The Aztec Pantheon Of Gods Explained

As explained in "The Aztec Templo Mayor Symposium," the Aztecs had a very specific way of understanding the world. The essence of this cosmovisión, as we call it today, is in relations between people, nature, celestial bodies, gods, and other invisible realms. They pictured the world through horizontal and vertical planes, expanding far out into the universe — the point where these planes meet, "the navel" of the world, is the center of the universe and our existence. The horizontal plane separates in four directions: south, north, west, and east. The vertical plane has the earth dimension, but also consists of 13 heavens upwards, and nine levels of the underworld downwards. This structure played an important part in everything, from how the Aztecs were thinking to how they built their cities. Both the ancient land Aztlán, as well as the succeeding city Tenochtitlan, were built in accordance with this concept.

Even time becomes extremely complicated with the Aztecs, since they believed that this world that we live in is not the first to exist. There were four worlds prior to ours, according to "Aztec and Maya Myths," and each had its own deity, god, and corresponding element (earth, fire, wind, and water). The gods from the Aztec pantheon were born in different suns (worlds) and on different planes, so their family relations and those with humans are more intertwined than a ball of yarn.

Here is the Aztec pantheon of gods explained.

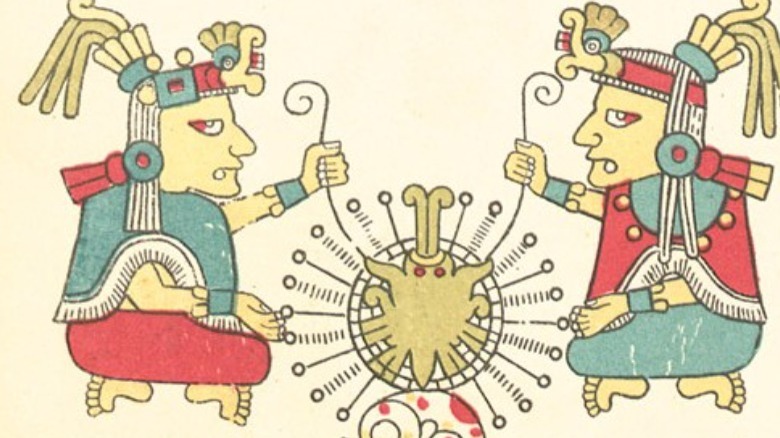

Ometeotl the God of Duality

The primal source from which all the universe was created is Ometeotl, the god of duality. As explained in "Aztec and Maya Myths," the Aztecs believed that the world was created out of interdependent but opposing forces. These two forces, male and female "creative principles," are manifested in two different deities, Tonacatecuhtli and Tonacacihuatl, from which humanity was born. Ometeotl's plane is the highest of heavens, the thirteenth heaven Omeyocan, also known as the level of duality.

Tonacatecuhtli and Tonacacihuatl were often called Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl, as explained in "The Mythology of the Aztec & Maya." It was from this pair, the dual form of omnipotent Ometeotl, that the four main gods, tezcatlipocas, were born. The white Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, resides in the west while the red Tezcatlipoca, Xipe Totec, lives in the east. The north belongs to the black Tezcatlipoca, and the south is under the command of the blue Tezcatlipoca, Huitzilopochtli. The cosmos was in disarray until these four gods finally separated heaven and earth and divided their shares of the sky.

The concept of one in many and vice versa was important for the ancient Aztecs, since many of their gods were able to take on different forms without losing their identity. Ometeotl created itself out of nothing, divided itself into two opposite deities, which multiplied further. One story describes how Omecihuatl suddenly felt she was pregnant, and gave birth to a sacred obsidian knife, out of which 1,600 gods and goddesses emerged.

Quetzalcóatl the God of Air

The white Tezcatlipoca is known for bringing abundance, balance, and harmony. He is also responsible for one of the most prized necessities in the Aztec world — corn. His image appeared in many places around the ancient Aztec world as a quickly recognisable feathered serpent, explains the book "Mesoamerican Mythology."

As per "Aztec and Maya Myths," Quetzalcóatl is connected to fertility, water, and everything that is associated with life. He represents the positive traits of the world, while his brother, Tezcatlipoca, is in charge of conflict and discord. They both appear in many stories about the creation of the world.

