The Surprising Way Charlemagne Still Influences Modern Writing

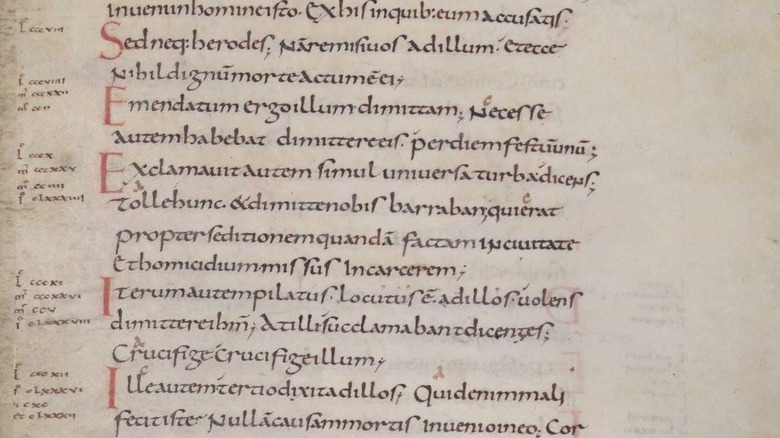

For a second, imagine that this article has no periods. It has no commas, either. It also has no lowercase letters and no spaces between words. There are no consistent margins, no paragraphs, or any way at all to visually distinguish between sentences or topics. Letters also cross over from line to line mid-word. The whole page looks like a kersplatted word-smear pulled from a kindergartener's writing book. Welcome to the written word in "Late Antiquity," the period connecting the decline of the Roman Empire to the "Middle Ages," i.e., medieval Europe (4th – 7th centuries CE, give or take).

The western half of the Roman Empire petered out roundabouts 476 CE, as World History explains, leaving it in charge of Gothic tribes from Poland originally on the run from the Huns in the east. They'd bargained for their migration into Rome and adopted Roman ways, but still held fast to certain "barbarous" aspects of their own culture, like wearing beards.

Emperor Diocletian had done his best to salvage the waning Roman Empire by splitting it into two halves around 285 CE, Western and Eastern. While the Eastern half lived on with Constantinople as its Christianized head, the Western half splintered into regions roughly equivalent to modern Spain, France, and Germany. Europe lived fractured under the shadow of a glorious Roman past.

Into the gap stepped Charlemagne the Frank, the "Father of Europe." Of his many reforms, he overhauled the written word to make it look like, well, this.

Idolizing the Roman past

Charlemagne (late 740s – 814 CE), also called "Charles" in the Anglicized way, or "Charles the Great," had risen to power as the first emperor of the Carolingian dynasty. As World History explains, the Carolingians had wrested power away from the Merovingian dynasty (457-751 CE), who had claimed dominance in western Europe following the decline of the Roman Empire. Charlemagne was the first Carolingian ruler, and even though his sons would squabble enough to diminish his accomplishments, Charlemagne banded together much of western Europe together under one, tenuous rule, as the BBC outlines, and kickstarted the "Carolingian Renaissance."

Charlemagne was responsible for tons of reforms, including standardizing currency and developing the power structures of the Christian church, as Lumen describes. He idolized the Greco-Roman past and wanted folks to learn "real" Latin, not the bastardized Latin (as they considered it) that they spoke, i.e., Old French. As the Metropolitan Museum of Art explains, Charlemagne gathered scholars to his court in Francia, as the region was called, including the English scholar Alcuin, the poet Angilbert, the Spanish theologian Theodulf, and the Italian historian Paul the Lombard.

The job of this crack team? Charlemagne didn't necessarily want to completely change typography but rather create "the most beautiful and accurate copies made of finest existing manuscripts," as Design History puts it. He wanted to demonstrate reverence towards ancient texts. In the process, he would end up overhauling the written word and giving it the form it carries to this very day.

Free public schools from an illiterate man

It's important to say at this point that Charlemagne himself was illiterate. He practiced writing at night, in secret, using "wax tablets he hid under his pillow," as Lumen says, to little avail. Despite this (or maybe because of it), he recognized the importance of reading, writing, and general education not just for the wealthy and his own family, but everyone. He instructed bishops and deacons to set up free "liberal arts" schools for peasants. There, as DargleNotes overviews, anybody at all could learn the rudiments of literacy and Christian doctrine.

Until Charlemagne took over, writing was kept alive by clergy in monasteries for about 300 years following the decline of the Western Roman Empire, as Design History states. Lots of old texts had accumulated little mistakes over time as they'd been copied one by one. Plus, the text itself — all uppercase, no punctuation, no space between words, no standardized margins or shapes of letters — was pretty dang hard to read, especially for a learner like Charlemagne.

This is where the scholar Alcuin of York comes into play. As LucidLit explains, Alcuin got to work in 781 bettering the written word. Two years later in 783, Alcuin had produced the world's first book written in the world's new standardized font, "Carolingian minuscule." It had everything: spaces, punctuation, lowercase letters, proper margins, you name it. This book, the gorgeous Godesalc Evangelistary written in illuminated ink, set the benchmark from then on out.