Secret Meanings Hidden In Famous Works Of Art

Psychology Today says that when it comes to art, only humans create it. But here's the thing: They also add that if anyone were to take a long, hard look at the behavior of some animals, they do something that sort of lives next door to art. Take the birds who preen and perform, and who decorate nests in order to attract a mate. They're making something meaningful that moves the spirit of another, and isn't that what art is?

Humans have been creating works for a long time. According to the Smithsonian, what was believed to be the oldest piece of art ever discovered had been found on the wall of a cave in Indonesia. It was a huge depiction of a creature called a babirusa — also known as a pig-deer — and at the time it was painted more than 35,400 years ago, they would have lived side-by-side with the ancient humans who had painted the mural.

Researchers were able to tell a lot from the sketch, including the fact that the unknown artist had set out to draw a female babirusa — there were no tusks. Not all art is that straightforward, though, and as humankind has developed new techniques and skills for creating artistic masterpieces, it hasn't been unheard of for them to sneak some hidden meanings and messages into said works. Sometimes, it's taken centuries for critics, historians, and scholars to finally catch on to what an artist was really trying to get across in a work.

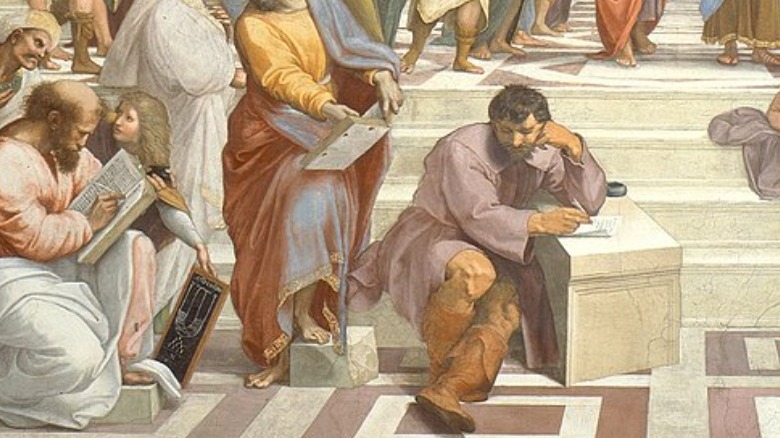

Raphael's The School of Athens

Raphael died in 1520, and according to the BBC, it took art historians about 500 years to notice a relatively tiny detail in The School of Athens. The work is in the Vatican, and it's meant to represent the philosophy texts found in the church's libraries. The then 20-something Raphael was doing some preliminary sketching when he realized he had a problem: All old Greek philosophers kind of looked the same. Rather than trying to come up with a way to identify them, Raphael decided to just sort of run with the chaos.

The result is that no one's ever been sure just who's who. There's one figure that might be Euclid, and it might be Archimedes. There's another that might be an Athenian general named Alcibiades, or Alexander the Great. But how do historians know that Raphael was vague on purpose? The inkpot, balanced on the edge of a table beside a man lost in thought.

The figure looks like Michelangelo, but the air of sadness about the figure and the mid-sentence pause suggest that he's a nod to a Greek philosopher called Heraclitus — and Heraclitus was most famous for his work (which has been lost in its entirety) on the fluidity of an ever-changing world. He's the one who said, "You cannot step in the same river twice," and that idea that forms the backbone of his work seems to indicate that Raphael 100% meant to be as ambiguous as he was.

Van Eyck's The Arnolfini Portrait

Jan van Eyck painted The Arnolfini Portrait in the 15th century, and at a glance, it's a perfectly ordinary piece depicting two people and a dog, standing in a bedroom. But there are some fascinating details that have spawned a ton of theories over the years — and as The Collector notes, they really are just speculation.

With a long-standing theory debunked in the 1990s, it's now thought that the two are Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and wife Constanza Trenta ... but there's a problem. Costanza died in childbirth in 1433, and the date on the painting is 1434. But! There are a few clues that seem to indicate that this is a memorial painting, and the woman is actually dead. In addition to the man seeming to hold the woman's hand even as it's slipping away, there's also a gargoyle beside her — not exactly a favorable portent. And neither is the dog at her feet, a creature long thought to guide souls into the afterlife.

Most fascinating of all is perhaps the mirror on the wall. The side facing the man is decorated with scenes from Christ's life, and the other side depicts his death and resurrection. The chandelier over the couple is similarly split: Over the man's head, a candle still burns — as does his life. On the other side, though, the candle is spent and all that's left behind are drips of wax. The flame over her head has burned to an end.

