The Untold Truth Of The Man Who Sold The Eiffel Tower

After conducting an extensive investigation he reported to Smithsonian, historian Tomáš Anděl determined there is no evidence Robert Miller was ever born. As is the case with many confidence men, Miller's early life is so riddled with rumors it's difficult to discern the facts. Unless a con artist is performing the signature trick of their trade, they prefer to leave no trace. According to Smithsonian and U.S. court documents (via Casino), Robert Miller (or "Victor Lustig," as he would later be known) is believed to have been born in October 1890 in Hostinné, Bohemia, which later became the Czech Republic.

In lieu of facts about Miller's (or Lustig's) early life, we have rumors. According to Headstuff and Smithsonian, Lustig was reportedly born to either a mayor, a bourgeois family, or poor peasant farmers, depending on who you ask and when you ask them. What Victor told them depended on what he wanted from them. Pretext is everything — Victor provided so many tales about his beginning that he ultimately provided none. But after all, that's the point, and it's exactly what differentiates a confidence trick from an ordinary trade: the confidence man gives up nothing.

Call him Victor Lustig

Born to a long line of wealthy Bohemian nobles, Count Victor Lustig had grown accustomed to an extravagant life. With little want for status or money, the Count was plagued only by simmering political discord. This discord would come to threaten not only the status afforded him by his birth, but also his family, his freedom, and nearly his life. Shortly after the fall of the Bohemian Kingdom, the fallen nobleman fled to France, then decided to board an ocean liner and try his luck in New York City. Thankfully, he still had his fortune. He was using it to devise inventions that he hoped he could one day sell upon starting a business.

This was the lie Robert Miller, or "Victor Lustig," told dozens of wealthy travelers aboard ocean liners in the early 1920s. According to Smithsonian, the con hinged on Lustig's "invention," the "Rumanian money box" — a box that, Lustig claimed, could perfectly duplicate real currency. Lustig would ensure the box casually drew the mark's attention, then wait till they begged him to buy it. After refusing, he would eventually acquiesce — but only for an exorbitant price.

The box, a steamer trunk outfitted with useless gears and levers, took "six hours" per cycle. According to Casino, Lustig would load the box with just enough authentic bills to last 24 hours (before the buyer could realize they'd been conned) — giving the "nobleman" just enough time to escape.

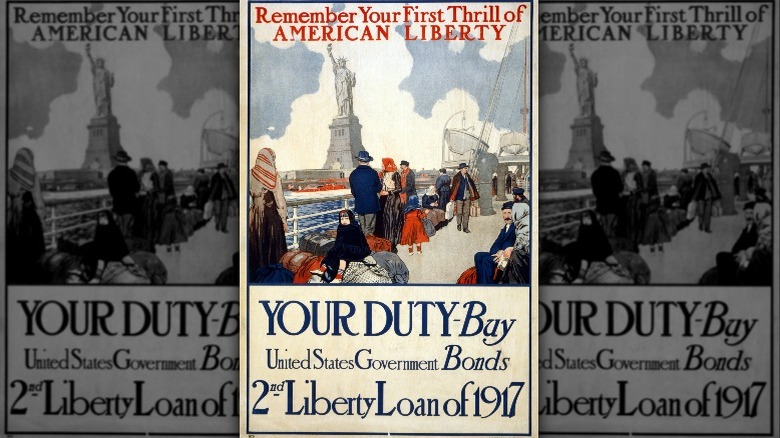

Call him Robert Duval

Victor Lustig pops up again in 1922 — this time, as "Robert Duval." According to Headstuff, Robert Duval was in possession of Liberty Bonds he hoped to sell to a Missouri bank in exchange for property. After bringing $22,000 in authentic bonds to the bank, Duval (or Lustig) used old-fashioned sleight of hand to switch the envelopes, handing the empty ones off to the tellers. (He even convinced them to pay cash for another $10,000 in bonds to cover his "operating expenses," according to Headstuff.) As always, Duval then disappeared.

He'd chosen a powerful mark. According to Headstuff, American Savings Bank hired private investigators to track down "Duval" and extract the money he owed them. "Duval" was found. Using a combination of charm and malevolence, "Duval" was somehow able to convince the investigators that it would greatly tarnish the bank's reputation if he was brought in. If word got out, he told them, it could be bad for the bank. In addition to convincing the bank to drop the charges, "Duval" even convinced them to pay him a bribe of $1,000 so he'd "stay quiet."

