The Untold Truth Of The Dewey Decimal System

In 1906, according to Pratt Institute, the American Library Association (ALA) requested the resignation of its founder. Just the year before he had caused public outrage by circulating offensive ads for the Lake Placid Club — his self-proclaimed "haven" from "Jews" and "consumptives." Now he had sexually harassed four of his colleagues on the 10-day company cruise. It was not his first offense.

He was the (former) New York State librarian, the creator of the revolutionary classification system for modern public libraries, and he had co-founded the ALA at 25 years old (as would later be documented by the Library of Congress). He had founded the Library Bureau, the New Library Journal, and the nation's first public library school, the School of Library Economy at Columbia College, where he had, of course, also served as head librarian (per San Jose State).

But none of that mattered. Over the years, his misogyny, antisemitism, and predatory behavior had only gotten worse (via the book "Irrepressible Reformer"). The ALA could no longer turn a blind eye to the man's increasingly rabid (and increasingly public) misogyny, antisemitism, and predation— even if that man's name was Melvil Dewey.

'A mercurial young boy'

Melvil Dewey was born Melville Dewey on December 10, 1851. From a young age, Dewey was determined to solidify his own reputation as a "reformer." While the library system attributed to Melvil Dewey has established a standardized method of classification now used in over 115 countries (according to OCLC), Dewey used the repute he gained from his creation (including, as Slate noted, his role as New York State librarian) to terrorize young women and exclude nonwhite people from access to power. His legacy is more one of regression than reform.

In 1876, Dewey published "The Dewey Decimal System Classification and Relative Index" (per Britannica) while working at Amherst College. According to Pratt Institute Libraries, the Dewey Decimal System (per Dewey himself) was largely based on existing systems devised by William Torre Harris and Natale Battezzati. After drawing from this "fruitful source of ideas" (as he dubbed Battezzati), Dewey wasted no time formally codifying the system with his own name, copyrighting it in 1876.

Dewey went on to accumulate prestige with the establishment of multiple institutions, including the School of Library Economy at Columbia University (founded in 1887, per American Libraries Magazine) and, most famously, the American Library Association (founded in 1876, via ALA). The ALA went on to oust Dewey, its own founder, in 1906 (via History) — a testament to the magnitude of his misdeeds. However, the story of what led to Dewey's rebuke by high society was a much longer one in the making.

Hostility, harassment, and a culture of abuse: Dewey's School of Library Economy

Although Dewey's misdeeds were well-known to his contemporaries, little was heard of them until after his death. Wiegand, Howe, and Plotnik's biography of Dewey, titled "Irrepressible Reformer: A Biography of Melvil Dewey," casts an unflattering light on his legacy as an adamant antisemite and serial harasser of women.

According to "Irrepressible Reformer," Dewey used the School of Library Economy (which is often praised for its role in women's education) as a sort of hunting ground for women he would later come to prey upon. Although a longstanding rumor that Dewey required school applicants to self-report their bust sizes was disproven, the culture of harassment at Dewey's school was well-established (as noted by Mental Floss). According to American Libraries, over 90% of accepted students were women, who, as Dewey once remarked, could work just as well as men but be paid less (per Jill Sherman's Dewey biography "Melvil Dewey: Library Genius"). He also required all prospective students to submit their portrait. In regards to this practice, Dewey reportedly explained that "You can't polish a pumpkin" (presumably in regards to female librarians' appearance, as Wiegand, Howe, and Plotnik note).

The Lake Placid Club Affair and Dewey's Antisemitism

The scandal that would come to mark the beginning of Dewey's downfall would surround the Lake Placid Club, a New York resort Dewey kept as his self-proclaimed haven from "Jews" and "smoking women." The retreat for white elites (once home to guests such as Theodore Roosevelt) was, in no uncertain terms, established by Dewey to be exactly that — whites-only, no exceptions. Dewey's antisemitism was extreme even for the early 20th century, devolving from "fixation" into outright paranoia. According to "Irrepressible Reformer," Dewey purchased the land surrounding his resort for the explicit purpose of ensuring that "Jews wouldn't buy it," as American Libraries magazine reported.

