The Hubble Telescope's Greatest Discoveries

Given how quickly most technology goes obsolete and gets massive updates, it's pretty incredible to think that the Hubble Telescope has been doing its thing since it launched way back in 1990. Just imagine having the same phone that was brand new, out-of-the-box in the same year that "The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air" debuted, and that gives some idea of just how old it is.

Hubble has had some major issues, says Space, and it's had some huge upgrades. It's been serviced a few times, and if it was a human, it would be at the age to start to notice that its bones are getting creaky, there are weird aches and pains everywhere, and isn't the music in this bar just too loud? How is anyone supposed to have a conversation? Turn it down, please, and then get off the lawn.

Still, the Hubble Telescope has sent terabytes upon terabytes of data back to NASA, and interpreting all the things that it's seen way out there in space has yielded some incredible discoveries. Scientists have learned some shocking things about our galaxy — and the ultimate fate of the universe — all because this decades-old piece of technology is still out there: drifting, watching, and recording some wild things.

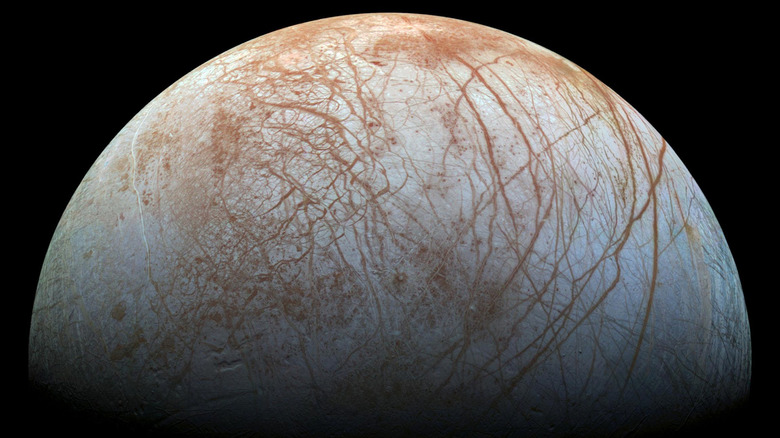

Water vapor on Europa

One of the longest-running mysteries of the universe is whether or not there's life on other planets, and regardless of which side of the argument a person falls on, there are still some discoveries that are wild enough to make someone say, "Hold up... repeat that?" That happened in 2013, when the Hubble Telescope got some head-scratching photos of Europa, one of Jupiter's many moons.

According to NASA, Europa has a bitterly cold surface temperature that's somewhere around -260 Fahrenheit. That means it's way too cold to support life as we know it, but Hubble photos show there might be something underneath Europa's frozen surface: water. The surface of the planet, it turns out, is pockmarked by geysers that are blowing water vapor through the ice and into space. (Europa has such a minimal atmosphere, nothing's getting held in for very long.)

Then, in 2015, they realized something else after analyzing data Hubble gathered between 1999 and 2015. On one hemisphere of the moon, there weren't just geysers spewing water vapor, but there was also water vapor being added to the equation from surface ice melting in the sun. Why was this just on one hemisphere? No one knows, but the discovery of water — and oxygen — on a body other than our own is a pretty huge deal.

The age of the universe

Star-gazing can be a humbling experience that puts things into perspective: The universe has been around way longer than any individual has, after all, and it'll continue long after. Just how long it's been around has been up for debate, but thanks to Hubble, NASA has an answer.

Technically, they have two answers. In 1999, teams from the Carnegie Institution of Washington and Harvard University released information on the studies they had been doing on Hubble data. The idea was — in a nutshell — to use a specific type of star to calibrate distance-measuring devices, equations, and other scientific gizmos. Basically. Measurements taken, retaken, and confirmed by Hubble were combined with findings on the density of the universe around us, and it gave NASA's Hubble Space Telescope Key Project Team a magic number of 12 billion years as the age of the universe... give or take. But that wasn't quite the end of the story.

In 2002, NASA made another announcement: Hubble had just discovered something truly wild, which are the "oldest burned-out stars in our Milky Way Galaxy." Thanks to other calculations that Hubble data had made possible, NASA already knew that it took a little less than a billion years for the first stars to form after the big bang. Taking that into account — and figuring out that these ancient white dwarf stars were around 12 to 13 billion years old — it was one more step toward figuring out a more precise birthday for the universe.

