Most Important Battles Of World War I

World War I (1914-1918) was one of the largest and deadliest conflicts in human history. History says that the "war to end all wars" featured radical new technology that commanders on all sides, set in the ways of the 19th century, didn't quite understand. The resulting slaughter stunned the world and produced human misery on a scale not surpassed until World War II.

The western front, fought primarily between Britain (and affiliated nations like Australia, New Zealand, and Canada) and France against Germany, was defined by the bloody stagnation of trench warfare. Elsewhere — at sea, in the east, in the mountains of northern Italy, in the Balkans, the Ottoman Empire, and even outside of Europe — the front lines were more fluid, but the bloodshed was no less severe.

Here are some of the most important battles in the war that set the stage for the 20th century.

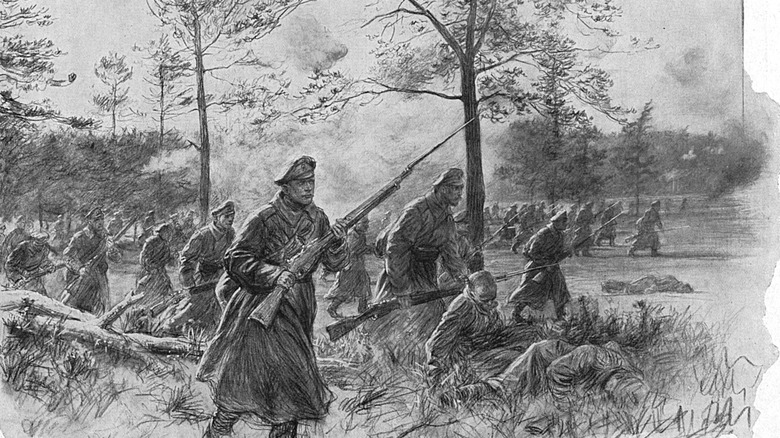

Battle of Tannenberg

At the beginning of the World War I, Germany had concentrated the bulk of its forces against France and Britain in the west, according to History. When the Russians mobilized with unexpected speed and marched into East Prussia, Kaiser Wilhelm II's forces scrambled to respond. Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff, the two senior-most German commanders, ordered their men to attack with maximum aggression to throw the enemy off balance.

The two Russian armies had no idea what was coming. Rather unwisely, History points out, they were each on opposite sides of the great Masurian Lakes. This made communication and coordination next to impossible, and allowed the Germans to defeat each force in detail.

The German assault began on August 26, 1914, and forced Russian Gen. Aleksandr Samsonov's second army into retreat after three days of heavy bombardment. Then the Germans cut off their escape, and slaughter began. It was the greatest victory Germany would enjoy on the eastern front. As for the Russians, the loss was so complete that Samsonov shot himself in the woods on August 30, rather than face the humiliation of his army's collapse.

At the Battle of Tannenberg about 50,000 Russian soldiers were killed, with 92,000 taken prisoner, History says. But it wasn't all in vain. History does note that at tremendous cost, these operations forced the Germans to weaken their western units by two corps. The German drive in Paris was soon thrown back.

First Battle of the Marne

World War I's western front began with the Schlieffen Plan: Germany's attempt to knock France out of the war in a single decisive strike before turning its attention to the east, as per Alpha History.

The attack went well at first, but Belgian and British resistance delayed the kaiser's troops long enough for their comrades to organize. The Germans did manage to get within striking distance of Paris itself, but the French rallied. They even sent 3,000 infantrymen to reinforce the front via taxis from the city, which Britannica notes is the first instance of automotive troop transport in the history of warfare. More significantly, Britannica says it was the seizure of an opportunity to strike at the exposed German flank that saved the capital.

The article notes that while Paris prepared for a long siege, the Allied armies forced a sizable gap between two German armies. This gap was widened when, on September 8, 1914, French Gen. Louis Franchet d'Esperey's Fifth Army made a surprise night attack.

The Germans were retreating within two days. The Allies caught up with them, and both sides began the "race to the sea," as it became known (via History Crunch), in an attempt to outflank the other. Neither side won, and this produced a stalemate. By this point the fighting was so severe that the only way to survive was to dig deep and stay below the ground. Trench warfare had begun.

Battle of Gallipoli

World War I was just a few months old in February 1915, but already, a frustrating stalemate in the trenches of the western front had planners on both sides trying to find other ways to attack the enemy. And while the Ottoman Empire, which entered the scene in November 1914, wasn't Britain's strongest opponent, that was the point. They believed that an operation to force the Dardanelles straits and capture Constantinople could help throw the enemy off balance and, as Britannica points out, help the Russians on the Caucasus front.

Winston Churchill was first lord of the Admiralty at the time, and a huge proponent of the plan to use Britain's older warships to absorb the Ottoman fire and break the line, and then have newer vessels steam in and deploy troops.