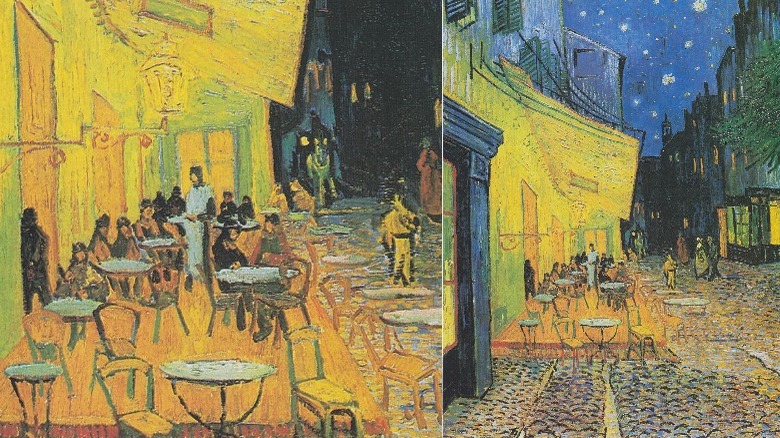

Van Gogh's Cafe Terrace at Night

Vincent van Gogh's most popular works are the sort of thing that every college student has on the wall of their dorm room. It's one of those pieces most have seen so many times that they might do little more than glance at it, but in 2015, art historian and researcher Jared Baxter realized something startling: Sitting among the cafe's tables were 13 people, including one long-haired, white-clad figure ... and one was stepping off into the shadows.

If that sounds vaguely familiar, that's because it should. Baxter argues that van Gogh included the group as an homage to Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper.

Baxter further says (via ArtNet) that at the time van Gogh was painting this particular work, he had written a letter to his brother talking about his "tremendous need for, shall I say the word — for religion." It's also not the only one of van Gogh's works that have been found to contain what UCLA professor Debora Silverman called "sacred realism," as she includes images such as the halo-like positioning of the sun in The Sower as proof that van Gogh's works can also be viewed as having a deeply religious meaning.

Caravaggio's The Supper at Emmaus

In 1601, Caravaggio was commissioned to do The Supper at Emmaus. The scene is out of the Gospel of Luke, and it's basically a post-Resurrection Christ breaking bread with disciples who don't recognize him until the moment captured in the painting. Straightforward enough, but according to the BBC, there's one tiny detail that makes it mean something revolutionary.

What is it? A basket of fruit sits at the edge of the table, and two wicker twigs of the basket are broken. Just a bit of realism, or something else? Something else: The twigs are bent in the form of a nearly complete Ichthys, the fish that believers once used to identify themselves in a world where they could be persecuted for those beliefs. (The shadow behind the bowl is also in the shape of a fish's tail.) That "nearly complete" part is significant, too. In order to identify themselves, ancient Christians would draw half of the Ichthys on the ground. It was a seemingly harmless sort of thing to absent-mindedly do, and only those in the know — true believers — would know to finish the drawing. It's suggested that Caravaggio is asking the viewer whether or not they would finish this seemingly innocuous symbol, and believe.

Interestingly, Caravaggio's tormented life got pretty hairy after that — he died mysteriously in 1610 — and when he repainted another version of the same scene five years after the first, the bowl and the Ichthys were gone.

Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel

It's difficult to imagine how many people looked up at the Sistine Chapel's ceiling over the course of 500 years — give or take. Shockingly, all of those people missed the fact that it wasn't just depicting some of the most important people and scenes of the Bible, but human anatomy, too. According to Scientific American, Michelangelo had a long-held fascination with anatomy — and at 17, he was dissecting bodies. He started work on the Sistine Chapel in 1508, and it wasn't until 1990 that a doctor named Frank Meshberger realized that he had designed the image of a God reaching out to touch Adam as having the shape of a cross-section of the human brain. Meshberger imagined that it was Michelangelo's way of suggesting God gave mankind intelligence, but since then, neuroanatomy experts from Johns Hopkins have found scores of other anatomical references.

God is right over the altar — and the odd appearance (inset) is explained by the fact that it's a pretty perfect depiction of another human brain and an optic nerve. The shape of a human kidney has also been spotted, a spinal cord appears in God's robe, and NBC says two doctors from Brazil found a human heart in the robes of the Cumaean Sibyl.

