The Turbulent History Of Chechnya And Russia Explained

Russia's invasion of Ukraine has brought Vladimir Putin into the media limelight once again. But appearing alongside him is another figure less-known to American audiences — Chechen president Ramzan Kadyrov, who, according to Emirati news outlet Al Arabiyya, has deployed his forces to Ukraine in support of the Russian army. The cooperation between Russians and Chechens might surprise those who remember the brutal conflicts of the 1990s and early 2000s, when Russia and Chechnya clashed over Chechen independence.

Russians and Chechens are commonly perceived as enemies. After all, the former are Orthodox Christian Slavs, while the latter, per the "Peoples of the USSR" are Nakh Caucasian Muslims with a long history of fiercely resisting Russia. These mountaineers, as Spanish paper AS notes, have lived in their homelands since time immemorial, enduring wars, deportations, and attrition at the hands of Russian invaders. Old grudges die hard, but for now, it appears that Chechnya is happy to work with Putin's Russia for its own interests and shelve historical grievances. How did it come to this? Relationships can change with political and economic winds, and the Russo-Chechen arrangement is no exception. Here is a history of the fraught relationship that has led to the strange year of 2022.

First Blood

According to The Slavonic and East European Review, Ivan IV adopted an expansionist policy bent on conquering the Tatar khanates to Russia's east. The 1556 conquest of the khanate of Astrakhan brought the Tsardom of Russia to the foothills of the Caucasus, a formidable barrier that gave Russia a defensible natural border against its Ottoman rivals.

Soon, Russian forces had the casus belli needed to enter the Caucasus itself. Although the Caucasus was mostly Muslim, there existed a small Christian enclave inhabited by the Ossetian people. According to the report "The Georgia-South Ossetia Conflict," the Orthodox Ossetians voluntarily placed themselves under the rule of their Russian co-religionists in 1774. Russian expansion now worried the Ossetians' Ingush and Chechen neighbors, who opened hostilities with Russia fearing they would soon be attacked.

According to Circassian World, the 18th-century Chechens and Ingush, although Muslim in name, were still heavily pagan in practice. But Islam soon proved a banner of unity in opposition to Orthodox Russia, leading to the rise of Chechen cleric Sheikh Mansur, or Ushurma, (shown above) in 1785. Declaring a holy war against Russia, his early success at Aldyi attracted mountaineers from across the Muslim Caucasus to his cause. His offensive campaigns, however, in cooperation with the Ottoman Turks, failed. He died in Russian captivity in 1791. But Ushurma had inspired something in his people, heralding the start of a relatively-unified Caucasian resistance against Russia.

Colonizing the Caucasus

With Mansur Ushurma's defeat, Russian forces under Czar Alexander I began an earnest conquest of Chechnya and Ingushetia under czarist general Alexei Yermolov (above). According to the Journal of Social Evolution and History, Yermolov saw Chechens — "a bold and dangerous race" — as his biggest problem. After attempts to submit the Chechens bloodlessly resulted in a series of Russian defeats in the Caucasus' narrow valleys, Yermolov decided to barricade the Chechens in their own mountains.

Yermolov used a three-pronged strategy to defeat his opponents. First, as noted in professor Michael Khodorokovsky's study, he adopted a classic divide-and-rule strategy. St. Petersburg tried to co-opt Caucasian elites, enticing them with promises of status and power in return for conversion to Christianity. This strategy worked among the Tatar and Circassian nobility, but not so much in Chechnya and Dagestan. So Russia settled on simple attrition. Russian forces burned towns, villages, and forts to resettle their inhabitants in places where they could be more easily controlled. Resistors, or "scoundrels” as they were called, were ruthlessly eliminated.

Finally, according to professor George Anchabadze (via Circassian World), Yermolov began the construction of a series of fortifications along the Terek and Sunzha Rivers. This line was reinforced with garrisons, and Cossack and Turkic settlers cut off the eastern Chechen lands from the western part in Ingushetia. Local Chechens that surrendered to the Russian garrisons kept their lands while resistors were killed or deported. By 1829, not just Chechens — but Dagestanis, Adyghes, and numerous other Muslim Caucasians — realized that without a leader, there was no stopping the Russian juggernaut.

Imam Shamil and the Caucasian War

According to University of Illinois professor George Anchabadze (via Abkhaz World), the Caucasian conflict, whose beginning some historians date to 1817, continued until 1864. In the late 1820's, the Caucasus came together into a state called the Caucasian Imamate. In 1834, a Caucasian Avar imam from Dagestan named Shamil took charge of it and began to develop it into a theocratic Islamic state.

