Things We Know About The Bottom Of The Ocean

The majority of earth's surface is ocean, but more than 80% of it has never been explored, mapped, or even seen by human beings. The deepest parts of the sea are freezing, completely dark, and impossible for humans to withstand outside of a specially designed submarine, but even in these harsh environments some creatures have found a way to thrive.

The bottom of the sea is far from uniform. As described by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, both the longest mountain range in the world and the tallest mountain peak can be found in the depths of the sea. There are deep trenches and chasms, flat plains, and even salt lakes under the waves.

The shallowest sea floor is close to the shore, and known as the continental shelf. These areas are typically flooded with sunlight and teeming with life. Traveling deeper, the steep continental slope tips down into a part of the ocean so deep that no sunlight can reach it called "the Midnight Zone." This levels out again (continental rise) in an area more than 13,000 feet deep. This region is known as "the abyss." More than 70% of the ocean floor is in the abyss, and it's called the abyssal plain. At first glance, this massive, flat, deep ocean floor might seem uninhabitable, but fascinating ecosystems have adapted to this harsh, sunless environment, creating communities of life unlike any other on the planet.

High pressure

The majority of the ocean's depths are unexplored, primarily because the deeper the water gets, the more difficult it is to exist there.

Below the surface, water presses in on all sides. This is known as hydrostatic pressure. As noted by The Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, the average amount of pressure felt when at the surface or the shore — the amount most people are used to — is referred to as 1 atmosphere. The deeper into the water one goes, the more hydrostatic pressure there is. At just 33 feet below the surface, the amount of pressure is double the amount at the surface. The average depth of the ocean floor is approximately 2.4 miles deep, but there are areas where it can be as deep as 6.8 miles from the surface. Every 33 feet down is the equivalent of another entire atmosphere pressing in from all sides, so the pressure gets pretty high.

For human beings, this amount of crushing pressure would be immediately deadly. In order to explore these depths, special vehicles and robots have to be designed to withstand enormous amounts of pressure — between 380 and 1,100 atmospheres — without cracking.

No light

Sunlight is the source of heat, light, and energy for most of the planet, but in the three deepest layers of the ocean, there is no sun at all.

As described by the National Weather Service, the zone closest to the surface is known as the sunlight zone, because the sunlight illuminates and warms the water of this layer. Around the world, temperatures in the sunlight zone range from 28°F to 97°F. The region below this is called the twilight zone because while it is very dark, some sunlight still reaches this layer. At about 3,300 feet below the surface the midnight zone begins. This zone is completely dark at all times, and fittingly, it is approximately 39°F. Next comes the layer of the ocean known as the abyssal zone. It is just as dark as the midnight zone and always near freezing. For most of the sea, this is as deep as it can get. However, some of the deepest sea trenches have another name: the hadal zone, starting at 19,700 feet below the surface and stretching as deep as the ocean goes.

In order for life to survive without sunlight, creatures in these deepest parts of the sea must find other sources of energy.

Diverse lifeforms

Despite the crushing pressure and the total darkness, the deep sea is earth's largest habitat, even if studies estimate that more than 90% of the ocean's creatures have yet to be discovered and classified. The animals that have evolved in this environment may look other-worldly — but each adaptation allows them to survive at the bottom of the ocean.

NASA researchers (via BBC) have investigated how deep sea creatures like gelatinous translucent snailfish can endure the pressure from water crushing in on all sides. It is believed that they have developed an enzyme that counteracts the weight pressing down on them by causing proteins in their cells to take up more space. As seen in BBC Earth's "Blue Planet," many of the creatures that live in the sunless parts of the oceans are bioluminescent, giving off their own ghostly glow.

As described by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, the deep sea is home to many creatures that actually thrive in this harsh environment, from the strawberry squid, whose massive eye is adept at seeking out bioluminescence in the pitch black water, to the feather star, which resembles a flower blooming on the sea floor until its "petals" begin to ungulate and it zooms away into the darkness.

The deepest point

The deepest part of the ocean is in the Mariana Trench. It is massive, almost 35 miles across and seven miles deep. As described by Smithsonian Ocean, if Mount Everest was at the bottom of the Mariana Trench, its peak wouldn't break the surface.

The very deepest point is known as "Challenger Deep," a smaller trench in the bottom of the enormous Mariana Trench, which is approximately 35,800 feet from the ocean's surface. As detailed by National Geographic, even at the deepest point of the ocean, life exists. Amphipods (a kind of crustacean) that managed to grow to two inches long — more than twice the length of those found in shallow waters — were discovered in Challenger Deep. These creatures are believed to swarm below 30,000 feet. Nothing grows and there is little to eat at these incredible depths, but these creatures are able to eat wood that sinks from the surface. It is believed that some of their diet comes from shipwrecks.

