The Worst Nuclear Disaster In U.S. History Explained

The partial meltdown at Three Mile Island in 1979 is thought to be the worst nuclear disaster in American history, but the Church Rock uranium mill spill in New Mexico, which occurred just four months later, actually released even more radioactive material into the environment. To say that the spill was cleaned up would be a major overstatement. Decades later, the water and land remain contaminated and health problems persist in the region. After the spill, 240 Diné filed a class action against United Nuclear and the case was settled in 1985 for $550,000, but that was the most that residents would see from United Nuclear in response to the spill.

Although the Church Rock mill spill was bad, it was just a high point of water contamination from uranium mining, which continued to devastate local water and land. And the fight against radioactive water contamination continues into the 21st century. In 2021, the Navajo Nation continued to fight against uranium mining and in October of that year, the Eastern Navajo Diné Against Uranium Mining (ENDAUM) petitioned the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, arguing that the approval of Hydro Resources Inc. mines "violated the human rights of Navajo Nation residents."

But while it's going to take decades to clean up the residue of 20th-century uranium mining in the United States, it's worth recognizing what that really entailed for the Indigenous people in the affected communities and whether it's worth subjecting another generation to that. This is the worst nuclear disaster in U.S. history explained.

Uranium mining

Beginning in the 1950s, New Mexico and the Navajo Nation became the main source of uranium production in the United States. Between 1948 to 1982, New Mexico was producing 41% of the uranium in the United States and during the same time period, up to 30 million tons of uranium ore were mined from Diné (Navajo) lands. Many who worked as uranium miners were Diné and, per Colorado State University, they moved their families to towns near the mines. But although the U.S. Public Health Service knew about the health effects of uranium mining, they didn't tell the miners. Instead, they "enrolled more than 4,000 miners in the study without their consent" to monitor the health effects of radiation. Other indigenous groups including the Hopi and the Arapaho were also exploited.

According to "Yellow Dirt" by Judy Pasternak, government demand for uranium had fallen by 1971, and with no longer a price guarantee plus a drop in prices, many mining companies abandoned their uranium mines. But uranium being sold "on the private market," some companies got into the commercial side of uranium, leading to 22 commercial nuclear power plants in the United States by the 1970s.

And even before the Church Rock mill spill, the U.S. Government Accountability Office writes that the Department of Energy estimated that "millions of gallons of water contaminated by mill tailings [waste material] were released into the groundwater over the life of the [mining] sites through the unlined ponds."

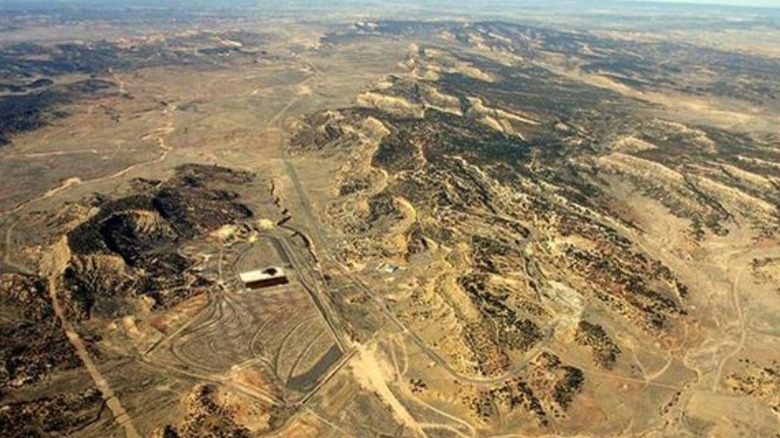

The uranium mill in Church Rock

One of the companies that sought to quickly get in on the commercial uranium market was the United Nuclear Corporation, which created a uranium mill in Church Rock/Kinłitsosinil, New Mexico. The Church Rock Mill, which opened in 1968, is one of "the largest underground uranium mines" in the United States. Employing over 200 Dine people to work at the mine, the Church Rock Mill produced over two million pounds of uranium oxide annually which, according to the American Public Health Association, was "enough to supply annual reload fuel to approximately 5 nuclear power plants."

