The Most Likely Ways To Die In Victorian England

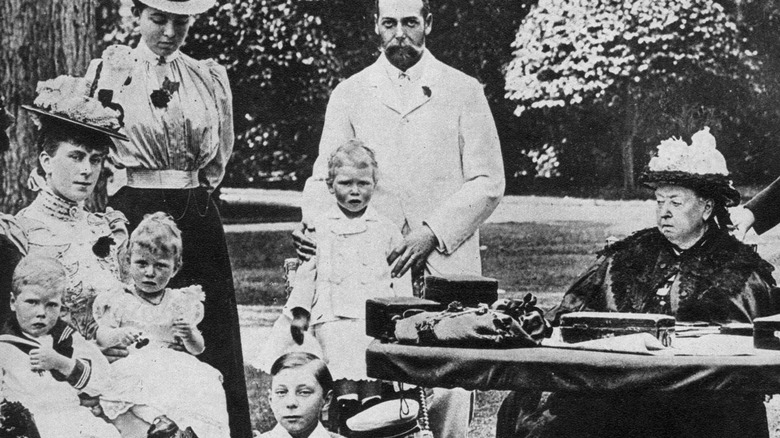

The Victorian Era is so named for the reign of England's Queen Victoria, who ruled from 1837 until her death in early 1901 (via Britannica). It marked a time in the United Kingdom, and in Great Britain itself specifically, of significant change, including rapid industrialization; growing wealth thanks both to this progress and riches gleaned from colonial possessions; advances in science, the arts, and medicine; and explosive population growth — according to Victorian Studies, between the early 1840s and the dawning of the 20th century, the population of England more than doubled. But don't let any of those points fool you: Death was a part of everyday life in Victorian England.

In fact, so accustomed to death were Brits of the era that it was normalized in a way hard to fathom at present. According to History, it was entirely common for family members of the deceased to dress and prop up corpses for one last photo op, for burial ceremonies and gravesites to become ever more elaborate (and expensive), and for the mourning process to take on an air akin to pageantry.

All of which is unsurprising when you appreciate how close a hand death could be for Victorians. Here are some of the most common ways death came.

Stillbirth

The leading cause of death in the Victorian Era, according to the University of Leeds, was being born in the first place. Instances of stillbirths were so common that simply being born was the biggest killer of the times. The causes of stillbirths were many, including poor maternal nutrition, inferior birthing facilities and personnel, and many easily communicated diseases and infections inflicted while the fetus remained in utero, to name a few. Untrained midwives were also a problem that contributed to the high stillbirth rate; as an article in Archives of Disease in Childhood points out, there were no rules about midwife education in England until 1902, the year after Queen Victoria died.

An article in The Journal of Anatomy explains that poor women would sometimes be so desperate for money that they would sell the bodies of their stillborn infants to medical schools, and skeletons of fetuses and infants from this period remained in the collection of, among other places, the Univerity of Cambridge even in the 21st century.

Nor did the end of the Victorian era mean this problem improved: From 1917-1927, a stunning and saddening 4.3% of all births in Leeds were stillbirths, so more than one in 25 births saw a baby born already having died.

Consumption

Today, people have a perfectly good understanding of the disease tuberculosis, often called simply TB. It is a highly infections illness caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and it primarily afflicts the lungs but can have severe deleterious effects on other parts of the body as well, including causing fevers, nausea, aches and pains, seizures, extreme fatigue and confusion, and, of course, death (via Healthline). Except that today, in almost all cases, TB is easy to treat when it even crops up at all, according to the WHO.

In Victorian England, TB was not quite so well understood. At all. Then referred to as "consumption" for the wasting effects the sickness had on the afflicted — seeming to cause a person's body to veritably consume itself from within — tuberculosis was usually a death sentence to those who caught it (via Thorax). In fact, in the early decades of the 1800s, as many as one in four deaths in the U.K. were caused by TB. By the 1900s, however, with understanding of and treatments for the disease both vastly improved, instances of consumption/TB leading to death fell year after year. In the modern era, about 350 Britons die from TB each year, according to NHS, a figure representing a fraction of Victorian Era TB mortality.

