The Most Incredible Things Discovered In Caves

This wide, wonderful, weird world called Earth is filled with all kinds of ridiculously cool things: All it takes is a healthy curiosity about the world around us, and there's no limit to the number of things out there waiting to be discovered.

When it comes to the planet's landscape, there's one thing that's undeniable: Caves are cool. It's impossible to see a cave and not wonder what's inside, because even though the answer is usually something like "rocks" and possibly "bears," there's something about these things that just capture the imagination. There's good reason for that, too — sometimes, there have been incredible, unbelievable things discovered in caves.

Sometimes, that includes finding things like more caves. In 2021, the Cave Research Foundation announced (via the National Park Service) that they had found more miles of tunnels that were a part of the Mammoth Cave National Park. It was already the longest cave in the world, and with the newly discovered tunnels, it hit a length of 420 miles. For some perspective, that means driving the length of the caves would be like driving from New York City to Norfolk, Virginia. That's pretty wild, but when it comes to the most incredible finds in the history of caving, that's not even scratching the surface.

The world's oldest winery

The Areni Cave Complex — also called Trchuneri, or the Birds' Cave — is located in what's now Armenia, and according to World History, it's believed to have been inhabited as far back as 6000 BC. Archeologists have recovered scores of artifacts from the on-again, off-again history of human habitation, and among the discoveries they've made is what's currently the oldest winery in the world.

In 2011, National Geographic reported archeologists — including a team from the University of California — had finished excavating a site that had first been discovered in 2007. It included a wine press, vessels for fermenting, storing, and — of course — drinking wine, along with the biological remnants of the process. (That included grape seeds and skins.) That's all pretty awesome, but what's most shocking was the time frame: The ancient winery had been in use 6,100 years ago. And the use of the word "winery" is important — even though people had been making wine for a while, this was the first sort of large-scale production facility ever found.

The team determined that the process is one that should sound pretty familiar: Grapes were stomped and pressed, then left to ferment inside the cave — which, incidentally, just happened to have the perfect environment for wine-making and storage. It turns out that it makes a heck of a lot of sense, too: Previous studies have suggested the domestication and cultivation of grapes go back to the ancient people of Armenia and Georgia.

North American cave art

Caves, says How Stuff Works, have different ecological zones. At the entrance is the aptly-named entrance zone (which gets lots of light), past that is the twilight zone (which gets a little light), and beyond that is the dark zone, where there is no light and only life that's adapted to live in a black void of nothingness. And it's in the dark zone of a cave just outside of Knoxville, Tennessee that a group of cavers discovered the first ancient cave art in North America.

According to Jan Simek, professor of anthropology at the University of Tennessee (via The Conversation), the group of amateur cavers was the first to lay eyes on the drawings of animals, birds, humans, and half-animal, half-human creatures in about 800 years. The art found in what became known as Mud Glyph Cave was ultimately linked to the Mississippian people, and what followed was further investigation and the discovery of 92 more sites across the American southeast (as of 2021). And strangely? They're all connected.

Simek later told CNN that the artwork was found to be from 6,000 to 500 years old, and it was only after documenting and compiling all the artwork that they realized it was all connected: It was all depicting a cosmology of an upper world, the so-called middle world — where plants, animals, and people lived — and a world that included the caves themselves, which "were places ... boundaries could be crossed."

Joseph Henry Loveless

Joseph Henry Loveless's story started in the late 19th century. According to The Washington Post, he was regularly arrested in connection with (among other things) his activities as a bootlegger and a counterfeiter, and got pretty good at escaping. He was a pretty awful guy, and everyone knew it. That included his first wife, who got a divorce — which was nearly unheard of at the time. After his divorce, he married a lady named Agnes. They were living the tent life outside of Dubois, Idaho, until May 5, 1916. That's when her remains — "hacked to pieces with an axe" — were discovered, and Loveless was arrested after attempting to high-tail it out of town. He predictably escaped and was never heard from again.

