The Untold Truth Of America's First Serial Killer

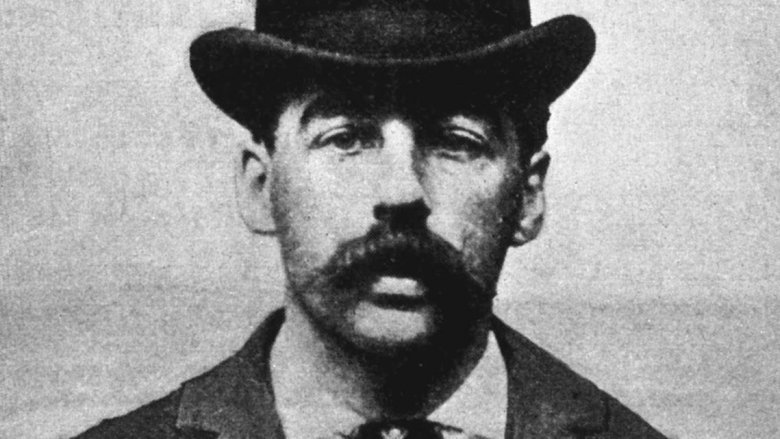

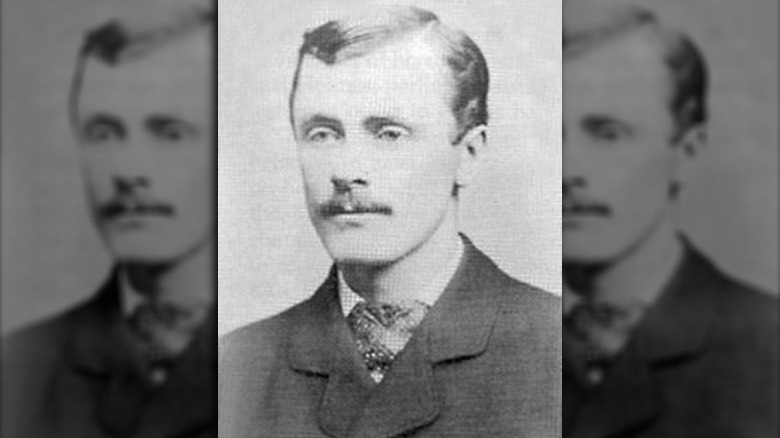

People have been killing each other probably since they learned to pick up rocks, but it's H.H. Holmes who has the dubious honor of being called America's first serial killer. You've probably heard the name, but it was just one of many aliases: His name was actually Herman Webster Mudgett, and he was born in New Hampshire in 1861. It wasn't until 1885 that he moved to Chicago, started using the H.H. Holmes alias on a regular basis, and began construction on his infamous Murder Castle. No one is sure how many people met their grisly end at Holmes' hands, but what is known about him is equal parts bizarre and terrifying. Here's the untold truth of America's first serial killer.

He blamed a childhood experience on his obsession with anatomy

H.H. Holmes was born in Gilmanton, New Hampshire, and most of his childhood history comes from his own accounts. When Holmes penned his autobiography, he obviously did so with a pretty strong bias. While it can't entirely be trusted, it can be used to test the waters of his strange tale.

According to Holmes, his parents were strict Methodists. He had a particularly strong bond with his mother and a father who would beat him — or send him to the attic — for misbehaving. He also wrote of one day in particular he said shaped his dark fascination with the inner workings of the human body. Growing up, he said, he had a fear of the town doctor's office. He said every time he walked by the open door and the smell wafted out at him it would turn his stomach. A few of the neighborhood bullies noticed and dragged him in. The boys forced him to touch the doctor's skeleton, and it's been speculated that was the moment that sparked something morbid and ultimately led to his enrollment in medical school (via Fosters).

There's one more odd thing of note about his time in Gilmanton — he spent a single term teaching in one of the local schools.

The killing may have started when he was 11

There's no way to tell just how many people H.H. Holmes killed; estimates range from 20 to 200 (via Biography). He confessed to 27 murders, but according to research done by Concordia University and published in Forensic Scholars Today, he told his lawyer he had killed 133 people, and Chicago police reportedly found the remains of at least 100 individuals in his Murder Castle alone.

According to researchers, his taste for killing started when he was young. Holmes would reportedly flee his abusive household for the nearby forests, where he passed the time by dissecting animals (beginning with lizards and escalating to dogs). They also suspect he may have killed his first human when he was 11 — he at least witnessed the death. He had "befriended" a slightly older man named Tom. According to Holmes, they had been exploring an abandoned house when Tom took a fall and was killed. Some believe Holmes pushed him.

He engineered lots of swindles and frauds

When The Telegraph announced Leonardo DiCaprio signed on to play H.H. Holmes in Martin Scorsese's adaptation of the story (DiCaprio is now slated to executive produce), it described Holmes as "a heroic swindler as well as a mass murderer." That's no exaggeration.

