What Really Happened During The Kazakh Catastrophe?

Just as the Holodomor, or the Great Famine of Ukraine, was beginning in 1932, another famine in the Soviet Union was already well underway. The Kazakh famine of 1931 to 1933, also known as the Asharshylyk and Zulmat, or the Kazakh Catastrophe, led to the deaths of millions of Kazakh people. The Wilson Center calls it "one of the worst catastrophes in human history." Kazakh researchers also refer to the famine as "Goloshchekin's Genocide," (per SciencesPo), due to the fact that Filipp Goloshchyokin, First Secretary of the Kazakh Regional Committee, was integral to the Sovietization of Kazakhstan and was directly responsible for underreporting mortality during the famine.

After the Kazakh Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic was established in 1920, the people of Kazakhstan were subjected to Sovietization. And although these policies ramped up especially during the implementation of the Five Year Plan in 1928, which led to the most agricultural collectivization, it's estimated that over 1 million people died "during the starvation of 1921-1922" alone, according to an article in Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences, posted at Science Direct.

The famine of 1931 to 1933 is also unique due to its man-made qualities. Although there were some environmental factors at play, the famine was largely caused by the Soviet destruction of Kazakh pastoral nomadic life. Many historians argue whether or not the famine was intended as a genocide, but even if the famine was the result of deliberate intent, little was done to prevent its effects.

'Debajization'

Debajization was the Soviet Union's effort to end the "hierarchies in [Kazakh] nomad society." This was coupled with "the destruction of the tribal solidarity that prevented the state from controlling socio-economic relationships in rural areas." In "Famine in the steppe," published in Cahiers du Monde Russe (posted at Open Edition Journals), Niccolò Pianciola writes that nomadic mobile villages, or auls, were composed of wealthy members, known as the bai, who would essentially allow their livestock to be taken care of by more financially insecure members. While the livestock remained the property of the wealthy aul member, "all the produce [the renter] was able to obtain from [the livestock] (milk, other dairy products, wool) was his and in this way subsistence was guaranteed."

According to "The Kazakh Famine" by Isabelle Ohayon (posted at SciencesPo), debajization involved confiscating the livestock from the bai as well as deporting the bai. Between 1929 and 1933, the number of livestock in Kazakh nomadic farmers' herds dropped from over 40 million to less than 5 million (per Global Voices).

Pianciola describes this "expropriation of the property" as a cover for the "indiscriminate pillaging of the rural Kazak population." Soviet party members would sometimes confiscate livestock just for themselves.

The drop in livestock was also caused by a high mortality rate, since large numbers of animals were kept concentrated together without enough resources to take care of them, and epidemic illnesses often spread. However, the administration took "no measures to save them." This was also exacerbated by the 1927-1928 džut, a period of extreme cold in which many livestock died.

Collectivization and sedentarization

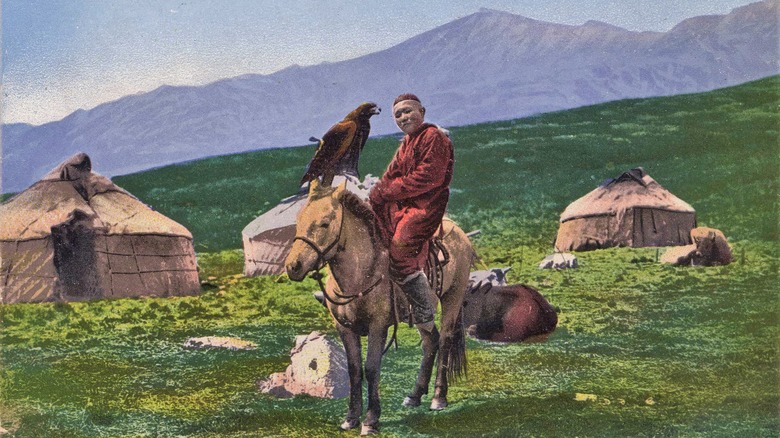

In the late 1920s, over 75% of Kazakh people were "nomadic or semi-nomadic" and their economy and sustenance was based around their livestock. Although many people also farmed, according to "Famine in the Steppe," "in the majority of cases it was a secondary and accessory activity compared to that of keeping animals" and typically the most financially insecure people were involved primarily in agriculture. However, with the confiscation of animals, most Kazakh people were left without livestock.

Collectivization also involved the imposition of grain crop requisitions. And "the districts where procurement obligations [were] proportionately most oppressive were the ones heavily inhabited by nomadic herdsmen, for example the Karkaralinsk district," according to "Famine in the Steppe." In The Kazakh Famine, Isabelle Ohayon writes the grain requisitions during 1929 to 1932 represented roughly 33% of the Kazakh ASSR's total grain production.

