The Real Reason The 1930s Were Considered 'The Golden Age Of Radio'

While it's been widely contested who actually invented the first radio (both Italian physicist Gugliemo Marconi and Serbian-American inventor and engineer Nikola Tesla were fighting for the first patent, per PBS), it was Marconi who came out top in 1904, when the U.S. Patent Office officially dubbed him the inventor of the new breakthrough technology. According to APM Reports, in 1920, Americans had their first commercially licensed radio station in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: KDKA. That number quickly rose after KDKA broadcast the election that saw Warren G. Harding become the 29th president, and by 1924, 500 stations were available for listening.

By 1930, over "40% of American households owned a radio," per APM Reports. This became known as "The Golden Age of Radio." As revealed by PBS, in 1930, 12 million Americans owned radios — growing to a whopping 28 million by the end of the decade.

Access to the radio came at a turbulent time in history. As the Great Depression caused widespread suffering for millions of Americans (via History), the households that could afford a radio saw it as a welcome source of entertainment and news that made them feel connected to the rest of the country. These days, with over 15,445 radio stations available in the U.S., it's clear the radio still remains relevant, but its impact on society truly began nine decades ago. Let's take a look at the real reason the 1930s were considered "The Golden Age of Radio."

The concept of the soap opera was born

These days, it's pretty common to see cinephiles and TV fanatics bash daytime soap operas. James Franco, who once appeared on "General Hospital," elaborated on this concept in an essay for Lapham's Quarterly (via The Week), citing the "melodramatic plotlines, constant exposition, unnatural lighting, swelling music, and lack of action." Interestingly enough, soap operas have been around for decades, and the familiarity of them keeps fans coming back for more.

It turns out soap operas got their start during The Golden Age of Radio. According to Classic FM, the term was coined thanks to the soap commercials that would play — the perfect sponsors for the target audience of these radio dramas. As explained by the Old Time Radio Catalog, because children were at school and men were working, the housewife was the primary consumer during these hours, as the radio was her perfect companion while there were chores to be done.

As the Library of Congress highlights, writers Anne Hummert, Irna Phillips, and Elaine Sterne Carrington are credited for spearheading the development of soap operas, with Phillips, in particular, being a "pioneer" responsible for many elements of the soap that are still common today, such as "cliffhangers, organ-music bridges between scenes, and characters appearing concurrently in different serials." In fact, Phillips' legendary soap, "The Guiding Light," is known to be the "longest running broadcast drama," having successfully transitioned to television in 1952 (after 15 years of radio) and ending in 2009 (via Old Time Radio Catalog).

Cooking with the radio

For the 1930s housewife that wasn't interested in melodramatic radio soap operas, she thankfully had another option: cooking programs. According to The Austin Chronicle, Betty Crocker was the first to have her own radio cooking show, "The Betty Crocker Cooking School of the Air," premiering in Minnesota in 1924, going nationwide two years later, and remarkably, lasting "for almost a quarter-century." As it turned out, Betty Crocker wasn't actually a real person: the personality was created by advertising executives, which saw 13 different actors portray the role throughout its long-lasting airtime.

However, Betty Crocker wasn't the only cooking guru for Americans. As revealed by the Old Time Radio Catalog, nutritionist and chef Erma Perham Proetz launched "The Mary Lee Taylor Program" in 1933, working under the pseudonym of the eponymous character. At the time, Proetz was an advertising executive for the Gardner Advertising Company, and launching their program at the height of the Great Depression meant that the recipes shared during the 15-minute segments were "easy [and] economical," while featuring Gardner's star sponsor: PET Milk.

According to the company's website, PET's brand of evaporated milk rose to prominence during World War I, yet again becoming a staple during the Depression. "The Mary Lee Taylor Program" was a massive success, becoming the "longest running radio cooking show," which lasted until 1954 (via Old Time Radio Catalog). Proetz saw praise for the creation, and in 1935, "Fortune Magazine named her as one of the 16 outstanding women in American business" (via American Advertising Federation).