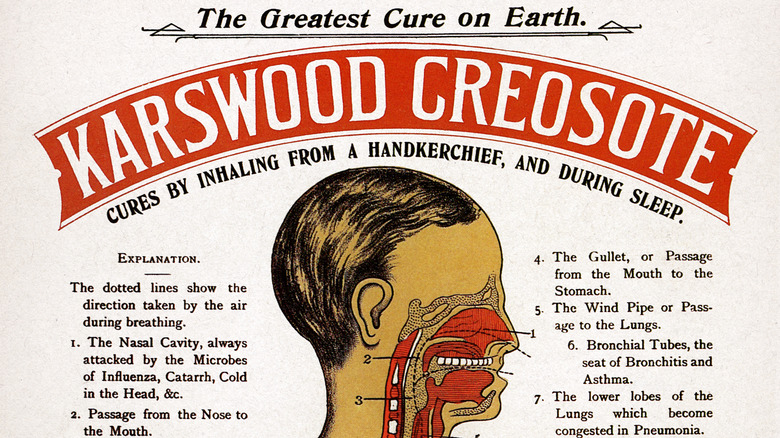

Bronchitis

According to the Mayo Clinic, "Bronchitis is an inflammation of the lining of your bronchial tubes, which carry air to and from your lungs." The condition usually develops following a respiratory infection like a cold or flu (or a coronavirus infection) and, in most modern cases, is easily remedied with medical attention if it doesn't just ameliorate on its own. In the Victorian Era, however, it was a different story. Back then, bronchitis was responsible for as many as 8% of deaths in the U.K. (via the Journal of the COPD Foundation).

While the overall (and grim) statistics are clear — that bronchitis was a killer, and a bad one at that — what's not clear is how often the issue was acute bronchitis or chronic bronchitis. Acute bronchitis was often due to another infection and lead rapidly to complications and death. Chronic bronchitis, however, could slowly weaken a person for months or even years and was exacerbated by things like smoke and pollution, ever more present problems in the industrializing England of the times. Either way, it was an unpleasant way to die, with the sick person slowly suffocating within their own body, while suffering fever, cough, chills, aches, and other symptoms that could worsen steadily.

Convulsions

In Victorian England, so-called "convulsions" were a leading cause of deaths for infants — "so-called" because frankly doctors of the day called all sorts of things convulsions when they really had no idea what to properly call the underlying symptoms or sickness. Though according to the University of Leeds Library it was understood as early as the late 18th century that the seizing and spasms often termed as convulsions could be caused by myriad factors, the cause of death given for babies in the 19th century was simply listed as "convulsions" in many cases.

The seizing and spasms was often accompanied by fevers, chills, pains, coughing, and many other symptoms that to a modern medical practitioner may have revealed the real causes of affliction. But according to journal Child's Nervous System, it was believed by many doctors of the day that convulsions could be brought on by anything from "bad digestion" to exposure to loud noises or overly bright lights. Treatments for those babies who lived through a bout of convulsions could include everything from bloodletting via leeches to exposure to ammonia to the administration of purgatives, all of which could themselves be dangerous for young children.

Childbirth

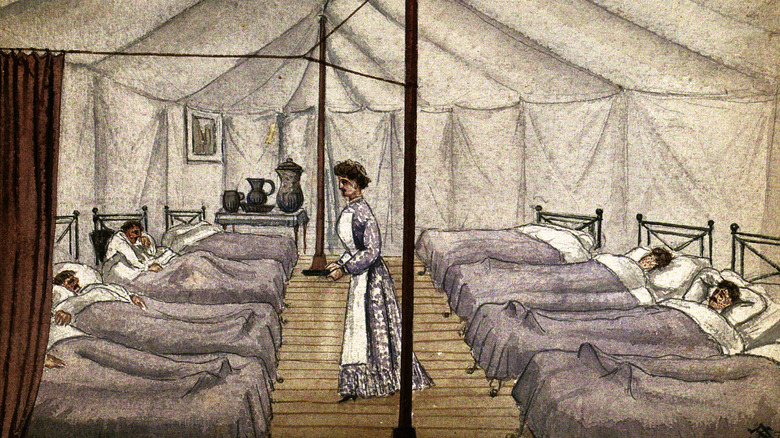

Though not quite so lethal a prospect as being born, giving birth was a deadly prospect for many mothers in the Victorian Era. As many as four to five out of 1,000 births resulted in the death of the mother, according to the journal Medical History. Boil that down a bit, and you get the figure of one out of every 222 births ending up with maternal mortality.

The reasons that childbirth could be deadly for Victorian mothers were many. Often an extreme loss of blood led to death during childbirth. Often diseases picked up during the mother's birthing process led to death. And in a cruel twist of fate, giving birth in medical facilities was much deadlier than giving birth at home, according to Mental Floss. This was the case because, in the 19th century, many of those in the medical field still lacked a clear understanding of how infections were spread, and common practices of our times, such as sterilization of tools and facilities and even basic hand washing, were rarely done. For reference, today the U.K.'s figure is around seven maternal deaths per 100,000, or one death per more than 14,285 births, via Knoema.

Scarlet Fever

According to Healthline, "Scarlet fever, also known as scarlatina, is an infection that can develop in people who have strep throat ... characterized by a bright red rash on the body, usually accompanied by a high fever and sore throat." The illness usually afflicts kids between the ages of 5 to 15, and today it is usually quick and easy to treat with a routine course of antibiotics. In the Victorian Era, however, it was quite often a death sentence for British kids.