Brine lakes

While lakes might intrinsically seem like something that could only exist on land, they can also be found at the bottom of the ocean. As impossible as it might seem, brine lakes on the ocean floor appear to have a surface like they would on land. They even have their own waves that don't extend to the sea around them.

As explained by Smithsonian Ocean, these lakes are separate from the oceans around them because their water is much denser and saltier than the rest of the sea. This causes the lakes to sit on the ocean floor rather than flow with the rest of the water. It is believed that these lakes originated in an ancient ocean, dating all the way back to the Jurassic. As stated in Scientific American, the water in these "lakes" is so dense that submarines have been able to land on their surface.

The brine in these lakes is full of methane, which would kill most animals that might wander into the lake, though there are forms of bacteria and other single-celled organisms that can breathe methane that live in the brine lakes. Sometimes daredevil mussels are attracted to these bacteria, so they may be found near the edges of the brine lakes.

Abyssal plain

70% of the seafloor is located in the utterly dark abyssal zone, in which the extremely vast and flat seafloor is known as the abyssal plain. Some portions are rocky, while others have soft substrate. While these plains may appear uninhabited compared to the populous sunlight zone, this area is home to a variety of creatures. As stated by Blue Habitats, these ecosystems are some of the least observed in the world, and there are many things about life in the abyssal plain that are still a mystery.

The abyssal plain is located between 9,800 and 19,685 feet below the surface. The seafloor this deep is very cold and provides little opportunity for sea creatures to feed. As explained by Smithsonian Ocean, less than 5% of potential food from the surface makes it to the abyssal plain. Debris from the sunlight zone drifts deeper, but the majority of it is eaten by the creatures that live above before it can reach the seafloor thousands of feet below.

Despite this, some creatures have evolved to live in these harsh habitats. Squat lobsters and prawns live there, along with sea cucumbers, mollusks, worms, and echinoderms (spiny invertebrates like starfish and sea urchins). It is believed that there are also creatures that live in the soft sediment, but the only evidence that has been discovered so far are the burrows and trails they leave behind.

Canyons

Not all of the ocean is as flat as the abyssal plains. As described by Smithsonian Ocean, there are deep undersea canyons that stretch for hundreds of miles. As on land, this landscape creates a wide variety of habitats, not only at the bottom of the canyon but in its rocky walls. These deep canyons, stretching from the sunlight zone to far deeper and darker waters, are often full of life. There are opportunities for good meals for creatures of all kinds. Part of this is due to water currents created by the canyon's shape, and debris from the surface is carried down into the narrowing canyon.

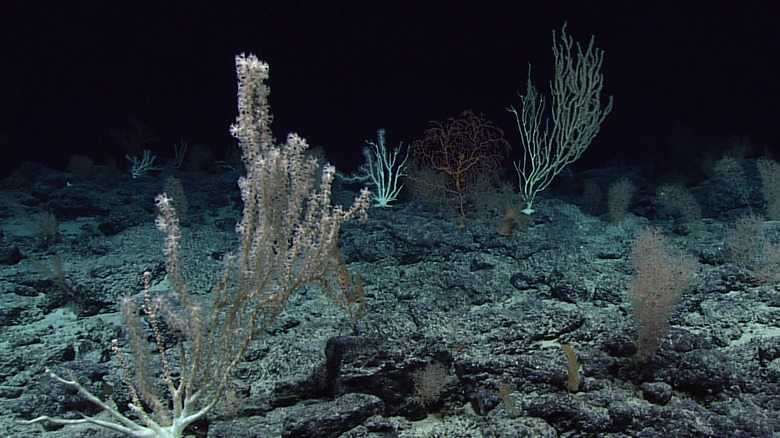

The sides of the canyon provide an ideal home for corals and sponges, while fish hide in the ledges. The bottom of the canyon is often soft and muddy, which lets mollusks and worms burrow. Algae grows in the water nearer to the surface, which supports populations of fish, which in turn attract larger creatures. As detailed by NOAA, squids, octopuses, and crabs thrive there. Sharks are attracted to the canyons to feed. Higher numbers of whales, even endangered whales, have been discovered in New England (or Mid-Atlantic) canyons.