For every ton of uranium, there were several thousand tons of nuclear waste. This nuclear waste from the ore extraction process is known as tailings, "a sandy waste containing heavy metals and radium." But instead of leaving the tailings in piles, which "Congress [was] up in arms about," United Nuclear decided to add water in order to liquify the mill waste and store it in a "large earthen dam," Pasternak writes in "Yellow Dirt."

Described by the company to be "state-of-the-art" the dam, which was little more a man-made pond, was supposed to keep the radioactive wastewater out of an arroyo that led to the Rio Puerco, a tributary of the Rio Grande that delineated the southern border of the Navajo Nation.

The dam breaks

Between 5:30 and 6:30 AM on July 16, 1979, the dam of the Church Rock uranium mill burst, leading to a flood of radioactive tailings. "Yellow Dirt" writes that due to a 20-foot breach opening on the dam overnight, around "93 million gallons of radioactive liquid poured from the pond into the arroyo" and drained into the riverbed. In addition, there were up to 1,100 tons of milling waste that were also released into the Puerco, making it the "single largest release of radioactive material in U.S. history." An astonishing 46 curies of radiation were released, compared to the 13 curies released during the Three Mile Island incident just four months earlier.

The Navajo Times reports that when Church Rock Chapter Vice President Robinson Kelly heard the rush of roaring water in the early hours of the morning, he also simultaneously smelled an incredibly foul odor. Kelly would later also go to the Rio Puerco, also known as "Puerky," and found that it was "filled to overflowing with rushing water," which he noted to be a "yellowish" color.

Crops around the river banks reportedly curdled from the contaminated water and sheep that drank the water "keeled over and died." The Rio Puerco, which was integral to Diné herdsmen as a watering hole for their livestock, per American Indian Law Review, suddenly became a death trap. The water level didn't drop until noon, at which point it was possible for people to cross the Puerco again.

A radioactive flood

Although no human died during the flood itself, the water that was released during the flood was incredibly toxic. According to "Killing Our Own" by Harvey Wasserman and Norman Solomon, the floodwater "left residues of radioactive uranium, thorium, radium, and polonium, as well as traces of metals such as cadmium, aluminum, magnesium, manganese, molybdenum, nickel, selenium, sodium, vanadium, zinc, iron, lead, and high concentrations of sulfates."

The water was so toxic that those who went wading in the water ended up burning their feet, writes "Yellow Dirt," leaving them with "blisters and sores" on their legs and feet. Livestock was also said to develop sores and die after the spill due to the water, writes The New York Times, but it was difficult to keep the animals away from the river.

Radiation was detected as far as Sanders, Arizona, which was 50 miles downstream. In total, at least 80 miles of streambeds ended up being contaminated. In Gallup, New Mexico, the water ended up backing up sewers and "lift[ing] manhole covers." The New York Times reports that the alpha count of the river on the first day was found to be 100,000 picocuries per liter. Meanwhile, "the safe drinking water limit is 15 picocuries per liter."

Inadequate messaging and assistance

Although United Nuclear and the Indian Health Service eventually tried to prevent people from drinking the contaminated water or letting their animals drink the water, not only were their efforts inadequate, they actually waited several days before informing people. And when the Indian Health Service and the Environmental Improvement Division of New Mexico finally did put up signs and radio broadcasts alerting residents to avoid the water, a Diné resident from Church Rock noted that many of the written signs were only in English, which "most of us can't read, write, or speak," per "Environmental Justice in New Mexico" by Valerie Rangel. And according to New Energy Economy, Larry King, a former Kerr-McGee employee and anti-nuclear activist with Eastern Navajo Diné Against Uranium Mining (ENDAUM), testified that even the written signs in Diné "served no purpose, as the traditionally spoken language is not a written language" and few people at the time would've been able to read the signs.

