Messed Up Things That Happened During The Lincoln County War

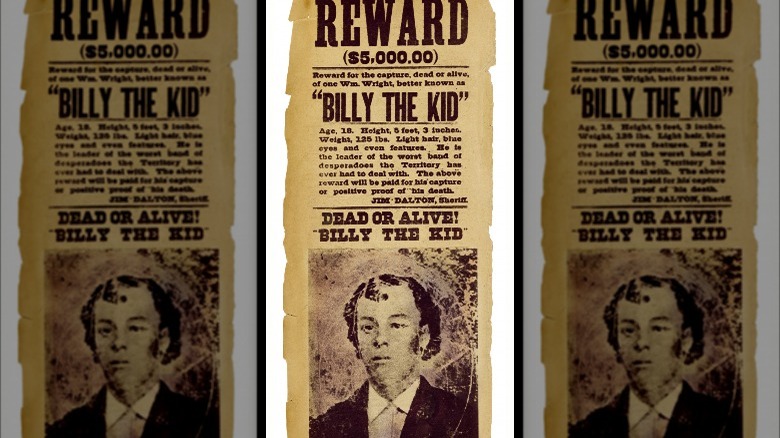

The Lincoln County War of 1878 shocked the nation and catapulted to infamy America's ultimate bad boy, the bowler-hat, sweater-wearing gunslinger, Billy the Kid. It shed light on the corruption lurking beneath the surface in New Mexico Territory, and it spawned countless historical investigations, books, and movies, including the "Young Guns" series starring Emilio Estevez.

The conflict represented a high-stakes Monopoly game for regional dominance, and both sides resorted to lethal force. Two Irish immigrants, Lawrence G. Murphy and Jimmy Dolan, controlled much of the commerce in Lincoln as well as its economy (via Legends of America). According to the Ruidoso News, people referred to the Murphy-Dolan enterprise as "The House." Their captive audience included the impoverished and wealthy alike. Only one man could challenge their rule, the cattle king John Chisum, as reported by History.

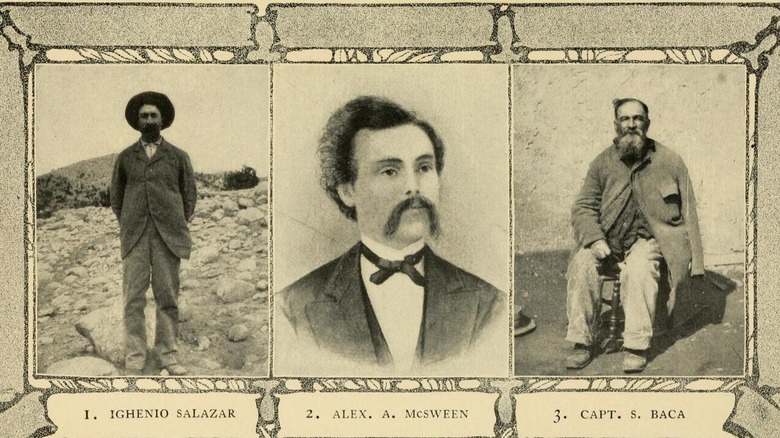

But everything turned upside down when John Tunstall, an ambitious English national, arrived on the scene determined to capture some of the business in Lincoln County. To add insult to injury, he recruited one of Murphy and Dolan's former attorneys, Alexander McSween, to partner with him, per Legends of America. The objective? To legally harass the Murphy-Dolan faction and wrest power and business from their mighty grip. It didn't take long for open hostilities to break out, and a teenager named William Bonney (aka Billy the Kid) rose to national fame in the flameout. Here's what you need to know about the messed up things that happened during the Lincoln County War.