According to the Journal of Caucasian Studies, the fractious Caucasus needed some common unifying ideology. They turned to Shamil's Muridism, an Islamic movement that replaced Caucasian tribal law with Sharia. Adherence to the new legal code and the collection of religious taxes to fund the war was policed through the Imamate's institutions. This unity brought Shamil success and popularity in the region, as Circassians, Abkhaz, Ubykh, and Chechens all joined his cause (Tolstoy's Hadji Murad was based on this conflict). Russia was now on the defensive.

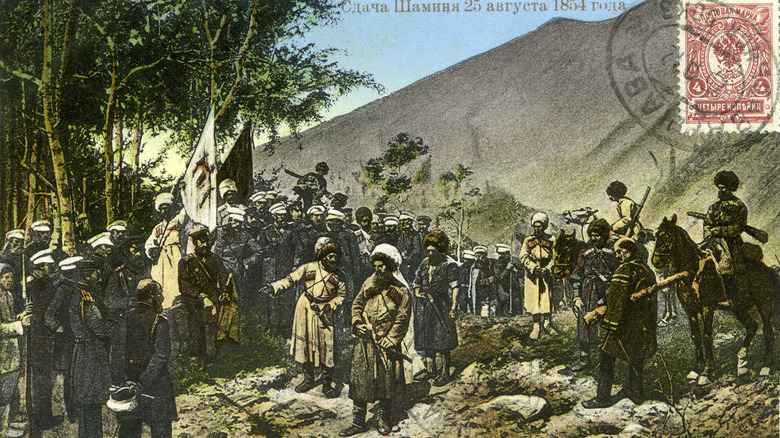

The inevitable Russian counterattack under General Alexander Baryatinsky resumed the hated scorched earth tactics, and Shamil was eventually forced to surrender (as depicted above). The imam, however, was, however, treated with respect (the czar even received him personally). In Europe, he was a celebrity, even having an autographed portrait sent to one of his biggest fans — Queen Victoria (via the Royal Trust Collection). But Russia was now in control of his Caucasian homeland, which would now suffer ethnic cleansing.

The expulsions of 1864-'65

The fierce resistance to Russian rule convinced Czar Alexander II that the Muslim Caucasians that refused to submit had to be removed somewhere far away from their homes where they could be more easily policed — or expelled from Russia entirely. According to professor George Anchabadze (via Abkhaz World), Russia offered their Circassian enemies settlement on the Russian steppe. But few took the offer, leading to a fresh war that saw Circassia devastated.

Here, the gloves came off. According to researcher Steven Shenfield (via Circassian World), the Russian government opted to expel the large portions of Caucasian Muslims into the Ottoman Empire, including over 90% of the Circassian population, virtually all Ubykhs, and Abkhazian Muslims (Christians were allowed to stay). The Ottoman Empire offered to take them, but many perished from disease or drowning on the voyage to Anatolia. As Al-Jazeera notes, this is a major sore spot among Muslim Caucasians today, who have demanded Russia recognize the events as genocide.

While the expulsions mainly affected the coastal regions, Chechnya was dealt a similar fate. According to the Encyclopedia of European Peoples, 40,000 Chechens fled or were expelled into the Ottoman Empire in 1865. An 1893 discovery of oil accelerated Russian colonization, making the unthinkable prospect that they would not survive as a people a grim possibility.

The Russian Revolution

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, made possible with German complicity, led to the breakup of the Russian Empire and its replacement with the USSR. By this point, as Abkhaz academic Stanislav Lakoba noted (via Abkhaz World), the Caucasians had absorbed the lessons of the 19th century well. Unity was the key to freedom and independence. So in 1917, the Caucasus Mountain Peoples' Republic, which united Abkhaz, Chechens, Circassians, Ingush, and others under one flag, was born. The republic was given a fighting chance in 1918 when Germany and the Ottoman Empire recognized its independence.

When World War I ended, however, the Caucasian independence movement lost support, as both Germany and the Ottomanb Empire were dismembered to form the Weimar and Turkish republics, respectively. The new republic was on its own, and the nationalists were soon replaced with Muslim theocrats that sought the continuation of Shamil's 19th-century imamate. In 1919, according to "Creating New States," they succeeded, renaming the republic the "North Caucasian Emirate."

The new state did not survive. Already weakened by communist uprisings within its own borders, the Red Army swept in and annexed it. Fighting continued into 1925, but Chechnya would not break free of Soviet rule until the federation collapsed in 1991.