It wasn't until 2019 that his ultimate fate got a little less mysterious, and turned into a gruesome murder mystery. Way back in 1979, a family exploring a cave outside of St. Anthony, Idaho, found way more than they bargained for: a burlap-wrapped torso. Then, in 1991, another amateur explorer found a hand, and the following investigation turned up two legs and the other arm. Eventual technological advances led to the DNA Doe Project's involvement, and the remains were tested and connected to a then 87-year-old man: the grandson of Joseph Henry Loveless. While there are no official suspects in his murder, Clark Country Sheriff Bart May added, "Back in 1916 ... most likely, the locals took care of the problem."

His head has never been found.

Neanderthal stone circles

Archaeologists had first started exploring and documenting Bruniquel Cave in the 1990s, but it wasn't until 2016 that National Geographic reported on the findings in a single chamber, around 1,000 feet from the cave's entrance. It was there that archaeologists found a series of rings, constructed from almost 400 stalagmites (weighing a total of about 2 tons), cut to the same height and carefully arranged. In addition to one large circle that's about 22 feet in diameter, there was also a smaller semi-circle of stalagmites, with the remaining stalagmites stacked in several seemingly meaningful, central piles. While some naysayers think it's a weird coincidence that can be explained away by the behavior of hibernating bears, that, most say, is doubtful — particularly because they've also found traces that fires had been lit and burned among the circle, and bones had also been burnt at some time.

And it's the time frame we're talking about here that's really cool, because as much as it looks like the sort of thing early — but modern — humans would build, it predates Homo sapiens by a lot. The site has been radiocarbon dated to 176,000 years ago, which means that it was Neanderthals who not only organized the construction of these clearly meaningful patterns — and lit the deep cave while they were doing it.

It could change the way we think of Neanderthals: As study co-author Jacques Jaubert of the University of Bordeaux explained: "All this indicates a structured society."

45,000-year-old jewelry

It's no secret that people love their bling, and some people will go quite a long way to decorate themselves. It turns out, that's nothing new. The University of Oxford says that the study of Siberia's Denisova cave got really interesting in 2010, when archaeologists uncovered the pinky bone of a whole new group of human ancestors, the Denisovans. It was ultimately discovered that the owner of that bone was notable for a weird reason: They were the first "human hybrid," born of a Denisovan mother with a Neanderthal father.

Over the course of the 4 decades excavations have been going on at the site, researchers have learned a lot from the cave that's one of the few places found to have been occupied by a variety of ancient groups of humans. Among the items recovered have been some absolutely stunning pieces of 45,000-year-old jewelry.

According to The Siberian Times, the first piece was a stone bracelet made from the green mineral chloritolite. That was discovered in 2008, and since then, archaeologists added a white marble bracelet, pins made by sharpening the bones of a marmot, a marble ring, and another ring that clearly had some major value. After being broken, it had been rescued and turned into a pendant. It's unclear just who made and wore the jewelry, but Archaeology suggests the craftsmanship is from the mysterious Denisovans.

The largest crystals in the world

Geologist Juan Manuel Garcia-Ruiz says (via National Geographic) that the Cueva de los Cristales — or, Cave of Crystals — is "the Sistine Chapel of crystals," and that just might be an understatement.

In 2000, miners excavating a new tunnel found something unbelievable, tucked away in a cave 1,000 feet below Peru's Chihuahuan Desert and the Naica mountain: When they broke into the cavern, they found it was filled with some of the world's largest crystals, measuring up to 36 feet in length and weighing as much as 55 tons. (For some reference, that's about equal to the weight of nine elephants.)

Since then, there's been quite a bit of research done in the caverns — which is difficult, because according to the BBC, there's nearly 100% humidity inside, and the air is so hot that it's cooled as it enters the lungs. Geologists have discovered that the whole thing started forming about 26 million years ago, with help from some serious volcanic activity. The crystals themselves have been growing for hundreds of thousands of years, and now, there's a more pressing question than, "How were they formed?" That, says C&EN, is the question of how to protect them. Although the cave's natural state was perfect for the formation of these massive crystals, mining activities in the area have changed that environment, and they're at risk of dehydration and destruction.