Quetzalcóatl is present in the myth about the origin of maize. After the gods decided to create humans in the time of the fifth sun (the time of the ancient Aztecs), they went to search for food to feed humans. Quetzalcóatl discovered an ant carrying a grain of maize and followed it to Tonacatepetl mountain. He turned into ant himself and climbed into the mountain, where he stole some maize and left. But the gods needed more corn to feed the humans, so they questioned how could they get their hands on the whole stock of corn. Quetzalcóatl tried to bring back the whole mountain, but the mountain was too big. With the help of the divine couple Oxomoco and Cipactonal and the other three tezcatlipocas, they blew up the mountain and scattered the maize in all four directions — with the maize going in each cardinal direction being a different color.

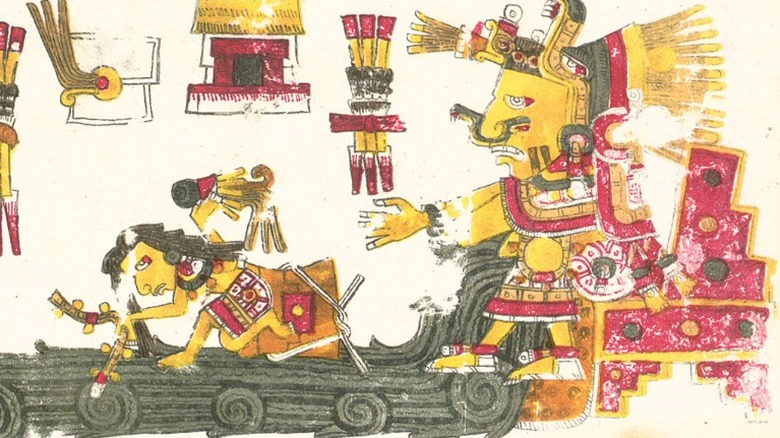

Tezcatlipoca the God of Smoking Mirror

The god of the night and the contrasting side of Quetzalcóatl, the black Tezcatlipoca, was often depicted as a jaguar, according to Britannica. He makes trouble everywhere he goes and is frequently seen in bad company. According to one of the myths, he convinced Quetzalcóatl to indulge in sex, sin, and alcohol — which led to the end of the Toltec golden age. He popularised human sacrifices in Central Mexico but was also the patron of young soldiers and even slaves. During his festival, a young warrior had to be sacrificed — but only after he lived like a king in a paradise for a year prior. He was portrayed with a black obsidian mirror, in which he can read people's minds and see their secret deeds. Black magic is his favorite thing.

But he has positive sides as well, overlooking destruction as well as creation. In one of the creation myths, he and Quetzalcóatl work together to restore the world after the demolition of the fourth sun (the era before the ancient Aztecs). As explained in "Aztec and Maya Myths," the four tezcatlipocas created four roads heading towards the center of the earth. From these four quadrants they raised up the sky, and Quetzalcóatl and Tezcatlipoca turned themselves into majestic trees to support the heavens. Quetzalcóatl's was adorned with greenish feathers from quetzal birds, and Tezcatlipoca's had black mirrors. This is how they became the lords of the skies, with a Milky Way as their own personal path.

Xochiquetzal the Goddess of Women and Weaving

According to Britannica, Xochiquetzal is an Aztec goddess of sex, beauty, and domestic craftsmanship, such are weaving and embroidery. She is also a patroness of plants, flowers, and other greenery.

As explained in "The Mythology of the Aztec & Maya," she is also connected to childbirth, pregnancy, and even sex work. She is married to Tláloc but was kidnapped by Tezcatlipoca, who glorified her to become the goddess of love. Tezcatlipoca, the lord of the night, fell in love with her exquisite beauty. She defied his seduction, so he took her to the underworld where he raped her.

Another legend about Xochiquetzal recounts her banishment from heaven. She resided in Tamoanchán, the thirteenth of heavens, among rich flowers and exquisite nature. It was a place where humans were created at the beginning of the fifth sun but were later driven out of the celestial realms. The goddess of weaving spent her days creating delicate tapestries, when one day she decided to walk around the gardens. She decided to eat a fruit and pick some flowers from a special tree, declared sacred by the lord Ometeotl. The tree fractured in two, and blood started to bleed out of it (via "Mesoamerican Myth"). The supreme god sent Xochiquetzal into exile on earth, where she forever mourned the loss of her home. Her teary eyes couldn't see all the various flowers she created, and she became known as Ixnextli, or "Ash Eyes."