Chechnya under the Soviets

According to France's Sciences-Politiques, Joseph Stalin's USSR set about redrawing the boundaries of the Caucasus. Chechnya and Ingushetia were merged into a single SSR and Sovietization, and collectivization — the attempt to merge small landholdings into larger state-run enterprises — began. But Caucasians vastly outnumbered Russians and lived outside cities in hard-to-reach mountain valleys where Soviet influence was nonexistent. Thus, traditional Chechen kin loyalties and the Muslim religious establishment survived as a base for future resistance.

In 1943, a handful of Chechen separatists reached out to Germany in hopes of aid against the Red Army, so the Soviet government accused the entire Chechen nation of conspiring against the USSR and ordered them removed from their lands. Under the NKVD's (the Soviet secret police) ruthless Lavrenti Beria, Chechens and Ingush were lured from their villages, rounded up, and deported to Central Asia in the Aardakh Expulsions, which fulfilled the definition of genocide. Nearly a quarter died along the way.

Although it was the USSR that was responsible for the deportations instead of Russia, the USSR had reinvented itself as a Russian state, making the two synonymous as far as Chechens were concerned. Per Russia Beyond, in order to inspire resistance against the German invasion, Stalin had rehabilitated Russian nationalism and legalized the Orthodox Church. After deporting the Chechens, Stalin colonized Chechnya with Russians and other non-Caucasians, while Chechnya's cities were rebuilt in Soviet fashion to hide any mention of their old inhabitants. Although allowed to return home in 1957, Chechens never forgot, making the deportations a central part of their 1991 independence bid.

The First Chechen War

Chechnya endured 34 more years of Soviet rule until 1991, when the USSR collapsed. The end of the Soviet Union gave its constituent republics independence, and Chechnya was eager to join them. According to Stanford's Center for International Security and Cooperation, Dzhokhar Dudayev declared the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria that year. But unlike previous Chechen attempts at statehood, he jettisoned Islamic agendas in favor of a secular, nationalist one.

According to the National Interest, the republic announced its appearance on the international scene by defenestrating local communist party bosses. An uneasy peace endured between Russia and Chechnya, but under the table, Boris Yeltsin's government was financing Dudayev's opponents. In December of 1994, Russian forces invaded Chechnya.

On paper, Russia should have crushed the Chechens. But the Russian army was a shadow of the Soviet Red Army, suffering from low morale, understrengthened and under-equipped units, and unwilling soldiers. The Chechens, on the other hand, were (for now) united under a common purpose. In the bloody fighting that followed, first in the capital Grozny and then throughout the countryside, Chechen militias drove the Russians from the republic. A humiliated Russia lost 8,000 soldiers and de facto recognized Chechen independence with the Khasavyurt Accords. Now Chechnya had to overcome internal divisions to build a unified country.

Chechnya degenerates

Once Chechnya was independent, Dzhokhar Dudayev's government faced the monumental task of rebuilding the country. According to the University of Glasgow, Chechnya in 1996 was economically ruined and lacked any international recognition. Tribal loyalties resurfaced as different Chechen factions and families accused each other of Russian collaborationism or simply not doing enough for the independence cause. Outside of the capital Grozny, Dudayev's government had virtually no authority.

Into the vacuum stepped Saudi Wahhabism. According to the journal Europe-Asia Studies, this austere, fundamentalist brand of Islam entered Chechnya during the '94 war alongside Mujahideen veterans of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Chechnya's warlords, the most important being Shamil Basayev, saw opportunity in the ideology. It allowed them to tap international jihadist networks financed from the Middle East, yielding millions in funding and hundreds of foreign fighters. The cash flow in turn strengthened the warlords and religious establishment's leverage on the weak Chechen government in Grozny, even though the Wahhabis were quite unpopular among the Chechen public.

With Wahhabism's spread, Chechnya soon became co-opted into the international Islamist struggle. No longer was the Chechnya war an isolated conflict — it was part of the defense of global Islam against Russian infidels.

The Second Chechen War

The Second Chechen War was a bit of a mess — to put it mildly. According to Europe-Asia Studies, President Aslan Maskhadov (pictured above) caved to Islamist demands for a new constitution that made Islamic Sharia the basis for Chechen law. Bors Yeltsin's Russia, meanwhile, concerned that Islamist warlords and militants were becoming too bold, began air-striking them. Yeltsin had hoped that weakening the warlords would strengthen Maskhadov, but it did the opposite. Chechens viewed their president as a Russian puppet.

Shamil Basayev meanwhile, flush with Middle Eastern cash, responded by attacking Russian soldiers in Dagestan. Maskhadov was powerless to stop him but tried to placate Russia by offering to arrest and hand over the responsible jihadists. But he was no longer dealing with Boris Yeltsin. He now faced an iron-willed Vladimir Putin, who ordered a full-scale invasion of Chechnya to smash the insurgency and the separatists once and for all.