United Nuclear gave out around 600 gallon bottles of water after the uranium mill spill, but it was estimated that the Church Rock community needed more than 30,000 gallons a day. Any amount promised by the company was often cut in half by the time it reached people and with no other assistance, people in the region had few other alternatives. Rangel also writes that the U.S. government also reportedly denied the residents' request "for emergency food stamps to replace their lost livestock."

Years of cracks

The breaking of United Nuclear's dam didn't come out of nowhere. United Nuclear was told about the cracking dam almost two years before the dam finally burst. American Indian Law Review writes that in 1977, the beginnings of small cracks in the dam were brought to the attention of United Nuclear by a consulting firm. The consulting firm also mentioned to the corporation the "high settlement rate" and, according to the American Public Health Association, underlined that the dam was built on "geologically unsound land."

And while the dam was in fact a new and improved design, the dam had "special design criteria" that weren't actually followed by United Nuclear during the building of the dam. "Nor did it undertake regular inspections of the completed dam." State and federal agencies also noted during construction that the soil under the dam was "susceptible to extreme settling that was likely to cause cracking and structure failure," similar to the assessment given by United Nuclear's own consultant.

When cracks first started showing up around 1977, they weren't brought to the attention of the relevant authorities. And the Navajo Times reports that just two weeks before the disaster King measured the cracks along the tailings impoundment "that were large enough to put his feet in." According to Nuclear Risks, the dam even had issues with smaller leaks in the past. But the damage caused by the 1979 flood was unlike anything that had ever happened before.

Clean-up response

When United Nuclear realized the breach had occurred around six in the morning, they stopped sending nuclear waste to the dam. After making a temporary wall to hold the floodwaters, the "flow of residual tailings" was stopped by 8 in the morning.

According to the Oversight Hearing on the Mill Tailings Dam Break at Church Rock, although the floodwaters were stopped the subsequent clean up wasn't as successful. Because the clean up "started very slowly," a great deal of radioactive waste was "too badly disseminated to recollect." Rainstorms also spread the radioactive material even more. United Nuclear initially tasked just six to 10 workers to clean the spill and only increased this number to 30-40 people after the Environmental Improvement Division notified United Nuclear that "the clean up was inadequate due to the small number of people participating. By mid-August, contamination had spread past the 75-mile mark.

By October 1979, "only about 0.3% of the total volume of the material spilled [had] been removed from the Rio Puerco." At most, only 1% was cleaned up. And although the New Mexico Environmental Improvement Division ordered United Nuclear to clean up the site in 1983 because of leaking radioactive thorium, United Nuclear responded by filing a lawsuit and challenging their order to clean up their spill in Church Rock, The Washington Post reports. Frank Paul, vice-president of the Navajo Tribal Council, later commented that "UNC was permitted to deal with the spill by doing almost nothing."

Effects of the spill

The total effects of the uranium spill are incalculable. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) found that baseline tests of the river hadn't even been conducted before the spill so it's impossible to know exactly how much radioactive contamination occurred over the years. Several Diné children and adults were sent to the Los Alamos lab and the Indian hospital at Gallup respectively to be examined for radiation exposure. However, "there is no evidence that any long-term monitoring took place" and the effects of radiation exposure would've taken time to show up. One resident noted that "the IHS [Indian Health Service] expended more effort on finding out what happened to the livestock than on finding out what happened to the people."

According to "Yellow Dirt," although a study of Church Rock cattle ended up determining that the health effects of eating livestock that grazed in the area were negligible, researchers stated that this wouldn't pose a problem if the animals weren't depended on for everyday food, which, "of course, is exactly what the Navajos did depend on." The radiation and contamination ended up reaching up to 30 feet into the ground, rendering much of the land toxic as well.

