What Being A Passenger On The Northern Pacific Railway Was Really Like

If you catch a flight at JFK International Airport in New York City, you can be to sunny California in less time than it takes to binge a season of your favorite show on Netflix. In our modern day, it's easy to take for granted this ease in which people travel throughout the world — an ease that, frankly, has not existed for very long.

If you grew up playing Oregon Trail in your elementary classrooms, you likely already know this. It was less than two centuries ago that a trip out west could last four to five months. In the game, it was a feat if you made it a month without someone contracting dysentery. There was disease, starvation, and confrontations. People died. Babies were born. The obstacles were all unpredictable. Traveling out west was, simply put, extremely dangerous.

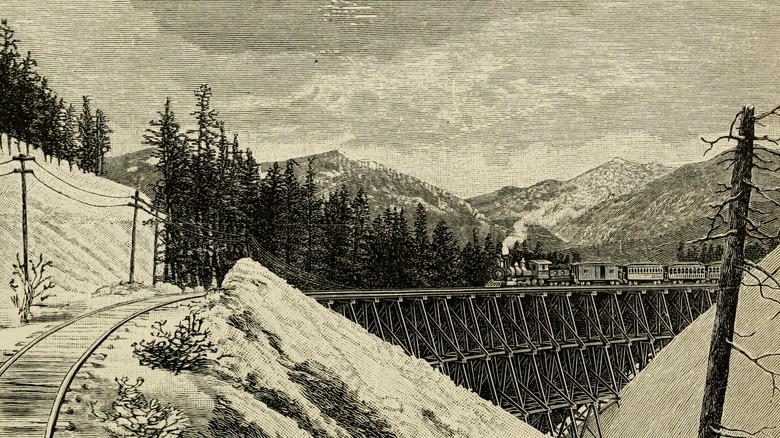

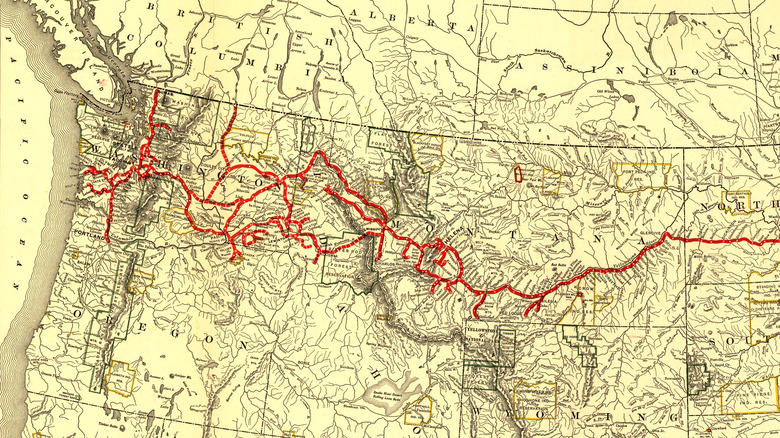

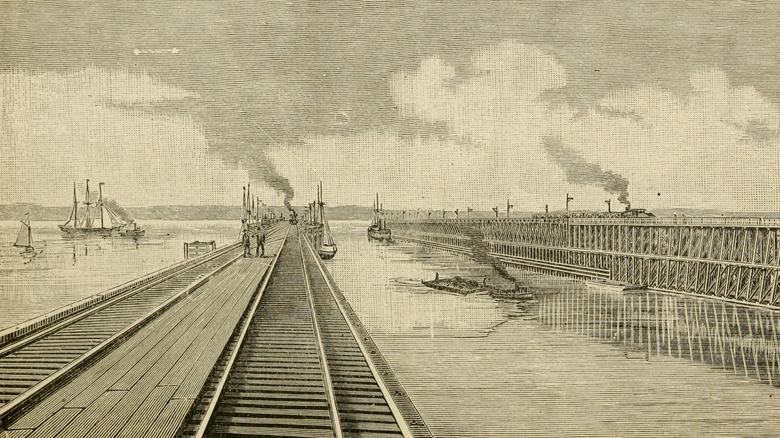

Then came the railroads. After construction of the first transcontinental railroad began, which would connect Iowa to San Francisco Bay by rail, according to the Library of Congress, there was a race to construct similar railways throughout other parts of the United States. One of these was the Northern Pacific Railway, which promised to bridge by rail the Great Lakes to the Pacific Ocean (via Britannica). While many considered such an endeavor a fool's errand and far more labor and money than it was worth, others saw opportunity. For many of those who were previously hesitant to commit to a months-long, dangerous journey by wagon, the possibility of making it across the country in mere days became irresistible.