In fact, as many as a third of children who came down with scarlet fever in those days would die as a result of their sickness, according to Quartz, with those younger than age 8 at the highest risk of mortality. Tens of thousands of youngsters died from scarlet fever during many single years of the 19th century, with 20,000 Britons succumbing to the disease in the year 1840 alone, as per statistics gleaned from Castle Bromwich Graveyard. And even those who did recover from the illness could have long-lasting maladies, such as permanent deafness, one of the most severe results for those who survived their affliction with scarlet fever (via Hearing Health Matters).

Pneumonia

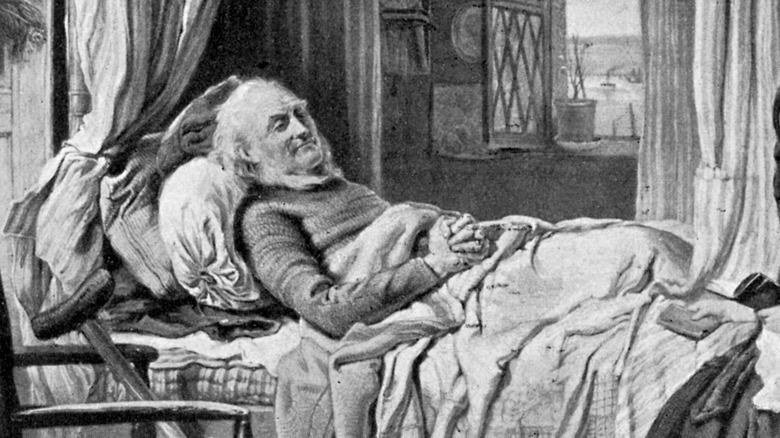

Pneumonia remains a common cause of death even well into the 21st century, but it was even more prevalent of a killer in Victorian times. The thing about pneumonia is that, in most cases of the day (and in many cases still), while it is often the technical cause of death, it almost always comes on only after the body has already been severely weakened by a different illness. According to Johns Hopkins Medicine, "pneumonia is an infection of one or both of the lungs caused by bacteria, viruses, or fungi," or, in other words, it is an infection that can be brought on by quite a diverse range of afflictions.

Because the onset of pneumonia usually came after a patient suffered with another sickness and because its onset often led to a swift and relatively painless demise, it was often called the "old man's friend" in the Victorian Era (via Social History of Medicine). But to be clear, it was by no means entirely painless or at all pleasant: A person who develops pneumonia experiences lungs filling up with fluid, phlegm, or pus, making it harder and harder to get oxygen into the body and effectively resulting in a drowning death, though one often precipitated by unconsciousness.

Dropsy

Dropsy was also a leading cause of death in the Victorian Era, despite the fact that it was a mere symptom of an underlying issue, not the killer itself. Today called edema, dropsy was (or is, rather, though by another name) a swelling of the body, often in the lower extremities or the hands — though any part of the body could become swollen — caused by an excessive retention of fluids, according to Medline Plus.

The actual causes of dropsy/edema are usually a partial or complete organ failure. It can be brought on by congestive heart failure, by the kidneys shutting down due to illnesses like diabetes, by liver failure caused by sickness or heavy alcohol use, or by other causes. Regardless of the underlying cause of the dropsy, it is a symptom of a severe, often deadly underlying cause, but in Victorian Era England it was often listed as the cause of death itself. The doctors of the day did at least understand that dropsy was an excessive accumulation of fluids, naming the malady for the Greek word for water, "hyrdrops," according to "The Cambridge World History of Human Disease."

Cholera

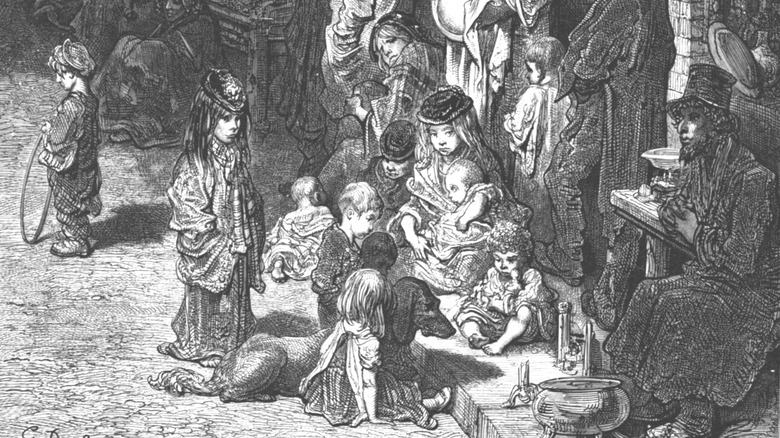

If you close your eyes and picture England in the 19th century, chances are good you'll call to mind images of finely dressed gentlemen and ladies strolling the grounds of elegant manors, of dashing hunters pursuing foxes through lush woodlands, of the pomp and ceremony of the royals, and of a generally lovely place, all told. But the reality was anything but lovely for many Britons of the day. Reading select passages from Charles Dickens can create a more accurate picture of the abject urban squalor in which many English men, women, and children lived during the Victorian Era — and with that squalor came sickness. One particular disease thrived in these close, highly unsanitary conditions, and that was cholera.