Each side gathered a small army to wage war

As tensions ratcheted up in Lincoln County, the community became polarized. According to "Billy the Kid: A Short & Violent Life," by Robert M. Utley, the Dolan-Murphy faction proved cunning and unscrupulous. As a precaution, John Tunstall hired "ranch hands" with gunfighting skills, per History. Yet, Tunstall underestimated his enemies, argues PBS. Although he and Alexander McSween benefited from the sympathies of small-scale Hispanic ranchers and farmers, Murphy-Dolan tyranny proved an intractable force, writes Michael Wallis in "Billy the Kid."

That said, Tunstall's ranch hands represented the core of the "army." When Tunstall was murdered by House supporter William Morton in 1878, these deputized men exacted vengeance as the Lincoln County Regulators. A then-teenaged William Bonney, who gained notoriety using alias Billy the Kid, was part of the group. While the Tunstall-McSween crew fortified their defenses, the Murphy-Dolan faction went on the warpath.

Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan enjoyed support at the highest levels, including the Lincoln County Sheriff William J. Brady (via History Ireland). A friend and former army colleague of Murphy, Brady also hailed from Ireland and owed a considerable sum of money to Murphy, which placed him squarely in the pocket of "The House." As for hired guns, Murphy and Dolan enlisted members of the Jesse Evans Gang, reported by Legends of America, which Brady deputized to go after Tunstall.

Violence exploded with the murder of John Tunstall

Just one spark would engulf Lincoln County in the flames of war, but locals didn't know where that incendiary would originate. It came in the form of the murder, whether cold-blooded or in self-defense, of 24-year-old John Tunstall on February 18, 1878, according to Robert M. Utley's "High Noon in Lincoln: Violence on the Western Frontier." Because the gunmen pursuing Tunstall separated him from his ranch hands, no eyewitness accounts exist about what happened next apart from the dubious testimony of Tunstall's murderers, according to the Ruidoso News.

Legends of America reports the Murphy-Dolan faction sent out a large posse to seize horses from Tunstall, which he refused to surrender to settle a debt. While protesting the gang's presence on his land, the shooting began. Members of the gang quickly dispatched Tunstall with a shot to the chest and one to the head. Next, they gunned down Tunstall's horse adding insult to injury. (Tunstall's love of equines was well known in the county.)

But the barbarity didn't end there. "The Boys," as many called the Jesse Evans gang, positioned Tunstall's body with his horse to look as if they napped together, The Ruidoso News reports. Tunstall's murder devastated his men, especially Billy the Kid, who swore, "I'll get every son-of-a-bitch who helped kill John if it's the last thing I do" (via Legends of America).

The shadowy Santa Fe Ring orchestrated the whole thing

It's difficult to comprehend the corruption driving the Lincoln County War without knowledge of the power network ruling New Mexico Territory (via the Santa Fe New Mexican). Known as the Santa Fe Ring, their greed knew no bounds. Especially after they gained the support and influence of two federally appointed attorneys, Stephen B. Elkins and Thomas Benton Catron.

From this power core, "circles of influence kind of radiated outward," according to Historian David L. Caffey in an interview with the Santa Fe New Mexican. Comprised chiefly of Euro-Americans recently transplanted to the territory, the Ring also found support among a handful of Hispanic ranchers and business owners with shared interests. The Ring included retailers, lawyers, ranchers, politicians, and military officers, all with a bent for wresting and maintaining control of the territory.

Think of them as the carpetbaggers of the Southwest or the insipid metallic glint on what Mark Twain sardonically termed the "Gilded Age," as described by the Santa Fe New Mexican. They saw the chance to exploit muddled land ownership records in the New Mexico territory. After all, many of the original land allotted to Hispanics in the area came by way of handshakes rather than written documentation. The Ring exploited this reality to seize countless rancheros because of a lack of ownership paperwork.

U.S. Deputy Marshalls played both sides of the conflict

Legends of America reports that Billy the Kid's vow of vengeance had to wait because Sheriff William Brady immediately jailed him. He remained in detention through John Tunstall's funeral. After release, Billy joined the posse headed by Tunstall's friend and U.S. Deputy Marshal Robert Widenmann, per History Net. As deputy marshal, Widenmann had the power to deputize the men who rode with him, providing them with the (false) assurance they operated within the law.