An underwater graveyard filled with giant lemur bones

Madagascar is one of the richest, strangest islands in the world, filled with all kinds of species that aren't found anywhere else. That's been true for a long time, and when humans arrived there over 2,000 years ago, they ruined that, too. At the time, the island was home to megafauna — like giant tortoises and elephant birds, says MongaBay. And then, it wasn't.

While no one's been able to determine just what happened to cause such a seismic shift in Madagascar's ecosystem, they have gotten a pretty incredible look at just what species were lost. In 2014, paleontologists exploring the underwater Aren Cave discovered the floor was covered with fossilized remains of the long-extinct megafauna ... along with a handful of currently surviving species. There was a lot of cool stuff there, but Earth Archives says that the coolest were the remains of the gorilla-sized giant lemurs.

National Geographic says it's not clear how the bones got there — they're submerged under 82 feet of water, after all. It's thought they were carried there by the current, dropped, and laid undisturbed as they were first "defleshed," then semi-fossilized — and that's just what they found on the surface. The find was described as "extraordinary," and presented a unique opportunity for researchers to learn more about what the ancient landscape of Madagascar once looked like.

17 miniature coffins

On one June afternoon in 1836, a group of boys was exploring an area known as Arthur's Seat in Scotland — and they just happened to stumble across what's become one of the nation's weirdest mysteries. According to National Museums Scotland, the boys had stumbled across a little cave while on their adventures. The entrance to the cave had been blocked with a few pieces of slate, and when they looked inside, they found 17 miniature coffins, complete with figures that had been neatly dressed in little handmade clothes, then nestled inside the coffins. Yikes.

At the time, newspapers picked up on the find and started screaming about witchcraft, demonology, and black magic, because of course they did. Others suggested less outlandish explanations, like the possibility they were effigies representing friends who had died in faraway lands or had been lost at sea, and the dolls had been given proper rites in their place. That's actually pretty sweet, but the current theory isn't nearly as heartwarming.

It's now thought that the 17 coffins had been made — and buried — as a tribute to the 17 victims of notorious bodysnatchers William Burke and William Hare. They got their start when a fellow boarder at the house Hare was staying at had the misfortune of dying while owing him money, so they collected by selling him to a local anatomy school. Who made them? Why? Was it really a tribute to Burke and Hare's victims? It's unlikely we'll ever know.

An 11,000-year-old mine

Exploring caves is one thing, but exploring underwater caves is a whole other level of bravery. That's what two divers were doing in 2017 when they found something absolutely wild — after swimming more than half a mile into a cave beneath the Yucatan peninsula. And it started with the appearance of a threshold.

National Geographic says that once they swam across that definitely man-made threshold, they found themselves inside what was eventually determined to be an 11,000-year-old mine. A mine for what? Ochre: Ancient humans had once been there extracting that vibrant red pigment used in everything from cave paintings to funerary rites and as a mosquito repellent. The site was described as "a time capsule of human activity," and was complete with the remains of fires, tools, and even a series of cairns — piles of rocks that were built so miners could keep their bearings deep underground. Once that site was thoroughly documented, it ended up shedding some light on the use of several other mines.

And the ochre, archaeologists say, was of incredibly high quality — and there was a lot of it. Interestingly, beliefs about caves and the underworld suggest there was likely something sacred about the pigments sourced from so deep in the cave. California State University cave archaeologist James Brady explains: "It could be highly significant that this came from a sacred place, [and] that there was a journey into the cave especially to get it.