Children had their own programs

Besides homemakers, children were also huge consumer targets for daytime radio programs, getting lost in the adventures of pop culture icons such as "Little Orphan Annie" and "Flash Gordon," per Britannica. Interestingly enough, both of these characters started off as comic book personalities. As noted by Radio World, the "Flash Gordon" comic strip launched in 1934 as a competitor to fellow sci-fi comic, "Buck Rogers." The following year, "The Amazing Interplanetary Adventures of Flash Gordon" made its radio debut, sticking closely to the strip's plot as a "week-by-week adaptation."

"Little Orphan Annie," on the other hand, was already popular with her 1930 radio debut, considering the strip launched in 1924, per National Women's History Museum. "Little Orphan Annie" was revolutionary for multiple reasons. First of all, it has the distinction of "becoming the first nationally broadcast children's program with a child as the main character." If that's not all, the beloved heroine broke gender stereotypes of the 1930s, becoming a fantastic role model in a sea of "male-dominated" leads.

Of course, much like how PET milk sponsored "The Mary Lee Taylor Program" for homemakers, "Little Orphan Annie" had the Ovaltine company. Listeners would collect Ovaltine's "box tops or labels" and mail them in with the incentive of receiving toys as a result — all Ovaltine-branded premiums. Of course, after competitors saw the advertising success that Ovaltine had with "Little Orphan Annie," many copied the same model with other radio shows (via National Women's History Museum).

Popular programs 'promoted old-fashioned American family values'

The Great Depression didn't only affect the American public economically; it also brought turbulence to family dynamics within the everyday home (via History). According to Encyclopedia.com, the "traditional" concept of men being the sole breadwinners of the household was challenged as unemployment rates soared in the early '30s. As husbands suddenly saw themselves spending much more time at home and experiencing the "humiliating" notion of applying for government aid, squabbles with their wives became much more of an everyday occurrence, and, as such, divorce rates rose.

Sadly, as explained by Encyclopedia.com, youngsters from these turbulent homes "often remembered their fathers as emotionally distant and indifferent," while others saw their fathers drinking much more frequently. The radio played an important role in trying to reverse this troubling family dynamic. Per PBS, popular radio shows with heroes such as "The Lone Ranger" and "The Shadow" made a point to "[promote] old-fashioned American family values," in turn, reminding the public what was truly important.

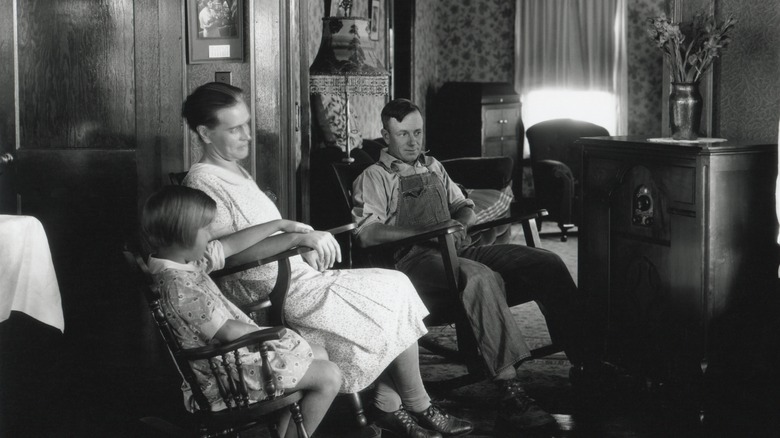

Considering millions of Americans owned radios in the 1930s, the concept of sitting together as a family and listening to a popular program enlisted a sense of "togetherness and solidarity," per Encyclopedia.com — not to mention that it was a free form of entertainment for those that couldn't afford much more.

It was considered 'the internet of the 1930s'

There's no denying that the invention of the radio paved the way for future modes of communication, such as the television and internet, making revolutionary steps to ensure people felt connected around the world. By the end of the 1930s, almost an incredible 90% of Americans owned radios — that's more than how many owned cars or had indoor plumbing, notes historian Bruce Lenthall (via History).

