Times Downton Abbey Got History Wrong

Combining the pleasures of trashy soap operas with prestige historical fiction, "Downton Abbey" was a phenomenon when it first hit TV screens in 2010 (in the U.K.) and 2011 (in the U.S.). No one at the time could have predicted that a fussy mini-series airing on PBS in this country would become a viral hit, but "Downton" soon became that rarest of things: A universal reference point. For a while, it was one of the few things you could reference in pop culture that everyone in your audience would understand.

It's easy to forget that the show was huge. According to The New York Times, when Season 6 premiered in January 2016, it drew nearly 10 million viewers. Vulture puts that into perspective by noting that this wasn't much less than the finale of "Breaking Bad" drew — and was about twice as many viewers as the finale of "Mad Men" generated.

Any time a show becomes that much of a viral hit, it gets scrutinized. But when the show is a historical drama like "Downton Abbey" there's an extra dimension to the scrutiny: historical accuracy. Over the course of six seasons and one film (so far) "Downton Abbey" has progressed from 1912 to 1927, chronicling a period of huge change in the United Kingdom and the world. Although the show has done an admirable job of maintaining period accuracy, there have been a few hiccups along the way. Here are the times "Downton Abbey" got history wrong.

The Crawleys are unrealistically progressive

Historical inaccuracy is kind of baked into "Downton Abbey." As a soap opera, almost all of the storylines involve the interactions between the aristocratic Crawley family and the servants who keep their ridiculously enormous country house running.

And those interactions are almost universally unrealistic for the time period. As noted by History Extra, while some of the wealthy nobles described their relationships with servants in "friendly" terms, this was almost always one-sided. Servants were expected to know their place and there was very, very rarely any sort of intimate relationship or true friendship. As The Guardian reports, the show takes pains to sanitize the reality of life in a house like Downton Abbey. The servants were often unhealthy and dirty, sleeping in freezing quarters and having no water with which to wash. And the way the Crawleys go out of their way to care for their servants is portrayed through an extremely modern lens — in reality, a family like the Crawleys would never do something like pay for Mrs. Patmore's eye surgery, or allow Tom the chauffeur to marry their daughter and then welcome him upstairs with open arms.

As noted by Better Homes and Gardens, the Crawley family is generally far too progressive for the time, somehow managing to be the sole aristocratic family in England completely unmarred by racism, homophobia, and antisemitism except in their most mild and quickly-curable forms.

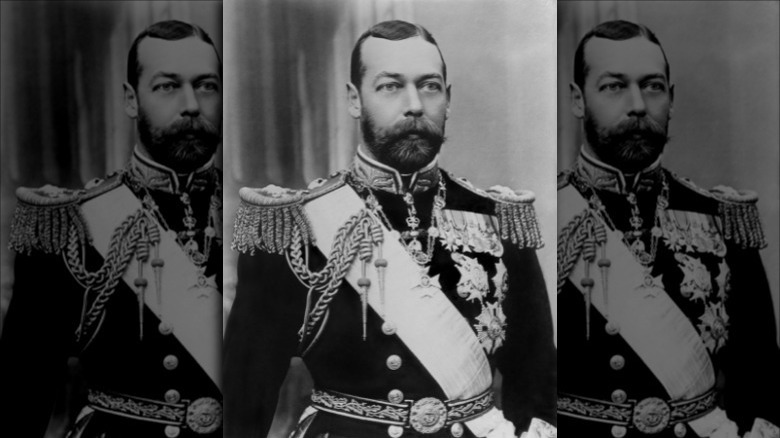

Irish radicals never tried to assassinate King George V

"Downton Abbey" proved its success in 2019 by releasing a film that extended the story past the end of the series (which had come a few years earlier). Set in 1927, as noted by Variety, the main storyline of the film involves King George V visiting Downton Abbey, which throws the household into an uproar. And History vs. Hollywood notes that the visit also prompts Irish nationalists to use Tom Branson in order to get close to the king for an assassination attempt. While this makes for some tension and action in the film, it's completely inaccurate: No such assassination attempt was ever made, and in fact, relations between Ireland and Great Britain were in a relatively quiet period at that time. As Time notes, the real violence between the two countries ended in 1921, and the Irish Free State had almost immediately plunged into a civil war that ruined its economy. This left the Irish with more pressing concerns.