Kabayan mummies

The Kabayan Mummy Burial Caves of the Philippines are now recognized by UNESCO for their cultural significance, and it's safe to say that for those who buried their loved ones there, it meant even more than UNESCO can hope to communicate. According to the World Monuments Fund, the caves were used by the Ibaloi tribe, who practiced a form of embalming that was similar to what was found in ancient Egypt. Those who knew that their time on earth was limited would start the mummification process by drinking a salty concoction, and the process would then be completed over the weeks following the death. Once completed, the body would then be interred in decorative wooden coffins and placed in the ancient burial caves — where they were (relatively) recently rediscovered by loggers.

The ancient practices had come to an end with the arrival of 16th-century Europeans, and the mummies had endured for a long time. Once the caves were opened, it introduced all kinds of problems. From bugs and fungus to people being, well, people, it very quickly became necessary to protect the caves — while they're no longer used, the Ibaloi still consider them sacred.

The mummies have been extensively studied since the discovery of the caves, and some — like the chieftain Apo Annu — have been reinterred there. There's a really neat footnote to this, too: According to Archaeology, the study of the exquisite tattoos found on many of the mummies has allowed modern-day descendants to recreate their ancestors' tattoos.

The handprints of Mayan children

According to what archaeologists from the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Yucatan told La Journada Maya, they'd actually found the cave about two decades prior to publicizing their findings but kept it secret out of concern that it would be vandalized. The area was filled with relics left by the Maya, including bones and pottery, but the coolest part of the find was the 137 black and red handprints on the wall.

The cave — which is located beneath a sacred ceiba tree — is believed to have played a significant part in the coming-of-age rituals of young Maya who lived about 1,200 years ago. Archaeologist Sergio Grosjean says (via Reuters) that they believe children went to the cave to first leave their handprints on the stone in black, "which symbolized death, but that didn't mean they were going to be killed, but rather death from a ritual perspective." Then, they would leave the red handprints, "which was a reference to war or life."

It wasn't just an ordinary ritual, either: As the Smithsonian notes, the children who grew up during the era of the handprints were living through a seismic shift in their culture. It was a time of droughts so severe that it led to widespread death and the collapse of once-thriving cities — and it would have been a terrifying time to be alive.

A prep station for the dead

No one's easily getting to Scotland's Sculptor's Cave, and even if they do get there, the clock is ticking. Located in the sandstone sea cliffs of Moray, the cave is only accessible during low tide. Archaeologists have now made a full, 3D model of the cave to study from the safety of somewhere else — and it's a fascinating place, says LiveScience. It was first discovered in the 1920s, and according to Canterbury Christ Church University, archaeologists have unlocked more of the cave's secrets.

It's one of the few places where traces of Scotland's prehistoric dead have been found, and it was first used sometime around 1000 BC. That, says the University of Bradford's Ian Armit (via LiveScience), is when prehistoric people were practicing "excarnation, or exposure burial": The bodies were left to the elements, where they would slowly decompose and decay — and there were signs that all the while, the living would come to visit.

In addition to some of the bones bearing marks that seem to indicate they were defleshed and polished, there was also a plethora of Pictish carvings, and a site for visitors to cook while checking on their ancestors. The site was in use for around 1500 years, and things only came to an end in the 4th century AD. That was a little after one of the most surprising finds: In the 3rd century, the cave was the site of the execution and decapitation of at least nine people.

A tiny family member

We're used to hearing about different species of animals, but different species of humans? Yes! Most surprising is how little science knows about them, and when an announcement came in 2004 that scientists had discovered the fossilized remains of a very small human who had lived near and apparently died in Indonesia's Liang Bua cave, well, National Geographic says that things get a little ... problematic.

Not long after a group of scientists from Australia and Indonesia announced they had discovered a new species of human and named it Homo floresiensis, skeptics started claiming it was anything but a distinct species — and most tragically, the original bones were reportedly damaged by a big-deal sort of paleoanthropologist who was studying them in hopes of disproving the existence of the people nicknamed the Hobbits.

