Seriously Disturbing Moments In G-Rated Movies

Ever since it was introduced in 1968, the MPAA's G rating has assured audiences that the movie they're about to watch is good, wholesome entertainment that the whole family can enjoy. Or at least, that's the idea. In practice, the G rating is usually reserved for kids, an arbitrary standard that gets slapped on animated films meant for a couple hours of colorful distraction.

Every now and then, though, something slips through that goes way past what you'd expect and right into some truly disturbing stuff. Get ready to revisit your most memorable childhood traumas (and learn about a few more obscure bits of weirdness) as we dive into the most disturbing moments to ever hit theaters and still be rated G.

All Dogs Go To Heaven: Charlie goes to Hell

Despite the cute, reassuring title, Don Bluth's All Dogs Go To Heaven presents a vision of the afterlife that is truly messed up. That's not really a surprise, though — this entire list could just be choice bits of existential horror pulled from Bluth's extensive filmography. Suffice to say that this isn't the last time you'll be seeing him on this list.

It is, however, the only movie we're aware of that starts with the dog getting killed and then just gets even more harrowing from there. Not just killed, either, but drugged and subsequently murdered by his business partner before managing to return to Earth to get revenge in what we can only assume is direct defiance of God himself. In other words, by the time this movie has gotten to the point where it introduces its main plot, we have learned that A) all dogs go to Heaven, B) dogs are also fully capable of murder and motivated by both profit and personal hatred, which leads inevitably to C) Heaven is, statistically speaking, just full of dogs who have committed the sin of murder. And we haven't even gotten to the human characters.

In the end, though, that's all just existential dread that comes when you really start thinking a little too hard about the mechanics that allow a dog voiced by Burt Reynolds to Cannonball Run his way back to this mortal coil. What's disturbing in the moment is an extended nightmare sequence where Charlie B. Barkin — who has been told he cannot return to Heaven — is faced with the prospect of an eternity in Hell. Like, straight up lake-of-fire Hell, where Satan rises from the flames as a dragon (as seen in Revelation 20:2) and tortures him with demons. So yeah: messed up.

Mary Poppins - Gaslighting the children

Speaking of Mary Poppins, most of us remember that film for its delightful, charming adventures, like jumping into a chalk drawing or gallivanting on rooftops with a troupe of filthy chimney sweeps. What's far less remembered, though, is Mary herself full-on gaslighting the Banks children.

After they get back from a day spent tap-dancing with penguins and watching Mary win a race on a carousel horse that she brought to life with her boundless magical powers, the Banks children are understandably excited. Mary, however, is all business, telling them to chill out and go to sleep, saying that nothing of the sort happened while they were out that day and then chiding them for their overactive imaginations. When they plead with her to acknowledge that their experiences — the experiences that we, the audience, also saw — she insists that they're lying and says she'll punish them if they continue to speak what they, and we, know is the truth. This is classic gaslighting.

To be fair, though, it's not as bad in the movie as it is in the book. At least here, outright denying the evidence of the children's senses is an isolated incident. In the original, it happens all the time, and is usually accompanied by Mary acting completely disgusted that the children would even suggest that they'd seen something weird. Like, say, a grown woman flying through London on her umbrella.

The Last Unicorn: That tree

Rankin/Bass Productions is best known for its roster of stop-motion TV Christmas specials like Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer and Santa Claus Is Coming To Town, but it's also made a couple forays into theatrical films, too, which is where things get really weird. In 1982, for instance, it followed up a successful animated version of The Hobbit by adapting another fantasy book: Peter S. Beagle's The Last Unicorn.

The title and the character designs might imply a gentle but tear-jerking fantasy, but this thing goes off the rails real quick once the eponymous talking unicorn gets captured by yet another creepy carnival and is imprisoned alongside a harpy. Those of you schooled in mythology might be surprised to find out that the MPAA had zero problems with Rankin and Bass sticking to the concept of a bird lady with pendulous naked breasts, but honestly? Bird nipples were the least of their worries.

The real weirdness comes from the wizard Schmendrick and his tendency to accidentally turn things into human women. The main plot comes from him doing this to the unicorn, but along the way, he also brings a tree to life and, much to everyone's surprise, it turns out to be an extremely randy bit of plant life. Congratulations to anyone who has the very specific desire to be crushed to death between two giant wooden boobs: here's your new favorite movie.

The Secret of NIMH: The deadly burden of sentience

Picking out a single disturbing moment from The Secret of NIMH — Don Bluth's directorial debut from 1982 — is pretty difficult. There is, for example, the climactic fight scene, in which a ruthless rat named Jenner is dueling against the heroic Justin and just sort of incidentally turns and slits another rat's throat with the tip of his sword, leading his victim to stab him in the back with a thrown dagger just before dying face-down in the mud. In any other children's movie, that would rank as the single most horrifying thing to happen. In Secret of NIMH, it might not even be in the top three.

