The Untold Truth Of The 1923 Ku Klux Klan Trials

Though it's thought that hate groups like the KKK are a problem today, the hold that they once had on nearly every aspect of life in some communities is staggering. The terrorist group was formed as a reaction to the Reconstruction era that the Union introduced to the conquered Confederate States following the United States Civil War. Beginning the year the war was over in 1865, the KKK quickly grew to a presence in nearly every southern state within five years. History tells us that the KKK surfaced as a counteracting force to the Republican Party's Reconstruction-era policies, which focused on "establishing political and economic equality for Black Americans."

The KKK used fear and intimidation tactics to suppress voter turnout and were instrumental in the passage of southern Jim Crow laws. But with membership declining after the Reconstruction era, this hate organization was nearly defunct. It would take a film released in 1915 and a growing sense of nationalism among some white Americans to get it revived again some years later. Soon, the Klan would grow to control state legislatures in the south and countless city and county governments by the early 1920s.

With no end of their growing power in sight, it took a white man becoming the victim of Klan brutality in Texas to push one county prosecutor to press charges against an organization that so many of the era lived in fear of.

The second incarnation of the KKK was a powerful one

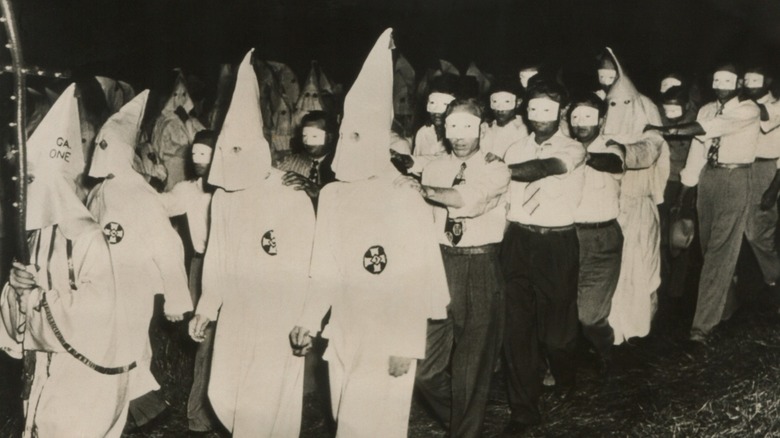

In order to fully understand the grasp that the KKK had on the state of Texas during the early 1920s, it's important to know just how large this organization was at this time. Nationally, the KKK reached its peak during the 1920s, with just over four million members. With this second incarnation of this hate group, it wasn't just small-town working-class folks that made up its membership — citizens from professional classes like doctors and lawyers were joining, giving an unsettling level of credence to the organization.

After having all but been eliminated following Reconstruction, the Klan emerged as a powerful political force following the release of D.W. Griffith's 1915 film "Birth of a Nation," which glorified the acts committed by the Klan following the U.S. Civil War. This got the attention of one William Joseph Simmons, who reorganized and successfully grew the next generation of the KKK into its peak a decade later. According to PBS, this newly revived organization took aim not just at Black Americans but also Catholics, Jews, and foreigners using a concoction of white supremacy and patriotism.

With the number of Klansmen rapidly growing, it's no wonder that Texas saw record-breaking Klan memberships. The Texas State Historical Association claims that KKK memberships in its state were as high as 150,000 in 1923. With so much support across the region, it's no wonder that many communities were under Klan control, and a good number of officeholders were members.

Klan control of Texas

The Klan was in control of a large part of Texas, and that control was growing rapidly. And it wasn't just in the small towns and rural areas that felt the presence of the KKK. According to WBUR public radio, in Dallas, one out of every three eligible men were KKK members. This large city was quickly becoming central in the Klan's control of the state.

"The KKK ran Dallas, and it became the epicenter of the movement," says Michael Phillips, a historian at Collin College, noting that the city's rise into such a focal point was inevitable. He said that Texas was a state beset by an "extraordinary level of racist violence," referring to the nearly 350 African American males who were lynched in the state between 1880 and 1930. With numbers swelling in Dallas and elsewhere in Texas, it's no wonder that the Klan had successfully infiltrated political offices.

These office holders ranged from local sheriffs like Dallas' Dan Harston and Travis County's W.D. Miller to one member elected to federal office (via Three Minutes of History). In the eastern two-thirds of the state, the Klan controlled most courthouses and city halls. In the early 1920s, the Klan even held a majority of the state legislature. And at the top of the elected food chain for the Klan was U.S. Senator Earle Bradford Mayfield, who was elected from the state of Texas in 1922 (per the Texas State Historical Association). But one court case started to take them down.

The first successful prosecution of a KKK member

With this much control, one can imagine how easy the Klan had it in Texas. They were free to wage acts of terror against anyone they felt was a threat to their way of life without any consequence to the organization. That all changed in late 1923, thanks to an event in Williamson County.

One elected official was having none of it. Williamson County Prosecutor Dan Moody was handed a case in which a white traveling salesman was kidnapped on Easter Sunday in 1923. The victim, Robert Burleson, was flogged and tarred after he refused a Klan order to leave town (via Williamson County Texas History). Moody launched a grand jury investigation, resulting in multiple local members of the Klan being charged. This resulted in a series of trials that were carried out against Klan defendants between September 1923 and February 1924.

The first man tried was Klan member Murray Jackson. Feeling that he had the strongest case against Jackson, Moody argued a court case that lasted seven days. At the end of oral arguments, the jury deliberated for only 20 minutes before rending a guilty verdict (per Williamson County History). Jackson was sentenced to the maximum and given five years in state prison.

This guilty conviction led to the trials of additional members of the Klan thought to be perpetrators in Burleson's kidnapping and torture.

The guilty convictions begin to pile up

Soon after, Dan Moody used the outcome of the Murray Jackson trial to successfully prosecute four more members, getting four more prison sentences (via Williamson County Texas History). According to Three Minute History, Moody then went back to the grand jury and was able to convince them to indict Klan leader A.A. Davis on perjury charges. When Moody asked Davis if he had ordered the warning to Burleson, Davis flatly denied doing so. But members of his local Klan chapter disagreed with Davis and his version of events. With their testimony, Moody was able to secure a guilty verdict on a perjury charge against Davis after a lengthy trial. The Klan leader was sentenced to two years in state prison for the offense.

These trials marked the first time the KKK was able to be brought into a court of law and successfully tried for their offenses. They also mark a point in history in which the Klan, though large in number and quite influential, saw its power quickly wane. Klan opponents saw promise in getting rid of the stranglehold the local Klans had on their way of life, and the KKK saw their political control quickly slip away in Texas. Other states took note and began to give the Klan the same reception.

A historical marker commemorates the trials

In 2009, the Texas Historical Commission erected a historical marker commemorating the successful prosecution of the KKK in Harrison County. Part of the inscription reads that the trials were "considered the first prosecutorial success in the United States against members of the 1920s Klan and quickly weakened the Klan's political influence in Texas." The marker is located in the county seat of Harrison County in the city of Georgetown. Located on the corner of South Main Street and West 8th, it stands next to a life-size statue of Dan Moody himself, the man who signified the beginning of the end of the Klan's political power (per the Historical Marker Database).

Moody was able to use the outcomes of these trials to vault into quite a political career. He successfully ran for the Texas State Attorney General's office in 1924 before getting elected to the office of Texas Governor in 1926; he was re-elected Governor in 1928. Moody was the youngest Texan ever to be elected to either of these offices (via Williamson County Historical Commission).