Common Misconceptions About The Victorian Era

Those living during the Victorian era witnessed massive transformations in the United Kingdom and its overseas empire, according to the Royal Museums Greenwich. Spanning 63 years, the reign of Queen Victoria ranked the longest in British history up to that point and has only been surpassed in the 21st century by Queen Elizabeth II (via Reuters). Victoria first took the throne in 1837 and remained the nation's figurehead until her passing at the age of 81 in 1901.

During her reign, she helmed the British Empire's transformation from a rural collection of isles into the first industrial superpower, with financial and political influences spanning the Earth's four corners. Her kingdom single-handedly manufactured most of the globe's textiles, steel, iron, and coal. Besides its role as an economic behemoth, the kingdom also made significant advances in the sciences and arts.

No wonder there's still so much fascination with this dynamic period. But, of course, any era that captures the public's imagination also comes with the baggage of common misconceptions. That said, some of these prove so contradictory it's hard to wrap your head around them. For example, legend has long held that Queen Victoria's spouse, Prince Albert, had a ... well, you know ... "Prince Albert" (via the Huffington Post). Yet, history also judged the couple sexual prudes along with the whole realm, per The Guardian. As they say, truth is stranger than fiction. So, get ready for your head to spin as we explore the strange world of Victorian misconceptions.

Victorians didn't love their children

Many people look back and assume that children in the Victorian era led inconsequential or downright impoverished existences, and with good reason. Grimy, school-aged chimney sweeps and miners weren't uncommon among members of the working class, according to The Guardian. Victorian authors, like Charles Kingsley and Charles Dickens, populated their novels with orphans, mudlarks, guttersnipes, and street urchins, reflecting an unpalatable reality present from the seediest parts of London to the textile mills of the rural North, per the Victorian Web.

"Dumbledore in the Watchtower: 'Harry Potter' as Neo-Victorian Narrative" speculates that these grim and commonplace representations stemmed from "the anxiety Victorians felt when trying to cope with the large number of orphans and street children in their own time" (via Cambridge Scholars). In other words, the presence of these characters in literature attests to an increasing concern for children of all classes and backgrounds.

According to "Perceptions of Childhood" by Kimberley Reynolds, many Victorians came to romanticize childhood, perceiving it as a time of innocence and freedom worth protecting. Their views collided with those of industrialists who exploited kids for cheap labor. But these romantic ideas saw expression in a growing body of children's literature, as reported by M. O. Grenby's "The Origins of Children's Literature." This explosion of children's literature bore witness to changing British ideas about the sacred nature of childhood.

No diversity existed in Victorian Britain

History Today tells a little-known history of diversity that exists in the British Isles. The Romans staffed outposts and forts with troops from all over the empire, including Africa. And the "Annals of Ireland" from 862 A.D. discuss Vikings coming ashore in Ireland with enslaved Black people taken from North Africa and Spain. In Norfolk, England, a 10th-century burial revealed the skull of a young Black woman, and by 1500, a community of Blacks existed at Scotland's Royal Court at Holyrood.

By 1764, 20,000 Black servants lived and worked in London. And in 1838, Great Britain abolished slavery across the Empire, per the National Archives. Victorian Britain was more diverse than often portrayed in popular culture (via The Equiano Centre). Identifying the ethnicities of individuals living in various regions of the country isn't the easiest task since historical documents didn't always note ethnicity, per The Guardian. But historical portraits are aiding this research.