Long before the Murder Castle, Holmes started his dark ways with insurance fraud. While he was a student at the University of Michigan, he would steal bodies from the medical school, mutilate them, and then collect insurance claims. His tuition was paid with money he'd swindled from a wealthy woman, and according to Forensic Scholars Today, that was a regular thing. Holmes wooed and married multiple women, then convinced them to make him the beneficiary of their fortunes before leaving them. He once juggled three women in three different cities at one time.

According to The Telegraph, he also masterminded some bizarre scams, like selling a cure for alcoholism or selling a machine he claimed could turn water into gas. Really, it was a washing machine he'd hooked up to a gas main, but he was such a charismatic liar that his pyramid schemes worked. He even ran one out of the Murder Castle: There was a pharmacy on the first floor from which he sold magical, "miraculous healing mineral water" by the glass.

He ran a legitimate business — briefly

According to a profile published in Harper's Magazine, running cadaver-fueled insurance scams remained a favorite pastime of H.H. Holmes. He made thousands. He also built a pyramid scheme that involved borrowing money to buy a piece of land, borrowing against the land to repay the first loan, then building a house and furnishing it on credit, selling the furnishings to pay for the house, and keeping what was left. He wasn't all tricks, though. He did make one attempt at running a legitimate business.

It was called the A.B.C. Copier Company, and he opened it soon after moving to Chicago. The business was making high-quality copies of various documents, and that was legal enough. He even employed a stenographer. The first employee, he paid. (Those who followed were seduced or killed, whatever he deemed best.) The business failed, and Holmes left his creditors empty-handed when he absconded with 50 gallons of glycerine (which likely became an ingredient in nitroglycerine). That's when he moved to 63rd and Wallace streets, to the building that would become the Murder Castle.

The strange role of Minnie Williams

H.H. Holmes' life wasn't just dark and depraved; it was massively confusing. Trying to sift through the details is like trying to untie the rat king's tail. But there are confirmed bits and pieces. According to Harper's Magazine, Holmes hooked up with Julia Conner in 1890 and moved her and her 8-year-old daughter into the Murder Castle. Then her husband left, and Holmes went off to Texas, where he met Minnie Williams.

Harper's says Williams was a wealthy young woman who fell in love with a man she knew as Harry Gordon. She moved to Chicago with "Harry" in 1893 and quickly grew jealous of Conner, who later disappeared. (The remains of a young child were later found in the basement, thought to be those of Conner's daughter.) Williams became the mistress of Murder Castle, and while no one knows whether she was more victim or accomplice, her sister was invited to join them in Chicago ... and then promptly disappeared. Holmes later said Williams had killed her sister in a jealous rage. While it's hard to take his word for it, she did almost anything for him, including being a witness to one of his many marriages. That marriage was in January 1894; Williams disappeared within a few months.

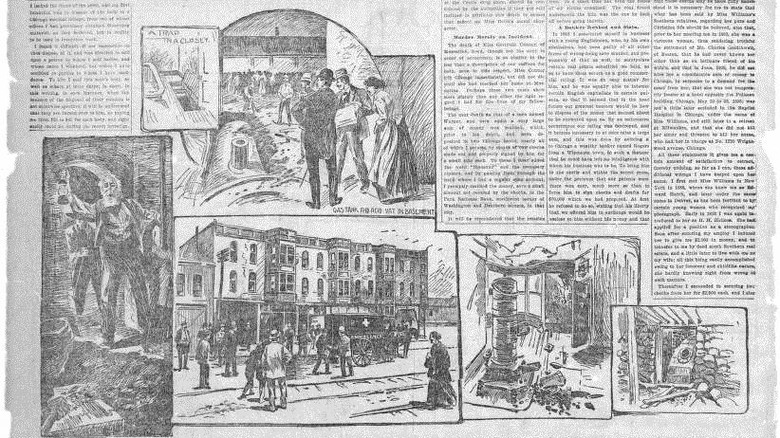

The Murder Castle

The Murder Castle was every bit as insane as you could imagine it. According to Chicagoist, H.H. Holmes built it during the chaos preceding the 1893 World's Fair, and as Chicago prepared to welcome millions, Holmes prepared to welcome them, too.

It started in 1887, when Holmes took over the pharmacy he'd been working at after the owner mysteriously disappeared. Construction of the Murder Castle took about 18 months because Holmes fired worker after worker — in part to keep from paying them, and in part to keep anyone from catching on to the full extent of what they were building. It was finished in 1892 and covered a whole city block. One of the three floors was even open to the public. Holmes rented out areas to merchants and rooms on the upper floors to unsuspecting travelers.

