The Messed Up Truth About The Matchstick Women

It's no secret that there's a long history of employers treating their employees really, really badly. Long hours and low pay is just the tip of the iceberg, and it turns out that a deep dive into some olde-timey professions turns up some seriously disturbing stuff. While everyone knows, for example, that being a chimney sweep was a miserable, dirty job, there's more to it: Kids — and they were mostly kids climbing into those twisting, turning, Victorian-era chimneys — had a high likelihood of living a very short life, brought to an untimely end by something called "chimney-sweep cancer."

History is full of awful jobs with awful consequences. In the early 20th century, the so-called Radium Girls had seemingly fine jobs that everyone envied — particularly when they painted themselves with glow-in-the-dark paints. All was well and fine ... until it suddenly wasn't, and parts of their faces started rotting off.

Before the Radium Girls went to court to try to get some kind of compensation for the families who would survive them, there were the matchstick women. As the name suggests, these were women and girls who earned their living by making matches. It sounds harmless enough, but by the time many of them learned that what they were doing was deadly, it was too late.

It started with the invention of the friction match

For the whole story of the matchstick women, there's a little bit of background that's needed first — especially considering that today, it's nothing to strike a match (or flick a lighter) and make fire happen. It wasn't always that easy, though. For centuries, making fire was a pretty labor-intensive endeavor that, according to the Pitt Rivers Museum, required the use of flint and tinder. The idea of using a chemical reaction to kick-start a fire only really came about in the 17th century, and it wasn't until 1827 that John Walker accidentally invented something much, much better.

Walker had originally intended to become a surgeon, but it wasn't long into his study that he decided he wanted a life with considerably less blood in it. After opening his own chemist's shop in Stockton-on-Tees, he quickly realized that his background in chemistry and botanical studies gave him something of a unique perspective on things. In addition to making his own medicines (they were definitely different times), he also spent some of his spare time conducting various scientific experiments.

The breakthrough came when he was trying to develop a combustible paste. It would have been a big deal for the military, but when he scraped the stick he'd been using to stir his experimental paste with along his mantelpiece, he invented something that had a much wider appeal: the match.

Match-making became a massive industry

John Walker's "friction lights" were wildly popular, but here's where things started to go a little bit off the rails. Walker believed that everyone should have access to these easy-to-light fire sticks, so he didn't apply for a patent. That meant, of course, that everyone started making them, and he was run out of the business by the early 1830s (via Stockton-on-Tees). (He died almost penniless in 1859. Tees Valley Museums says that he was uncredited for the invention for decades, and it took 150 years for a statue to be erected in his town.)

Because Walker didn't patent his invention, other companies sprang up and started making matches by the literal boatload. Fast forward to 1860, and that's when the whole process turned deadly. Why? Because according to research done by the Bayonet Medical Center and the Beacon Head and Neck Clinic, it was around the 1860s that many of these large-scale matchstick factories added phosphorus to the previously sulfur-based paste that sticks were dipped into to make the matches. The phosphorus was added to give the matches a bigger, brighter flame, and while that's all great for the consumer, it created a massive problem on the manufacturing side.

When match-making grew to an industrial scale, giant vats of the phosphorus-based mixture were used for dipping. Those vats gave off toxic fumes, and within 3 to 5 years of first being exposed, workers would start to suffer catastrophic consequences.

What is phossy jaw?

The workstations of the matchstick girls usually consisted of a tray heated from beneath. Sticks of the phosphorus-based mixture were dissolved in water, then the matchsticks were dredged through. While they worked over the trays, the factory air would fill with the fumes given off — and those fumes were the cause of a condition called phossy jaw (pictured).

About 11% of matchstick women developed the condition, says the Smithsonian, and to say it's wildly unpleasant is an understatement. According to The Guardian, the easiest route for the phosphorus to take in its infiltration of the body was through the soft tissues of the mouth and jaw, and that's where most symptoms would start. The first hint that there was something wrong would be the toothaches, and it wouldn't be long before teeth would start falling out. Abscesses would start to form, and pus would leak from holes in the face so large and so deep that the dying bone of the jaw could be seen through it. Not bad enough? Phosphorus glows — that's how it got the name, which is Greek for "light bearer" — and if there was enough phosphorus in the body already, the exposed bones would glow.

In 1892, a reporter from a London newspaper called The Star visited a Mrs. Fleet, who had developed phossy jaw after working for a factory for five years. Her dying jawbone — visible through her cheek — smelled so horrific that her family could no longer be in the same room with her.