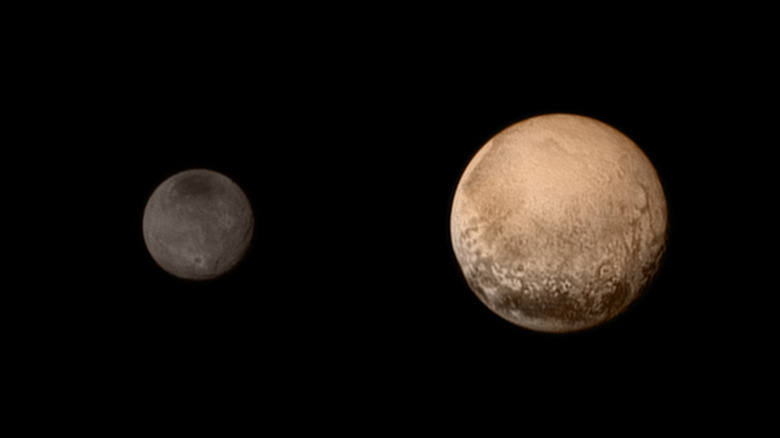

Pluto's moons

Pluto might be the outcast of our solar system, but it's still a pretty neat ... not-planet? And thanks to the Hubble, NASA learned that no matter what it's called, it has a few moons that do something weird.

Earth has a little bit of a wobble to the way it moves through space, and Pluto's moons Nix and Hydra put Earth's catwalk strut to shame. They don't just wobble, they do what NASA associate administrator John Grunsfeld describes as "a cosmic dance with a chaotic rhythm." They further explain it like this: If someone happened to be living on either one of them, there would be no way to predict where on the horizon the sun would appear to rise or set on any given day.

Nix and Hydra move like they do because they're caught in the middle of the gravitational pull between Pluto and Charon (pictured) — two "planets" that make up a double system where they rotate around each other. Nix and Hydra, meanwhile, are thrown in to spin around like the teacup ride at an amusement park. As if that isn't nail-biting enough, Hubble had made a prior discovery, too: In 2011, it was announced (via The European Space Agency) that Hubble had spotted a tiny moon — one that is only about 12 miles in diameter, give or take — that orbited Pluto from a position between Nix and Hydra.

Supermassive black holes

Black holes are, says Space, super-dense objects that don't let anything get away from them — not even light. That's pretty terrifying, and what's more terrifying? The presence of supermassive black holes, which are exactly what they sound like.

The first black hole was only discovered in 1971, and it has a mass of around 15 times that of our very own Sun. Then, when Hubble was launched, it promptly told NASA to hold its beer, and started providing what looked like evidence for black holes that weren't just a few times the size of the Sun, but even billions of times larger. The idea was — basically — that galaxies that collided with each other would provide the energy needed to generate a black hole larger than what anyone had seen before. And then, Hubble found evidence that not only do they exist, but they're actually pretty common — and they're at the beating heart of most galaxies, including our own. By measuring the speed of gases, astronomers can tell approximately where and how big these black holes are: The light and color signatures of gases moving at the most extreme velocities are a red flag signaling one of these black holes.

What, exactly, does it all mean? Astronomers haven't figured that one out yet, but with the discovery of supermassive black holes in the middle of galaxies, it's led them to think that they're an inevitable part of the life cycle of a galaxy.

The farthest galaxy in the universe

It's easy to say that the corner store or the nearest IKEA is a long way away, but let's put that in perspective with the help of Hubble and a research team from the University of Tokyo.

In 2020, astronomy professor Nobunari Kashikawa announced (via Space) that they had found the galaxy that was both the farthest away from us and the oldest. The rather disappointingly-named GN-z11 was calculated to be 134,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 kilometers away, and that really, really puts things in perspective.

That's not the first time GN-z11 got some serious attention, and it was back in 2016 that NASA announced Hubble observations had confirmed the galaxy wasn't just really far away, but it was way back in the past, too. The photos Hubble took of the galaxy are a snapshot of what it looked like between 200 million and 300 million years after the big bang, which is just about when stars were first starting to form. Hubble isn't just looking at things billions of light years away, it's looking at something as it was about 13.2 billion years ago. If that's not mind-bending, then nothing is.

A way to determine habitability of other planets

First, the basics: Ozone, says LiveScience, is essentially a layer of gas consisting of oxygen molecules bonded together, and it's important because it blocks the sun's UV rays. It's what makes life on Earth possible, as without it, everyone and everything would be fried like the opening to "Terminator 2."