Unfortunately for the British, bad weather and cold feet bungled the operation almost immediately. Allied forces did manage to secure a number of beachheads, but Britannica notes these not only came at outrageous cost, but confusing orders about how to proceed thwarted any hope of achieving a decisive victory.

Britain, France, Australia, and New Zealand all sent divisions to fight in the battle (via the Smithsonian), only for the Ottoman defenders to dominate the field and deny them any breakthrough. The Entente abandoned the campaign in January 1916. Churchill himself resigned to command a battalion in France. But history wasn't done with him yet.

Battle of Verdun

The Germans, believing the war would be won or lost in France (via Britannica), tried on multiple occasions to win the western front with what The Atlantic describes as "a thunderstroke:" a single offensive that would smash the enemy and end fighting in the theater for good. Each attempt failed. In 1914, the assault was thrown back at the Marne. In 1918, they again neared Paris, only to exhaust themselves. The Allied 100 Days Offensive crushed them and ended the war.

But the most dramatic attempt was in between the two. The Atlantic describes how Germany had enjoyed great success in 1915 but was no closer to ultimate victory. It was imperative that the French Army be crushed once and for all.

The Atlantic details how the Germans depended heavily on a single advance towards Paris, smashing France's armies and the morale of its people. The city of Verdun was uniquely vulnerable, poorly defended, and too close to important German cities for comfort. It's capture would be a great boost to Germany and a morale-killer for the French.

But Gen. Erich von Falkenhayn's onslaught, begun in February 1916, did not produce the anticipated swift victory. On the contrary, Britannica notes, it led to one of the longest, bloodiest, most horrific battles of the war. The French won, at the cost of some 400,000 casualties. And neither side was any closer to victory when the smoke cleared that December.

Battle of Jutland

For most of World War I, the Germans were wary of engaging the much more powerful British Royal Navy.

But in May 1916, History says they gave it a shot: The bulk of the British fleet, comfortable after months of inaction, was away at Scapa Flow. German Adm. Reinhard Scheer decided to send his fleet — 24 battleships, five battle cruisers, 11 light cruisers, and 63 destroyers (via History) — to the Skagerrak, between Norway and Denmark, to target Allied shipping lanes and possibly pierce that troublesome British blockade.

But History notes that the British had cracked the German code and were able to respond quickly. At the end of the month, the royal fleet of 28 battleships, nine battle cruisers, 34 light cruisers, and 80 destroyers set out to engage its German counterpart.

On the afternoon of May 31, elements of the two fleets spotted each other, and sporadic fire was exchanged. By that evening, both fleets were fully engaged. By the next day, the British had outmaneuvered the German enemy, surrounding German ships with almost two to one, putting the enemy in an impossible spot. The Germans beat a skillful withdrawal and praised themselves for their crafty escape. But their fleet would never again see such action for the rest of the war.

In all, the Imperial War Museum says that 100,000 sailors on 250 warships fought in the war's largest — and only major — naval engagement. The British blockade remained strong.

Brusilov Offensive

After a rough start to the war, History Learning Site says that the Russian defeats at Tannenberg and the Masurian Lakes had made them excessively reluctant to go on the offensive against the Central Powers. However, the same article goes on to say that by 1916, the Russian equipment and training deficiency problems had largely been resolved. Now, they had to use their new army. And time was of the essence, as their western Entente Allies were struggling at Verdun and the Somme.

Gen. Alexey Brusilov led the offensive. The History Learning Site describes how heavily defended the target area was. But Brusilov hoped to offset this disadvantage by attacking in multiple sectors simultaneously, denying the enemy the ability to determine where the main effort was being made and reinforce accordingly.

The attack, which began on June 4 and which was aided by the element of surprise and excellent artillery preparation, met with instantaneous success. By June 8, the enemy was in full retreat. But one of Brusilov's armies, commanded by Gen. Aleksei Evert, did not attack, exposing the southern flank of Brusilov's forces and dooming the operation.

History Learning Site notes how close the Russian offensive came to success. Unfortunately, it failed to force the Germans to transfer large numbers of troops from the western front.

Battle of the Somme

July 1, 1916 was what Historic UK has called "the bloodiest day in the history of the British army." It wasn't supposed to be like this. In hindsight, it's hard to see how it could've gone any differently.

History UK claims that for months, French forces had been seriously battered at Verdun, east of Paris. The Allies wanted to divert German forces away from the battlefield by attacking further to the north, near the river Somme, and also cause massive casualties for their enemies. British and French divisions were placed north and south near the Somme in an effort to encircle German troops. In fact, the British were so sure of their success that the Germans would immediately flee, Historic UK reports they had a cavalry unit on standby to chase them all down.

But plans for a route were a bit premature. The preliminary, week-long, 1.7-million shell bombardment, which was supposed to wipe out the Germans before the Entente even got to their lines, failed to account for bomb-proof bunkers that housed the enemy. When the British recruits began their slow march across No Man's Land, they were cut to ribbons by unscathed German machine-gunners.

