Hobbies From The Victorian Era That Seem Bizarre Today

Victorians didn't play around when it came to the importance of diversion, according to Hugh Cunningham's "Leisure in the Industrial Revolution: c. 1780- c.1880." Pastimes blossomed among members of the middle and upper classes. H. A. Bruce acted as one of the biggest advocates for leisure time, giving regular speeches on the subject. In 1855, he argued, "Next to the deep-pervading sentiment of religion, I know nothing of more importance to the well-being of a people than well-ordered amusements."

But hard labor also proved foundational to the era's notions of improvement and progress, per Hartford Stage. After all, the Industrial Revolution remained in full swing, and Great Britain dominated the globe through extensive trade networks, a powerful navy, empire-building activities, and manufacturing (via Britannica). To maintain this dominance, the lower classes covered the jobs no one else wanted while the middle and upper classes dabbled in less mundane pursuits.

Members of the Victorian middle-class even hoped that pastimes might act as a unifying balm of "class conciliation." (For the middle and upper classes, that is.) Despite these ambitious hopes, many leisure activities chosen by Victorians look downright bizarre from our modern perspective. They explored everything from anthropomorphic taxidermy to seaweed scrapbooking, human-hair jewelry to freak shows, and even post-mortem photography. Here are some of the strangest free-time activities of the 19th century.

'Anthropomorphic taxidermy'

Taxidermy is usually the purview of museums and hunters today. But during Victorian times, many people collected anthropomorphized stuffed animals arranged in whimsical tableaux (via Atlas Obscura). These pieces represented the perfect mix of two interests espoused by Victorians: the love of natural history and whimsical fantasy. For example, Victorians collected scenes such as weddings attended by kittens, playgrounds full of frogs, and ice-skating hedgehogs.

As strange as these deceased dioramas look, they required a serious amount of skill and hours of meticulous work. No artist of anthropomorphic taxidermy better personified the possibilities inherent in the craft than the German taxidermist Hermann Ploucquet. He worked for the Royal Museum in Stuttgart, expertly combining his artistic talents with a love of science. Ploucquet enjoyed widespread commercial success, "dazzling" everyone from Charlotte Bronte to the two Victorian "Charles" — Darwin and Dickens. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert doted over Ploucquet's work, and the queen later wrote in her diary that it was "really marvelous."

Another noted taxidermist, Ferenc Mere of Hungary, devoted 10 years of his life to catching, killing, and stuffing frogs, as reported by National Public Radio (NPR). After skillfully preserving them, he posed them like humans and dressed them in clothes, recreating countless scenes from daily life. Mere's work can still be viewed at Froggyland in Split, Croatia.

Pteridomania

Humanized stuffed animals weren't the be-all and end-all for Victorian hobbyists. Other bizarre pastimes abounded, including pteridomania or "fern fever" (via Atlas Obscura). According to Plant Explorers, the pursuit took root in 1829 when the famous British botanist Nathanial Bagshaw Ward saved a moth pupa in a sealed glass jar. Realizing he was onto something, he started growing emerald-hued foliage in glass cases, too.

Soon, the pursuit caught on among other science-minded Victorians. To commemorate Ward, people referred to these glass containers as Wardian cases. But today, we know them as terrariums, per Tovah Martin's "The New Terrarium: Creating Beautiful Displays for Plants and Nature." Think of terrariums as "tiny biospheres," preserving high levels of humidity, the ideal atmosphere for various species of ferns.

Herald Net argues that the concept behind terrariums sprung from necessity. Ward had attempted numerous times to grow ferns while living in London, but the smoke and pollution of the city killed his precious plants. Fortunately, glassed-in enclosures brought success. As more Victorians joined him in "fern fever," the variety of plants expanded, as did the scale of the containers. Soon, terrariums encompassed whole rooms. Gardeners became increasingly experimental, opting for exotic specimens such as rubber and tea plants. To preserve the plants during their journey overseas to Great Britain, they even traveled the ocean in Wardian cases, underscoring how effective Ward's invention proved.