What does it all mean? It's been suggested that Meshberger had it backwards, and the cynical Michelangelo was suggesting God — and the Church — was a creation of the brain of mankind.

Michelangelo's Sistine Chapel

According to research done by Vatican guide Roy Doliner and Rabbi Benjamin Blech, there's a heck of a lot more on the ceiling than just Christian imagery. It started when he noticed two of the letters on the ceiling — aleph and ayin — were a Hebrew reference to Christ. They had only become visible after a restoration cleaned off centuries of grime, and it kicked off a massive investigation that turned up more.

Take his depiction of David and Goliath (left). They're positioned to form the letter gimel, which is connected to strength. He does it again with Judith (right): She's holding the head of Holofernes in the shape of another letter. That's het, which is connected to "loving kindness," says The Telegraph. There are a few other hidden messages, too. The prophet Zechariah was done in the likeness of Pope Julius II, and it's clear Michelangelo wasn't a fan — standing behind him is an angel making a gesture so obscene, it's mentioned in Dante's Inferno. (Doliner told The Wall Street Journal that he got away with it because the details were relatively small.) He also added some naked men wrapped in a very loving embrace, and the men? They were in heaven, an unthinkable idea in the mid-16th century.

So, what was the point of all this? Doliner suggests that Michelangelo wanted the ceiling to be a reminder that not only was Jesus a Jew, but that everyone would do well to remember that Judaism and Christianity go hand-in-hand: And, everyone's created in God's image.

Titian's Bacchus and Ariadne

It's easy to put history's greatest artists on a pedestal, to idolize them, and to forget that at the end of the day, they were just like everyone else. And — just like the majority of modern, 21st-century people — they probably thought fart jokes were super funny. When it comes to one in particular — Titian — he was such a fan he painted one into his Ovid-inspired Bacchus and Ariadne.

The painting depicts the moment when Bacchus first sees Ariadne, who Theseus has just abandoned on the island of Naxos. The god is in mid-air, and a position that's often lauded as the perfect expression of that moment of love at first sight, when everything seems to stop. But look beneath him, and a seemingly small flower beneath his feet suggests that he didn't jump into the air, but was instead lifted there by a massive fart.

The flower, says the BBC, is called Capparis spinosa, or the caper flower. It was widely used as a cure for excessive gas, and it just so happens to be planted alongside a satyr. These half-man, half-goat creatures weren't just followers of Bacchus, they were also infamous farters. Take a look at the expression on the face of this one — and the face of Ariadne, who's raising a hand as if to wave away the smell — and just try to argue that the entire moment isn't the aftermath of a god passing gas as only a god could.

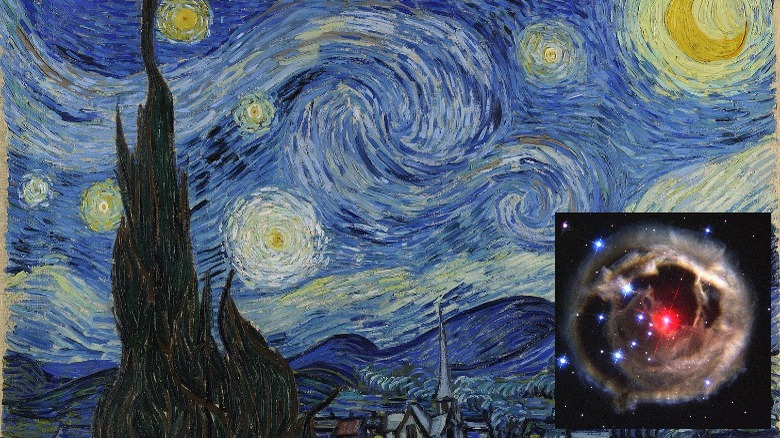

Van Gogh's Starry Night

Starry Night is the other piece by Vincent van Gogh that's on the wall of every college dorm room. The swirls in van Gogh's work — which, incidentally, was painted in 1889 — are iconic, and here's where things get weird. Concord Consortium research associate Natalya St. Clair says (via ArsTechnica) that the swirls are pretty common among Impressionist painters. It's used to indicate movement, but it wasn't until decades later that anyone realized van Gogh had painted something else, too — when NASA's Hubble Telescope captured an image (inset) that looked a lot like Starry Night.