Heading west in hopes of fortune

Whether it was the adventure of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the endless riches of the Gold Rush, or tales of cowboys living off the land, stories of the West were romanticized and mythologized in the minds of many eastern-dwelling Americans following the Civil War. There was an allure to the uncertainty and the challenges of heading westward. There was also the thrill of starting anew and, many hoped, the discovery of fortune and glory — whether through grit, determination, and hard work ... or sheer luck.

Many seeking these adventures had their eyes on the Pacific Northwest. Their means of getting there would be the Northern Pacific Railway, which beginning in 1883, promised to deliver passengers a northern passage from the Great Lakes to the Pacific. Traveling by these steam locomotives was remarkably fast. As described by History, people really began to understand this when a train made it from New York City to San Francisco in 83 hours less than a decade earlier, which had been "inconceivable to previous generations of Americans." A journey that once took months only decades earlier was condensed to a few days. If you made it to California or Oregon and found out it wasn't what you had hoped? No sweat. A train ticket east could get you back home in less than four days.

Travel guides attracted settlers out west

Of course, the creation of the railroads was not merely an act of benevolence. Those who operated the railroads expected profits. While freight service accounted for the majority of that, at its peak, 20% of the Northern Pacific's profits were generated from passenger services, according to the Northern Pacific Railway Museum.

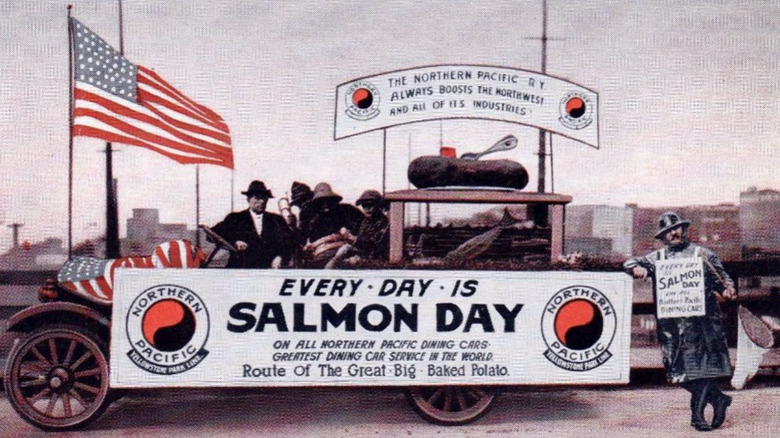

As a result, many passengers aboard the Northern Pacific Railway were attracted by a well-financed and slick marketing machine. Advertisements for their passenger services highlighted the various industries in which one could make a living out west: grazing cattle, lumbering and fishing, the mining of coal and iron, and, of course, the search for precious metals such as gold, silver, and copper.

Railway and travel guides were popular publications meant to lure not only settlers, but tourists as well. These tales, usually in thrilling first-person accounts, often exaggerated and glamorized the journey, which many would soon find out contrasted what could be the harsh reality of the trip.

First class all the way

It's Monday morning. You arrive at the Chicago train depot and begin examining travel times. If you take the express train departing in a few hours, you'll be in Livingston, Montana, by Wednesday, as per an ad in the Toledo News-Bee. You have heard from acquaintances that there was some good sight-seeing there and consider if maybe you should stay a few days before traveling the extra day to Tacoma, Washington.