According to the Science Museum, the lack of access to clean water and the absence of effective sewage systems created an endemic of cholera in London in particular, which first reared its deadly head there in the 1830s. Those sickened with the bacteria causing the illness would have horrid diarrhea and vomiting, which led to life-threatening dehydration, and could also experience rapid or irregular heartbeats, fever, rashes, and total exhaustion. Barely understood and essentially untreatable at the time, cholera ravaged many cities of the day. Gradually, understanding of the disease would prompt improvements in civic sanitation infrastructure, a silver lining despite all the suffering and death.

Accidental Death

An accidental death can, by its very nature, happen to any one of us at any time and as a result of countless factors. Things were no different in Victorian England. According to "Changing Hands: Industry, Evolution, and the Reconfiguration of the Victorian Body," by Peter J. Capuano (via Victorian Web), factory workers were at particularly high risk for accidental death as there were essentially no safety measures in place to prevent accidents. In fact there were rarely ways to shut down machinery quickly, so in many cases what could have been an injury — though a catastrophic one to be sure — would result in death.

According to Chimney Solutions, chimney sweeps of the era, who were often young children, often became trapped inside chimneys and suffocated to death — a fate that saved them from the cancers often developed as a result of their work and would have later killed them anyway. Another surprisingly common cause of accidental death for younger Victorian Era Brits was drowning after falling through ice, according to York Cemetery. Other accidental deaths occurred around farming equipment, the ever more common railroads, as a result of horse and carriage accidents, and on it went.

Natural Decay

Not surprisingly, no one during the Victorian Era was immortal; everyone died eventually, and in many cases the cause of death was attributable to nothing more than a person simply growing old. The Victorians called death as a result of old age "natural decay," a term that might not be all that sensitive but is accurate in its own objective way. According to the University of Leeds, natural decay was given as the cause of death in countless cases during the 19th century, and the term was still in frequent use for much of the 20th century as well, despite its ultimately ambiguous meaning.

Today it's called "dying of natural causes," and such a death usually comes for people well into their 70s, 80s, or even 90s. In Victorian England, the onset of the natural decay preceding death was expected much earlier, often starting when someone was not much past 50 years of age. And while natural decay alone may have sounded like a sufficient explanation for a death back then, today one does not literally die as a result of advanced age, but, according to Business Insider, as a result of some other cause that the aged, weakened body cannot survive as well as it would have in younger, healthier years.

Smallpox

Today it is a medical success story par excellence: Smallpox has been eradicated from the human population at large for more than 40 years, the World Health Assembly having declared humanity free from the disease on May 8, 1980, according to the CDC. Granted, it took centuries to get there, and that was the case even though it was known that vaccinations could prevent smallpox infections for 200 years, give or take — note that as far back as the American Revolution the benefits of inoculation against the disease were clearly understood (via the National Parks Service).

But in Victorian England, smallpox was still very much around and very deadly, as it had been since antiquity. According to the U.K. National Archives, smallpox killed about 30% of those who caught the disease in the mid-1800s. Things got better after the year 1850 when the British government began mandating smallpox vaccinations for the populace, but in echoes of our times today, there were also many Brits who opposed vaccinations and refused to be inoculated against the disease for fear of side effects. Mandatory vaccination policies were dropped by the turn of the last century, arguably delaying the eventual eradication of the ancient disease.

Overdoses

Despite many fervent temperance movements that influenced many in Victorian Era England, the 19th century was a hard drinking time for many, and a drug-using time, as well. "The Victorian Yearbook" from 1889 compiled numbers from previous years, with the mortality rate increasing year over year.

According to the Bulletin of the History of Medicine, chronic alcoholism was a crushing condition for many Britons of the day, with premature death a regular result. While many succumbed to alcohol related issues like cirrhosis of the liver, the compounding issues were many, including essentially unrestricted access to strong drink, contamination present in improperly prepared booze, and accidents that occurred during drunkenness.

And according to Mental Floss, another substance was also quite the killer of the era: opium. Used in all sorts of "medical" applications of the day and abused recreationally as well, opium led to the premature deaths of tens of thousands of Victorian Era British folks. And many of them were entirely unwitting victims, in that they were kids. It was quite common in those days to drug kids with opium-derived tinctures in order to ease pain, induce sleep, or in some cases to simply force a young child into a stupor so he or she would not need tending while their parents worked away the hours of the days. Not surprisingly, little bodies did not do well dealing with hard drugs, and death often resulted.