubano was a huge, scary, vicious beast, which was bred exclusively by Spanish colonists for controlling the enslaved. According to the dog history website Jackal's Old Country Blood, the dogo Cubano was also called the Cuban hellhound on account of the fact that when it found its quarry, there was no smooshing or scritching because the dog was likely to just tear the person apart and eat them. Evidently, dogo Cubanos were also prone to accidentally killing kids and adult bystanders because they weren't always so great at metering their bloodlust.

The dogo Cubano was a mishmash of different Iberian breeds, including the Spanish bulldog, the Spanish mastiff, and various types of hounds. It seems like there wasn't much of a standard for the breed, though. Some were supposedly up to 150 pounds while others were a mere 75. Breeders didn't seem to care much, since the smaller dogs could be used for tracking slaves over long distances, while the larger ones could be used to control the slaves who weren't fleeing for their lives. So yeah, even though this is a list of dogs that "sadly," went extinct, maybe you don't need to be sad about all of them.

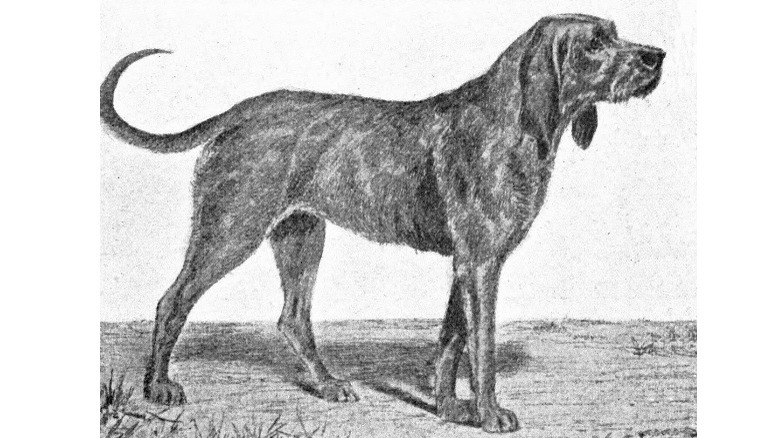

Chien-gris

In the 16th century, the English poet George Turberville translated "Chien-gris" to mean "dun hound," which is like the most boringist name for a dog breed since ever. A "golden retriever" is at least kind of shiny and a "chocolate lab" sounds like someone you'd want to make dessert plans with, but a "dun hound," well, yawn. Maybe that's why this dog doesn't exist anymore — it was grayish brown and probably faded into every background it was ever in until it was finally forgotten.

According to National Purebred Dog Day, the Chien-gris originated in the middle ages and sort of resembled a modern bloodhound. In the 19th century, the author of a dog book titled Dog Fancier's Companion said the best dun hounds were the ones with black backs and freckled legs, so just in case you didn't believe the preceding theory about boring color as the breed's undoing, well, there you go.

The book also said dun hounds were "good for all chases, and therefore of general use." And you know what they say ... a Jack-of-all-trades eventually goes extinct. The dun hound did contribute quite a lot of its genetics to the modern bloodhound but the original breed was sort of crossbred out of existence, though National Purebred Dog Day says its extinction also had something to do with the French, who evidently changed their mind about what sorts of hunting dogs they liked. Maybe they preferred dogs that they could actually find against a gray background.

Tweed water spaniel

The golden retriever is one of the most popular dog breeds in America. In fact, according to the American Kennel Club, in 2020 it was the fourth most popular breed, right behind German shepherds and, for some reason, French bulldogs. (In case you're wondering, Labrador retrievers topped the list that year.) Golden retrievers owe their existence and popularity to a now-extinct breed called the Tweed water spaniel, which originated in Scotland near the River Tweed (via National Purebred Dog Day). The Tweed water spaniel was itself a descendant of another extinct breed (the water dog San Juan) and various local water dogs.

According to the Clan Marjoribanks Society, it was a Marjoribanks ancestor named Dudely Coutts Marjoribanks who turned the Tweed water spaniel into the golden retriever. The foundation golden retriever stock was a litter born to a Tweed water spaniel by a wavy-coated retriever, and history even remembers the names of the offspring: Crocus, Cowslip, and Primrose. Today, golden retriever fanciers still hang out at the ruins of the old house where Dudely Coutts Marjoribanks bred the first golden retrievers, mostly so they can take fabulous photographs of like a million golden retrievers frolicking in front of the crumbling house.

Like so many other extinct breeds, the Tweed water spaniel was a victim of its own genetic success. People loved golden retrievers so much that they were no longer interested in the dog that founded the breed (via Dogell).