According to "'Jew Attack': The Story behind Melvil Dewey's Resignation as New York State Librarian in 1905" (published in American Jewish History and posted at JSTOR), the club's "No Jews" policy was discovered firsthand by Henry Leipziger, a librarian hoping to attend Library Week in 1903 at Lake Placid. The policy would later incite outrage when Dewey himself exposed his antisemitism by circulating pamphlets promoting Lake Placid Club. "No Jews or consumptives allowed," the ads boasted. Although Lake Placid's white supremacist policies were no secret to its members, the message was enough to inflame even the "whites-only" political climate of the early 1900s. According to Pratt Institute Libraries, a petition was circulated in 1904 calling for Dewey to resign as New York State librarian. The Board of Regents, although refusing to force out their founder, issued a statement denouncing him in 1905 amid the chaos of yet another scandal.

The nightmare cruise to Alaska and Dewey's inevitable downfall

Dewey's eventual downfall, although sparked by one controversy, was really the result of many. His legacy was characterized by longstanding patterns of predation, discrimination, and harassment in nearly every sphere of his life. One of many incidents involved Dewey sexually harassing his stenographer (to whom he was later ordered to pay $2,000, according to Mental Floss). Two of his assistants reported being subject to "unwanted touching" on multiple occasions, which his colleagues are quoted as saying was "a known fact" (per "Irrepressible Reformer" and American Libraries). He was even accused of behaving inappropriately toward his daughter-in-law, eventually alienating him from his own son. In an era when sexual harassment allegations were not at all uncommon, the fact that Dewey's behavior was despicable even to men of his time is remarkable to say the least.

Yet the attack which Dewey perhaps came to regret occurred in 1906 on an American Library Association cruise to Alaska (recounted by "Irrepressible Reformer" and American Libraries) with plans to outline future plans for the ALA. Throughout the course of the 10-day cruise, Dewey sexually assaulted no less than four of his colleagues. With nearly everyone at wit's end, it was time for the founder of the American Library Association to be ousted from his role. According to Wiegand, Dewey resigned as New York State librarian in 1905. He would resign from the American Library Association one year later.

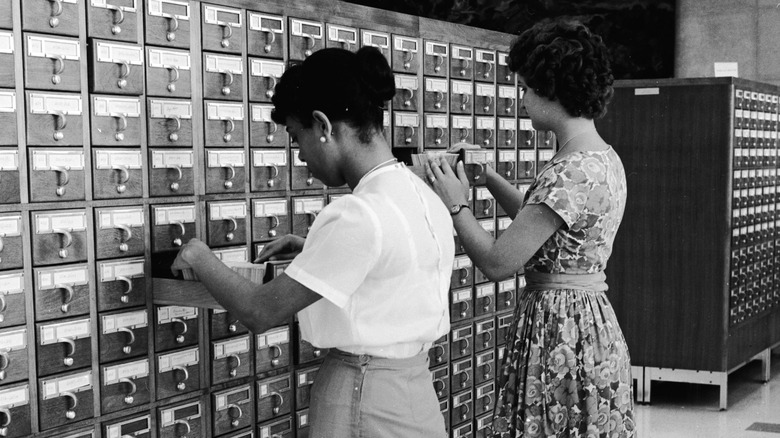

'Decolonizing' the system

In 1930, Dorothy Porter of Howard University initiated a project to "decolonize" Dewey's classification system (as noted by Smithsonian). It was a multi-coalition effort aimed to catalog the works of Black Americans in a logical way, rather than Dewey's system of cataloging everything from Black-authored poetry to Black-authored romance under "International Migration and Colonization," according to Pratt Institute. According to Publisher's Weekly, the American Library Association removed its founder's name from the "Melvil Dewey Medal" in 2019, renaming it the "Medal of Excellence."

In "Bringing Harassment Out of the History Books" in American Libraries magazine, author Ann Ford and biographical historian Wayne Wiegand say it took decades for the details of Dewey's misdeeds to emerge to the public. Despite isolated efforts to disassociate from Melvil Dewey, the institutions he formerly headed, some academics (including Wiegand) argue they have done little to grapple with their own role in his legacy. For example, the Library of Congress entry for Melvil Dewey lists only his whitewashed legacy of achievements and none of the abuse he inflicted on his colleagues. According to Wiegand, Dewey was "spared an ugly and public exposé" in exchange for a quiet departure — but nearly 90 years after his death, the silence is almost eerie.

"I think that it ought to be common knowledge," Sherre L. Harrington, coordinator of the ALA's Feminist Task Force, said in a statement to American Libraries Magazine. "But I don't think it actually is."