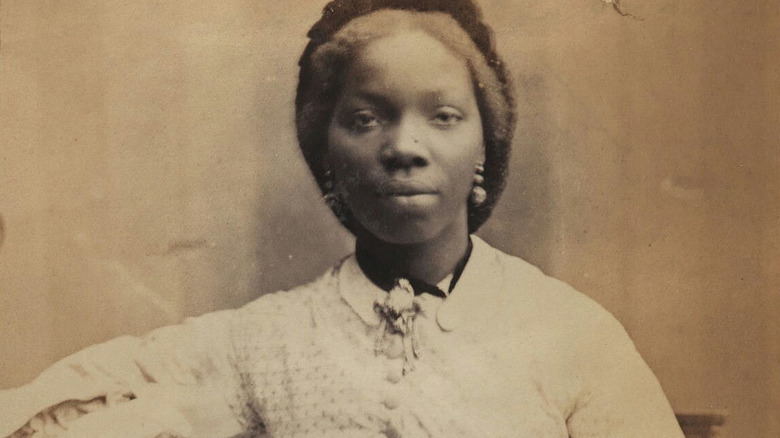

The Guardian reported in 2020 on the release of a new portrait of Queen Victoria's adopted African goddaughter. Christened Aina, she took the name Sarah Forbes Bonetta after her adoption by the British Royal Court. Bonetta came from West African royalty but faced enslavement in Benin by her father's enemy. A British naval captain, Frederick Forbes, rescued the little girl, presenting her to Queen Victoria upon his return. She sailed to England on a ship named the "HMS Bonetta," commemorated in her chosen name.

Victorians followed the prudish example of their queen

Queen Victoria and her subjects have gotten a bad rap as sexually frigid (via The Sydney Morning Herald). But primary sources tell a different story. Queen Victoria enjoyed a steamy romance with hubby Prince Albert. Get a load of how she described her wedding night: "I NEVER, NEVER spent such an evening! ... He clasped me in his arms, and we kissed each other again and again! His beauty, his sweetness and gentleness, — really how can I ever be thankful enough to have such a Husband!" No wonder the marriage produced nine children.

During their 20-year marriage, they also exchanged erotic gifts, according to The Guardian. It resulted in a bevy of collected works at Osborne House, a coastal retreat on the Isle of Wight. And Victoria and Albert weren't alone in celebrating the sensual, per The Guardian. Yes, some among the middle class cultivated a prudish type of puritanism that applied mostly to women. But feminists like Thomas Hardy fought against such hypocrisy, giving women new voices and sensuality, per a 2020 article published in the International Journal of Applied Linguistics & English Literature.

And you don't have to dig deep to find the sexy side of Victorians. Music halls ruled entertainment, featuring flirtatious songs and raunchy comedy. Victoria and Albert were far from the only collectors of nude artwork. Courtesans mixed with high society, and brothels thrived just outside of the watchful eye of the public.

Victorian men sported 'Prince Alberts'

Since the mid-20th century, a rumor has circulated that Albert had a genital piercing, used to tuck and pin his package in tight trousers. In "Body and Genital Piercing in Brief," Doug Malloy claims Victorians referred to this "device" as a "dressing ring," and it served more than one purpose in Prince Albert's case.

Besides reigning in the royal jewels, Malloy claims the "dressing ring" improved the Prince's uncircumcised hygiene. While Malloy also discusses the pleasure element, he doesn't tie it directly to the Prince's piercing decision. But as "Different Loving: The World of Sexual Dominance and Submission" explains, the historical evidence supporting "dressing rings" doesn't exist. What's more, Matt Loder of the University of Essex, casts doubt on Malloy's credibility: "[He] created a lot of pseudo-historical tales about the origins of various piercings back in the 1960s and 1970s" (via MEL Magazine).

Despite a lack of evidence, the rumor has persisted into the present, perpetuated in works like Kurt Caswell's "An Inside Passage." And the pernicious use of the Prince Consort's name in association with the piercing has made it virtually off-limits when it comes to naming future generations, per Metro. After all, who wants to name their kid after a "penile piercing"? To be fair, some say "dressing rings" got started with Beau Brummel, and since he lived in the Victorian era, Prince Albert became guilty by association. But the verdict's still out on this.

Victorians were a humorless lot

Brits living in Victorian times have a dour reputation. Yet, the Victoria and Albert Museum claims they were actually a good-humored lot. They loved bawdy entertainment meted out in taverns, supper rooms, and saloons. Although respectable women avoided these establishments, all members of working-class families attended. Among the most famous early music halls was London's The Eagle, which attracted the thronging masses for musical shows involving tongue-in-cheek humor.

