The Incredible True Story Behind The Revenant

The 2015 film "The Revenant" won multiple Oscars for its depiction of a mountain man fighting to survive in the wilderness. Both the film and the Michael Punke novel that it is based on were inspired by a genuine American frontier legend.

"Glass was a campfire legend – and it's all true," lead actor Leonardo DiCaprio told Wired. Though many of the details of Glass' life have been lost to time, the protagonist Hugh Glass was a real man. As stated in Britannica, Glass was one of countless trappers in the American West who traveled into the Rocky Mountains to bring back furs. They had to learn how to survive in the mountains and navigate the complex dynamics between the tribes that lived there. As is clear from the story of Hugh Glass, they also had to contend with wild animals.

Details about Hugh Glass' struggle for survival have very likely changed and been embellished through generations of retelling. Despite the changing details, the basic story has stayed the same as when it was first written down: a man is brutally mauled by a bear and, against all odds, makes it back to civilization to seek revenge on the men who left him to die. This is the incredible true story behind "The Revenant."

Mountain men

The term "mountain men" refers to a type of hunter that existed in the 19th century. They were trappers who traveled West in search of furs to sell – especially beaver pelts, which were coveted back on the East Coast and in Europe.

Their work took them into the Rocky Mountains where the animals were still plentiful. These men went on long expeditions and had to learn how to survive in nature under harsh conditions. Mountain men primarily learned how to live in the far West from the tribes that already lived there. As stated by Britannica, mountain men frequently adopted aspects of the culture and beliefs from the Native American communities that they interacted with. As white settlements stretched further and further west, the experienced mountain men acted as guides – but those settlements would ultimately eradicate the way of life that the mountain men had learned and push the people who had taught them off of the land.

As detailed in Edgeley W. Todd's "James Hall and the Hugh Glass Legend," the mountain man has become a highly mythologized character in American Westerns. Stories about rugged frontiersmen living in the wilderness became popular – some of which were fictional, some exaggerated, and some true.

Who was Hugh Glass?

Hugh Glass was one of the many mountain men on the hunt for beaver pelts. While his story is a classic favorite of the American West, many facts about the real man are unknown. As explained by historian Clay Landry in an interview with Irish Examiner, there is no concrete evidence for where he was born or how he grew up, though many believe he was born near Philadelphia in the early 1780s. A newspaper article published in 1825 states that it's unknown whether Glass was born in the United States or not, but that he was likely either Scottish or Irish.

As stated in a press release from the South Dakota State Historical Society-archives, it is believed that Glass was illiterate and would dictate any letters that he had to send (such as the one on display at the historical society, informing the parents of one of his fellow mountain men that their son was dead.)

The exact details of Glass' death are also uncertain. According to a report in 1839, many suspected him dead after several people, possibly from the Arikara tribe, were seen wearing clothes that used to belong to Glass, though it is worth noting that friendly trading between Native Americans and mountain men was common. It is believed that when Glass was younger, he spent time living with the Pawnee.

Pirate and Pawnee

There are many stories about adventures Hugh Glass had before the fateful trapping expedition – some just as fascinating as the one that made him famous. The only contemporary source for Hugh Glass' life before he became a trapper is the autobiography of George Yount – a fellow mountain man who stated that he knew Glass well. In his memoir, he claims that Glass was once a pirate and lived with the Pawnee. Yount's memoirs, which were eventually edited and published by the California Historical Society Quarterly, describe Glass as a veteran trapper who was "bold, daring, reckless & eccentric."

Yount claimed that Glass was a sailor before he was a trapper, and that he was taken captive by pirates. The captain of the crew was supposedly the famous pirate Jean Lafitte. Lafitte gave Glass a choice: become a part of his pirate crew or die. Glass joined the crew, but after working with the pirates for a while, he learned that Lafitte had "deemed [Glass] unfit for the work of pirates" and planned to kill him. Glass fled.

Yount also described how after leaving the pirate ship, Glass wandered the wilderness until he was found by people from the Pawnee Nation and taken captive. According to Yount, Glass presented them with a powdered red pigment called vermillion which was difficult to come by. They freed him and allowed him to travel with them. Finally, when they visited St. Louis, Glass decided to stay in the city.

