The Untold Truth Of Ed Hardy

You may not have heard of tattoo artist Ed Hardy. You may not have even heard of his brand of clothing, which the LA Review of Books charitably calls "clothing for people who make the 'rock on' salute in Facebook photos." (Urban Dictionary is much harsher.) But you definitely know his distinctive style of tattooing: old school American naval designs full of skulls, roses, vivid colors, and twisting, spidery black outlines. Ed Hardy is the most famous tattooer alive, the godfather of a new generation of artists and aficionados.

He elevated tattooing to new heights of technique and connoisseurship, shocking the art world: A New York Times article from 1995 covering an Ed Hardy exhibition screams, "Is it art?" But more importantly, Hardy brought tattoos, once the exclusive preserve of sailors and social pariahs, to the respectable middle classes. The koi fish sleeve that peeps out under the suit jacket of the guy in accounting and the inspirational quote burned into your teacher's foot are Ed Hardy's doing.

A fascination from childhood

Ed Hardy was born in 1945 in Newport Beach, California, according to CNN. He was only 3 when art began to fascinate him, and his mother encouraged him to draw with colored pencils.

The young Hardy's best friend was the son of a veteran who had served in World War II, as Hardy related in an interview with Artnet. This man had a number of small tattoos from his time in the service, and Hardy was amazed by the exotic, dangerous-looking artwork burned into his skin. Still in elementary school, Hardy began to visit a local tattoo shop, whose proprietor let him copy tattoo designs onto paper. He even hung some of these copies in the shop window, making him the first-ever host of an Ed Hardy exhibit. Hardy's interest became a passion, and he soon started a "tattoo parlor" in his own house with a homemade business license, colored pencils, and ladies' eyeliner for tattoo pens.

Hardy the art student

Even in the 1960s, tattooing had an aura of taboo. Men got them in prison cells, with homemade ink, or between brawls in the red-light district of some seedy port town. Few, if anyone, considered tattoing an art at all.

So Ed Hardy must have raised some eyebrows at the San Francisco Art Institute when he told people about his passion. Obviously, the institute didn't have a tattooing program; Hardy was there to study printmaking, an applied art with considerable overlap with tattooing (per the Los Angeles Review of Books). In his autobiography, Hardy explained, "I loved artwork that had a specific craft, stringent demands involving tools and techniques that had to be done a certain way. ... I liked the idea that it was a multiple original. I liked the democratic, anti-elitist nature of that. It was a people's art."

In 1967, Hardy's life was changed by a book of photos from Japan depicting the traditional, full-body irezumi tattoos associated with the Yakuza. Tattooing, he realized, was his destiny. He got himself tattooed for the first time, turned down a graduate scholarship to Yale, and traded his letterpress for a pen.

The journeyman tattooer

The new artist's first port of call, as it were, was the shop of Norman Collins — better known as "Sailor Jerry" — of Honolulu, Hawaii. According to the official Sailor Jerry website, the legendary master tattoo artist started his career in the 1920s, and by the late 60s, he was a gruff, pipe-smoking licensed sea captain with a stunningly original oeuvre. Sailor Jerry was the first American to incorporate elements of traditional Japanese and Pacific Islander tattoos into his own designs. Hula girls, pierced hearts, rum bottles, anchors, and swallows were his stock in trade, and he would refuse service to anyone who had already been tattooed by one of his imitators.

Sailor Jerry was hard to impress, but he took the passionate young Ed Hardy under his wing, teaching and encouraging him. When Hardy returned to San Francisco after a year, the old sailor kept in touch, sending letters and designs. According to his website, Sailor Jerry stipulated in his will that upon his death, his shop would go either to Rollo Banks or Ed Hardy. Banks ended up taking over the shop, but Hardy set up his own, Realistic Tattoo, which made history.

Modern tattoos, by appointment

Realistic Tattoo was the first shop of its kind — you had to make an appointment, and the actual tattooing didn't start until after a long consultation with the artist (per the Los Angeles Review of Books). Although this is a familiar model in the 21st century, previously, you would show up drunk and hope for the best. Hardy's shop was making art to measure — not unlike like a bespoke tailor, only cheaper. The house style was like Sailor Jerry's but distinctive: Asian-style dragons and tigers, geishas, hearts, and short phrases in spidery letters.

Slowly, Realistic's reputation spread, spawning imitators and a devoted fan base. In 1982, Hardy and his wife founded the first tattoo magazine, "Tattootime," which included international tattooing news, essays on the craft, and reminiscences from famous tattooers that were sometimes ... colorful. (Per the LA Review of Books, one story that ran in "Tattootime" told of a female artist who burned off a soldier's chest tattoo by pouring acid on him and waiting for it to eat off his skin.)

By the 1990s, thanks to Hardy, tattoos were no longer for sailors and degenerates. Koi fish, flowers, and sailor stars were everywhere.

Into fashion, out of fashion

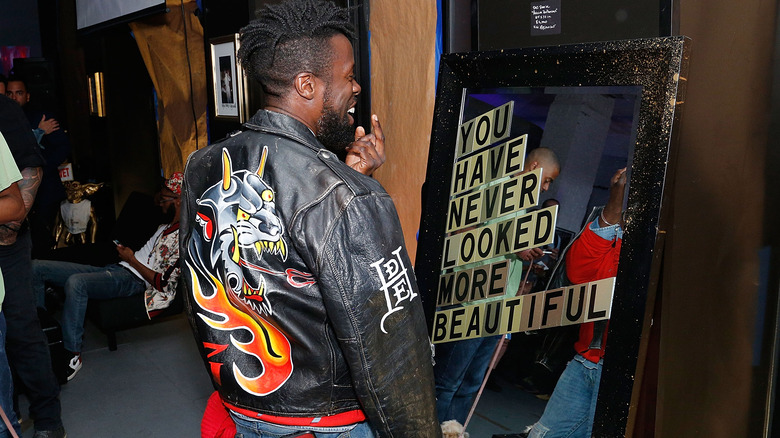

Many people know Ed Hardy less by his tattoos than by the clothing brand that bears his name. As noted before, the brand has a certain reputation for trashiness, like the Jerry Springer show in graphic T-shirt form.

Whether or not the brand deserves that reputation, CNN takes care to underscore how removed it is from Hardy himself. In 2003, two businessmen in the fashion industry approached Hardy for permission to use his distinctive designs on T-shirts. Hardy agreed. The new line caught the eye of French fashion mogul Christian Audigier, creator of Von Dutch and other brands, who convinced Hardy to sell him the master license. As a business move, it was brilliant: In 2009, sales had passed the $700 million mark worldwide, and celebrities like Madonna and Catherine Zeta-Jones sported Ed Hardy-branded duds in front of the cameras.

It didn't take long, however, for the brand to start sinking. "Morons dehumanized it," said Hardy, who sued Audigier in 2009, eventually settling out of court. Luckily, the brand and the man are different entities, and Ed Hardy himself is still working and exhibiting his art worldwide.