According to Bustle, there were some undeveloped schemes to assassinate the king, but these never progressed very far. This is due in part to the fact that King George V simply wasn't very involved in Irish affairs, so there was very little reason for even radical Irish folks to want him dead. It's much more likely the storyline was invented to give Tom Branson something dramatic and heroic to do.

The Crawleys are too friendly with their servants

"Downton Abbey" is set in the waning years of the classic English country house. These were enormous homes on large, intricately-manicured lands. As noted by CNN, most of these "stately homes" were built in the 17th and 18th centuries — and they were incredibly expensive. One of the main expenses was the servants, and there were a lot of them — some of these houses had hundreds of people keeping them going.

And "Downton Abbey" makes it look like it wasn't a bad life — especially because the Crawleys are so friendly. They always treat their employees kindly and like human beings, and they even express great affection and intimate trust in them. But according to historian Jennifer Newby in Wales Online, this is incredibly inaccurate. Servants and their employers almost never interacted beyond what was necessary to get the work done — an employer would never ask their servant for advice or have a personal conversation with them. According to Time, other interactions like Lady Grantham gossiping with her maid or discussing the dinner menu with her cook simply would never happen.

According to author Lucy Lethbridge in her book "Servants," the staff of a house like Downton would have been regarded as "part of the general furnishings," meaning the aristocrats they worked for paid almost no attention to them at all. In other words, it wasn't necessarily cruelty or unkindness — in real life, the Crawleys wouldn't have thought about their servants at all.

Half the dialogue is anachronistic

Although not tied to a specific historical event, the language used in a period piece like "Downton Abbey" is as important as any other historical detail. And when it comes to that language, the show is actually pretty terrible. As noted by Babbel Magazine, most of the language used by the characters on the show is inaccurate. This is largely due to a practical concern, of course: The show is aimed at modern audiences who might find a more accurate use of language tedious — or even a bit silly.

According to NPR, some examples of the blatantly inaccurate language used on "Downton Abbey" include seemingly common phrases like "I'm just sayin'," which didn't enter common usage until after World War II, "step on it," which was in use at the time but almost exclusively in America, and "when push comes to shove," which was almost exclusively used by Black Americans until after World War II.

One word most people wouldn't imagine lands on the list of anachronistic words and phrases is "pregnant." Although considered a common and uncontroversial way to describe someone's physical state today, in the early 20th century, it was considered crass. In fact, the word was usually reserved for describing farm animals, and even a lowly maid working at Downton would have been insulted to be referred to that way.

Thomas Barrow's homosexuality isn't treated realistically

Thomas Barrow, footman and eventual butler at Downton Abbey, is often the villain in the show's early seasons. Which is problematic in some ways, as he is also the sole gay recurring character in the franchise. But even putting aside the choice to make your one gay character a scheming grifter, Barrow's homosexuality isn't very historically accurate.

For one thing, although homosexuality was officially illegal in the time period of the show and film (according to Harsh Light News, laws outlawing homosexual acts dated back to 1533 in England), that didn't mean there was zero gay culture. Bustle notes that there was a "vibrant and rich" underground gay culture in England at the time. According to The Toast, there were bars like the Café Royal in London that were essentially gay bars, and Vice notes that Madame Strindgberg's Cave of the Golden Calf, opened in 1912, is often regarded as the first modern gay bar. In other words, in reality, Barrow would have had opportunities to know and associate with a whole gay culture, if only intermittently.

At the same time, everyone is far too supportive of Barrow when his sexuality becomes an open secret. While it's possible that some of Barrow's peers and employers might have been sympathetic (or disinterested), having the entire community rally around him is unrealistic for the time.

Maids had more to fear from upstairs than downstairs

One of the most shocking moments in the "Downton Abbey" series was when maid Anna Smith was sexually assaulted by a visiting valet. The scene was upsetting to many viewers, and it even sparked an investigation in England after viewers wrote in complaints about its graphic nature, according to The Guardian.