The case of Cornelia

The description of phossy jaw alone is awful, but let's make this personal and look at the case of a 16-year-old girl named Cornelia. James Rushmore Wood documented her case for the Royal College of Surgeons of England in the report "Removal of the entire lower jaw," and yes, he removed her lower jaw. Cornelia, he wrote, was an orphan girl who had been in perfectly fine health until she started working in a matchstick factory. After about six months in one factory, she moved to the packing department of another. It wasn't long before she complained of a toothache — the tooth was pulled, and everything seemed mostly all right.

Until, that is, "a spontaneous opening formed on the under side of the jaw, with a discharge of pus." A physical exam quickly determined that although she was otherwise completely healthy, she was suffering from the complete necrosis of the bone on the right side of the jaw. Wood decided to remove it to try to stop the death of the bone, so — as Cornelia sat on the operating table — Wood cut the piece of bone out of her face. That's terrifying enough, but anyone reading the report carefully will see this casual mention: "No anaesthetic was used."

Wood documented her daily treatment, and soon wrote that the condition was continuing to spread. It would lead to the removal of the rest of her jaw 28 days after the first operation, and shockingly, Cornelia went on to recover.

Workers labored in unthinkable conditions

Working conditions in the factories of the Victorian era were almost singularly awful, and according to the Smithsonian, that was absolutely true of the matchstick factories. There were hundreds of these large-scale matchstick production facilities at the height of the boom, and they were pretty much all on a scale that went from "awful" to "deadly."

The majority of matchstick makers were women, and specifically, they were mostly teenage and pre-teen girls. Crammed into claustrophobic rooms filled with vats releasing toxic fumes, they would work an average workday of between 12 and 16 hours. Need to grab a bite to eat? You'd better do it at your workstation, and do it fast. Don't mind the fumes and the phosphorus, and let's just add this little tidbit to make the mental image of a matchstick factory complete: Phosphorus, says the National Library of Medicine, has a very distinctive smell that could be described as being the worst-smelling garlic in the world.

As if that wasn't bad enough, they were under incredible pressure. SLS UK says that their pay — which was already low — was based on how many matches they made in each shift ... but there was a catch. They rarely took home what they had earned, because in addition to having to pay for their own supplies — like brushes — they were also regularly fined by their employers. Offenses included things like having a messy work area, talking to other workers, or dropping a match.

The matchstick women found a champion in Annie Besant

Annie Wood married Reverend Frank Besant when she was 19 years old. After he demanded she follow his religious beliefs, she happily accepted her excommunication, headed to London, and started her life's work. That really got going when she became a journalist for The National Reformer, says The Irish Emigration Museum. In addition to taking a very public stand for birth control, she also took on the cause of the matchstick women by publishing "White slavery in London."

The piece outlined just what a typical worker earned, starting with a weekly salary of 4 shillings. (For reference, Victorian Era notes there were 20 shillings (s) in a pound, and 12 pennies (d) in a shilling.) Her rent was typically about 2s, and she may or may not have made enough to cover it. Talking or even just having dirty feet could result in a fine of 3d, and if any matches were accidentally lit anywhere in the manufacturing or packing process, that was another fine. (Historic UK adds that an "unscheduled toilet break" would also incur a fine.) The end result was long hours, hard work, and a salary that wasn't even enough to allow them to buy food.

Besant wrote in condemnation of factory owners: "Oh if we had but a people's Dante, to make a special circle in the Inferno for those who live on this misery, and suck wealth out of the starvation of helpless girls."

The exposure of Bryant and May

There were hundreds of matchstick factories in the country, but Annie Besant's damning article on "White slavery in London" focused on one: Bryant and May. (It's worth noting that the company is unrelated to the present-day Bryant and May.) It didn't go over well.

Besant's initial article was published on June 23, 1888, and the following weeks, she provided updates: Employees were being bullied in an attempt to learn who had spoken to the press about the factory's working conditions. Several were ultimately fired, and Besant started a campaign to compensate the workers for the income — and employment — lost in the uproar. Not only did people donate, but other publications started picking up on the story. Government inspectors got involved, and while they put an end to the system of fines, there were still the unsafe working conditions to deal with.