According to Illustration Chronicles, we can't forget about the impact of satirical publications such as Punch Magazine. This journal enjoyed a solid run from 1841 to 2002, publishing articles by notable authors from William Thackeray to P.G. Wodehouse. It attracted a robust middle-class readership by showcasing political debate mixed with a hefty dose of humor. Soon, satirical political cartoons filled its pages, taking hints from Parisian weeklies like Le Charivari. Besides Punch Magazine, publications known as "manuals of table-talk" also demonstrate Victorian wit (via The Conversation).

Although Victorians enjoyed their music halls and satirical magazines, they also sat for what some might call depressing photos, as Time points out. But the lack of smiles doesn't reflect on their personalities or humors. Instead, it had everything to do with poor dental care combined with the unpleasant nature of sitting for a photo. The Christian Science Monitor reports that subjects had to hold perfectly still for a quarter of an hour to complete the exposure time for a daguerreotype. We challenge anyone to try smiling for that long!

Victorian women suffered in corset torture devices

Many people today equate Victorian corsets with medieval torture machines. But this well-structured undergarment wasn't the iron maiden of Britain's foremothers, as reported by Foster's Daily Democrat. Sure, some individuals took corset-wearing to extremes, injuring themselves in the process. But the same goes for skinny jeans, as reported by National Public Radio (NPR).

Costumer Astrida Schaeffer argues that well-fitting corsets didn't cause women discomfort. She explains, "If it hurts, it's not fitted properly. Corsets are not meant to be instruments of torture" (via Foster's Daily Democrat). She also debunks the claim that corsets shrank a woman's waist to unnatural proportions. Instead, they reduced waists by an inch or two, kind of like 20th-century shapewear (via the Times Union). In other words, Victorian undergarments created clean contours, not freakish figures.

To create the illusion of whittled middles Victorian garment designers had many innovative techniques in their bag of tricks. These included blousy, full sleeves, making waists appear more diminutive. What's more, children and men even wore corsets in some cases. And as for the notion that women required multiple servants to help them get into their underwear, that's a load of malarkey, too. Women had no trouble getting into and out of their undergarments, as reported by Lancaster History. Arguably, these facts take some of the fun out of bodice rippers. But they do present a more empowered picture of the women who laced themselves.

Victorian women removed ribs for waspier waists

Another longstanding myth says some Victorian women underwent rib removal surgery to achieve an hourglass figure (via "The Berg Companion to Fashion"). But according to Lancaster History, such ideas are "entirely mythical" (quoting "The Corset: A Cultural History"). Put another way, this urban legend has more to do with our misperceptions of corsetry and Victorian fashion and less to do with anything that actually happened.

Victorian corsets molded waists in the 24- to 30-inch range. Some women today fall within this range, no shapewear needed. While corset outliers existed, measuring little more than 18 or 19 inches, they don't represent the standard. Some costume historians believe the mythology surrounding Victorian garments stems from misunderstandings about proper wear. For example, women left a two- to three-inch lacing gap when cinching up their corsets. Yet, many people today mistakenly assume they tightened them until they were gapless.

What's more, surgery to have ribs removed represented an unfathomable risk (and pain!) in an era without anesthesia and antibiotics, as reported by The Atlantic. Surgeons wore street clothes and didn't understand the need to wash their grimy hands. Blood-encrusted aprons represented "badges of honor" physicians never laundered, and they performed grisly procedures in rooms filled with spectators. Victorian-era surgeon Joseph Lister referred to his specialty as the "bloody and butcherly department of the healing art." So, voluntary cosmetic surgery wasn't a thing in 19th-century Great Britain.