In a letter from John E. Sherman Jr., the U.S. marshal for the entire territory, to Col. Edward Hatch, head of the military district of New Mexico, Sherman demanded three companies of soldiers to accompany Widenmann's posse in their pursuit of justice. What's more, an unsigned deposition by Atanacio Martinez, Lincoln County deputy, declared Widenmann's posse, including Billy the Kid, federally deputized actors. Nonetheless, backup troops never arrived.

The same day Widenmann's posse apprehended some of "The Boys," Gov. Samuel Axtell revoked Widenmann's deputy marshal status. The corrupt politician's clever act muddied the legal waters. In the chaos, several of "The Boys" died, including Tunstall's murderer, William Morton, executed by Billy the Kid. Although the Regulators saw themselves as the long arms of the law, plenty of Lincoln elites disagreed. After all, the Murphy-Dolan crew's ace remained Brady, and he wouldn't let the deaths of his deputies go unpunished.

Law enforcement wasn't immune to the violence

At 9:30 a.m. on Monday, April 1, gunshots rang out in the streets of Lincoln, per Frederick W. Nolan's "The Lincoln County War: A Documentary History." Sheriff William J. Brady lay assassinated along with one of his deputies, George Hindman. Gunned down without warning, Brady's body looked like gory Swiss cheese, nine bullet holes peppering his core. As for Hindman, death took longer. He staggered a few feet before hitting the ground.

Juan Peppin, the oldest son of Brady's deputy, George Peppin, reported hearing gunshots from town but didn't initially think much of it. His father later told him that the Regulators had carefully laid a trap for Brady and his men, alleging that the Tunstall-McSween crew snuck into Lincoln in the middle of the night, holding up in the corral. Juan Peppin said his father claimed, "They had drilled port holes in the east wall of the corral, so they could level their rifles through them." In other words, Brady never stood a chance.

But supporters of the Tunstall-McSween side told a different story. Dr. Taylor F. Ealy referred to Brady and his deputies as "a dirty set of Irish cut throats." His account of events never mentions the Regulators sneaking into town at night or drilling port holes. Instead, he stated that Brady met his end while attempting to enter a house with several businesses inside, which Legends of America reported to be John Tunstall's store.

Things got so bad the President of the United States intervened

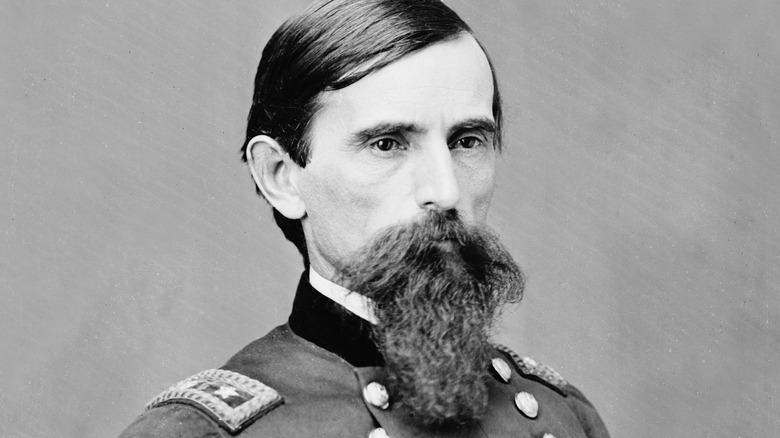

By September 1878, Lincoln County's scandals reached the nation's capital, and President Rutherford B. Hayes intervened (via Legends of America). To clean up the rampant corruption, he forced Gov. Samuel Axtell out of office, replacing him with Civil War veteran Lew Wallace.