Yet, much like some of the initial hesitation that came with the introduction of the internet in the 1990s, not everyone was exactly welcoming to this relatively new mode of rapid communication. Journalist Anne O'Hare McCormick wrote about the radio in The New York Times in 1932, dubbing it a "great unknown force" (via APM Reports), going on to say that the experience of listening to the little machine had a "dazing, almost anesthetic effect upon the mind." While McCormick eventually praised the radio for its ability to bring families together, another doubter, scholar Jason Loviglio, warned audiences to absorb information with a grain of salt so as not to become influenced by "irrational forces" such as "communism" or even "bankrupt capitalism."

Nevertheless, as APM Reports puts it, the radio truly was "the internet of the 1930s," developing what was even looked at as a "godlike presence" with its ability to reach an entire country, regardless of geographic and economic location (via History).

News programs revolutionized how the public consumed current affairs

Although the first national news broadcast premiered in 1920, The Golden Age of Radio truly revolutionized how the public consumed current affairs in real-time. According to We Are Broadcasters, in 1932, famous aviator Charles Lindbergh had his 20-month-old baby, Charles, kidnapped — with radio stations dubbing it the "Crime of the Century." It was actually thanks to the radio's "detailed description" of the missing child that helped find Charles' remains. According to Biography, the subsequent trial saw radio reporters providing "endless commentary and updates" — the first example of the public's obsession with true crime that's still relevant today.

Another noteworthy moment in journalism during The Golden Age of Radio was Herb Morrison's eyewitness report of the Hindenburg disaster in 1937. As detailed by The National Archives, it was "one of the most famous broadcasts in the history of radio journalism," with Morrison chillingly describing the exact moment that the transatlantic passenger airship burst into flames. "There's smoke, and there's flames, now, and the frame is crashing to the ground," Morrison detailed on Chicago radio station WLS, adding, "Oh, the humanity, and all the passengers screaming around here!"

By the end of The Golden Age of Radio, radio journalism evolved to the point that it didn't just report on events as they were happening. According to the Smithsonian Institute, this evolved into "interviews, panel discussions, and documentaries," too.

Franklin D. Roosevelt's 'fireside chats'

By the time Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected into office in 1933, the United States had already been suffering through the Great Depression, which began with the stock market crash in 1929. Roosevelt found himself in the middle of a crisis; according to History, 1933 was the "lowest point" of the economic downturn, with approximately 15 million people jobless and "thousands of banks" having been shut down.

Thankfully, FDR had a plan to calm widespread hysteria. On Inauguration Day, March 4, 1933, the newly-elected president famously told the public, "the only thing we have to fear is fear itself" (via History). His calm demeanor only grew as time went on — thanks, in part, to The Golden Age of Radio. Along with launching the revolutionary New Deal as a means to jumpstart the economy, FDR knew he had to connect with his fellow Americans. According to History, on March 12, Roosevelt gave his first "informal" speech over the radio, which was broadcast across the country, addressing the banking crisis while applauding the public's "fortitude and good temper."

FDR delivered 30 more speeches between 1933 and 1944, which would be named his "fireside chats." According to PBS, these "chats" bolstered confidence amongst the masses, helping "the population feel closer to their president than ever," and in turn, providing a sense of comfort that people so desperately needed.

Frenzy over The War of the Worlds

British author H. G. Wells first published his now-legendary science fiction novel, "The War of the Worlds," in 1897. According to Britannica, the story sees a "falling star" crashing into England and the subsequent bloodshed between humans and "Martians" — now considered a landmark sci-fi tale.

Fast-forward to October 30, 1938, when director and screenwriter Orson Welles broadcast an adaptation of "The War of the Worlds" on his "Mercury Theatre on the Air" radio program. A clever Welles decided to tweak the story, turning it "into fake news bulletins describing a Martian invasion of New Jersey," per Smithsonian Magazine. The result? Mass panic throughout the country, and the following morning, on Halloween day, Welles was "the most talked-about man in America," with newspapers all over the country detailing his broadcast. "If I'd planned to wreck my career, I couldn't have gone about it better," the star told reporters at the time (via Smithsonian). Sure enough, people were furious, and Welles described hearing "reports of mass stampedes, of suicides, and of angered listeners threatening to shoot him on sight."