Taxation and fines were also used by the Soviet Union "to funnel large numbers of animals towards the state and the non-nomad sector of the population." As a result, many people were forced to work on kolkhozes, or collective farms, as well as sovkhozes, or state-owned farms. With this, "sedentary farming activities" were imposed onto the Kazakh population. Meanwhile, all of the farm's produce was "taken by the government as compulsory supplies of cattle and grain," writes the Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities.

These farms and forced sedentarization, part of the Five Year Plan, became "a central element in a cluster of measures taken to control and repress nomadic Kazakh society."

The Kazakh Catastrophe

Coupled with several severe droughts and "high cattle mortality," all of these factors combined to create a humanitarian crisis in Kazakhstan in the early 1930s. The Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities writes that by February 1932, "87% of collective farms and 51.7% of individual farmers had totally lost their livestock." Without livestock, Kazakh people lost access to their traditional diet, which consisted mainly of milk-products and meat.

Pianciola writes in "Famine in the Steppe" that in some districts, people ended up eating cats, dogs, and carrion in order to survive. "Cannibalism [also] became widespread." The famine lasted from the winter of 1931 to winter 1933 and was "equally tragic throughout Kazak[h]stan." By the spring of 1932, Europeans in Kazakhstan were also affected by the famine. By the spring of 1932, over 100,000 people fled Kazakhstan, headed towards China, Siberia, the Northern Caucasus, or Ukraine. Tens of thousands of children were abandoned by families who couldn't feed them, amounting to over 60,000 by 1933, but they were "crowded into orphanages" and often died of hunger there.

Denied aid

Not only did the Soviet Union have a delayed response to the famine, but when they finally sent aid, it was sorely inadequate. According to the ABAI Center, after the famine was already well underway, "Moscow delayed sending aid," partially because they believed that hunger and famine were simply the result of the Kazakh peoples' nomadic lifestyle, and partly because "officials were influenced by another stereotype, that nomads possessed immense numbers of animals."

When aid finally came in the form of grain, it wasn't enough. In one sovkhoz, a family received less than 200 pounds of bread a year, "far from meeting the minimum basic need," according to "Famine in the Steppe." In the Alma-Ata oblast (administrative district) alone, over 22,000 families were left "completely without grain."

There were two main forms of aid: food aid, which didn't need to be repaid, and seed aid, which was meant to be a loan that was to be repaid with interest. Although the seed loans would reach the Kazakh population, most of the food aid never reached its intended starving recipients. In January 1933, a report claimed that "the theft of grain along the route has reached enormous proportions." But no one was ever formally charged with stealing the grain. In the event that the food aid did reach the Kazakh population, it was often "sold rather than distributed" freely.

Losing half the population

Nobody knows exactly how many people died during the Kazakh famine. Estimates range from 1 million to over 2 million people (per Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences) with some estimating that up to half of the Kazakh people died as a result of the famine, if not more. Up to 250,000 non-Kazakh people also are believed to have died due to the famine. The Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities writes that the total number of people affected by the famine, including refugees who fled, may be as high as 5 million. Although it's unclear exactly how many lives are lost and how many people were affected, "all that is certain is that entire zones were emptying of their inhabitants," according to "Famine in the Steppe."

In addition to the millions that died from the famine itself, thousands were also killed by Soviet border guards, "who were given orders to shoot refugees for illegally crossing the Soviet-Chinese border," Nazira Nurtazina writes in Great Famine of 1931-1933 in Kazakhstan. Kazakh people fled from the famine to China, Mongolia, Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey. An unknown number also died from starvation and epidemics during the "tragic exodus."

Legacy of the famine

Ultimately, the nomadic lifestyle of the Kazakh people never recovered after the forced sedentarization and the famine. There was no livestock with which to resume their pastoral nomadism, so there was little choice (per the Abai Center) other than to stay on the farms. Meanwhile, "there was an eerie silence in the steppe" that was once filled with the sound of bleating livestock.

Voices on Central Asia writes that through the loss of the system of pastoral nomadism, "a new Kazakh national identity" was created. This also likely came out of the fact that the death rate was highest among the elders, who were "the traditional bearers of collective memory," which was sustained through oral history, as Ohayon writes in The Kazakh Famine.

The Kazakh people suddenly became a minority in Kazakhstan, and as forced labor camps were built in Central Kazakhstan for exiled people and deportees were brought in by the hundreds of thousands, Kazakh people wouldn't make up more than 50% of Kazakhstan "until after the Soviet collapse." With at least half of the indigenous population of Kazakhstan decimated, it took almost half a century for the Kazakh population just to recover to its previous numbers. Global Voices reports that the famine was "a demographic disaster that reverberates to this day."