The real creepy stuff comes when Mrs. Brisby and the audience learn the secret origin of our anthropomorphic mouse pals. Under normal circumstances, we could probably just take rats that talk, wear clothes, and murder each other with swords as a given, but here, it turns out that they're the direct result of Man meddling in the domain of God. As the product of experiments by the National Institute of Mental Health, they were given drugs that increased their intelligence, which then led to an escape attempt where most of the mice immediately died, having just gained the capacity to truly understand what death was.

The more you think about it, the weirder that gets — especially when you take that premise to its logical conclusion and start wondering what kind of hellish laboratory produced Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck.

We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story: Professor Screweyes' nightmare circus

If you haven't seen We're Back, there's a good chance you won't believe us when we describe the plot. If you have seen it, you'll be relieved to know that it's a movie that actually does exist and isn't just some fever dream that you had while jacked up on NyQuil and peyote.

The basics are as follows: after kidnapping a bunch of dinosaurs from prehistoric times, a space weirdo named Captain Neweyes gives them Brain Grain, which makes them smart and friendly, and, in the case of a T. rex named Rex, gives him the melodic singing voice of John Goodman. He does this so that he can give modern-day kids the chance to meet real dinosaurs. Unfortunately, he has a twin brother named Professor Screweyes — one of his eyes is a literal screw that's been driven into his face that he uses to hypnotize people and dinosaurs — who wants to steal the dinosaurs, revert them back to jurassic savagery, and put them in a circus so he can terrify his customers. This is, for the record, a way worse business plan than just giving live dinosaurs to a natural history museum.

There's some other stuff going on, too, like a couple kids with hilariously thick Noo Yawk accents who get turned into chimpanzees at one point, but for a movie about singing, dancing dinosaurs, the part where Rex devolves into savagery and almost eats a crowd of people who are trampling each other in a panic as they try to escape is certainly the most disturbing. Wait, no, strike that. It's the second most disturbing, right after Rex's musical number about how much he wants to eat the '90s.

Toy Story: Sid's toys

There's a good chance that Toy Story's Sid Phillips is the single most terrifying villain in Disney's entire filmography, and considering that also includes Judge Doom, a character who literally does nothing but murder cartoon characters and shoot knives out of his giant red eyes, that's saying something.

The thing is, while the major threat in the movie involves him attempting to launch Buzz Lightyear into space with the help of some fireworks — actually a pretty common tactic for kids who wanted to add a little drama to their back yard GI Joe adventures — Sid isn't just destructive. He has also created toys, and that's where things get truly disturbing. They're clearly designed to be freakish, led by the severed head of baby doll with its hair torn out and a missing eye that's been grafted onto a spider-like body made from a construction set, with the rest of them equally Frankensteined together from bits and pieces of other destroyed toys.

That's creepy enough, but what really puts it over the top is our knowledge that all of these toys are secretly alive and were aware of their mutilation at Sid's sinister craft table. It also raises the question of just where that sentience comes from. The baby doll head retaining its knowledge kinda makes sense, but one of those things is just Barbie legs on a fishing pole, and just trying to imagine what kind of tortured existence that thing has when it's brought to life is truly skin-crawling. No wonder Sid's own creations elected to drive him mad with the knowledge of his sins.

The Adventures Of Mark Twain: Angel Satan

Just ... just watch the clip. It's the weirdest thing you will see today and possibly in your entire life.

Even at its most basic, The Adventures of Mark Twain is a weird one. The plot finds Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn, and Becky Thatcher hitching a ride on their literary creator's airship as he attempts to keep an "appointment" in space with Halley's Comet. Even keeping in mind that the "appointment" is Twain's own death — he was born and died in years that the comet passed by Earth and always said he hoped to do just that — it sounds like it could be a pretty fun romp full of jumping frogs, river hooligans, and wry commentary. It is not. It is terrifying.

In addition to Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer, director Will Vinton and writer Susan Shadburne decided to draw inspiration from one of Twain's later works, The Mysterious Stranger, and make it way creepier than a story about three teenagers meeting Satan on the road was to begin with. For starters, the original didn't take place in a pocket dimension, and Satan wasn't a headless nightmare monster with a twisting drama mask for a face. That stuff is all exclusive to the G-rated film version. You know, for the kids.

Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory: The psychedelic terror tunnel

1971's Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory has been an almost universally beloved children's movie for nearly 50 years, and there are a lot of great reasons for that. It's got catchy songs, a decent (if harshly judgmental) moral, spectacular fantasy visuals and, perhaps most important of all, Gene Wilder in the title role doing his level best to walk a razor-thin line between friendly and terrifying.

This is, after all, a movie where most of the lucky children end up meeting horrible fates at the hands of a factory that never even heard of OSHA. (Let's be real, though: if Augustus Gloop couldn't stay away from the chocolate river for one minute, he probably deserved what he got.) Wonka himself is far creepier than any ironic punishment his factory could contain, except maybe sending Violet Beauregarde to be juiced by Oompa Loompas. The climax of the film hinges on him manipulating and lying to everyone around him as a test to find a worthy replacement, and Wilder legendarily came up with the famous scene where Wonka emerges from his factory with a limp before falling into a somersault himself so that "from that time on, no one would know if I was lying or telling the truth."

That said, he's never creepier than when he takes the children through an already creepy tunnel lit by multicolored strobe lights and stock footage that includes a worm crawling over a dead man's face and a live chicken having its head cut off with a meat cleaver. Throw in Wilder's monotonic singing, which builds to a fever pitch of screaming a poem about uncertainty, and you have one of the greatest nightmares ever put on film.

Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day: Heffalumps and Woozles

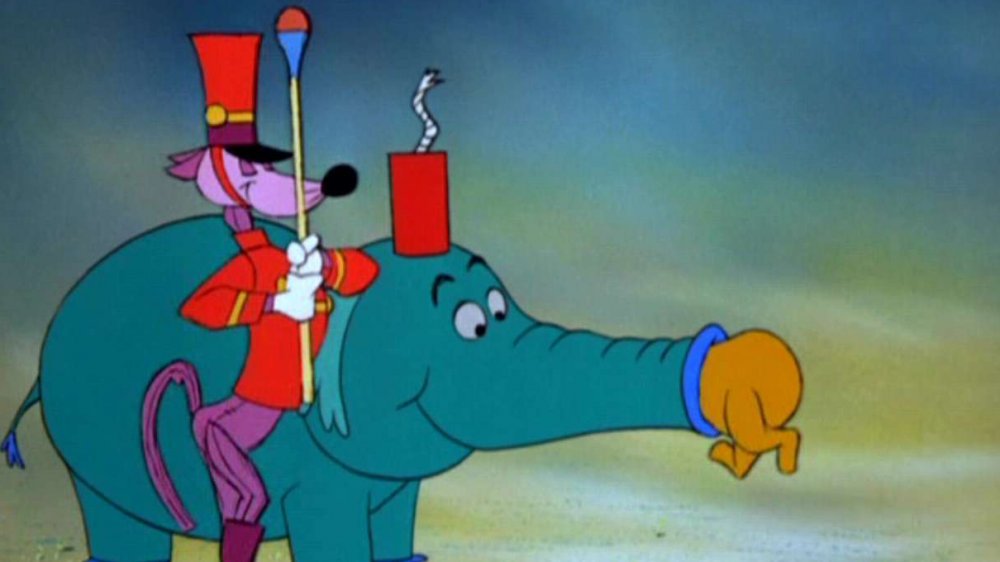

Originally released as a short film in 1968, Winnie the Pooh and the Blustery Day would go on to win the Academy Award for Animated Short Film and would return to theaters almost a decade later in The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh anthology film. Both times, it got a G rating, which makes sense. It is, after all, a charming story of stuffed animals having some gentle fun.

Except for that one part where Pooh is wracked with nightmares and terrible visions of horrifying creatures emerging from the shadows to mutilate and destroy their own bodies in an attempt to steal the only thing in the world that he actually loves, that is.

Maybe we're overselling things just a bit. In all honesty, the "Heffalumps and Woozles" song isn't actually scary, and even "disturbing" feels a little off. It does, however, follow the extremely weird logic of a dream where elephants (heffalumps?) drink honey (hunny?) through their noses until they explode, and where dancing creatures just randomly turn into shapes and then get furious with the viewers for watching for a second before they go back to having fun. Frightening? Maybe, maybe not, but it's definitely the kind of dream that leaves you feeling uneasy for the rest of the day, unable to shake the sight of an elephant with a stick of dynamite stuck through its head happily blowing itself up because it wants to steal your food.

The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T: Surrealist fever dream

To be totally transparent, The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T isn't actually rated G. Released in 1953, the film predates the MPAA's modern rating system, including the G rating, which wouldn't even start to be put into place until the mid-1960s. Instead, it was released under the Hays Code, the extremely restrictive set of guidelines that also affected other movies that might seem conspicuously absent from this list, like Bambi's mother famously being shot down by hunters in Bambi or the deeply weird "Pleasure Island" sequence in Pinocchio.