While the hysteria has gone on to cement itself as an iconic pop-culture moment of the late '30s, some say that the press exaggerated the entire ordeal. According to "Getting It Wrong: Debunking the Greatest Myths in American Journalism," while the radio program certainly spooked some folks, it's alleged that the majority understood it as a Halloween prank and that the reports were "entirely anecdotal."

Music during The Golden Age of Radio

Of course, much like today, music was immensely popular during The Golden Age of Radio. As explained by the University of Virginia, the Great Depression saw the closure of nightclubs — meaning Americans didn't have many places to turn to for musical entertainment. As such, music programs on the radio (for those who could afford to own one) flourished.

Big bands and swing music were trendy in the 1930s, before the rise of solo singers such as Frank Sinatra in the 1940s. According to Britannica, this included acts led by Artie Shaw, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey, among others. On the opposite end of the sonic spectrum, NBC launched their "Symphony on Air" in 1937, a weekly orchestral radio program led by famed conductor Arturo Toscanini. Per Britannica, these concerts weren't just broadcast nationally; the New York-based program was listened to globally. "Symphony on Air" boosted Toscanini to "mythic status" (via OpenEdition Journals), and he remained with NBC until his retirement in 1954.

Meanwhile, overseas, "dance band music and hot jazz" was the most popular in Britain — something that changed with the start of World War II at the end of the decade. During this time, the BBC began broadcasting "Music while you Work" over factory loudspeakers as a means to "[boost] morale and [keep] the industry running" (via National Museums Liverpool).

When did The Golden Age of Radio end?

The start of World War II in 1939 marked the end of The Golden Age of Radio, or, at least, the sheer volume of family-friendly content such as children's shows and radio soap operas. As explained by DPLA, after Adolf Hitler invaded Poland in September, families in America gathered around the radio to hear "wartime news in real time," as France and Britain declared war on Germany. Of course, this was the first time families could tune in as such a monumental disaster was happening, and as the years went on, the war engulfed radio news networks across the country, relying on "major networks' overseas correspondents," per Britannica.

Although radio news stations were already something the public was used to thanks to other current events throughout the 1930s, World War II truly allowed these broadcasts to take center stage and evolve. According to Britannica, notable journalists of the era even traveled overseas to cover the war, such as Edward R. Murrow of CBS. With the help of fellow reporter William L. Shirer, the pair were stationed in London (which eventually grew to be an entire team of journalists) and broadcasted to the U.S., becoming known for their signature opening line, "This ... is London."

Back home, stations didn't merely cover the events across the pond. As detailed by Britannica, some programs solely existed to maintain the public's morale, while others were "used for propaganda purposes."

The Golden Age of Radio began to fade with the rise of the television

There's no doubt the radio left a significant impact on society and pop culture today, but as corporations produced new technologies, the glitz of the radio started to fade. As it turns out, one of the biggest companies that helped push the success of the radio to the masses, RCA, was also responsible for making the television just as popular — a technology that "had been in development since the late 1920s" (via DPLA).

In April 1939, Franklin D. Roosevelt appeared on television for the first time at the World's Fair in New York — becoming the first American president to do so. Although the broadcast was only seen on the few home TV sets in New York and the mechanics were "primitive," there's no doubt that the combination of visuals and sound engulfed audiences. According to DPLA, these early television broadcasts were a mere 15 minutes long, give or take, and only required one camera to film.

Sadly, television didn't evolve as quickly as the public would have liked. The start of World War II halted the development of various technologies and experimentations, leaving "only a few thousand" homes with television sets before 1947, as noted by DPLA. By the late '40s and '50s, many top radio shows transitioned to television, while TV sets themselves replaced the central presence of "furniture-like radios" in living rooms across the country. Just like that, The Golden Age of Radio came to a close (via Economic History Association).