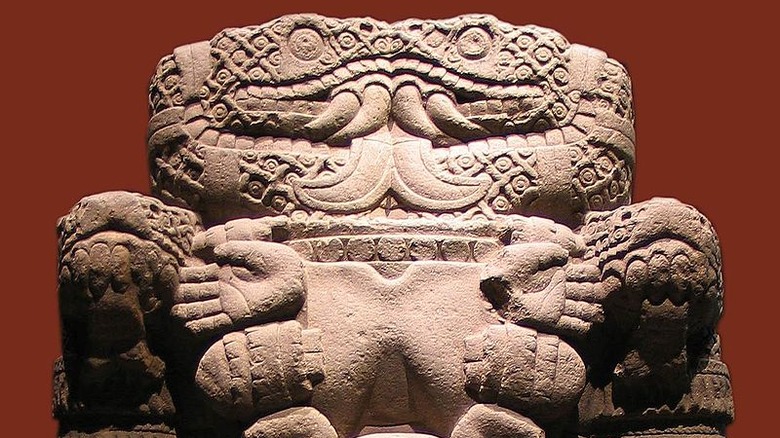

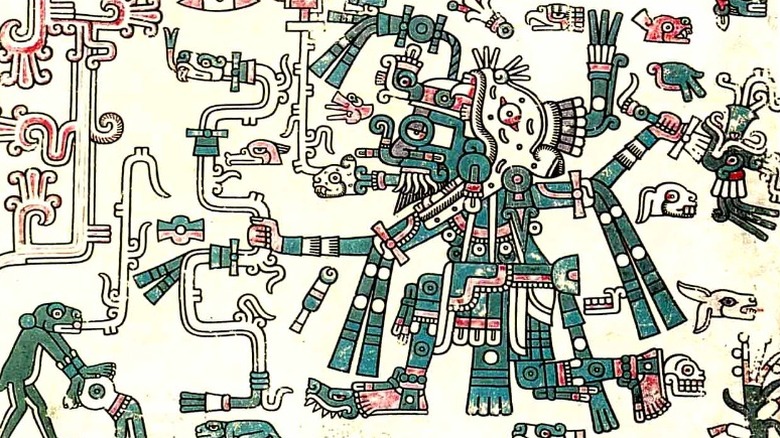

Coatlicue the Goddess of Fertility

Coatlicue is the ultimate earth goddess, "mother of the gods and mortals," according to Britannica. She has the power to give life as well as to destroy and rules over the realms of conception and death. She is surrounded by snakes, symbols of fertility, wearing them on her face and as a skirt. She eats corpses and wears their hearts, hands, and skulls around her neck. She is a patroness of childbirth and has many faces: snake woman Cihuacóatl, mother figure Tonantzin, or Tlazoltéotl, the goddess of sexual deviations.

The legend about Coatlicue, as summarized in "The Aztecs; People of the Sun," describes the life of the ancient goddess of the earth. She gave birth to the moon and the stars but lived in celibacy as a priestess afterwards. One day, she found a ball of feathers, which made her pregnant. This angered her children — the moon Coyolxauhqui, and the stars Centzonhuitznáhuac — so they wanted to kill her. But her unborn child promised to defend her against whatever came. When Huitzilopochtli was born, he kept his promise, killing Coyolxauhqui with a ray of sun and banishing Centzonhuitznáhuac.