The photo was of dust clouds swirling around a supergiant star, and far from looking "kind of" like Starry Night, it was precisely what van Gogh illustrated in Starry Night — along with Wheatfield with Crows, and Road with Cypress and Star. When a group of physicists got together for a project led by Mexico's National Autonomous University, they compared digitized versions of van Gogh's work with the images captured by NASA, and found that they were nearly identical on a shockingly precise mathematical scale.

The researchers also noted that the more precise paintings were done at a time when van Gogh's life was most "turbulent," and when things calmed down for him, the phenomenon — known as Kolmogorov scaling — disappeared. Marcelo Gleiser explained: "[It was] as if his mind somehow tapped into a universal archetype where ... the painter's brush and nature's brush became one and the same."

Bronzino's An Allegory with Venus and Cupid

An Allegory with Venus and Cupid is full of naked people having all kinds of sexy-time, there's a weird creepy guy looking in from above, and it's actually a condemnation of the sort of behavior that can make anyone come down with a nasty case of syphilis.

Wait, what?

According to a study published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, Angolo Bronzino's 16th-century work might look like it's all about the frolicking of cherubs, nymphs, and the goddess of love, but it's also a warning about what's going to happen to any person who similarly frolics. That creepy guy looking down on them is thought to be Father Time, revealing an action that isn't going to be fading away anytime soon. As for the others, they're actually depicted as showing some of the signs of syphilis — a new and, at the time, incurable disease.

One cherub has a rose thorn through his foot (detail, left), symbolizing nerve damage and an inability to feel various stimuli in the extremities. Another figure (right) — once thought to be Jealousy — shows all the signs of a secondary syphilis infection: His hair is falling out, he's missing fingernails, his eyes are red, and he's got a nasty discharge leaking from his gums. And then, there's the girl in green. She's beautiful and trying to tempt anyone who's willing with a honeycomb, but she also has the body of a monster. An allegory, indeed.

Durer's Young Couple Threatened by Death (The Promenade)

The prints of Albrecht Durer are unmistakable, and according to Artsy, they're what helped turn printmaking into a legit art form. Durer's Young Couple Threatened by Death (The Promenade) was done in 1498, and at a glance, it's a perfectly ordinary sort of depiction of a couple with eyes only for each other, being stalked by a creepy skeleton waving an hourglass. Durer was a dark sort of guy — and that's not all that's hidden in this piece.

MPR reported on an exhibition of Durer's work in St. Peter, Minnesota, and this piece came up — particularly, the ultra-scandalous couple. Wait, what? The dress that the woman is wearing is, historians say, illegal under Nuremberg's insanely restrictive clothing laws of the era. And we know they're in Nuremberg, because there's a coded reference to the city etched into the neckline of the dress.

Neat, right? There's one more thing, though. Those clothing laws dictated what people could wear based on their social and marital status, and according to the Dallas Museum of Art, the giant ostrich feather stuck in the man's cap was reserved for bachelors. So far, so good. But then, check out the hat his lady's wearing. Those bonnets were worn by married women, so the seemingly innocent etching is actually depicting an adulterous affair.

The medieval era's snails

The medieval manuscripts of the 13th and 14th centuries were done at a time when everything was copied by hand, and scribes would often add their own flourishes around the borders of the text. It's called marginalia, and some of it is downright bizarre. According to The British Library, there's one image that shows up a lot: knights fighting snails. They show up so often that it's clear they mean something, but no one's entirely sure what.

There are some fascinating theories, though, including one that suggests the snails were meant to represent a group called the Lombards. They were widely condemned for all kinds of bad behavior, often called "non-chivalrous," and according to Britannica, the 6th-century era of Lombard rule was insanely chaotic and violent — even for the Middle Ages. so that kind of makes sense — especially considering they were eventually ended by the joint forces of Charlemagne and Pope Adrian I.

Not everyone agrees, though. Some think the snail is meant to represent the temptation of women, while other scholars suggest it may have been a way of depicting the struggles of the lower class against the aristocracy. Another theory is that it is exactly what it looks like — images drawn by scribes sick of having snails eating their way through their garden, so they're fantasizing about knights riding to rescue them from this ravenous garden pest. What does it really mean? No one knows!