100 Men

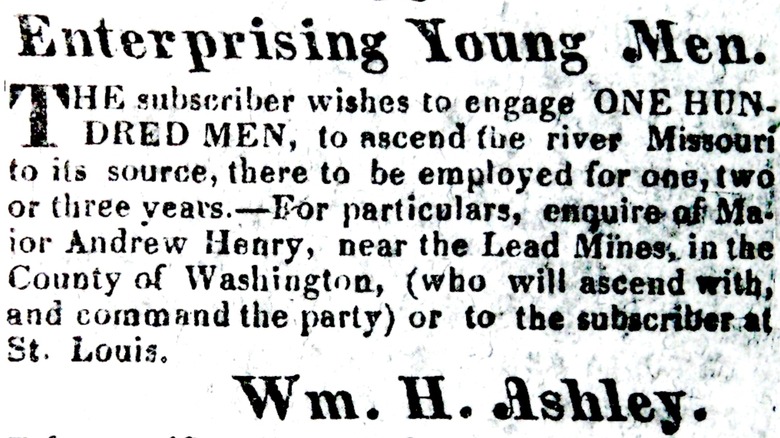

Many trappers made their living hunting beaver in the Rocky Mountains, but at least one man made his fortune – future congressman William Henry Ashley. It was an advertisement written by Ashley that attracted Hugh Glass, still living in St. Louis, to the mountain man life. As documented in "Here Lies Hugh Glass: A Mountain Man, A Bear, and the Rise of the American Nation" in 1822, an advertisement written by Ashley hit the St. Louis newspapers. He was starting his business and was looking for 100 "enterprising young men." This ad attracted several future historical figures to become fur trappers, including Jim Bridger. It was not the one that Hugh Glass responded to, however.

Ashley lost over $10,000 (the modern equivalent of almost $240,000) in goods when a keelboat unfortunately named "Enterprize" sank. He needed to hire another 100 men for 1823, and it was critical that they be successful to make up for the losses of their first year. He wrote another ad. This one lacked the implied heroism and promise of adventure that the "enterprising young men" ad had, and instead asked for hunters. The headline read: "For The Rocky Mountains."

George Laycock's "The Mountain Man" places Glass' age at around 40 years old when he would have seen this second ad. Something about it attracted him to the job, and he signed on for the expedition. He would have been one of the older mountain men. One of the youngest was Jim Bridger.

Jim Bridger

Jim Bridger, one of the "enterprising young men," who signed up to go into the mountains in search of beaver pelts, would become one of the most famous frontiersmen in the West. When he traveled with Hugh Glass, he was only a teenager, though.

Jim Bridger lived on a farm with his family not far from St. Louis. He responded to William Ashley's "enterprising young men" advertisement (via "Here Lies Hugh Glass"). As described by Britannica, Bridger continued as a mountain man for the next 20 years, and he eventually established the famous Oregon Trail stop "Fort Bridger." Multiple locations in the West, including the Bridger Mountains in Montana and Bridger National Forest in Wyoming, have been named after him.

At around 19 years old, Bridger was a part of the same trapping expedition as Glass. He would come to be one of the driving forces of Glass' harrowing journey, and one of the two men Glass would swear to get revenge on.

Conflict with the Arikara

William Ashley's second fur-trading expedition left St. Louis in early 1823. Both Jim Bridger and Hugh Glass were on it. According to the Museum of the Mountain Man, after a few months, they ran into trouble near a pair of Arikara villages. Ashley was hoping to trade there, but trappers from a rival company had recently attacked and killed several people from the village. It's possible that they believed Glass' expedition was the same trappers, or the attack had simply caused them to mistrust any mountain men passing through. There are several conflicting accounts of the events that followed, but what is known for certain is that on June 1, there was a battle. 14 of Ashley's trappers were killed, and more than 10 others were wounded, including Glass. (It was after this battle that Glass would dictate a letter to the family of one of the men who had been killed.)

The conflict would escalate into what is known as the Arikara War, but Glass did not participate. Ultimately, the United States Military negotiated a treaty with the Arikara, but after they left, trappers from the Missouri Fur Company set fire to the villages.

Now deeper in debt, Ashley split his expedition into two groups. One would retreat to Fort Kiowa, while the other traveled deep into the Rockies where they would attempt to find beavers and avoid further conflicts. Glass was one of those who continued on.

Bear attack

In late August of 1823, the party that William Ashley had sent onward (led by Major Andrew Henry) were keeping close together, fearing that the Arikara would seek retribution – except for Hugh Glass. As quoted in George Laycock's "The Mountain Man," one of the other trappers stated that Glass, "could not be restrained" and often went off on his own. The exact circumstances of what happened next vary from retelling to retelling, but what is known for certain is that one day when Glass had gone out on his own, he met with a grizzly bear.

Most versions of the story state that it was a mother bear accompanied by her cubs. Unlike in Glass' time, modern bear attacks are highly rare (as detailed in Dr. Timothy Floyd's "Bear-Inflicted Human Injury and Fatality") but even now, 80% of all bear attacks are mothers defending their cubs.

Glass was attacked by the bear. The other trapper's heard the struggle and hurried to rescue him. The bear had been killed (either by the other trappers or by Glass himself) but it seemed that they were too late to help him. According to Britannica, he sustained devastating injuries. The bear broke his leg, punctured his throat, and left him with many lacerations all over his body.

Buried alive

Far from any kind of medical help, it seemed certain that Hugh Glass would die from his injuries – it was only a matter of when. The expedition was still afraid that they would be discovered by the Arikara, or members of another local tribe. They needed to keep moving.