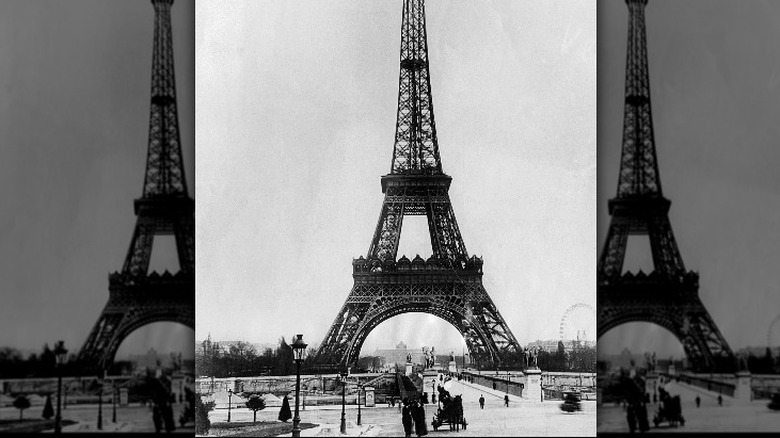

Call him French Minister of Posts and Telegraphs

According to Headstuff, the Eiffel Tower was initially constructed as a temporary monument for the World's Fair. The French had later decided to keep it, but the cost of maintenance was crippling. Many Parisian natives saw it as an "eyesore," and some debated taking it down.

Appearing again as Count Victor Lustig, this time as a French Minister, Lustig hired a forger to compose fake government stationary, then mailed letters to the five most prominent scrap metal dealers in Paris. The Count divulged that the government had decided to do away with the "eyesore." The men had been chosen as potential buyers — but only under condition of absolute secrecy, as the decision had not yet been revealed to the public.

Lustig arranged a tour of the Eiffel Tower for the five men, then invited the "buyers" to meet him at a hotel known for hosting diplomats. After inviting his guests to bid against each other, Victor then selected his mark — Andre Poisson — who even paid Lustig a bribe to secure the deal, per Smithsonian. With the bribe and "deposit" on the Tower in tow, Victor fled to Austria (via Headstuff), awaiting news of the scandal to break.

When Poisson was too embarrassed to report the fraud, however, Victor returned to France and pulled the scam again. The second time, he got caught — but not before he was able to flee to the United States.

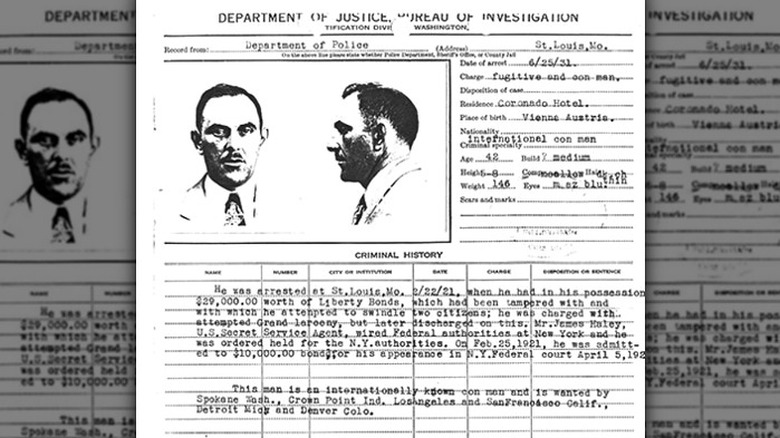

Call him Wanted by the FBI

During his time in the United States, Victor Lustig (otherwise known as Victor Foster, Robert Lamar, George Kane, Charles Nevera, Edward Schaffer, Frank Herbert, Albert Phillips, and John Kane — via arrest documents published by Casino) pulled dozens of cons, including an attempted con on Al Capone, according to Headstuff. His largest and most involved operation involved counterfeit currency.

With the help of chemist Tom Shaw and professional engraver William Watts, Lustig produced over $1 million in counterfeit currency — so much that at one point New York banks estimated they were finding over $100,000 in "Lustig-Watts" notes every month, Smithsonian reported. The scale of the operation caught the attention of the federal government. Eventually, Lustig's partner turned on him. According to Smithsonian, rumor has it that he was found when his own mistress reported him.

Lustig was brought to the Federal House of Detention in New York City, known for its reputation as a secure facility. Pretending to be a window cleaner, Lustig escaped the day before his trial (according to Headstuff). After escaping the facility, he even reportedly bowed to onlookers before he fled the grounds. Lustig was found a month later in Philadelphia, tried in court, and sentenced to 20 years in Alcatraz.

Throughout his imprisonment, he complained of ill health — according to Smithsonian, his captors assumed he was once again "faking." He was transferred to a secure medical facility in Springfield, Missouri. It turned out that this time, he wasn't faking. There, in 1947, Robert Miller — or whoever he was — died of complications from pneumonia.