Russia's attitude can be summed up with the following maxim: "We do not negotiate with terrorists." With this attitude, the Chechen conflict became a fight against international jihadism and terrorism — or as journalist Steven Hawkes noted, a "War on Terror." According to Radio Free Europe, the swift Russian response brought Chechnya back into Russia, with enormous cost for the locals. Grozny was levelled again and upwards of 80,000 civilians lost their lives.

The Beslan School Siege

The remaining Chechen insurgents turned to terrorism. Militants and the infamous female "Black Widow" suicide bombers (via Eurasia News) attacked Russian targets with few scruples. The campaign came to a tragic climax in 2004, when, according to Time Magazine, a group of Chechen-Ingush (and, reportedly, Arab) militants seized a Beslan school and its students, teachers, and parents in the mainly-Christian Republic of North Ossetia-Alania and took them hostage.

Russia first attempted to negotiate. Hoping to save the children from thirst and malnutrition, some adults offered themselves in their place. Russian forces held their fire even when fired upon, and in a last-ditch attempt, offered the terrorists safe passage in return for the hostages' release. The insurgents eschewed negotiation, as did Russia when Aslan Maskhadov offered to mediate. Per the BBC, Russia would hold Maskhadov responsible for the siege and kill him in 2005. Former Ingush president and Vladimir Putin critic Ruslan Aushev, however, managed to secure the release of 26 infants and their mothers.

The hostage crisis escalated after explosives the militants had placed in the school killed two Russian soldiers retrieving dead bodies. Russian special forces decided to storm the school. The consequences were nothing short of horrific. By the end, 330 people (mostly children) were dead. Interethnic relations in the Caucasus took a nosedive as Christian Ossetians seeked retribution against their Ingush neighbors; the incident tainted Chechnya, reinforcing stereotypes of implacable Chechen jihadists at war against Orthodox Russia. Chechens and Russian opposition, however, blamed Putin for the deaths, accusing him of eschewing negotiation to create a tragedy for political gain.

Kadyrov and contemporary Chechnya

According to Radio Free Europe, the string of Caucasian Islamist attacks throughout Russia, of which Beslan was just one, allowed Vladimir Putin to ram through a controversial bill that allowed him to appoint regional governors and override local elections. The law was marketed as a counterterrorism bill that gave the Russian president control of the legislatures of the Caucasus. If a local legislature appointed a separatist governor, Putin could legally veto the appointment and dissolve the dissenting legislature.

The biggest beneficiary of the law has been Chechen president Ramzan Kadyrov, a controversial figure to say the least. Per RFERL, western governments and humanitarian groups have accused him of murder, kidnapping, torture, public humiliation, and a host of other human rights abuses. His supporters, per the BBC, tout his rebuilding of the war-ravaged capital of Grozny into a modern city — all while annihilating Islamist insurgents.

Kadyrov's strategy markedly differs from those of his predecessors, walking the line between devout Muslim on one hand and pro-Russian Chechen nationalist (a seeming contradiction) on the other. As the London School of Economics notes, Kadyrov has attracted investment from wealthy Gulf Arab states and acts as Putin's go-between when dealing with Muslim countries. Per the BBC, he has also stamped out jihadists in return for Russian non-interference and restored Chechnya's damaged reputation — all while enforcing Islamic morality at home. He has not wavered in the Ukraine conflict, per Novinite, faithfully deploying Chechen soldiers and demanding Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky surrender and apologize to Putin for his behavior.

Going forward

Today, relations between Russians and Muslim Caucasians are at times fraught, depending on the place. As Open Democracy notes, Russia proper, especially the Stavropol region, have experienced increased Caucasian migration. Stavropol has a special place in Russia historiography as Russia's front line in the Caucasus courtesy of its border with Chechnya. Chechen warlord Shamil Basayev knew this and laid siege to a Stavropol hospital in 1995 during the First Chechen War.

Migration has brought ethnic tension to Stavropol, the result of economic and demographic factors. Caucasian immigrants and local Russians compete for jobs, particularly in lower-wage sectors, while local Russians have no interest in seeing their demographic majority eroded by Muslim Caucasians. In 2007, ethnic riots left two Russians and one Chechen dead, while interethnic violence has become regular outside the city.

Stavropol's sentiments are found in other parts of Russia, to the point that in 2011, 20% of Russians wanted to expel the North Caucasus from the Russian Federation to prevent any more from migrating. But with Ramzan Kadyrov at the helm of Chechnya, this is unlikely, at least for now. Chechen-Russian relations find themselves in new territory, while the small republic, per the BBC, is firmly in Russia's orbit. Russian success or failure in Ukraine may make or break these ties, but that remains to be seen.