According to "The Man Who Returned from the Dead," they decided to spend the night there and bury Glass in the morning. When morning came, they were shocked to find that Glass was still alive, though in even worse shape than before. They constructed a litter to carry him on, but it was difficult and slowed them down. The journey was doubtless also horrendously painful for Glass. After three days, their leader, Major Andrew Henry, asked for a pair of volunteers to stay with Glass and bury him when he died. He offered "an extravagant reward," but still, few wanted to wait unguarded in dangerous territory. Finally, Jim Bridger and another trapper named John Fitzgerald agreed to stay behind.

They waited for Glass to die. Every day he seemed to grow weaker but continued to live. As time went on, the two men became more and more anxious. Many believe it was Fitzgerald who finally decided that they should abandon Glass and catch up to the rest of their party before they were discovered. Fitzgerald and Bridger took Glass' weapons and supplies. They dug a shallow grave, and as they had promised, buried Glass – but he was still alive.

Six weeks

Later, Hugh Glass told fellow trapper George Yount that after he was abandoned by John Fitzgerald and Jim Bridger he was full of "helpless rage" and became "delirious" (as quoted in the "The Man Who Returned from the Dead"). He believed that wolves came and ripped away the robe he had been covered with. He had a high fever. When he awoke again, he was still gravely injured, but he found himself stronger than he had been since the bear attacked. He swore he would find and kill Fitzgerald and Bridger.

He began a long and arduous journey back towards Fort Kiowa, which was about 250 miles away. He ate berries and insects, and drank from streams. Some accounts state that he killed and ate a rattlesnake. Some, like the one recounted by historian Clay Landry, state that he found a wolf pack hunting down a buffalo calf. After the wolves had eaten, Glass was able to take the rest of the meat for himself.

First, he crawled and then, as his injuries healed, he walked. His desire for revenge against the men who had left him for dead spurred him on. It took him about six weeks, but he made it to Fort Kiowa.

Injuries

Hugh Glass' injuries had been so severe that the other trappers had been certain he would not survive. Some versions of the story (such as the one recounted by The Dollop) describe his wounds becoming infected, and even having maggots. Despite the harsh conditions and the injuries he had suffered, Glass was able to make the long journey back to Fort Kiowa. One possible explanation for his survival is that he received help.

Some accounts state that Glass was discovered by a group of Lakota (sometimes called Sioux) who cleaned his wounds. Some versions of the legend state that Glass' back had been severely lacerated by the bear's claws and needed to be covered, and that the Lakota used the skin of the very same type of creature that had wounded him, stitching bear hide to Glass' back.

It is unknown what role, if any, the Lakota actually played in Hugh Glass' survival. Some believe that they may have even accompanied him on his legendary journey back to Fort Kiowa.

Fueled by revenge

Within a few days of reaching Fort Kiowa, Hugh Glass was trying to head back out into the wilderness. All he wanted was to track down John Fitzgerald and Jim Bridger and kill them for what they had put him through.

Because he had been one of William Ashley's mountain men, Glass was able to acquire weapons and other supplies at the fort, even though he had no money or furs to trade. As explained by historian Clay Landry for the Museum of the Mountain Man, Glass heard about a very small group of traders – just five or six men – that were planning to travel about 300 miles to trade with the Mandan. Glass believed that Bridger and Fitzgerald might be at Fort Henry, which was in the same direction. Only a few days after completing his harrowing journey to Fort Kiowa, he set off again.

The traders traveled by boat. The day before they were supposed to arrive at the Mandan villages where they hoped to trade, Glass once again insisted that he go off on his own. This time, it proved to be a wise decision. Shortly after Glass left, the traders were killed by a group of Arikara. Glass, who was walking in the direction of Fort Henry alone, was rescued by a pair of Mandan men. They helped him reach a nearby trading post, but as night fell, Glass struck out on his own again. He wouldn't give up until he found Bridger and Fitzgerald.

Finding Bridger

Glass ran into some of his fellow mountain men outside of Fort Henry. "Long was it before they could make up their minds to believe their eyes; to believe that it was the same Glass before them, whom they left, as they thought, dying of wounds," Yount wrote (via "The Man Who Returned from the Dead"), "they touched him, to ensure that it was no ghostly deception."

Glass wasn't interested in reconnecting with the other mountain men. All he cared about was finding the men who had left him to die. He soon discovered that John Fitzgerald was not there – he had abandoned the rest of the party and no one knew where he was. (According to Britannica, some accounts say that Fitzgerald joined the army.) Jim Bridger was still at the fort, however.

After surviving against incredible odds so that he could get revenge, Glass had finally found one of the men who had left him to die. Multiple accounts describe Bridger as reacting as though Glass had returned from the dead to punish him. Glass was struck when he saw Bridger for the first time not as his malevolent betrayer, but as a teenage boy. After all the time he had spent dreaming of killing Bridger, he decided to let him go.