Despite Wallace's vaunted background and presidential support, he faced a difficult road. In a letter to a friend, he lamented, "I came here, and found a 'Ring' with a hand on the throat of the Territory. I refused to join them, and now they are proposing to fight me in the Senate," per the Santa Fe New Mexican. Loosening the vise-like grip of the Ring — a group of powerful and corrupt political and economic leaders — on Lincoln County appeared futile, even to Wallace. He appointed Eugene Fiske to the office of attorney general. But the Ring disapproved. They'd long controlled the office and weren't about to let it go. So, they supplanted Fiske with William Breeden, a loyal follower.

Robert Utley claims in his book, "High Noon in Lincoln: Violence on the Western Frontier," that Wallace proved ineffective. Instead of fighting corruption head-on and protecting vulnerable citizens, he retreated into escapism via creative writing. His nightly hobby yielded the novel "Ben-Hur." Although a literary masterpiece, it did little to remedy the injustices facing small farmers and ranchers caught in the crosshairs of the Lincoln County War.

'The House' flew the black flag of no quarter

The death of Alexander McSween on July 19, 1878, should've marked the conclusion of the Lincoln County War, according to Robert Utley's "High Noon in Lincoln: Violence on the Western Frontier."

The incident culminated with the reinforcement of Col. Nathan Dudley and his troops from Fort Stanton with a Howitzer cannon and Gatling gun, as per "The Lincoln County War," by Frederick W. Nolan. George Peppin, appointed sheriff after William Brady's murder, gathered reinforcements, as well, to take now the Regulators. The soldiers lit the McSween house on fire and picked off its male occupants as they attempted to flee the inferno (via Legends of America). McSween's wife, Susan, described her husband's death: "In the evening my husband and his friends blinded by smoke weried [sic] by battling the flames and the no less remorseless enemies outside driven from room to room as the fire increased till the last room was consumed at last sallied from the home and ... was shot down like a dog on his own threshold when he had fallen upon his knees calling out I surrender ..." McSween was unarmed.

Before McSween's execution, the Murphy-Dolan faction flew an ominous black flag. The message proved unmistakable. They would offer no quarter to the enemies of "The House." Even if it meant gunning down defenseless people as they attempted to escape a burning house.

Providing legal representation could be lethal

Following her husband's shooting death, Susan McSween hired attorney Huston Chapman, according to Legends of America. McSween sought justice for the murder of her husband. She demanded Sheriff George Peppin and Col. Nathan Dudley be held accountable for arson and homicide, per True West. The lawyer fought vigorously on her behalf.

Chapman had an ace up his sleeve, although it never got played. Dudley had violated the secretary of war's direct order and the Posse Comitatus Act, which prevents the executive branch from using the military domestically as law enforcement, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. But Chapman's enthusiastic pursuit of the rule of law didn't go unpunished. At 10:30 p.m. on February 18, 1879, Chapman accidentally bumped into Jimmy Dolan and members of his crew. The men had saloon-hopped all afternoon, working themselves into an inebriated stupor. They demanded Chapman dance a jig, which he refused to do.

In retaliation, Billy Campbell pressed a gun into the attorney's chest and fired, sending him reeling backwards with his clothes aflame from the gunpowder flash. Dolan followed up with a second shot from his Winchester. As Chapman breathed his last breaths, exclaiming, "My God, I am killed," Campbell admitted murdering Chapman as a favor to Dudley. Although Gov. Lew Wallace and the citizens of Lincoln felt shocked and outraged by the cold-blooded murder, Dolan's corrupt ties yet again shielded "The House" from prosecution.

A failed amnesty and an unfulfilled pardon

One of Lew Wallace's primary objectives after his appointment was to bring the violence in Lincoln County to a standstill. As per Legends of America, the newly appointed governor weighed his options, including calling martial law. In November 1878, he opted for an amnesty that applied to everyone involved in the Lincoln County War, except for Billy the Kid and individuals already under indictment.

But the amnesty did get Billy the Kid's attention, according to the PBS. The young gunslinger penned a letter to Wallace, asking for inclusion in the amnesty and pointing out that he hadn't picked up a weapon since hearing about it.