It is also believed that the geography of individual canyons impacts the entire ocean. Canyons can influence the temperature of the sea around them, create strong currents, and affect the migration of all kinds of fish, from tuna to sharks.

Seamounts

Canyons are not the only enormous geographical feature under the sea. Underwater mountains, called seamounts, rise up high from the seafloor. In fact, the tallest mountain on earth is located in the ocean. Like canyons, seamounts have an impact on ocean currents.

As explained by NOAA, some seamounts are incredibly old, and it is believed that there are around 100,000 seamounts over 3,000 feet tall. For example, Bear Seamount, which can be found in the Atlantic Ocean, is estimated to be 100 million years old. Even the tallest mountain on earth, called Mauna Kea — which stands more than 30,000 feet tall, approximately 1,000 feet taller than Mount Everest – is actually a seamount. Like most seamounts, Mauna Kea is a dormant volcano. As explained by the Woods Hole Oceanic Institute, this is because many seamounts are located at the edges of the earth's tectonic plates, where magma comes up through the earth's crust.

Seamounts create many habitats for various forms of sea life that would not be able to survive anywhere else. Their peaks interrupt currents, driving plankton and other sources of food down their slopes. Deep-sea corals live on their slopes. Although there is no energy from the sun for these corals, they are able to survive by filtering organic debris that drifts down from the surface. These communities of corals can exist for hundreds or even thousands of years, providing shelter for many sea creatures, some of which only live under these specific conditions.

Hydrothermal vents

While the majority of the deep sea is frigid, there are a few places where the water is scalding hot. These are known as hydrothermal vents, and they are teeming with life.

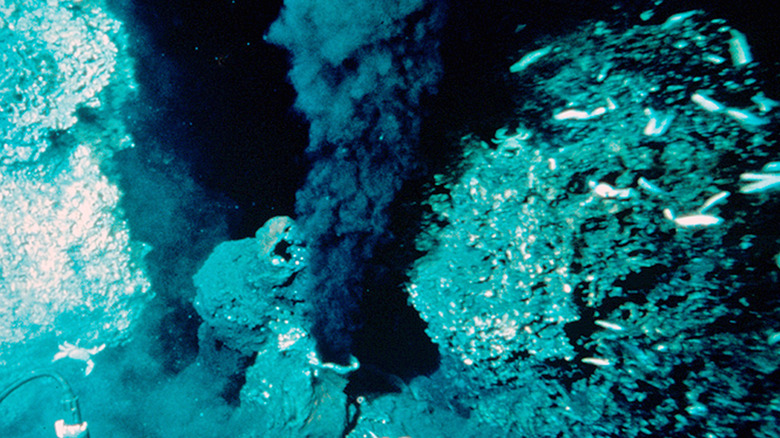

These are places where columns of billowing smoke jet up from the seafloor, and as described by NOAA, volcanically active areas create the vents that support these unlikely ecosystems. Sea water flows through cracks in the earth's crust. The water that comes back into the sea has been heated up to around 700°F by the magma below. The only reason the water doesn't boil is because of the enormous pressure at the bottom of the sea. That water is also infused with minerals, formed when the hot hydrothermal fluid meets the chilling seawater. As the water cools, the minerals solidify, creating vents. Some are black with iron sulfide, called "black smokers," while others, "white smokers," come from barium, calcium, and silicon.

As detailed by Smithsonian Ocean, organisms are able to live without the sun's light because of bacteria which use the minerals from the vents instead. This has allowed for creatures and communities unlike any other. One example is the yeti crab. As explained by MBARI, these fascinating animals live over 7,000 feet below the surface, around the hydrothermal vents near Easter Island. They have been observed holding their hairy claws over the water surging out of the vents. Colonies of bacteria live in this hair, and it is believed they may be collecting them intentionally, as a food source.