For this movie, though, we're willing to make an exception because you have to see this movie. It's the only feature film written by Theodore Geisel, better known as the prolific children's author Dr. Seuss, whose first draft of the script came in at a whopping 1,200 pages. Like most of his work, there was a deeper meaning, dealing with fear about the arms race and nuclear annihilation that came into being after World War II, but it's all viewed through the lens of the nightmare of a young boy named Bart who's sick of taking piano lessons from his teacher, Dr. Terwilliker, and finds himself in a strange land where Dr. T wants to dominate the world by having 500 children play an endless piano keyboard in unison.

The problem — or possibly the best part of the movie, depending on how you look at it — is that translating Seuss's whimsical designs into live action makes them seem downright Lovecraftian. The sets are built to look like impossible angles, and Bart spends most of the movie in a hat with a disembodied hand mounted on top before defeating his nemesis with the threat of atomic destruction. It's one of the weirdest movies ever made and absolutely worth watching. Just don't be surprised if your dreams get weird after seeing it, too.

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang: The Child Catcher

If it's been a while since you've seen it, it's worth noting that Chitty Chitty Bang Bang is both way weirder than you'd expect a Mary Poppins-esque romp about a flying car to be, and exactly as weird as you'd expect from a children's story written by the creator of James Bond, right down to the romantic lead being named "Truly Scrumptious." Ian Fleming was many things, but "subtle" was not one of them.

After all the bizarre set pieces set in a candy factory or a circus comes the trip to the vaguely Eastern European country of Vulgaria (there's that subtlety again). This particular sequence takes up the last quarter of the film, and the conflict is mostly based around Vulgaria's counterintuitive decision to literally outlaw children. It's a goofy idea, but it's made incredibly creepy with the introduction of the Child Catcher, a character created for the film by screenwriter Roald Dahl because why not terrify as many children as possible? This weirdo brings plenty of upsetting imagery along with him — like the entire main cast disguised as jacks-in-the-box — but it eventually involves him quite literally luring children into his van, er, horse-drawn wagon, only to reveal that it is a cage.

The weirdest part, though, comes right after his introduction. Not only does he threaten to have a toymaker's eyeballs made into earrings, he also describes his method for finding children in exactly the same terms that Christoph Waltz's character uses in the opening of Inglourious Basterds. No, really: "You have to know where to look. Like cockroaches, they get under floors." Oh, and he's also waving around a giant metal hook the whole time. You know, for children.

Wild Hearts Can't Be Broken: Blinded by diving horses

The G rating isn't just reserved for animated films. There are plenty of live-action movies, including ones that aren't targeted at kids, that manage to slide through the Motion Picture Association of America with a stamp of approval, ready for General Audiences to sit down and have a nice, fun time at the theater. Or, in the case of Wild Hearts Can't Be Broken, to see a horse stumble off a 40-foot tower and wind up blinding a girl.

The movie is loosely based on the real-life story of rider Sonora Webster Carver, although according to her sister, she would later remark that "the only thing true in it was that I rode diving horses, I went blind, and I continued to ride for another 11 years." The incident she's referring to happened in the 1930s, when she hit the water with her eyes open during one of the acts. The force detached both of her retinas. The movie is presented as an inspirational tale of a woman who overcame a disability to keep on jumping horses off high objects.

If that wasn't disturbing enough, try the fact that diving horses were actually a thing. William "Doc" Carver — who earned his nickname as a dentist, not as, you know, anyone who should be telling people it's fine to ride a horse off a cliff — came up with the idea when his horse fell off a bridge, apparently deciding that this was something people wanted to see. They did; the diving horse act lasted until the 1970s. There was even a plan to revive it in 2012, which was shot down in what the president of the Humane Society of the United States called "a merciful end to a colossally stupid idea."

The Hunchback of Notre Dame: Hiding sins from the eyes of God

Disney's 1996 animated Hunchback of Notre Dame is not a good film. It stands out as the weirdest oddball in an era that dropped animated classics like The Little Mermaid, The Lion King, and Mulan, mostly because it has what might be the greatest extremes of tonal whiplash ever committed to film. Seriously, this is a movie where Jason Alexander plays a talking gargoyle who cracks fart jokes, and where the villain's driving motivation is his fear that his uncontrollable lust will result in being damned to an eternity in Hell. It's a weird one.