Wallace saw an opportunity in the Kid's letter and replied with an offer of a pardon if the outlaw would testify in court. The next month, he appeared before a grand jury. His testimony led to many criminal counts against individuals involved in the war. The Kid fulfilled his part of the bargain to a tee. But Wallace ghosted him. In return for the young man's bravery, Wallace took out an ad in the newspaper in December 1880 offering a $500 bounty for the capture of Billy the Kid.

The press found a scapegoat in Billy the Kid

While the Dolan-Murphy faction largely escaped the justice dealt the Regulators, the smell of corruption lingered in the Lincoln County air. According to Marc Simmons' "Stalking Billy the Kid: Brief Sketches of a Short Life," everyone from the governor to the sheriff needed someone to blame for the violence, and young William Bonney presented the ideal target. After all, yellow journalists and dime novelists had already spun legendary narratives about the crack shot teenager — his passionate vow to avenge the death of John Tunstall provided the motive.

As True West argues, "The Santa Fe Ring, Tom Catron, Jimmy Dolan and all the rest needed a convenient scapegoat to shift the public focus from their nefarious deeds and Billy would be the chosen one." Of all the men involved in the Lincoln County War, only one man stood trial for any crimes, Billy the Kid. Many of the other Regulators ended up in coffins or on the lam before indictments got dealt.

The media circus, coupled with Gov. Lew Wallace's double-crossing, put Billy the Kid in an impossible situation. With most of his allies dead, the Kid fled protective custody to hide out in New Mexico.

The Kid's court trial proved a mockery of justice

Billy the Kid's testimony resulted in the Dolan-Murphy crew facing more than 250 criminal indictments, per True West. But their crony connections ensured all parties got off scot-free. With the monopoly holders victorious and free from competitors John Tunstall and Alexander McSween, the total weight of the law came down on the Regulators. Or, more specifically, the youngest member of the group, Billy the Kid, who was apprehended by Sheriff Pat Garrett in order to stand trial for the murder of William Brady. Ironically, the only man to cooperate with New Mexico's authorities, he would also be the only one to stand trial (via True West).

Betrayed by the governor and pardon-less, Billy the Kid's court trial appeared to seal his fate. The media had already tried and convicted him in the court of public opinion, painting him as one of the most ruthless banditos this side of the Rio Grande.

According to History, the judge presiding over his case, Warren Bristol, took great zeal in sentencing Billy the Kid to death, proclaiming, "You are dead, dead, dead." To this, the hardened teen gunslinger replied cheekily, "And you can go to hell, hell, hell." The Kid's conviction set the stage for one of the most famous jail breaks in history, when he singlehandedly killed two armed guards and fled from the jail in Lincoln, New Mexico, narrowly avoiding the noose.

The Lincoln County War ended with Billy the Kid's murder

In 1880, Pat Garrett ran for sheriff of Lincoln County on an anti-corruption platform, per Legends of America. At the top of his agenda was the capture of Billy the Kid. Although this platform endeared him to the powers-that-be, it raised suspicion among the common people who still longed for a savior to deliver them from the clutches of "The House." Many of these small-time Mexican-American agriculturalists saw Billy the Kid as that savior, as reported by Today.

Garrett, like Sheriff William Brady before him, won his election with the expectation that he would tow the Murphy-Dolan line. This sealed the fate of the remaining Regulators, most specifically, Billy the Kid. Ironically, Garrett and the Kid knew each other well, having socialized in Fort Sumner (via History Net). But their former acquaintance didn't stop Garrett from gunning the Kid down in the middle of the night. His murder, ruled justified homicide, brought the Lincoln County War to an end.

In his book, "The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid," Pat F. Garrett describes gunning down the Kid in a darkened bedroom. According to his account, the fugitive he'd sought so long never said a word and only gasped a little before expiring. Although the elites would applaud Garrett's success, Lincoln County's small farmers and ranchers mourned William Bonney's death, which marked the official end of John Tunstall's attempt to dethrone "The House."