In 2020, NASA announced they had used Hubble for something neat. During a total lunar eclipse — when the Earth passed completely between the Sun and the moon — they turned the moon into a mirror, and focused Hubble's attention on that. Sunlight which had already passed through the Earth's atmosphere was reflected off the moon and to Hubble, which captured the ultraviolet signatures and — more importantly — the presence of ozone. From that description, it's entirely possible to look at it and say, "Okay ... and?"

The announcement isn't awesome because it found ozone in Earth's atmosphere, it's awesome because it proved that the experiment can be used on other planets to detect ozone. The presence of ozone is one of the things astronomers look for when they're looking for planets that can support life, and the Hubble just showed how scientists can find what NASA's Giada Armey calls one of the "necessary ingredients ... common on habitable planets."

A mass of black holes

Dave Lister played "pool with planets" in an attempt to save Red Dwarf from a so-called "white hole," and while it makes for a hilarious gag on the show, it's an idea that's not entirely out in left field. In 2021, NASA announced that Hubble had discovered a "concentration of small black holes," and anyone who had that on their 2021 BINGO card can go ahead and cross off "Creepy Intergalactic Phenomenon."

The group of black holes was found in the heart of a globular cluster called NGC 6397, and it formed way back around the time of the big bang (relatively speaking). Over billions of years, the pushing and shoving match that is the gravitational pull between massive bodies has caused the black holes — the remains of collapsed stars — to sink toward the center of the cluster in what NASA describes as a "game of stellar pinball."

As with a lot of intergalactic, interstellar discoveries, there are a few parts: the discovery itself, and what it means. It's too early to tell at the moment, but researchers are suggesting that such a cluster of black holes might cause "ripples in spacetime," so keep that on the BINGO card.

How many galaxies are there?

While it's impossible to say that Hubble has discovered how many galaxies there are in the universe, it's safe to say that Hubble has proved the answer isn't just, "Lots," it's "Way more than anyone could have imagined."

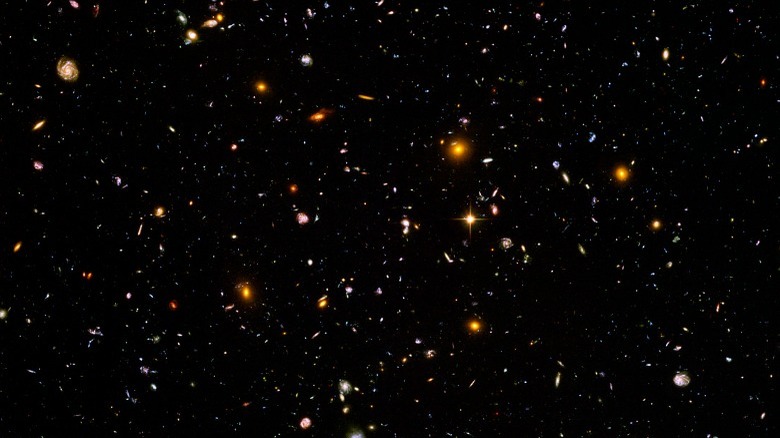

In 2012, NASA released Hubble's eXtreme Deep Field Photo (pictured, in part). It was essentially a single photo of one particular spot in the sky, made from combining 10 years' worth of data and images. It allowed for what Space called "the deepest image of the universe ever taken," and it was essentially made possible by Hubble taking photos of tiny bits of lights and then combining them, to create slightly brighter bits of light that we could see.

That single image contains thousands and thousands of galaxies, and here's the kicker. The photo looks like any old photo, but size does actually matter. That photo is actually inflated: Anyone who looks up at the night sky can get an idea of just how much the photo represents by holding a hand out — and upwards — into the sky. Now, imagine the head of a pin against your hand. The area covered by the head of that pin is what Hubble took decades' worth of pictures of, and that's where thousands of galaxies exist, well beyond what the human eye can see.

The mass of the Milky Way

One of the best things about the human race is that we all want to know things. Even things that don't really seem to serve any practical purpose — aside from on trivia nights — we want to know about them anyway. Like... how much does our galaxy weigh, anyway?

In 2019, NASA reported that they had, in fact, figured it out. They did it by combining data from Hubble (which has a small field of view but can see far, far away) and Gaia, the European Space Agency satellite (which has a more panoramic view of the sky). Mathematics and details aside, the final number was that the Milky Way has a mass of 1.5 trillion solar masses, which makes more sense when you know that one solar mass is the mass of our Sun.