Holmes had an office on the third floor, along with a bank vault and a series of rooms, angled hallways, dead ends, and stairs to nowhere. The second floor had 51 doors leading from six hallways, to 35 normal rooms and plenty of not-normal rooms. Some were airtight, some were soundproofed, and some of the doors led to closet-sized rooms fitted with gas pipes. There were trap doors, sliding panels, and yes, there really were secret chutes that would open and send guests to the basement.

The basement and H.H. Holmes' bizarre beliefs

The idea of stepping into H.H. Holmes' dark, brick-walled basement for the first time is unfathomable, and it's impossible to imagine the horrors law enforcement were confronted with when they finally stepped inside. According to Chicagoist, the centerpiece of the basement torture chamber was something the police described as a medieval rack. Holmes gave it the much more catchy name of "elasticity determinator," and he used it to try to prove the human body could be stretched almost infinitely.

Harper's Magazine says Holmes never completely explained his theories — or how the machines were supposed to work — but that he believed he could eventually create an entirely new race with his experimentation. To those ends, he stretched some of his victims in the hopes of kick-starting his race of giants. Others, he just wanted to get the details on their fortunes.

The basement was also kitted out with several pits filled with quicklime and acids, a crematory, operating tables, and cabinets filled with surgical instruments. Horror movies don't have anything on this because this was very, very real.

Charles Chappell, skeleton articulator

H.H. Holmes didn't dispose of all his victims' bodies in the quicklime pits or crematory. For some, he had the help of a man named Charles Chappell, a so-called "skeleton articulator" whose job was way more disgusting than it sounds. Chappell was in charge of stripping what was left of the flesh off the bones, then reassembling them into a skeleton that could be sold to a medical school or just kept.

It's unclear what happened to Chappell, but Chicagoist says at least one of the skeletons he stripped and prepared belonged to one of Holmes' many assistants, Emeline Cigrand. When she disappeared, Holmes claimed she had run off with a stranger, but later investigators linked her to the skeleton Holmes had sold to a nearby school.

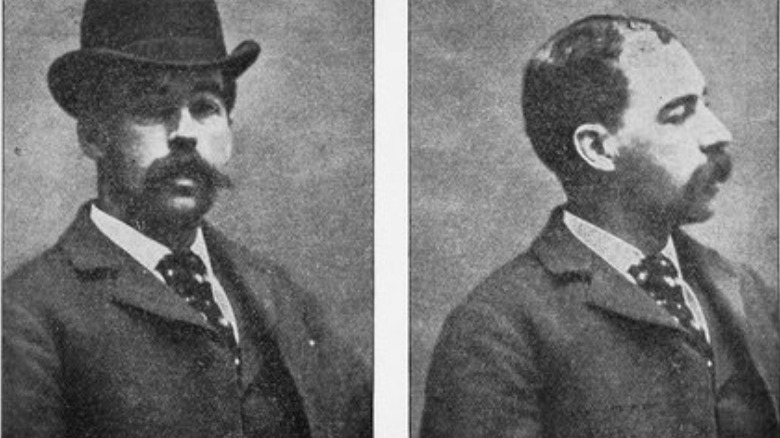

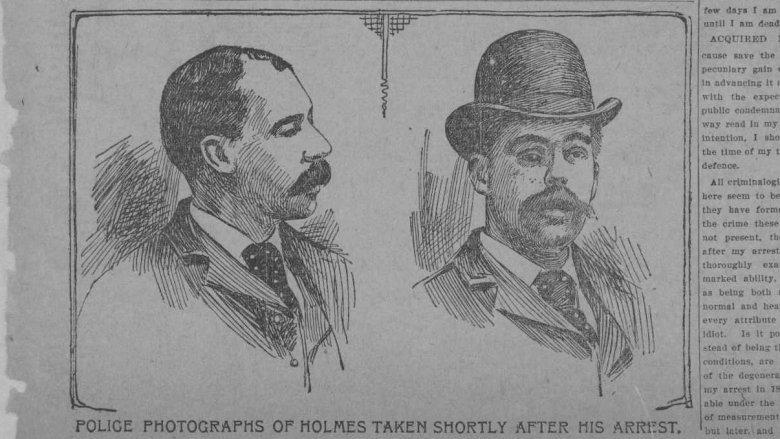

Suspicions were aroused when he murdered his partner

Say what you will about H.H. Holmes, but there's no arguing the fact he was diabolical, charming, and incredibly good at convincing anyone to believe anything. He got away with murder for years, and according to The Philadelphia Inquirer, it wasn't until he made a few crucial mistakes that things started unraveling.

The first was that he killed his partner in 1894, a man named Benjamin Pitezel. He met Pitezel about the same time he met Minnie Williams, and he definitely recruited Pitezel into his schemes. The plan was pretty simple: fake Pitezel's death, then collect and split the insurance money. Instead, Holmes got him drunk, set him on fire, collected the cash, and left town with three of his children. When the claim was investigated as fraud, law enforcement caught up to Holmes in Boston and sent him back to Philadelphia, where he'd killed Pitezel.