Despite the slaughter, the BBC notes it was still a strategic win for the Allies. The attack convinced the Germans that the Allies were growing in strength. In response, they escalated their submarine war against Allied shipping, which eventually forced America to declare war.

Battle of Passchendaele

In 1917, Britannica notes that British Gen. Douglas Haig decided to take the Ypres salient, a thorn in the Allied frontline in Belgium that had seen combat since 1914, after a bunch of French troops had mutinied.

The initial British attack at Messiness Ridge (which Britannica notes was made possible by the detonation of huge mines beneath enemy positions) was so successful ... that it helped the Germans in the long run. Now overly confident, the British made the same assumptions that embarrassed them at the Somme the previous year: The enemy will break immediately, and our cavalry will run them down.

You're likely seeing a pattern here. When the Third Battle of Ypres, known more commonly as Passcendale, began, assaulting British units were dismayed to find that the 4.5 million shells hadn't done much damage to the enemy, and they had turned the landscape into a horrific, swampy quagmire of loose earth and mud so thick that one soldier wrote, "If the ground had not been a bog and as soft as it was it is absolutely certain that I would have been blown to bits" (via the National Army Museum).

The museum notes that the British eventually "won" the battle, but only at outrageous cost, and they were forced to retreat the following year during the German Spring Offensive. The muddy horrors of the Battle of Passchendaele have since come to exemplify the mad, senseless tragedy of a Great War that was anything but.

Battle of Caporetto

Italy's involvement in World War I often goes overlooked, but there were enormous battles in the northern mountains of the country. As was the case on other fronts, harsh terrain and a nature of warfare that heavily favored the defender produced a lot of bloodshed for a stagnant frontline. After all, according to History, the Battle of Caporetto is also known as the 12th Battle of Isonzo.

But when the Austrian-Hungarians attacked in the region in October 1917, they encountered nothing like the resistance they'd offered the enemy. By the end of the first day alone, History says the Central Powers, attacking with flamethrowers and grenades to clear whatever Italians hadn't been blown out by the preliminary artillery barrage, had advanced an astonishing nearly 16 miles, dwarfing the mere 7 miles the Italians had gained in the 11 attacks they'd made in the same sector since May 1915.

By mid-November, the Italians had suffered some 700,000 casualties — about half due to desertion — and the front lines were only 18 miles from Venice. Italian commander Luigi Cadorna, who had overseen the Italian war effort thus far, resigned in disgrace as antiwar protests raged throughout the country. His successor would keep Italy on the defensive for the rest of the war.

Spring Offensive

Germany, who would go on to lose the Great War, actually began its final months from a position of strength. An ingenious plan to knock Russia out of the fight by dispatching and supporting communist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin had worked brilliantly, according to the New York Times. Germany now had massive forces freed up to hurl against the Entente powers in the west. But time was of the essence: the United States had joined the fight, and American doughboys were en route to European battlefields. It was imperative that Germany press its advantage while it still could.

According to History, German Gen. Erich Ludendorff masterminded Germany's "Spring Offensive," launched in March 1918. The assault began with a 9,000-gun artillery barrage, which quickly routed the British Fifth Army. For the next week, the road to Paris looked open. The Germans even got close enough to shell the city from 80 miles out with their mighty "Big Bertha" howitzers. By March 25, the Allied line at the Somme was broken, and German troops were pouring through.

But their good luck wouldn't last long. History goes on to detail how exhaustion, starvation, and stiffening Entente resistance ultimately blunted the attack, despite the Germans inflicting some 200,000 casualties and capturing 70,000 POWs. According to History, Ludendorff launched four similar attacks that spring in Germany's desperate last attempt to crack open the Western Front.

But it wasn't enough: the Allies were about to strike back hard.

The 100 Days Offensive

The German 1918 "Spring Offensive" had brought the kaiser's legions to within shelling distance of Paris, and had nearly broken the back of the Allied powers. But German troops were soon exhausted, starving, and caught out in the open. Frustratingly, the Entente powers, though badly mauled, were in much better shape.

The National World War I Museum notes that by summer 1918, Germany's once-brutal attacks had run out of steam. All along the front, the Allies had amassed advantages in manpower, ammunition, and other crucial supplies. On August 8, what German Gen. Erich Ludendorff described as "the black day of the German Army," British troops smashed the Germans near Amiens. In the center, the French later pressed the Germans back against the Hindenburg line. Southward, American forces began their attack in mid-September, forcing the Germans to retreat.

The Allies put into use all the lessons they'd learned after four years of trench warfare. For the first time, the museum notes, Allied infantry, tanks, planes, and artillery all coordinated their attacks, effectively operating like proto-WWII armies. The Germans, exhausted and outnumbered, disintegrated, leaving the empire defenseless. Soon, the kaiser had no choice but to sign an armistice. The Great War was over.