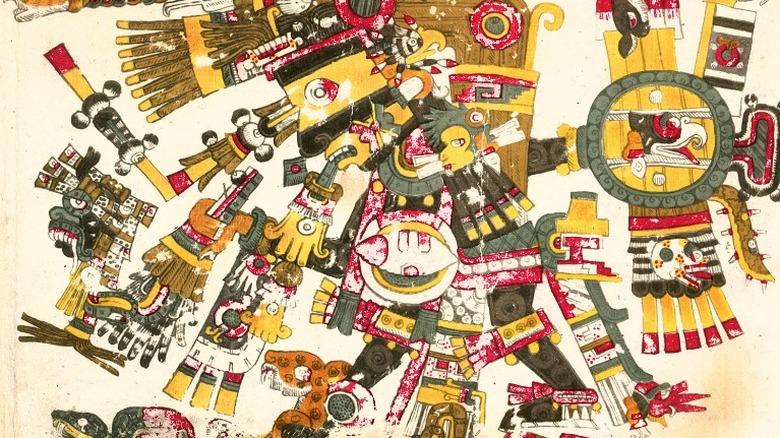

Huitzilopochtli the God of War

Huitzilopochtli is the supreme Aztec god, the great warrior. Born of goddess Coatlicue, he entered the world as a warrior, slaying his brothers and sisters on the go.

As outlined in "The Aztecs; People of the Sun," Huitzilopochtli's battle with the moon and the stars takes place every day anew. Every day, he wins the battle again, bringing daylight into the world. When dawn arises, the battle is complete, and to celebrate it, the god is carried through the sky by the souls of dead warriors. By midday, he reaches the center. There, the souls of women who died at childbirth pick him up and carry him towards the edge of the earth, where the sun sets.

The sun god needs a lot of energy to perform this battle over and over again, overpowering the infinite number of stars every night. For that reason, the Aztecs believed they must feed the sun with chalchíhuatl — human blood, life itself. Battle was seen as a form of ritual, an offering to the great Huitzilopochtli. Human sacrifice was another form of worship practiced in the ancient Aztec world. According to "Mesoamerican Mythology," sacrifices took place at the Templo Mayor, the central temple in Tenochtitlán. Using obsidian knives to open the chests of the victims, priests took their hearts out and dismembered them, offering their meat to the aristocracy who ate it ceremoniously.

Coyolxauhqui the Goddess of the Moon

Per the World History Encyclopedia, Coyolxauhqui was the sister of Huitzilopochtli, closely involved in his brutal birth story. She rebelled against their mother Coatlicue when she became pregnant with Huitzilopochtli. Trying to kill their mother, she led her 400 brothers, Centzon Huitznaua, stars of the south sky, against the great goddess. But one of the Huitznauas warned Huitzilopochtli while he was still in womb, so Huitzilopochtli jumped out of Coatlicue and started his murderous hike. He divided Coyolxauhqui's body and cut off her head, but to please his grieving mother, he put the head in the sky, turning her into the moon. As the goddess of the moon, she is overpowered every day, making way for the god of the sun when he arises. The Aztecs led their prisoners to her sacred stone circle so they would recognise they were defeated, much the same as Coyolxauhqu.

The goddess Coyolxauhqu was created after the Mexican fire goddess Chantico, and she is often portrayed wearing metal bells, her name translating as "painted with bells." However, it is still not decided whether she was really a moon goddess, some scientists speculating she could represent the Milky Way instead, as explained in "Aztec and Maya Myths."

Chalchiúhtlicue the Goddess of Water

Chalchiúhtlicue is the goddess of the sea, ocean, rivers, and lakes, but also fishermen and watercarriers, explains "The Mythology of the Aztec & Maya." She is often depicted wearing different types of blue and green, a jade skirt, a dress covered in seashells and jewelry made out of turquoise. She is married to Tláloc, although in some places, the sources mention her as his sister or even daughter. Sometimes, Chalchiúhtlicue is depicted as a frog, the animal usually connected to Tláloc.

As emphasized in "Ancient Mesoamerica," Chalchiúhtlicue's realms were the sacred rituals: birth rites, ceremonial purification, royal initiation, and funeral preparations. She had many different names, resembling many different states of water, which is always fluid and moving.

Chalchiúhtlicue presided over the fourth sun and was a great ruler, loved by her people. But cunning Tezcatlipoca blamed her for faking admiration for her people, so she would win their hearts, which hurt her deeply. She started to cry and cried tears of blood for the next 52 years, which flooded the world and ended the era of the fourth sun. Humans survived, but only because they transformed themselves into fish, per Mythology Source.