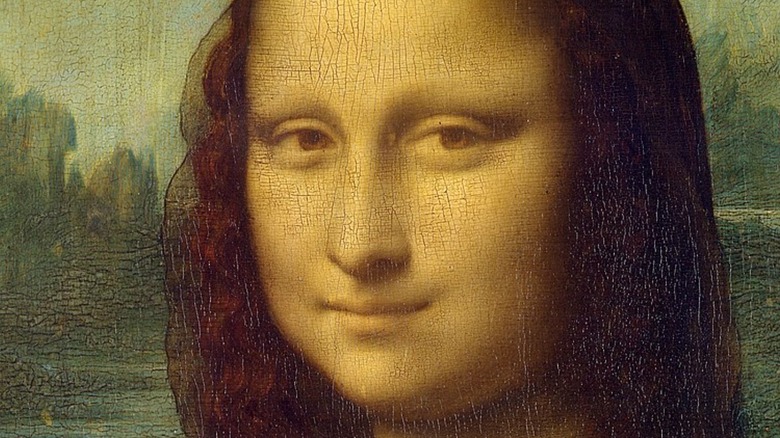

Leonardo's Mona Lisa

Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa is so famous, it's easy to think that everyone has seen everything there is to see. While most of the focus is on her enigmatic smile — which reportedly drove at least one person to suicide — others have singled out her hands and eyelids as being the thing that gave the piece an aura of the supernatural. According to the BBC, it's her hands — and what they're on — that gives the entire piece new meaning.

The Mona Lisa is sitting in something called a pozzetto chair, which translates to "little well." And that changes a lot — it's no longer a portrait, some contend, but a landscape — and she's the central part of it. The river behind her doesn't just flow past her, it appears to feed into her "well." That's taken a step farther when adding in the fact that she's wearing a dress that's the color of algae, and the murkiness of the entire piece is likely exactly what Leonardo intended.

It turns out that the idea of a woman at or as a well is deeply spiritual. It connects women to the forces that sustain the planet and everything on it — water — and images of Christianity's women (such as Rachel, Rebekah, and even the Virgin Mary) at wells are plentiful. Water, the idea goes, can quench both physical and spiritual thirst, and by Mona Lisa's careful seat within a living well, Leonardo has turned her into "living water."

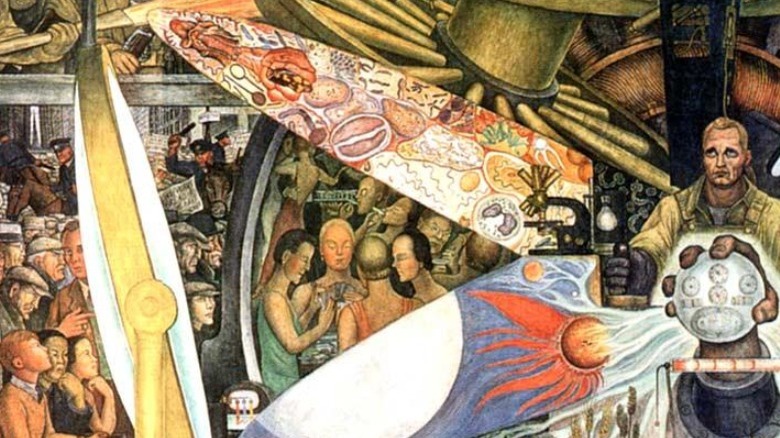

Rivera's Man at Crossroads/Man Controller of the Universe

The thing about making an enemy of artists and authors is that at some point, you're going to show up in their work somewhere — and there's a good chance it's not going to be flattering. The story, says Daily Art Magazine, started when Nelson Rockefeller hired Diego Rivera to design and paint a mural for the Rockefeller Center. Rivera created a series of three murals. Man at Crossroads was approved, but once Rivera started working on the commentary about the differences between socialism and capitalism, the papers were all over that. Amid accusations that the Rockefellers were outfitting their building with some major communist propaganda, Rivera first added Vladimir Lenin to the mural, and then, was paid and sent on his way.

That was in 1932: Now, fast forward two years. Rivera painted Man, Controller of the Universe as his definitive work highlighting the differences between communism and capitalism. There's a shocking amount going on in the work, and it's easy to miss the addition that's meant as a massive middle finger to the Rockefellers and the fate of his earlier work — which was completely destroyed.

John D. Rockefeller is depicted on the mural ... although perhaps not in the way the Rockefeller family might have wanted. Not only is he drinking in a nightclub with a mysterious woman, but just in case that wasn't a clear enough message, Rivera added a petri dish with bacteria in it. The bacteria? Syphilis.