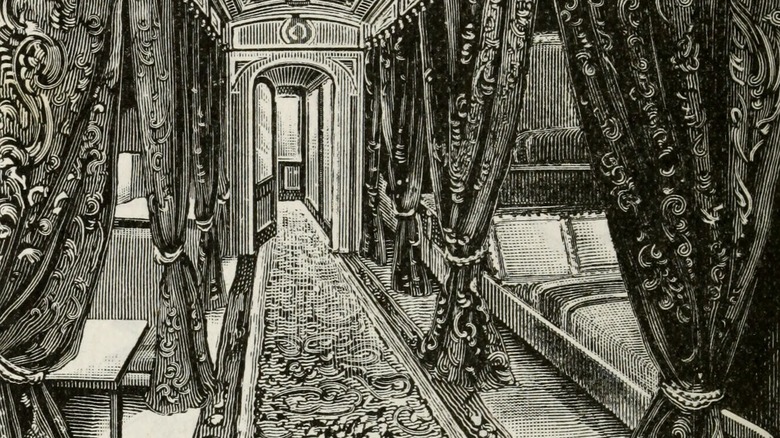

You then examine the ticket prices, noting how stark the price differences are between first-class and coach. Most of the advertisements you've seen only highlighted the luxurious first-class sleeping cars, which meant a few days of rest and relaxation. These sleeping cars, as described by Britannica, were meant for "comfortable nighttime travel," initially envisioned by George Pullman as a five-star hotel on wheels. Henry T. Williams' account, in his book, "The Pacific Tourist," of traveling by first class rail described this trip as "a constant delight" and "far more enjoyable than the saloon of a fashionable steamer" with "no fatigue or discomfort." First class wasn't cheap, but it meant entertainment, dining options, cars designed for enjoying the scenic views, and, of course, a bed at night. For those who could afford it, there were also excursion options for the various stops. This was, as reported in the Toledo News-Bee, a "new era" for passenger trains.

Of course, traveling by coach was a much different experience.

Riding the rails was no fairy tale

According to one writer who experienced the journey firsthand (via The Pullman News), traveling second class by passenger train was "no fairy tale," especially for in coach cars where one was alongside the "miners, the gold seekers, the trappers and hunters" who were "all packed like sardines in a box." He noted how it was a journey of discomfort and "fretted children," and that most only had two or three feet of personal space among a "congregation of aching spines and cramped limbs."

If riding first-class was the equivalent of a five-star hotel, then riding in a coach car was akin to bunking at a hostel — except one without beds. In coach, you'd generally sleep where you sat. You couldn't expect much privacy, and it was often louder than first class cars. Still, even with all of its discomforts, it was better than the alternative from decades prior. You would also save a significant amount of money with tickets being much less than what first class passengers paid.

Separate and definitely not equal

Passengers trains weren't only separated by class either. Coach cars were further segregated into "third class" cars. If you traveled as an African American or immigrant passenger, you often had no choice but to be placed in these segregated cars. As described by the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, many immigrants were forced onto segregated cars due to prejudiced beliefs that "they were thought to be infested with disease and vermin." These third class cars were less expensive than second class but also provided few accommodations beyond crowded benches. You would have little room for comfort, movement, or sleep.

Furthermore, a third class ticket likely meant a longer trip, sometimes as long as 10 or more days, according to History, as these third-class cars would be attached to freight cars delivering goods out west and would many times be shuffled out to make way for first class express passengers. For African American passengers, the landmark 1896 Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson that challenged the constitutionality of segregated train cars upheld their legality for over another entire generation.

Dining on the Northern Pacific railway

The Northern Pacific was the first western transcontinental railroad to have dining cars, according to Classic Trains Magazine, which debuted in 1887. The menus had a surprising variety of foods overseen by a dining car superintendent. If you were a first class passenger, you would be able to dine on the dining cars themselves with full service. Other classes of passengers had to eat their meals in their own cars.

Menu items were cooked on the train and ordered à la carte, with hearty meats such as mutton chops, sirloin steak, Salisbury steak, broiled pork chops, milk-fed chicken, and fried calf's liver with bacon. Most of these items each cost between 65 cents and $1. Side items included vegetables such as stewed corn, string beans, and baked potatoes; soups such as clam chowder, split pea, and tomato bouillon; and a variety of salads, relishes, cheeses, breads, and pastries. Drinks were 15 cents each and included coffee, tea, hot cocoa, and milk.