Today, LiveScience reports that we know those naysayers were wrong, and that very first skeleton really was our first look at a new species of human. In life, the 30-year-old woman called LB1 would have stood about three-and-a-half feet tall, and more of her species have since been found. Nat Geo says they lived from 100,000 to 60,000 years ago and adds that skeptics have still maintained that there was a connection between these ancient people and modern-day pygmies still living in the area. DNA testing has ruled out the idea the two are related, which means something just as interesting: Independent groups of humans evolved the same way ... twice.

A literally toxic hell-on-earth

Romania's Movile Cave has been isolated from the rest of the world for 5.5 million years. The Digital Journal notes that's about the same time our ancient ancestors were just sort of starting to think about evolving into humans, and it's also when the cave was sealed by a falling piece of limestone. When researchers popped the top in the 21st century, they found a world that had evolved completely independently.

Discovered in 1986, the cave is only accessible via a long shaft, then a series of limestone tunnels. While it's a relatively pleasant 77 degrees Fahrenheit, it smells like rotten eggs thanks to a pool of sulphuric water at the bottom — which spews hydrogen sulfide when anything breaks the surface. That means it's incredibly deadly, and spending more than a few hours there would lead to massive organ failure.

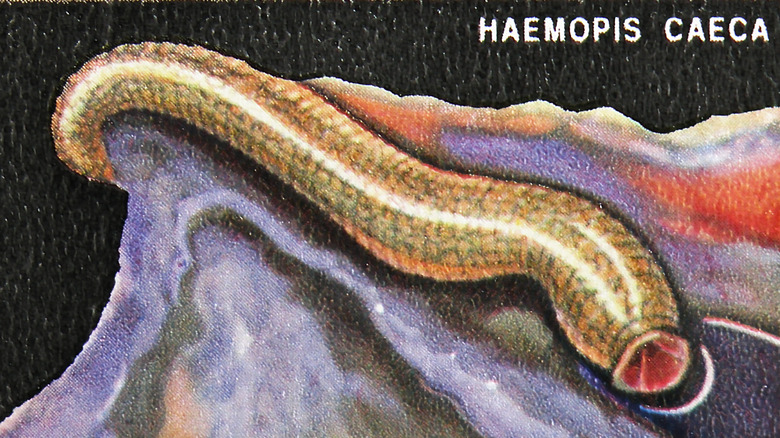

The life that's evolved there is just as weird. One of the basic building blocks is a type of chemosynthetic bacteria that exists on carbon the way life on the surface needs oxygen. (And yes, scientists are hoping that if they can learn more about these life forms, they might get some ideas on how to deal with various greenhouse gases.) LiveScience says that more than 50 unique species have been discovered, and most are the creepy-crawly sort. In addition to cave leeches, snails, scorpions, and spiders, there's also the "king of the cave," a venomous centipede that is only about two inches long, but is so deadly it's the cave's apex predator.

Carvings by the Knights Templar ... maybe

In 1742, a group of workmen was sent to the butter market in Royston (near Cambridge). They moved a millstone that they'd found embedded in the ground, and because this was the mid-18th century, they volunteered a young local boy to get lowered into the hole and find out what was down there. (Ah, the good old days.) What he found is now called Royston Cave, and the man-made cave had been excavated from the chalk and then covered with carvings.

Along with a section that tells the story of the resurrection of Christ, there are also panels dedicated to St. Christopher, St. Laurence, St. Katherine, and a military figure believed to be St. George. There's also a scene of the crucifixion, imagery of King Richard I, and strangely, there are also pagan images of figures like Sheila-na-gig, an ancient fertility goddess. Scores of small figures remain unidentified, and beyond the fact that it was likely excavated and carved in the mid-15th century, no one has any idea what it is.

There is, however, one popular theory, and that's the story that it was a secret meeting place for the Knights Templar. (Among the carvings is one thought to be a memorial to the Templars' famous Jacques de Molay.) There are other theories, though, including the possibility that it was the one-time home of a hermit, or that it was carved as a private chapel for Lady Roisia, wife of the steward of William the Conqueror. Who knows!