Whale falls

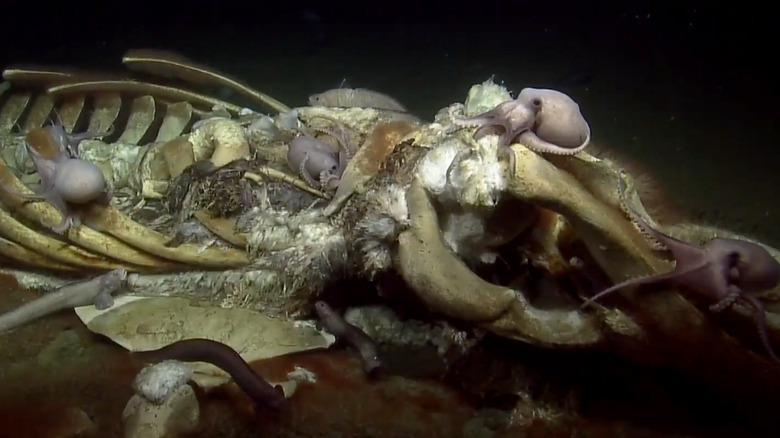

Food on the ocean floor is scarce, since very little actually makes it down that far. When a whale dies, however, it is so massive that it supports an entire ecosystem. As explained by Smithsonian Ocean, whales generally die in shallower, sunlit waters. Slowly, they sink to the ocean floor. These events are called "whale falls," and, although they take place at the very bottom of the ocean, they can have the highest animal density of anywhere in the sea.

No part of the whale is wasted. Sea scavengers of every kind flock to the body of the whale. It doesn't take long. Within hours, it attracts all kinds of shark, fish, and crustaceans to the feast. As they feed, smaller particles are scattered, providing food for nearby anemones, mollusks, and worms on the seafloor. Even though the bulk of the whale is consumed by larger animals, communities of thousands of worms are supported. Some animals have even adapted to be able to eat the bone. Whale falls are also havens for bacteria – almost 200 different kinds have been discovered on a single whale fall.

Exploration

Considering the extreme conditions at the bottom of the ocean, it's not surprising that more than 80% of the ocean is still unexplored. Scientists and engineers are developing new ways to explore even the deepest parts of the sea.

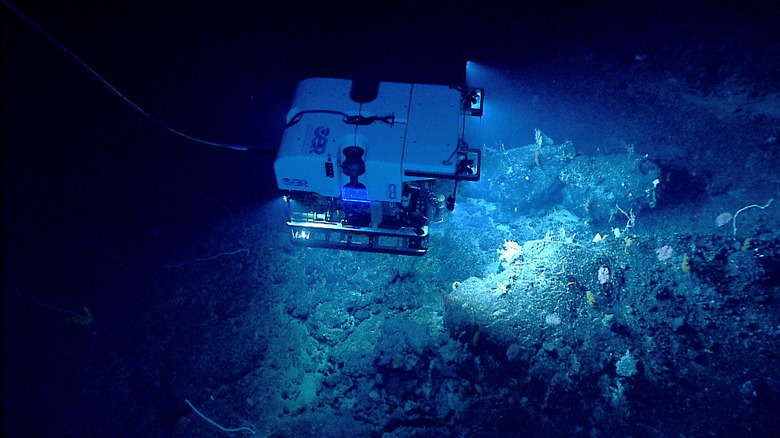

As described by Smithsonian Ocean, one option is autonomous water vehicles (AUVs) which are robot explorers, programmed to travel to specific areas of the deep sea and bring back information. There are also remotely operated vehicles (ROVs). These robots are attached to a ship on the surface, where human operators can control their movements and watch what happens on monitors. Naturally, there are also hybrids, which are somewhere in between. Sometimes, though, humans still go on these deep sea exploration missions. Human occupied vehicles (known as HOVs) are able to travel to the deep ocean and keep the people inside safe without cracking from the extreme pressure. Some even have "arms" that the explorers inside can use to collect specimens.

NASA, known for its space missions, is also exploring earth's oceans. As stated by the BBC, it is hoped that by learning more about our own ocean and developing technology that can explore it, humans can learn more about what it's like on other planets. One AUV called "Orpheus" has been built by NASA's engineers using similar technology to the Perseverance Mars Rover in order to map the ocean floor. "If it works," said deep sea biologist Tim Shank in January 2022, "there is no place in the ocean you can't go."

Human impact

In 2019, explorer Victor Vescovo took a submersible deep into the Mariana Trench, breaking the record for the deepest ever dive. He stayed in its depths for four hours, exploring the never-before-seen waters. Alongside numerous deep sea creatures, Vescovo found a plastic bag.

As reported by the BBC, it's known that millions of tons of plastic end up in the ocean every year, but Vescovo finding a man-made object in a place in the ocean that no human had ever seen before has become a symbol of mankind's influence on the sea. As described by The New Yorker, the deep sea is at risk from not only plastic waste, but all types of pollution, ocean acidification, and climate change as a whole. How much damage has been done already is not entirely known.

Angela Benn of the National Oceanography Centre (via phys.org) explained, "There needs to be a much greater understanding of the relative impacts of human activities on the deep seafloor, and in particular how these activities affect seafloor ecosystems and biodiversity."