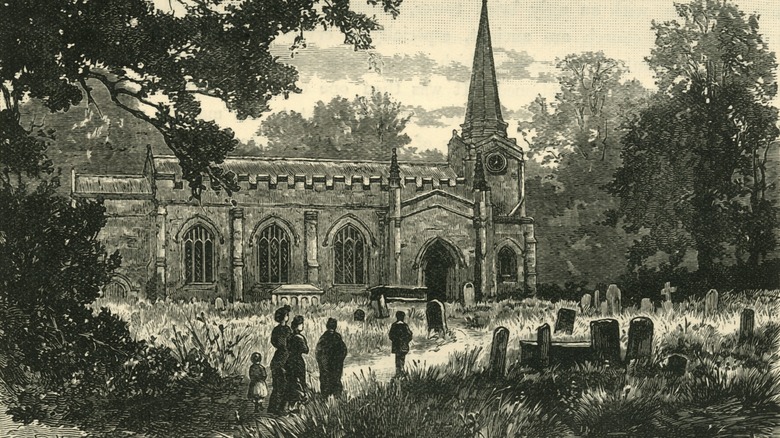

Picnicking in cemeteries

During Victorian times, cemeteries represented the closest thing many people had to public parks, according to The Atlantic. In the days before city planning placed a premium on accessible green spaces, final resting places often fit the bill with their sprawling lawns and beautiful landscaping. The Guardian notes, "From Pagans holding silent dinners to Victorians dining alfresco among the gravestones, England's food traditions have long been shaped by death." These traditions also prevailed in Britain's former colony, the United States.

At the high point of the cemetery picnic movement, visitors flocked to the most popular and picturesque cemeteries, from the Midlands to Yorkshire. Stateside, New York's Green-Wood Cemetery attracted half a million visitors per year by the mid-19th century. These numbers made it the second most popular destination in the state after Niagara Falls.

According to Atlas Obscura, another favorite spot during the 19th century was Woodland Cemetery in Dayton, Ohio. Historic images from the period show large crowds of well-dressed men and women with parasols touring the grounds. If all of this sounds a little morbid, we get it. But it's important to remember that Victorians viewed death differently than we do today. It remained an ever-present reality due to widespread disease, from cholera to dysentery and yellow fever. Dying in childhood or childbirth also proved far too common, leaving no family untouched. So, regular trips to the cemetery were a matter of course.

Making jewelry from human hair

After the tragic death of Prince Albert in 1861, his wife Queen Victoria never remarried, as reported by National Geographic. The couple had enjoyed a legendary love story, and so it's no surprise she found it impossible to move on. She often wore a necklace containing some of Albert's beloved locks, setting the tone for the age.

Atlas Obscura notes that human hair work wasn't invented in the 19th century. It has a much older story. But in Victorian times, people took this art form to new heights, crafting locks of hair into intricate accessories. These included everything from earrings to bracelets to brooches. Unlike the locket that Victoria wore, however, Victorian hair jewelry got downright intricate. The trend began in Europe before making the leap across the Atlantic during the American Civil War when hundreds of thousands of families mourned lost loved ones.

But not all of the locks used in hair art came from deceased individuals. According to Smithsonian Magazine, friends exchanged locks of hair that they added to their albums and autograph books. And wives transformed their tresses into practical pieces like watch fobs their husbands wore to work: "At a time of rising commercialism, sentimental hairwork became a way both to signal one's sincerity and, paradoxically, to stay in style." A handful of organizations specialize in preserving hair artwork today, and as recently as 2020, the Morbid Anatomy Museum offered classes in hair jewelry-making.

Microscopic kaleidoscopes

Eagle-eyed Victorians with a scientific bent also enjoyed crafting single-celled algae, known as diatoms, into elaborate designs, according to Smithsonian Magazine. If you're wondering how they arranged these marvels, invisible to the naked eye, you're not alone. Klaus Kemp, one of the world's last diatom artisans, has practical insights into how Victorians created their designs based on years of obsessive hobbying (via National Geographic).