Historically speaking, the problem isn't with the idea of a servant being assaulted in one of England's grand country houses — that certainly happened. As noted by The Toast, the problem is that when it happened, it usually involved men from upstairs, not downstairs. In other words, it was usually the maid's employer or one of the other aristocrats associated with the house, not a fellow servant. According to HuffPost Entertainment, maids assaulted by their employers were so common that the concept of the "ruined maid" was universal. As explained by historian Alison Maloney in her book "Life Below Stairs," maids were often threatened with sexual assault if they didn't voluntarily sleep with their employers, but were blamed and fired if they were found to be pregnant — no sketchy valets needed.

Even Anna's inability to prosecute the valet isn't particularly accurate, as most assault cases at the time were judged more on reputation than anything else. Anna's sterling rep and solid marriage would have made her a very sympathetic accuser.

The World War I leave situation

The first season of "Downton Abbey"' begins in 1912, and the story of the Crawley family and the servants who keep their country house running proceeds from there. So it was inevitable that World War I, which began in 1914, would eventually intrude on the show. And it's also kind of inevitable that the show would run into some sort of historical inaccuracy as a result — though the actual detail it gets wrong might be surprising: leave.

As noted by Slate, the heir to the Crawley estate, Matthew Crawley, dutifully heads off to fight as a Captain — but then seems to spend a truly shocking amount of time strolling about the grounds of his future estate instead of, you know, fighting the war. Although the timeline is a bit muddy, it certainly seems like Matthew can just jet home whenever he likes. According to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War, leave policies were messy, and there were huge class disparities, but on average a British Officer would get leave every three months.

But officers on leave weren't given any resources — they had a few days off, but as noted by Imperial War Museums they had to use a lot of that time traveling. One soldier recounted getting six days leave in 1915 — and spending three of them traveling to and from Scotland. Matthew could have conceivably traveled back to Downton Abbey on leave, but not nearly as frequently — or easily — as the show depicts.

Way too many servant marriages

One reason people fell in love with "Downton Abbey" is the sheer number of people who fall in love on the show. This includes both the upstairs aristocrats and the downstairs servants — and that's not exactly historically accurate.

As noted by History Extra, the servants in an English country house in the early 20th century would have been strongly discouraged from getting married. For one thing, as noted by The Los Angeles Times, servants were expected to live their lives through their employer's lives and not have any sort of individual identity. Even healthy, romantic relationships between servants were considered good cause for dismissal. There was rampant suspicion that romantic partners from outside the house would turn out to be thieves.

According to author Lucy Lethbridge in her book "Servants," female servants often viewed marrying an escape from the drudgery of their work — they looked for partners outside the house. For male servants, marriage was actually considered to hurt your career prospects. Married servants were thought to have "divided loyalties," and there was also the question of space. Married servants often meant children, and it would have been "unimaginable" for them all to live in the servants' quarters.

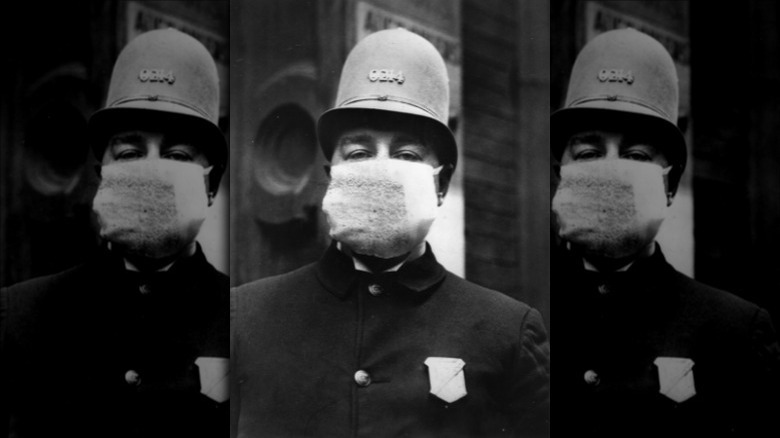

The Spanish Flu epidemic was a lot worse

"Downton Abbey" does get some of its history correct. As noted by EW.com, for example, the show has worked to keep depictions of characters touching each other to a minimum. This is true to the time period because of the lack of effective treatments for communicable diseases, and in later seasons of the show because of the impact of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 that killed an estimated 20-50 million people, according to History.

