The Untold Truth About The Gilded Age

As noted by the U. S. Senate, we can thank Mark Twain, the brilliantly wry observer of American life, and his neighbor, essayist, and editor Charles Dudley Warner, for introducing the term "Gilded Age" to the world. "The Gilded Age: A Tale of To-day" was the title of their popular 1873 novel, a satiric examination of the corrupt and decadent politics of contemporary Washington. In the 1870s, America, eager to throw off the sins of the Civil War and celebrate the accomplishments of industrialism, had embraced excesses of all sorts, and the phrase Gilded Age encapsulated perfectly both the power and the shallowness of this trend.

Sources conflict on the dates, but according to History, the Gilded Age began with the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 and ended around 1917, with America's entrance into World War I. For Twain and Warner, the era's essence was embodied in "the young American" for whom "the paths to fortune are innumerable and all open." At the top of the Gilded Age heap were the nouveau riche robber barons, ruthless industrialists like railroad magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt and steel tycoon Andrew Carnegie. As noted by PBS, for women, minorities, the poor, and children, the triumphs of "the young American" were not just unattainable, they were unimaginable. The gilding – the mansions, the balls, the fashion – glittered brightly for the privileged, while underneath, society's foundation could only tread in the darkness.

During the Gilded Age, New York became a divided city

Because it was the economic and cultural center of America, New York City came to epitomize the best and worst of the Gilded Age. According to PBS, after the Civil War, New York's neighborhoods began to shift. The wealthy moved from the shoreline and the south to the city's middle, making Fifth Avenue, from 34th Street to 57th Street, the place for the Protestant rich to live and work. As noted by Fifth Avenue, mansions of such families as the Vanderbilts, the Astors, and the Carnegies popped up all through the area, and construction of luxury hotels and restaurants soon followed. The city's southern section and shoreline, meanwhile, filled up with an influx of newly arrived immigrants. The mostly Catholic and Jewish newcomers worked in the garment and shipping industries and lived in crowded, rundown tenements.

The wealthy's occupation of Fifth Avenue was not haphazard or unconscious. In their foreword to "Fifth Avenue Old and New: 1824 to 1924," leaders of the Fifth Avenue Association, founded in 1907, bragged that their organization's mission was to safeguard the wealthy from "chaos" through a "definite civic program." This "civic program" included forcing the "garment trades" to relocate to Seventh Avenue, denying the building of subway and streetcar lines, and constructing an opulent armory for the National Guard's Seventh Regiment. Nicknamed the "Silk Stocking" Regiment, the volunteer force was expanded in part to protect the wealthy locals against rioting laborers.

Gilded Age mansions were testaments to conspicuous consumption

During the Gilded Age, mansions of the well-to-do sprang up all over America, and as noted by Newsweek, wherever they were located, they were huge. Many were 100 rooms or more, surrounded by hundreds of acres, and built in a European style. Long Island's Harbor Hill, for example, built for a silver magnate's daughter, took up almost 700 acres and was modeled after a French castle, according to Atlas Obscura. George Washington Vanderbilt II's 250-room Biltmore House in North Carolina, the largest mansion in America, was designed in the Châteauesque style, while The Breakers, the Vanderbilts' 70-room Rhode Island "summer cottage," according to Newport Mansions, was built in the Italian Renaissance style. And where there were palatial exteriors, there were also lavish interiors. Gilded Age mansions were not only sumptuously decorated, but many were filled with bona fide art treasures. Not surprisingly, some of them, such as industrialist Henry Clay Frick's Manhattan mansion, ended up as art museums, as noted by Curbed New York.

Of course, being wealthy also meant that personal eccentricities and excesses could be easily indulged. As reported by ABC7 News, the 161-room San Jose estate of the Winchester Rifle heiress boasted a jaw-dropping 10,000 windows, 2,000 doors, and 47 fireplaces. Silver tycoon William Clark's Fifth Avenue mansion not only contained 121 rooms and four art galleries but also housed a private underground rail line for transporting coal to the house.

Nothing was immune from Gilded Age elitism

While housing was an obvious way for the Gilded Age wealthy to separate themselves from the masses, their elitism also expressed itself in more subtle ways. According to History Today, the Metropolitan Opera House was built specifically for the Gilded Age nouveaux riches, after New York's "old money" elites denied them box seats to the Academy of Music. Box seats at the Met were reserved for the newly rich only and were outrageously expensive. According to the New York Herald (via Met Opera Archive), on opening night in 1883, the cheapest seats in the house cost three dollars, a sum well beyond the average opera lover's budget.