The specialty of professional microscopists, these artists cleaned the diatoms they collected and then placed them on a glass slide covered with adhesive. From there, the diatomist worked the single-celled life forms into desired patterns, only constrained by how long it took the bond to dry. In the case of Kemp, he uses a special glue that takes days to set, permitting him extra time to arrange his pieces.

As weird as this pastime sounds in the 21st century, it suited many Victorians to a tee. After all, they had a deep-seated curiosity about the natural world coupled with a strong sense of regularity, harmony, and order. Arranging diatoms into fantastic patterns allowed these individuals to explore nature on their terms, expressing it in an orderly and rational fashion while indulging in play and experimenting with microscopes. Kemp sums up this Victorian obsession succinctly, "I find the best arrangements overwhelming. The variety and intricacy of shapes, patterns, and repetitions evoke a profound sense of awe" (via Smithsonian Magazine).

Crystal gazing

Humans have sought to know and control their futures since ancient times. From the prophets at Nebuchadnezzar's court to the Oracle at Delphi, gaining valuable insights about what's to come has long fascinated people. Over the millennia, aspects of the occult persisted in European culture, including mirror or crystal gazing, palmistry, tarot cards, and astrology, according to Alex Owen's "The Darkened Room: Women, Power, and Spiritualism in Late Victorian England."

Victorians relished doing things with gusto, and this proved no less true regarding the art of crystal gazing, as reported by Britannica. This entertainment experience involved "elaborate rituals" for everything from conducting sessions to cleaning the ball afterward. Rules also surrounded the best time to practice the medium — when the sun was at its "northernmost declination." Nineteenth-century adherents of fortune-telling via crystal orbs also came up with detailed histories surrounding the practice, according to the Victorian Web. In some people's minds, these anecdotes may have bolstered the validity of the practice.

For example, rumors swirled about the origins of a crystal ball owned by the Countess of Blessington, claiming it originally came from an Egyptian soothsayer. Some proponents of crystal balls also argued that ancient biblical prophets such as Ezekiel and Daniel relied on crystals to see into the future (via Logle Barrow's "Independent Spirits: Spiritualism and English Plebeians, 1850-1910"). Of course, primary sources don't back up these claims. Nevertheless, these teachings appealed to a "Christian" society paradoxically fascinated with spiritualism and the occult.

Coded flower messages

Victorians cultivated a deep love of flowers, but their enthusiasm went beyond simple admiration, as reported by Atlas Obscura. They developed an intricate signaling code through flowers to communicate everything from chivalry to unrequited love and even potential danger. Think of poesies as the Victorian equivalent of 21st-century emojis.

When a bouquet arrived in the 19th century, people grabbed their flower arranging dictionaries for a little decoding fun. Flower meanings could prove quite intricate, and they weren't always pleasant or sweet. For example, an arrangement of oleanders communicated a warning of swift vengeance to follow. And groupings of hydrangeas, oleanders, delphiniums, and basil came with nasty passive-aggressive messages about the receiver's heartlessness, arrogance, and disagreeability. (Talk about a bad breakup!)

Of course, the language of flowers (a.k.a. floriography) wasn't all bad. Some arrangements conveyed positive or even passionate statements. For example, white heather, hollyhocks, and lupins congratulated the receiver as witty and ambitious while bestowing good fortune. To understand the meaning of such gifts, Victorians cultivated the ability to recognize flower species on sight, pouring over the reference books used for deciphering. That said, some flowers came with enigmatic meanings potentially interpreted in multiple ways, according to the dictionaries of the day. Consider it the 19th century equivalent of "plausible deniability."