It sets the tone right up front, too, in the sweeping musical number that (literally) kicks things off and gives us the backstory for the ... romance? Adventure? Morality play? Whatever it is, this is the origin story, where Frollo chases down Quasimodo's mother and puts the boots to her, causing her to crack her head open on the steps of Notre Dame. He then attempts to drown an infant before being stopped by a priest who sings/bellows at him about how no matter what he does, he cannot hide his sins from "the eyes of Notre Dame," represented here by a statue of the Virgin Mary holding baby Jesus. You know, a mother and child, like the ones Frollo just straight up kicked to death and then tried to drown? Like that, but with the judgment of the almighty.

The death of a parent isn't exactly a rarity in a Disney film — it's basically a requirement, actually — but those deaths are often more abstract, like the unseen shipwreck in Frozen. There are definitely more visceral deaths, like Mufasa's trampling in The Lion King or the infamous murder of Bambi's mom, but dropping a brutal killing on the steps of a church into the first five minutes of a cartoon for babies? That's some next-level stuff.

Little Nemo: Endless Nightmare

Winsor McKay's Little Nemo in Slumberland comic strip is often regarded as one of the earliest high points of the medium, thanks to its surreal, dreamlike imagery that broke out of panels and spread across the page in ways that would've been innovative in the '40s, let alone when it started in 1905. It's also a perennial favorite for adaptations for children, having been the inspiration for everything from a full-length opera to a weird NES game. Oh, and also a G-rated anime film from 1989 that opens with every major nightmare you've ever had, all happening at once.

1989's Little Nemo: Adventures in Slumberland kicks off its charming adventure with the title character flying on his bed through the shattered towers of a ruined city. If the sight of what looks like bombed-out ruins from a Fallout game weren't bad enough, there's also the added creepiness of a backward clock tower with hands that lurch forward, just in time for Nemo to drop out of the sky, plunging into the same kind of seemingly endless fall that's synonymous with nightmares. Then, just for a little extra fun, he's chased by a terrifying train that he can't escape, hounded into a vaguely disturbing version of his own house where his mother won't look at him.

Later on in the film, a few of Slumberland's residents are attacked by a formless mass of shadows with a thousand glowing eyes, but honestly? Compared to the all-too-familiar night terrors of the opening sequence, Lovecraftian horrors are downright pleasant.

Planet of the Apes: You maniacs!

Here's a weird thing about the "G" rating: it used to be a lot more common than it is now. That's partly because there used to be fewer ratings — PG-13 wasn't introduced until 1984, when someone at the MPAA saw Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and decided that maybe you should be a teenager before you were allowed to see someone get their heart ripped out — but it also has to do with changing ideas of what was appropriate for "General Audiences." Before it became known as the rating exclusively for kids, there was a much broader idea of what that "G" rating meant.

The best known example of this loose interpretation might be Gone with the Wind, but it's also worth noting that 1968's Planet of the Apes also managed to secure a G rating. Looking back, that's not terribly surprising, what with all the corny costumes and scenery-chewing acting. Until, that is, you remember that the movie ends with someone shouting in absolute horror at the revelation of complete nuclear annihilation of the human race.

You, uh ... don't want to throw some parental guidance on that one? Not even when Charlton Heston is shouting "damn you all to hell" at the people responsible for apocalyptic warfare? No? Okay, MPAA. Your call, not ours.

Anastasia: Drag Rasputin to Hell

The fact that Anastasia exists at all is pretty surprising. Seriously, this is a kid-friendly animated comedy with a funny talking animal sidekick that is actually about the brutal execution of Tsar Nicholas II and his family during the Russian revolution, in which the heroes are running an elaborate con and the villain is the 20th century's most sinister mystical figure. That is a premise that had to be approved by so many people before it was made, and every one of them signed off. Catchy songs, though.

From a historical standpoint, the most disturbing element is probably the aforementioned execution, but in a show of restraint that you wouldn't expect from Don Bluth, that actually isn't seen, and is only vaguely hinted at by the presence of a genuine, torches-and-pitchforks mob assaulting the Winter Palace while singing a jaunty tune. Instead, the movie builds to a truly buckwild climax in which we get to see a man dragged to Hell to face eternal torment.

Early on, we see Rasputin selling his soul to the Devil in exchange for mystical power, and at the end of the movie, the bill comes due. When Anastasia stomps on Rasputin's phylactery, the source of his hell-born power, it shatters, leading to a quick but horrifying sequence where his flesh liquifies and melts from his bones, leaving behind a glowing green skeleton that crumbles to dust. Watch closely, and you can even see his eyeballs falling out. It's like if the end of of Raiders of the Lost Ark was animated by the guy who made The Secret of NIMH, which is the only way that scene could get scarier.