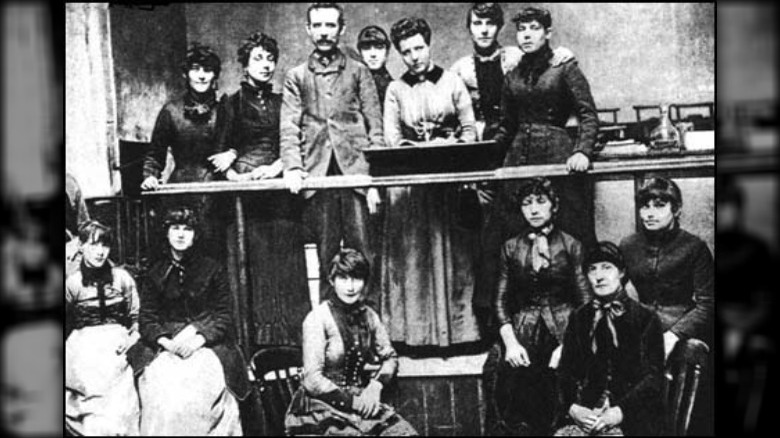

Even as Besant put out a public appeal to only buy matches from companies that paid a decent wage, Bryant and May tried to do some damage control. According to Catherine Best, lecturer in the School of Nursing and Healthcare Leadership at the University of Bradford (via The Conversation), that's about when Bryant and May tried to force their employees to sign a document stating that they were perfectly content with the conditions at the factory. Sounds shady? The employees thought so, too, so they walked out on strike — all 1,400 of them.

The strike that paved the way for employee rights

The story of the matchstick women going up against Bryant and May is a little like the story of David and Goliath. The women were, says The Guardian, mostly uneducated, poor, Irish immigrants, while the company was one of the largest in London, with connections to some of the most powerful people in the city, and beloved by everyone who didn't have to work there.

Still, change happened — and it happened on a grand scale. Women took to the street to protest, and supporters not only joined them in solidarity, but gave donations that helped replace the wages they were losing. When they headed to Parliament, the government had little choice but to listen.

Historic UK says that the strike came to an end within a matter of weeks, and the matchstick women had won a sweeping victory not only for themselves, but for all employees. Not only had they proven that David can, indeed, take down Goliath, they also won the right to form a trade union that would settle future disputes and oversee the shift into better pay and safer working conditions. The Union of Women Matchworkers became the blueprint that would inspire the organization of workers in opposition to unfair working conditions, and it didn't take long: The following year, London's dockworkers organized in protest when they were bid: "Stand shoulder-to-shoulder. Remember the match women, who won their fight and formed a union."

The Salvation Army stepped in

Part of Annie Besant's appeal in "White slavery in London" was to ask the public to pay attention to where they were buying their matches from. She asked that they only buy from ethical organizations who paid employees for their labor, and here's where The Salvation Army stepped in.

In 1891, they opened their "Darkest England" Match Factory, and it was meant to be an invaluable addition to their social justice campaigns. They had already been addressing issues like homelessness and hunger, and workers' rights were right up their alley. The idea was that they were going to pay their workers well and run a safe factory free of the deadly phosphorus fumes. At the same time they advertised their socially responsible matches, they also lauded the benefits of buying local and putting local people to work.

To be fair, it was a pretty good platform to stand on. According to an 1892 article in the Woman's Herald (via the White Ribbon Association), the Salvation Army's factory was clean and fume-free, and workers were getting 16s per week — four times the wages of a Bryant and May worker (before fines were imposed). While a decent salary is a must-have, the business model ultimately didn't work. The necessity of selling the matches for a higher price meant that many people went elsewhere for their match-buying needs, and the Salvation Army's match factory closed in 1894.

Phossy jaw has made a comeback

Technology is always being improved, and that applies to things like matches, too. Alternate formulas were developed, and even though white phosphorus matches had all the qualities a consumer wanted in a really good match, the plight of the matchstick women encouraged alternate formulas.

According to Britannica, one was actually developed in 1864, but in typical fashion, it wasn't popularized until 1898. Phosphorus was outlawed soon after, and Colgate says that by 1906, the concoction that produced the deadly fumes had been replaced completely. That meant the end of phossy jaw — which, they add, was also called osteonecrosis. Good news, right? Not so fast — because they further add that it's back.

That's right: Now, in the 21st century, people are once again developing phossy jaw, and here's why. There are multiple medications that have been developed fairly recently, and they contain bisphosphonates. Johns Hopkins says they're used in the treatment of things like lupus and osteoporosis, which are both conditions that weaken the body's bones. While the medications help counteract it, a possible side effect is phossy jaw. Sure, it's rare, but non-existent would be even better when we're talking about a condition where your bones start to die and rot through your skin.