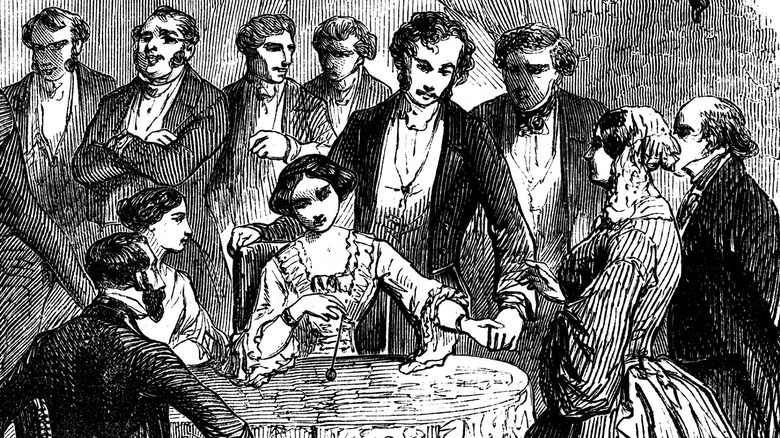

Seances

While Queen Victoria reigned over Great Britain, spiritualism dominated many peoples' religious beliefs, per the New Yorker. Key to this belief system were séances, where guests focused on communicating with the dead. As spiritualism gained popularity during the 19th century, some historians believe upwards of 11 million people identified as spiritualists. And just about every famous person attended at least one ghostly gathering, from Frederick Douglass to Queen Victoria to Mark Twain.

The Guardian notes that the movement proved rife with hucksters. Its founders, Margaret Fox, 14, and her sister Kate (Catherine), 11, of Rochester, New York, claimed they spoke to the dead through tapping. They soon attracted celebs like James Fenimore Cooper, William Lloyd Garrison, and Horace Greeley to their supernatural circles. That said, the sisters eventually admitted they made the whole thing up.

But this didn't deter the most loyal members of the spiritualist movement from proselytizing their new faith. Celebs like the author of the Sherlock Holmes mysteries, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, remained whole-heartedly convinced that communicating with ghosts was not only possible but an important aspect of the human condition. Some adherents even touted the belief system as the "scientific religion," according to Michelle Stacey's "The Fasting Girl." What started in New York as the so-called "Rochester rappings" found their equivalent in Great Britain as people enthusiastically reached out to the dead (via Logle Barrow's "Independent Spirits: Spiritualism and English Plebeians, 1850-1910").

Seaweed scrapbooks

When Victorians weren't busy contacting the dead or arranging single-cell organisms into artwork, they created seaweed scrapbooks (via The Public Domain Review). They collected specimens from the beach and pasted them onto sheets of construction paper, creating elaborate designs or even spelling out words. Some scrapbookers framed the green marine stuff with doilies or lace.

Despite the bizarre materials used to craft these keepsakes, some compositions looked surprisingly elegant. The fantastical esthetic of these works underscore the fact that "the Victorian period had a particular flourish for domesticating the wildness out of nature," as argued by Atlas Obscura. Seaweed albums represented a trendy extension of the very popular art of pressing and saving wildflowers between the pages of books.

As the hobby grew in popularity, just about everyone got involved. Even Queen Victoria, as a young girl, reportedly kept a seaweed scrapbook, per Thad Logan's "The Victorian Parlour." Soon, books supported this diversion, including A. B. Harvey's "Sea Mosses: A Collector's Guide and an Introduction to the Study of Marine Algae." And scrapbooker Eliza A. Jordson wrote a detailed essay on how to properly preserve what Victorians considered an "ocean flower," per the University of Victoria.

Playing amateur scientists

Victorians collected various materials from the natural world, indulging in amateur scientific pursuits, as reported by North Carolina State University's library archives. Their activities involved everything from nature sketches to collecting fossils, stones, birds' eggs, butterflies, beetles, and more. In other words, visiting a trend-setting Victorian home could look like a hot mess of natural wonders most parents would never let their kids bring in the house today.

Science remained an ever-present fascination as grand developments in the field happened at a breakneck speed, instilling in Victorians an insatiable thirst for natural history. Not only was this reflected in their interior décor, but it also shaped popular literature and media. Natural history sections ran in the dailies, where readers could load up on debates about how long frozen toads could live or whether certain types of birds hibernated or migrated.