And here's the really wild part. According to The Guardian, that means the Milky Way is one of the bigger galaxies in the neighborhood... but, there's a "but." There's around 200 billion stars in the Milky Way, but they only account for about 4% of the galaxy's mass. The rest is dark matter, that substance that we don't know too much about, aside from the fact that it holds the universe together, keeps the galaxies structured, and is all around us. And it's apparently heavier than you might think.

The dark matter map

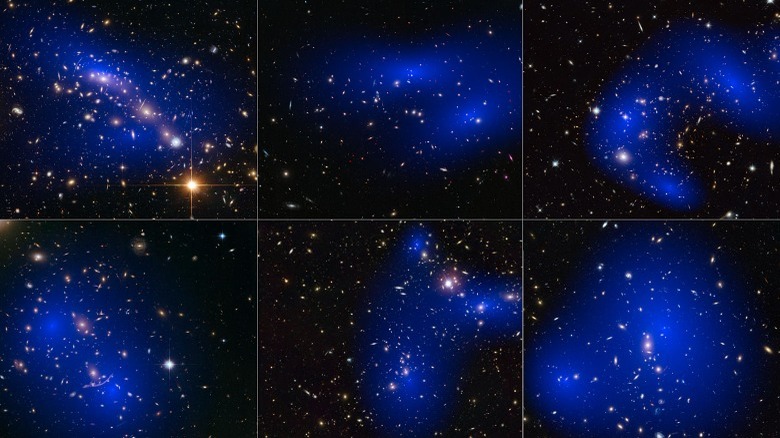

What is dark matter? Who the heck knows! According to Space, it's matter that's out there, but that no one can see. Yale University's Pieter van Dokkum explains how astronomers know it's there: "Motions of the stars tell you how much matter there is. They don't care what form the matter is, they just tell you that it's there." So, while no one can see it and no one's sure exactly what it is, NASA says Hubble has made a map of it.

It's more appropriately called a map of a galaxy cluster called Abell 1689, but the dozens of images were layered together to reveal much more than just the galaxy itself. Hubble can't see dark matter either, but it can see when it's looking through dark matter. When galaxies beyond massive concentrations of the stuff get distorted by the presence of this mysterious substance between the telescope and the distant galaxies, the amount of distortion can be interpreted and measured.

That's allowed for mapping something that scientists can't see and absolutely don't understand. And, since looking at distant galaxies is the same as looking at past galaxies, it's allowed researchers to start figuring out what role dark matter played in the birth of everything ... even if they're not yet sure just what it is.

The most distant star ever seen

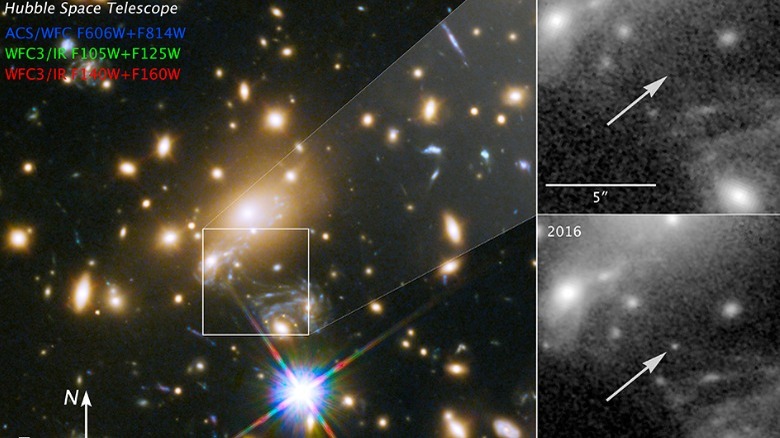

It looks like just another bright dot on another one of Hubble's many, many photos, but according to astronomers from the University of Minnesota, the telescope captured something really cool when it photographed that bright dot: it's the most distant star ever seen.

They weren't even looking for it at the time, and according to Silicon Republic, they were actually studying a nearby supernova called SN Refsdal when they noticed a pinprick of light that changed brightness across the photographs. Officially called MACS J1149.5+223 Lensed Star 1 but unofficially called Icarus, the little point of light ended up being 9 billion light years away.

That makes it about 100 times farther away than the next farthest star — that hasn't gone supernova — that scientists have to study. And that's kind of weird, especially considering that Icarus is, in fact, long-dead. A lot can happen in 9 billion years, after all, and the length of time it took the light of the star to get to Hubble's cameras means that in reality, the star died a long, long time ago. Still, we see it in all the glorious brightness of (relative) youth.