They invented (and used) fainting couches

With so many Victorian undergarment myths debunked, you may have started doubting accounts of women laid out on fainting couches due to corset-induced hyperventilation. And your hunch is correct. While movies and pop culture tend to focus on the rigidness of corsets, this doesn't paint an entirely accurate picture, as reported by Lancaster History.

In reality, corsets contained enough flexibility to permit largely unrestricted breathing. After all, Victorian women, especially working-class ladies, led active lives. And they laced their corsets accordingly. If they finished cinching up and couldn't catch their breath, this was a sign the garment fit poorly, or they had overtightened it. The obvious solution was loosening the laces — a simple and easy fix.

As for the term "fainting couch," it represents a modern invention, as attested by this Google Ngram. If you're not familiar with Ngrams, they search material printed over the years for instances of a given term. In the case of "fainting couch," the phrase didn't show up in the printed word until around 1970, skyrocketing in use from there. Ironically, what we think of as fainting couches today, Victorians called day beds. Rather than necessary remedies for regular unconsciousness, these luxurious pieces of furniture invited women and men to get off their feet. What's more, these pieces of furniture boasted millennia of popularity, copied from ancient Greco-Roman pieces.

Queen Victoria was the first bride to wear white

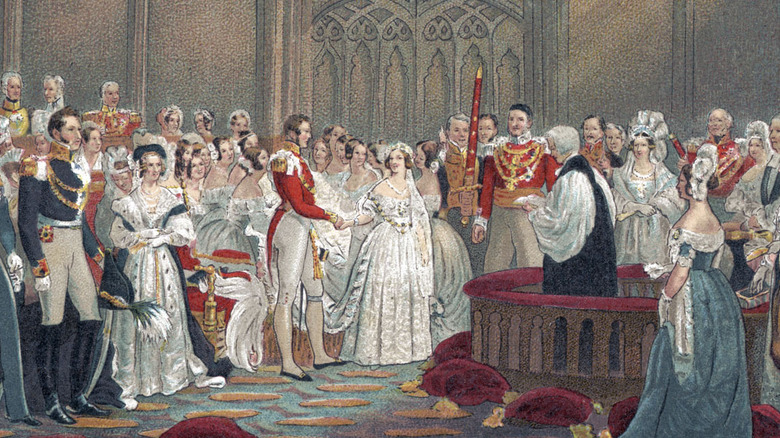

Many people think Queen Victoria was the first bride to wear white, and we do have to give her props for making it an almost mandatory part of bride-dom, per Vanity Fair. But while Victoria had a significant hand in making white the most popular bridal color in the Western world, the trend had predecessors within the British royal family.

For example, Princess Charlotte wore the hue more than 20 years earlier, on May 2, 1816 (via Royal Central). Today, the dress remains preserved in Kensington Palace's Royal Ceremonial Dress Collection, and historical sources tell us she accessorized with earrings, pearls, (maybe) an armlet, and a diamond wreath. But according to CNN, even Charlotte didn't have a premium on white. That honor goes to the 16th-century trendsetter Mary Stuart, Queen of Scots.

According to historical records, Stuart, 15, wore white during her nuptials to the Dauphin of France, 14, in 1558. She looked so fierce sporting the color with a diamond necklace and jewel-studded gold crown, that Pierre de Brantôme declared her "a hundred times more beautiful than a goddess of heaven ... her person alone ... worth a kingdom," per History Today. Yet, despite the flattery, white wouldn't catch on until Victoria. Ironically, many people assume Victoria chose the color to emphasize her sexual purity. But it had more to do with showing off to best advantage the handmade lace commissioned for the big day.

Vibrators were invented to relieve 'hysterical' women

Plenty of hype in recent years surrounds the alleged medical treatment prescribed for Victorian women diagnosed with "hysteria" (via The Atlantic). As the myth goes, doctors treated "hysteria" by manually manipulating female orgasms (a.k.a. "hysterical paroxysms"). Out of practicality, they invented vibrators, which proved "less fatiguing" for physicians. This anecdote can be traced to 1999's "The Technology of Orgasm: 'Hysteria,' and Women's Sexual Satisfaction" by Rachel Maines.