A growing number of women became enamored with the natural world during this period (via Women You Should Know), including Beatrix Potter. Although she gained fame for her stories about Peter Rabbit, Potter's natural history illustrations prove impressive. No subject proved too humble for her to immortalize in ink and watercolor, including lizards, mushrooms, bats, and rabbits. She even de-fleshed dead animals by boiling them to preserve their skeletons for anatomical study. And the Natural History Museum has declared Mary Anning "the unsung hero of fossil discovery" for her early paleontological work along the English coast.

Postmortem photography

The internet contains plenty of hype about the bizarre Victorian fascination with postmortem photography, as reported by Atlas Obscura. Like other macabre aspects of Victorian culture, photographing the dead was firmly rooted in the fact that mortality stalked Victorian families wherever they went.

Without basic sanitation, an understanding of bacteria and viruses, and modern medical advances, people fell victim to many ailments considered minor today. What's more, death proved an equal opportunist, targeting the young and the old, the poor and the rich (via the National Archives). Even Prince Albert fell victim to an early death. The Prince Consort's passing ushered in 40 years of mourning on Queen Victoria's part, rendering Victorian culture inextricable from extended and elaborate displays of mourning (via National Geographic).

Victorians also had a strange fascination with "memento mori" trinkets. These items reminded the casual observer that nobody could escape the ravages of mortality. With the advent of photography, no better "memento mori" existed than post-mortem portraiture, per the Conversation. Whole families might pose with a deceased loved one, and photographers went to great lengths, in many cases, to make corpses look lifelike. What's more, widespread diseases like tuberculosis, which gave the incurable pale complexions with stunning red lips and cheeks, meant some of the most "beautiful" pictures captured of family members existed alongside death, according to the BBC.

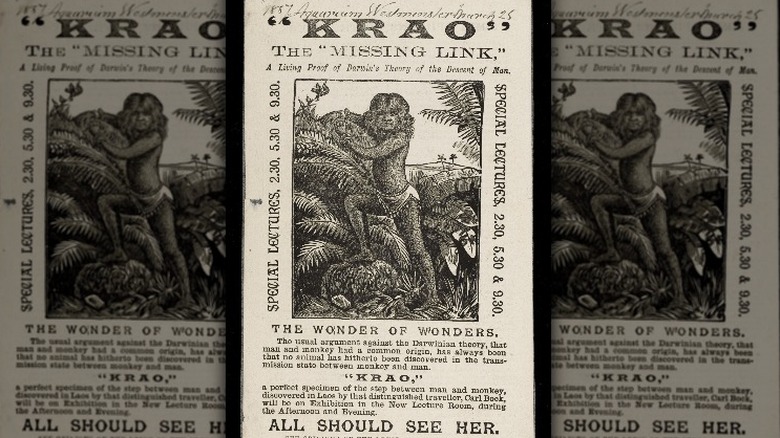

Exploiting human oddities

Weekend entertainment for many Victorians came with a visit to the "freak show," as reported by History Today. Spectators flocked to see bearded women, conjoined twins, and people with various medical conditions. Perhaps the most well-known among them was Joseph Merrick, the so-called "Elephant Man." But he was far from alone. For example, Krao, a young girl from Siam, with hypertrichosis (excessive hair growth, per Healthline) went on display in the 1880s as the "Missing Link."

People flocked to these events, transforming the people they came to see into unenviable celebrities. As Greta the Lobster Girl, a modern woman with ectrodactyly ("lobster claw syndrome") notes, "Up until the 1940s and especially during its Victorian heyday, the sideshow — or 'freak show' — was one of the only sources of gainful employment available to people like me who had unusual or extreme physical or cognitive disabilities" (via The Strike Wave). That said, income came at the expense of their humanity as they faced public ridicule every time they went on display.

The pastime proved so popular that Punch Magazine declared it "deformito-mania," defined as "the prevailing taste for deformity" (via History Today). Victorians coined the term "freak" in the 1840s, short for the phrase "freak of nature." Like all things Victorian, these displays eventually became entangled with science as amateur natural philosophers attempted to understand the conditions people in these shows faced. Some physicians also explored how best to help those like Merrick.