Which makes it surprising that the show's treatment of the Spanish Flu is terribly inaccurate. As Historic UK notes, the Spanish Flu killed more than 228,000 people in England alone, but you wouldn't know it from the show. As Vanity Fair notes, "Downton Abbey" treats the pandemic as "a rare, 20-minute illness whose specialty is romantic devastation." It's examined in a single episode in Season 2 of the show and never mentioned again, and there are precisely three cases mentioned in the episode, two of whom recover totally unscathed while the third arguably dies from a more sinister disease known as plot convenience.

As noted by The List, the show depicts exactly zero of the effects of a global pandemic. The New York Times reports that just like with the COVID-19 pandemic, mask mandates (and arguments about them) were everywhere in 1918 — but "Downton Abbey" doesn't show any, and the characters don't even exhibit any worry over a deadly disease rampaging around the world.

The show ignores the dark side of family wealth

"Downton Abbey" is not meant to be a historical document, of course, and it bends reality in order to make its characters likable. This is especially evident with the Crawleys, the wealthy owners of the country estate. It would be easy to hate these rich, often out-of-touch landlords, so the show goes out of its way to make their wealthy cluelessness funny and to emphasize their warm, good hearts, even if it's unrealistic.

One subtle way the show does this is through the source of the Crawleys' money. As noted by Forbes, Downton Abbey makes money mainly from rents paid by tenant farmers — good, wholesome money — and is sustained in large part by Cora Crawley's family money. Neither of those sources of wealth is particularly evil, but in reality, most of the families that owned those stately houses in the English countryside had deep connections to the slave trade. As noted by The New Yorker, a great many of those wealthy families made some or all of their generational wealth in the slave trade prior to its abolition. And as The Guardian reports, those families were compensated by the government for their lost slaves in what was the largest government bailout in British history until 2009. But not only are the Crawleys carefully inoculated against this truth, the show doesn't even attempt to reckon with it.

The entail was more complex than you think

"Downton Abbey" begins with the Crawley family in crisis: as explained by Forbes, Lord Crawley doesn't actually own the property (which would be known as a "fee simple" ownership). He's only given control of Downton under a series of conditions, one of which is who inherits it from him (known as a "fee tail"). This is why everyone on the show refers to Downton being "entailed." Lord Crawley can't leave it to his daughters because the entailment requires it go to his male heir, which turns out to be distant cousin Matthew.

This conflict drives much of the early storytelling — but the show isn't exactly accurate in how it handles the law. As far back as the 15th century, it was possible to "disentail" a property, though it required the consent of the heir. And the Fines and Recoveries Act of 1833 allowed entailed properties to be "disentailed" pretty simply. While it's believable that Lord Crawley would have had some work to do, the show's constant assurances that the entail on Downton was unbreakable doesn't hold up.

Even if the legal complications were too much to unravel, "Downton" ignores another fact that would reduce the drama quotient: Entails were abolished in England in 1925, which is when the sixth season of the show takes place. At this point, Lord Crawley's grandson George is the heir free and clear — but he could choose to declare his daughter the heir instead, if he wanted.

Lady Sybil should have lived

Period dramas often play up the fact that medical knowledge wasn't as advanced as it is today. But these shows can go too far in the other direction, which is what happened when "Downton Abbey" told the story of Lady Sybil's tragic death. As noted by The Washington Post, Sybil dies of eclampsia, a poorly understood condition affecting pregnant women and causing a deadly rise in blood pressure, cellular damage, and potentially seizures, stroke, and death. Eclampsia is preceded by a series of warning signs known collectively as preeclampsia — swelling in the legs and ankles, high blood pressure, headaches, nausea, and protein in the urine.

The family's country doctor, Doctor Clarkson, notes almost all of these symptoms and correctly urges Sybil to go to a hospital, but the more aristocratic physician in attendance does not concur, and so Sybil dies. But as noted by The British Journal of General Practice, eclampsia could be very well managed by the early 19th century, and treatment protocols had reduced fatality to less than 4% of cases. These treatments were "quickly adopted" worldwide, and it's not realistic a practicing doctor at the time would be unaware of them — or disagree with them.

There was also another common treatment both doctors should have been aware of: magnesium sulfate. According to The National Library of Medicine, this medication was in use in the early 1900s and has been shown to be very effective in managing eclampsia.