Mayahuel the Goddess of the Maguey Plant

The story of Mayáhuel is closely connected to pulque, a light alcoholic drink made out of the maguey (agave) plant. As described in "The Mythology of the Aztec & Maya," the fable begins with god Quetzalcóatl, who decided to create a drink for people so they would feel joyful and excited. He then met Mayáhuel in the highest of the heavens, and they quickly fell in love. Mayáhuel followed Quetzalcóatl down to Mesoamerica, where they transformed into a tree so they could become one. This angered Mayáhuel's grandmother, one of the tzitzimime — a night demon — who quickly sent a bunch of fellow demons after the amorous couple. They split the tree in two and tore Mayáhuel into pieces. Quetzalcóatl buried what was left of his lover far away from the crime scene, and while traveling to the location, he wept tears of despair. These tears fed the earth, from which maguey plants started to grow, the remains of the beautiful Mayáhuel.

According ThoughtCo, Mayáhuel is sometimes depicted as a woman with 400 breasts, breastfeeding 400 rabbits, who are smaller deities connected with drunkenness. She oversees alcoholic intoxication, but also fertility and revitalization, transformation from hardship to success.

Tláloc the God of Rain

According to Britannica, Tláloc is one of the oldest deities and, sharing the throne with Huitzilopochtli, the ruler of the Aztec pantheon. One of the two main temples in Tenochtitlán was built in his honor.

As explained in "The Mythology of the Aztec & Maya," Tláloc is in charge of rain but is also the most important among fertility gods. He oversees every possible precipitation, from light drizzle to wrecking frost, additionally throwing lightning if he is in the mood. He is often depicted with a face formed by snakes and has a hat resembling mountain peaks, though some of his other symbols are a frog and a duck, both animals connected with water. The ancient tribes practiced a custom in Tláloc's honor: When they celebrated the festival of Atlcahualo, priests impersonated frogs, jumping into the waters of Lake Texcoco.

Alongside commanding rainfall, he overlooks mountain rivers as well, storing the water in the mountains surrounding the Valley of Mexico. His spirit personnel, tláloques, help him gather the water in the mountains, while god Quetzalcoatl helps them to clear the path and bring water to the valley. He also has a dual nature, able to bring abundance or distress. The Aztecs believed he has four jars, one for each direction of the sky. If he opens the one which belongs to the east, the conditions are good, but if he opens any other, sickness might appear.

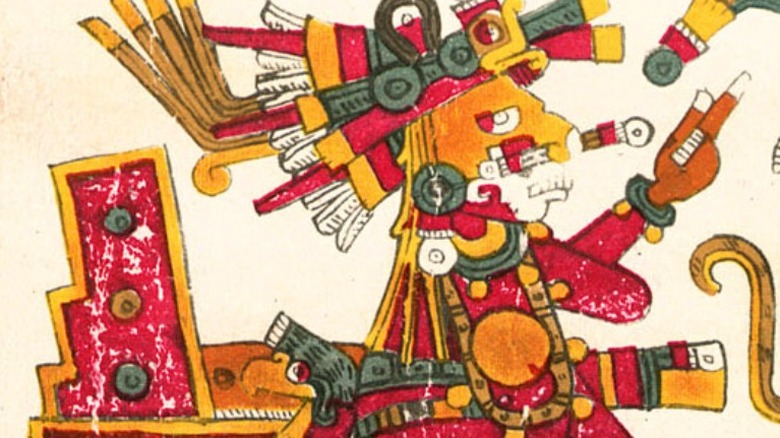

Xipe Totec the God of Spring

Xipe Totec is one of the four Tezcatlipocas, the red one, supervising the eastern part of the earthly kingdom. He is the god of agriculture, renewal and the first growth of corn, explains "The Mythology of the Aztec & Maya."

The Aztecs celebrated a special festival in his honor, the Tlacaxipehualiztli festival, also called flaying of the men. On this festival, human sacrifices were made by shooting arrows into victims, who bled out, with their blood symbolically representing the first spring rain. Another set of victims were fully skinned, providing the priests with their skin, so they could wear it for a month after. This practice was created to mimic the process of seed splitting, resembling the layered nature of the seeds, which grew from inside out.

According to ThoughCo, Xipe Totec is often portrayed wearing human skin, but he's also symbolized in the form of a death mask. These masks have hollow eyes and open mouths, covered by a hand. The god is also seen wearing a hat, ribbon headdress, or a skirt made out of sapote tree. Sometimes he holds a cup, a shield, or a rattle. Bats are his creatures, often carved into his statues.