Philadelphia assigned one of its best officials, Frank Geyer, to look for the missing kids. When he tugged on that single string, the whole elaborate tapestry started to unravel, beginning with the discovery of two Pitezel daughters — ages 11 and 15 — decomposing beneath a Toronto house Holmes had briefly rented.

The Pinkertons were put on his trail by a train robber

There was another finger pointing at H.H. Holmes, too. Also in 1894, a convicted train robber named Marion Hedgspeth, in jail in St. Louis, came forward to make a statement. A few months earlier, an inmate accused of fraud who went by the name "H.M. Howard" had promised to pay Hedgspeth $500 if he could recommend a lawyer who would be totally fine with helping him commit insurance fraud.

Hedgspeth suggested a lawyer, but Holmes got out on bail and never paid up. Upset, Hedgspeth ratted, and detectives from the Pinkerton agency were sent after Holmes. They tracked him to Philadelphia — where he was in the middle of killing his partner — and from there, the Pinkertons led the charge to arrest him in Boston (via Executed Today).

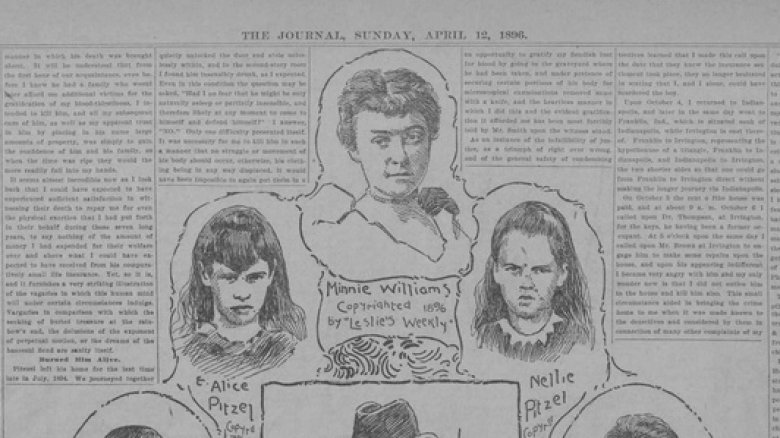

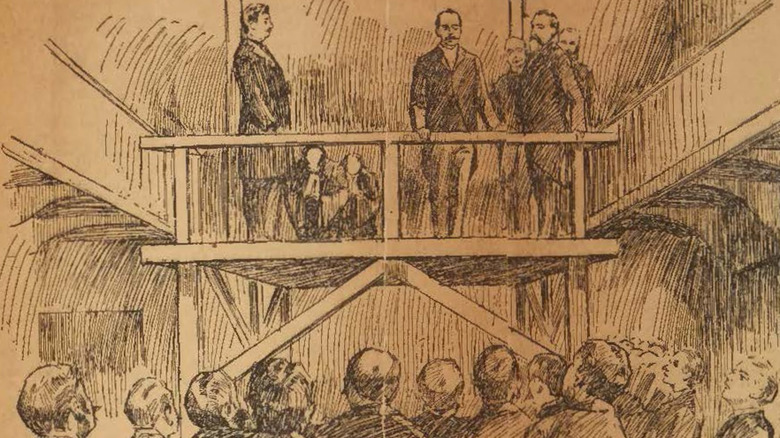

H.H. Holmes denied wrongdoing at his execution

According to Executed Today, H.H. Holmes showed no sympathy when Benjamin Pitezel's wife testified against him at his trial, but when his own current wife took the stand, he played the part with a "fount of emotion." He largely defended himself — with some aid from an attorney — and was given the death penalty on November 2, 1895, less than a week after the trial started. Holmes appealed several times, and when it became clear that he wasn't going to dodge the death penalty, he sold his confession to a newspaper for $7,500. He confessed to 27 murders, then denied any of it was true the day after it was published.

He was hanged on May 7, 1896, and as he stood on the scaffold he gave his last words, saying (in part), "I only wish to say that the extent of my wrongdoing in the taking of human life consists in contriving the killing of two women that have died at my hands as a result of criminal operations." He went on to deny killing Pitezel or his children and was hanged. Afterward, his final wishes were granted: He would be entombed in cement and buried 10 feet underground.

The end of the Murder Castle

If the Murder Castle was still standing, there's no doubt it would have been turned into a tourist attraction. It almost was. According to Chicagoist, the building was bought only a few weeks after the police finished combing it from top to bottom. (That investigation must have given them nightmares for the rest of their lives.) Someone named A.M. Clark planned to open it to the public, but the building caught fire under mysterious circumstances. Explosions were heard only moments after a nearby night watchman saw the fire. An hour and a half later, most of the building had collapsed. A Post Office (pictured above) stands on the site today.