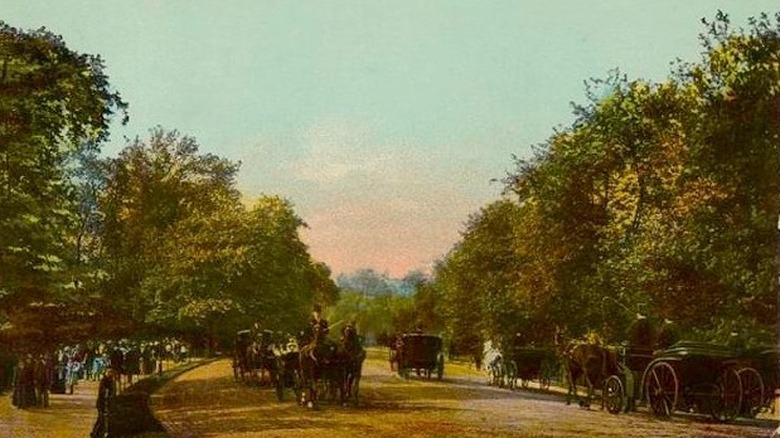

Similarly, New York's Metropolitan Museum was closed on Sundays, the only day working people might be able to take in some culture, according to The New York Times. Central Park, whose construction in the 1850s involved the destruction of Seneca Village, a prosperous Black community, theoretically was open to all, but regulations and hours of operation favored the rich, and to a lesser extent, the middle class, according to BT. Private skating rinks strictly enforced admission rules excluding non-members, for example, and picnicking and drinking were forbidden, making the lower classes feel unwelcome.

Conversely, nickelodeons, the earliest form of commercial movie release, cropped up in the poorest sections of town, and their silent stories catered to immigrants, as noted by PBS. Consequently, the elites poo-pooed them as cheap and frivolous.

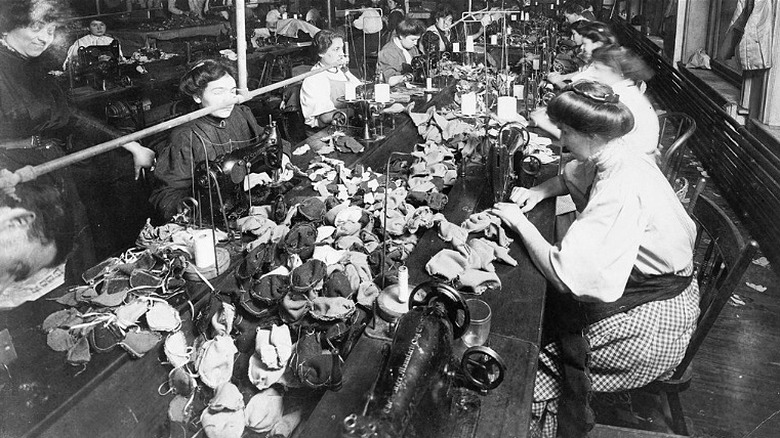

Women worked in menial jobs that paid little

According to Brookings, as the American economy shifted from farms to factories during the late 19th century, women's presence in the workforce grew. But the vast majority of female workers were lower class, young, and single, and the jobs offered to them were usually menial piece work in factories or domestic work. Only a tiny fraction of the young female population attended college or received advanced training. As the Gilded Age went on, more middle-class young women joined the employment ranks, working in clerical, educational, and other non-factory jobs.

However, as noted by "The Making of the Modern U.S.," wherever they worked, women were paid less than men – two-thirds less on average – even when doing the same job. In the West, the most educated female teacher was paid less than a male janitor. According to the Library of Congress, women were paid less because they were thought to be better suited to home life and were not seen as capable breadwinners.

Regardless of their pay and status as single workers, social norms dictated that when women married, they were to quit their jobs and become homemakers. In some cases, laws prevented married women from working. As a consequence, married women, particularly wealthy ones, often looked to charitable work for personal fulfillment. As noted by History, out of the excesses of the Gilded Age came such philanthropic heiresses as Alva Vanderbilt and Louise Carnegie and progressive social activists like Hull House's Jane Addams.