An inevitable collision

In 2015, NASA released what they called the "sharpest image ever taken of our galactical next-door neighbor," and it was a brilliant, beautiful photo from Hubble that showed the 61,000-light-year-long sweep of the Andromeda galaxy (pictured, in part). It was the first photo like it, and it took the compilation of 7,398 images to create. NASA has also said that we'd better get familiar with them, because in about 4 billion years, they're all going to be really, really close neighbors... the kind that hop the fence and grab a plate before even asking what's on the BBQ.

Hubble had been monitoring the movement of both the entirety of the Andromeda galaxy and a smaller, companion galaxy called Triangulum. Plugging Hubble's observations into computer simulations designed to see what the future holds gave a glimpse into one with a collision between the three galaxies.

Again, that's not going to happen for another 4 billion years, so there's no need to panic. Researchers also say that even when it does happen, it's unlikely there's going to be too many collisions — there's a lot of space in, well, space — and the worst our sun and solar system is probably going to see is that the whole thing gets kind of tossed around like a bit of laundry. Sure, there will be quite a bit of chaos as gravity sorts itself out, but anyone who's still around to see it happen can deal with the fallout then.

Planetary construction zones

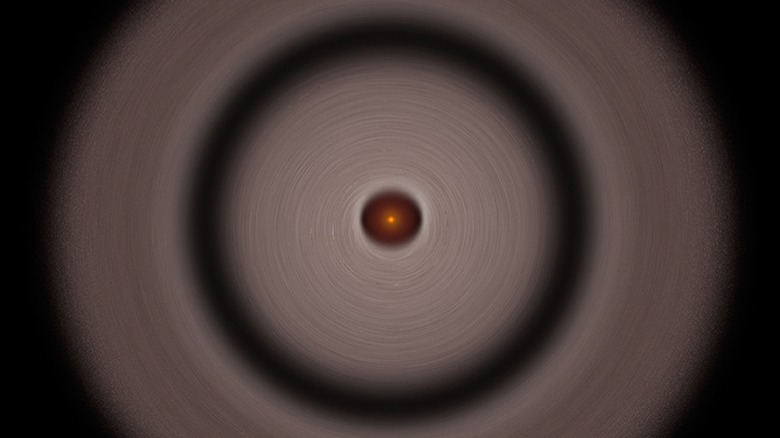

There have always been some questions about just how planets happen, and among Hubble's many discoveries is proof that planets are born in rings of dust and debris that orbit stars. NASA calls these areas "planetary construction zones," and two of the best examples that Hubble has photographed are the debris fields around the stars Beta Pictoris and TW Hydrae (pictured).

Although the light from the stars makes it hard to see, Hubble was able to detect and photograph huge empty spaces in stars' debris fields. Those empty spaces are essentially where a planet is forming, as the gravitational pull of the forming core attracts more and more dust and debris as it orbits.

According to the Center for Astrophysics from Harvard & Smithsonian, it also explains why the materials that make up planets and their stars are similar, but not precisely the same. There's an easy way to imagine this whole thing on a small scale, too: Just picture vacuuming up sand from carpet. Sure, the first pass is going to get a lot, but circle back and go around a few more times, and pretty soon, you'll have enough for a planet.

The first documented collision in the solar system

Collisions between planets, asteroids, and — usually — Earth are the basis for countless sci-fi movies, but here's the weird thing: There wasn't really that much in the way of evidence out there. Collisions were bound to happen, sure, but it wasn't until Hubble was looking in the right place at the right time that one was caught on camera. The ill-fated couple was Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 and Jupiter, and it was a huge deal. The comet had only been discovered fairly recently, and Hubble was in the right place to watch as it broke into around 21 pieces and then hit Jupiter, all over the course of six days in 1994.

Hubble didn't just get the impact (shown by the brown spots on the photo), but dust clouds that rose nearly 2,000 miles high, storms of impact debris that took months to scatter, and a terrifying look at what's happened to Earth more than once. In addition to seeing how such a massive impact changed things like the planet's atmosphere and weather patterns, NASA says that it also catapulted science fiction into science possibility.

Suddenly, NASA could demonstrate why there was a very real need to keep an eye on Earth's skies for anything that was going to get too close. Space says it laid the groundwork for the Planetary Defense Coordination Office, which is looking for comets and asteroids that might do to Earth what Shoemaker-Levy 9 did to Jupiter. BINGO cards at the ready!