Despite everything, the EPA concluded that the uranium spill of 1979 "had little or no effect on the health of local residents." However, "no long-term community-wide health study was conducted following the tailings spill in 1979," writes the Church Rock Uranium Monitoring Project.

Other instances of radioactive floods

This wasn't the first radioactive spill the United States experienced in the 20th century. American Indian Law Review writes that between 1959 and 1977, there were at least 15 radioactive spills, and seven of them were the result of a failing dam. One incident even involved releasing "35,000 gallons of tailings slurry into the Colorado River."

According to "Mining North America," edited by George Vrtis and John Robert McNeill, the dam failure at the Kerr-McGee uranium mill at Shiprock, New Mexico was also incredibly serious. Releasing up to 780,000 gallons of radioactive waste into the San Juan River on August 22 and 23, 1960, radiation levels of the water spiked to "about 20 times what the USPHS deemed permissible for drinking water." There have also been dam failures at uranium mines in Utah, South Dakota, and Wyoming.

The 1958 Mailuu-Suu tailings dam failure in Kyrgyzstan led to similar devastation as the 1979 Church Rock mill spill. According to Earth Journalism Network, over 400,000 cubic meters of radioactive waste slid into the Mailuu-Suu River in April 1958, spreading almost 20 miles and into Uzbekistan. And the effects of the radioactive spill are still felt over 50 years later, "with the radioactive contamination of the river and surrounding soil and vegetation causing major health problems and fatalities."

Legacy of the uranium spill

Ultimately, the total effects of the 1979 Church Rock uranium mill spill are unknown. The Church Rock Uranium Monitoring Project reported in 2007 that "the long-term effects of past mine-water discharges to the Puerco River, coupled with the onetime shock loading of the stream in the July 1979 tailings spill, remain uncertain." In "Mine Wastes," Bernd Lottermosser writes that even up to 20 years after the spill, uranium contamination of the Rio Puerco was still discernible "as far as [43 miles] downstream from the mines." But unfortunately, it's difficult to discern how much of this was from the uranium mining of the time and how much is from the spill.

For many Diné, the connection between the high cancer rates in the community and the effects of the radioactive mill spill is made easily. Pasternak notes in "Yellow Dirt" that many of the residents in and around Church Rock "suffer from health issues, tumors, and high incidences of cancer." Tony Hood, a driver/interpreter for the Indian Health Service, noticed a "lot of cancer popping up" in his community and considered there to be "no doubt about what – and who – caused the health problems he sees around him," writes the Navajo Times.

And according to Indian Country Today, in 2021, the Navajo Nation continued to call for radioactive waste remnants to be removed while United Nuclear tried to keep one million cubic yards of nuclear mine waste on Navajo Nation trust land.

Toxic abandonment

Although many corporations clamored to get into the nuclear energy business, once the appeal of nuclear power started to fade they were just as eager to jump out of the game. As a result, hundreds of uranium mines were abandoned, with no thought for clean up efforts. Indian Country Today writes that on Navajo Nation trust land, there are over 500 abandoned uranium mine sites. And while there are funds available to clean up over 200 of them, that still leaves 300 uranium mines "that pose severe environmental and health dangers to surrounding areas and people." Some estimates even say that there are actually over 1,000 abandoned mines, per Scientific American.

This oversight wasn't unintentional. According to "Governing the Atom," the U.S. EPA stated in 1983 that abandoned uranium mines on Navajo Nation trust land "were too remote to 'pose a national risk.'" With this statement, thousands of indigenous Americans were relocated to a far-off place where neither U.S. corporations nor the government was responsible for cleaning up after themselves.

AZCentral reports that the estimated price for cleaning the waste from just two uranium mines is expected to cost $131 million. Lillie Lane, Navajo Nation Environmental Protection Agency laments that the process is likely "going to take 100 years." In February 2021, the U.S. EPA awarded contracts to three organizations to assess and clean up approximately 200 abandoned uranium sites, according to The Navajo Nation.