But as The New York Times maintains, just about everything we think is true about the invention of vibrators isn't. According to the BBC, the first electric vibrators were advertised in the 1800s to medical doctors via periodicals, medical literature, magazines, and newspapers. Advertisements show them used to massage tense necks, backs, and arms. But there are no sexual implications in this early content.

What's more, images depict both men and women gaining relief from these devices. As one flyer notes, "By this method 50 per cent of the fatigue to masseuses, inseparable from the usual manual massage, is avoided. Infinitely better results in treatment are obtained." As these texts and images prove, vibrators treated various ailments as a potential cure. That's not to say that some naughty Victorian minxes didn't experiment with them once mass marketing to the public began after 1900. But that's a story for another day.

Victorians covered piano legs to avoid sexual suggestion

In 1839, a British captain named Frederick Marryat published a travelogue about his experiences in the United States, as reported by Atlas Obscura. In one entertaining passage, he launched a legend about Victorian prudishness that lingers today.

While visiting a seminary for young women, he noted with astonishment that even the legs of a piano at the institution had to be covered to avoid sexual associations. Speaking of the care that the headmistress of the school put into protecting the innocence of her charges, he wrote, "She had dressed all these four limbs in modest little trousers, with frills at the bottom of them!"

This urban myth has persisted for more than a century. But contemporary scholars like Therese Oneill take this tale with a grain of salt. In her book "Unmentionable: The Victorian Lady's Guide to Sex, Marriage, and Manners," she calls the notion of covering furniture legs to maintain sexual purity an utter fabrication (via Atlas Obscura). As it turns out, covering furniture legs happened for a much more practical reason. It permitted furniture and piano-owners to protect their investments from scuff marks, scratches, and normal wear and tear.

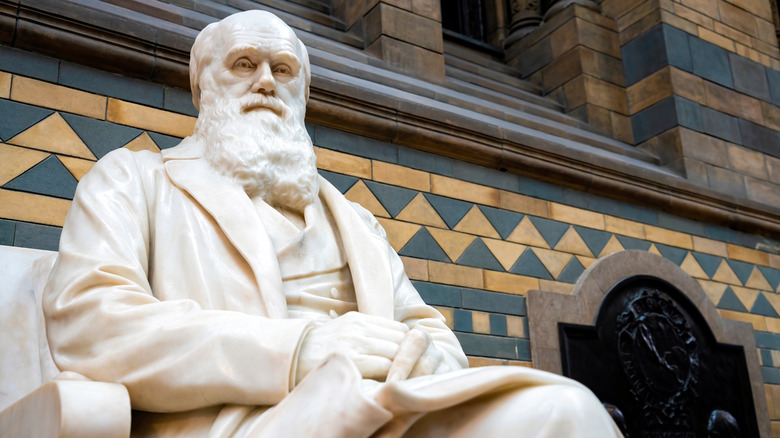

Charles Darwin shocked Victorians with his theory of evolution

When people hear "evolution," many think of the Victorian researcher Charles Darwin. While he articulated "natural selection" as the process by which evolution occurred, the theory of evolution predates Darwin by a couple of generations, as pointed out by the National Park Service.

The concept of evolution first gained recognition with Darwin's predecessors like Jean-Baptist Lamarck, Robert Chambers, and Erasmus Darwin (Charles Darwin's grandfather). Lamarck came up with the idea that "acquired characters are inheritable," according to Britannica. And Robert Chambers anonymously authored "Vestiges," which explored the concept of evolution harmonizing theories from the fields of geology, comparative anatomy, psychology, and astronomy (via the Victorian Web).

As for Erasmus Darwin, he wrote the work "Zoonomia, or, The Laws of Organic Life," considered one of the earliest books to flesh out the theory, per the University of California Museum of Paleontology. That said, Charles Darwin deserves credit for disseminating the theory widely and added his own unique touches like "natural selection."