Marriage among the Gilded Age elite was 'complicated'

According to History, during the Gilded Age, America's nouveau riche, eager for social status, would sometimes shop their unmarried daughters among Europe's cashed-strapped aristocratic bachelors. As noted by the Library of Congress, by the period's end, one-third of England's House of Lords had married an American "Dollar Princess." Famous Dollar Princesses included Winston Churchill's mother, the (allegedly) tattooed Jennie Jerome, and Virginia debutante Nancy Langhorne (pictured), who married William Waldorf Astor in 1879 and became the first woman to take a seat in the British Parliament (although she was not the first to be elected).

Although marriage among the wealthy was usually arranged and separation remained the preferred way to deal with infidelity and incompatibility, divorce became somewhat more acceptable during the Gilded Age. According to NPS, Alva Vanderbilt set the change in motion when she insisted on divorcing her philandering husband Willie in 1895, a few years after she had moved to her new mansion in Newport, Rhode Island. Alva was subsequently shunned by her fellows, but as noted by New England History Society, Newport, which had lax divorce laws, soon became the divorce capital of America. Among the elite who divorced there were Alva's daughter Consuelo (who ironically had been forced into a loveless marriage to the Duke of Marlborough by Alva) and Cora Urquhart Brown-Potter, an actress who split from her financier husband when he insisted she retire from the stage. Happily, some of the divorced elite, including Alva and Consuelo, ended up in successful second "love" marriages.

Children were treated like livestock in the Gilded Age

Although child labor was nothing new in America, the number of children in the workplace grew exponentially during the Gilded Age. According to BLS, in 1870, 1 out of 8 children held jobs, and in 1900, more than 1 in 5. Child laborers were picked based both on size and sex, as well as on their family's finances. As noted in VCU, employers sought child workers because they were manageable, cheap, and exploitable. Children took low-skilled jobs inside and outside, doing everything from trash sweeping and newspaper hawking to coal mining and glass blowing. Safety precautions were unheard of, despite the potential dangers of the work. History reports that child laborers under 10 might shuck oysters for 14 hours straight, earn $2 a day cutting cans in a sardine factory, or work barefoot on machinery in textile mills. During the 1870s, young Italian immigrants in New York were forced to become street performers by "padrones," who would steal their earnings and beat them.

In the 1890s, social reformers began agitating for child labor laws, and in 1904, the National Child Labor Committee was formed to tackle the problem. States also pursued reforms, with limited success, and the U.S. Congress passed federal child labor laws in 1916 and 1918. Both laws were struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court, however, and it wasn't until 1924 that a final bill of protection was passed.

From smoking to voting, gilded age women were told no

Beyond work restrictions, during the Gilded Age, laws and social norms limited women's rights in many ways. The most egregious denial, of course, was the right to vote. According to History, while the Suffrage Movement had gained significant influence by the 1870s, it would take decades longer for women to achieve constitutionally guaranteed voting rights. Birth control was also prohibited at this time. Enacted in 1873, the Comstock Act, according to Jurist, made the sale or possession in the U.S. of "Articles of immoral Use," including birth control and information about family planning, a misdemeanor offense. Anti-birth control laws were also enacted at the state level, but reformer Margaret Sanger successfully challenged a New York version of the ban when she opened a birth control clinic in 1916. The federal law remained on the books until 1936, however.

As noted in RD, other activities Gilded Age women were prohibited from, by state laws or convention, were wearing pants, keeping their maiden names, serving on juries, and shopping without an escort. For a brief time, women in New York were prohibited from smoking in public. According to The New York Times, in 1908, a city ordinance was passed making it "against the law for a hotel or restaurant proprietor, or anyone else managing or owning a 'public place' to allow women to smoke in public." Opponents of the ordinance predicted, rightfully, that women would loudly protest the restriction.

Before Facebook, there were women's clubs

According to Women's History, shut out of many pursuits and unable to express their preferences at the ballot box, women started their own political and cultural reform movement during the Gilded Age. The movement began in the late 1860s when journalist Jane "Jennie June" Croly and abolitionist Julia Ward Howe invited women in New York and Boston to form clubs for serious discussions on social issues. These networking clubs proved wildly popular, and new ones soon popped up all across the country. In 1890, the General Federation of Women's Clubs was founded, and by 1910, women's club membership totaled 800,000. Women reformers discovered there was power in numbers, and over time, they were able to compel many progressive legal and social changes, from voting rights to child protection. As noted by the National Women's History Museum, African American women formed their own clubs during the Gilded Age. Ida B. Wells helped formed the first Black women's clubs while speaking against lynching around the country. Along with the topics covered in white clubs, the Black clubs included discussions on racial equality and uplift.

Not all efforts spearheaded by women reformers were progressive. According to VCU, the focus of reformers like Carrie Nation and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union was alcohol prohibition. Over time, the temperance movement attracted a range of disparate supporters, from suffragette Susan B. Anthony to anti-immigrant groups like the Anti-Saloon League. Their efforts paid off when Prohibition became law in 1920.

Racism ran rampant during the Gilded Age

Unlike for whites, the "paths to fortune" for Blacks in the Gilded Age were few and far between. According to History, because of discriminatory "separate but equal" Jim Crow laws, southern Blacks, some former slaves, remained trapped in a cycle of poverty, servitude, and incarceration. Many became sharecroppers, toiling for white landowners for little or no money while racking up inescapable debts. Groups like the Ku Klux Klan closely monitored their movements, and they were routinely attacked, jailed, and lynched. As detailed in National Archives, 1910 marked the beginning of Black America's Great Migration, when southern Blacks exited the South for greater opportunities and freedoms in northern cities like Chicago and New York.

Black women during the Gilded Age faced an additional racist affront, according to PBS. While prominent Black reformers like Mary Church Terrell joined white women in the fight for voting rights, when push came to shove, leading suffragettes like Susan B. Anthony and Carrie Chapman Catt betrayed minority women – Blacks, Asians, and Native Americans – in order to appease Southern whites. In a letter to a Southern white senator, Catt argued for women's voting rights by pointing out that current law technically made white women "subjects" of "negro men," while the 19th amendment would guarantee constitutionally honorable "white supremacy." After the ratification of the 19th amendment, the same tactics used to prevent Black men from voting – poll taxes, literacy tests, violence, etc. – were deployed against Black women.

Gilded Age elites suffered at the hands of doctors

As noted by Slate, between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, overall death rates in America dropped to historic lows. However, death from one cause – childbirth – increased during this time, and blame for the increase came down to one factor – physicians. Wealthier pregnant women were tended to by doctors (almost exclusively male) out of the belief that doctors would provide higher quality care than midwives, but their childbirth death rate was actually higher than it was for poor women. Unlike midwives, doctors used forceps and other instruments during labor but didn't take care to sanitize them, and they performed procedures like Cesarean sections without proper precautions. Consequently, many well-to-do women died during labor from blood loss or suffered deadly postpartum infections.

Physicians also unleashed "Rest and West Cures" on Gilded Age elites. According to APA, in 1869, neurologist George Beard advanced a theory that "neurasthenia" – depression, anxiety, migraines, and other related complaints – occurred when culturally superior Americans overtaxed their brain and nervous systems. Based on Beard's theory, doctors treating wealthier patients for "neurasthenia" would prescribe prolonged breaks and radical changes to everyday routines. For a depressed woman, treatment might include electrotherapy, massages, red meat, remaining housebound for weeks, and not engaging the mind in any creative or intellectual thought. Men, on the other hand, would be advised to enjoy rigorous physical activity out West, then use their creativity and write about their experiences.

The Gilded Age gave birth to Social Darwinism and eugenics

Running in tandem with its great disparities in wealth and opportunity, the Gilded Age was also marked by the emergence of extreme political and cultural movements. As noted by Britannica, social Darwinism, or social "survival of the fittest," grew into a significant economic and social philosophy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Led in America by sociologist and economist William Graham Sumner, social Darwinists argued that practicing "natural selection" in the social sphere would result in a positive culling among the various classes. To activate the competition, Sumner and others advocated for conservative, anti-welfare social policies, deeming poor people as "unfit" for assistance, and laissez-faire economic policies, which favored the rich and powerful.

According to History, the Gilded Age also gave birth to social Darwinism's cousin, eugenics, a scientific practice whose aim was to improve the human species and reduce suffering through selective mating. Initially promoted in England by Charles Darwin's actual cousin, Sir Francis Galton, eugenics first reared its head in America in 1896, when marriage laws in Connecticut prohibited epileptics and other "feeble-minded" adults from marrying. Additional discriminatory marriage laws soon followed, and in 1903, the American Breeder's Association was formed to promote the study of human eugenics. In 1911, John Harvey Kellogg, the "cereal king," created a eugenics-inspired "pedigree registry" and launched the Race Betterment Foundation.