Later dining cars offered even more variety, with lunch options including broiled salmon, shrimp creole with steamed rice, frankfurters with spinach, and braised rib ends of beef. These also included a variety of cheaper sandwiches including club, cold ham, chicken, sardines, or toasted anchovy.

The Northern Pacific even had their own meal deal, with the "two-pound potato" for 10 cents in 1909, as per the National Railroad Museum.

When nature calls

Since this wasn't a short flight where you could simply not accept the free beverage and try to hold in your bladder, it was inevitable: You'd need to use the restroom at some point. Yet, not all toilets were created equal, and depending which decade you were riding (not to mention what class of passenger you were), the way you took care of business may have been drastically different aboard a Northern Pacific train.

In the earliest passenger trains, restrooms would be a small room with only a toilet and washbowl, as per True West Magazine. Sometimes they were open-door. As popularity of this travel increased though, demand for nicer and more private accommodations increased. While they improved only marginally for second and third class passengers (many went from being in the outright open to at least having swinging doors), first class saw more moderate improvements. An 1889 issue of Scientific American described these updates: "The ladies' toilet is a very much larger room than usual and has two wash bowls. ... The gentlemen's lavatory ... is not open, but is a private room next to the smoking room." The first class cars would also have draperies separating the toilets from the rest of the car. As for toilet paper, rolls were not yet widely in use, so most toilet paper was sold and carried in single sheet plain brown wrappers, according to True West Magazine.

A journey through Wonderland

As your journey continued, eventually you'd enter what the Northern Pacific marketed as Wonderland. Many passengers were astonished by these scenic views along this "Wonderland Route," some of which had been established as Yellowstone National Park in 1872, as per the National Parks Service. For city-folk, it likely seemed otherworldly.

"This is a world of wonders," one promotional text from 1885 by the company read, alongside a photograph of a majestic Yellowstone waterfall. "Beyond the Great Lakes, far from the hum of New England factories, far from the busy throng of Broadway, from the smoke and grime of iron cities, and the dull prosaic life of many another Eastern town, lies a region which may be designated the Wonderland of the World."

For the tourists, who were almost exclusively wealthier first-class passengers, there were excerpts on all of the sights that could be seen on excursions: the Badlands of the Dakotas, the various hot springs, Old Faithful and other geysers, and other natural wonders. They also offered deals for hunting and fishing parties and advertised various hotel accommodations for those who wished to stay and explore.

Troubles along the railway

Train robberies weren't just something from dime novels about the Old West. They really did occur on all railroads including the Northern Pacific. If you read the newspapers, you were certainly aware of this, and aboard a passenger train, no matter what class of passenger, there was likely the lingering dread of train robbers, however unlikely.

In an 1905 article from The Fulton County News, it was reported how two masked men stopped a train out of Spokane, Washington, dynamited its safes, and robbed it without ever having to fire a shot. "They wore black hats and coats and blue overalls," the article read. "Sheriffs and deputies are after the desperadoes." Fortunately, passengers were rarely directly harmed during these holdups.

There were other potential troubles as well though. As Michigan State University details, trains occasionally derailed with deadly consequence. There were also wrecks with other trains, bridge collapses, and brake failures. Then, of course, there was the fact that the railways were built without regard to the federal treaties with the many sovereign Native American nations who populated western lands. The railways displaced Indigenous peoples even further, which increased tensions, according to The Washington Post, and fueled even more distrust of the U.S. government. Not only that, but as described in Natural History magazine in 1919, the "construction of the Northern Pacific Railway hastened the extermination" of buffalo herds that many of these Indigenous nations relied on.

More women travel out west

One unexpected effect of the transcontinental railroads was the increase of women traveling out west. As long-distance passenger train rides were normalized, more women ventured into a world that had been previously dominated by men. It was an era in which "gender boundaries were being renegotiated," explains the University of Nebraska. But also from an economic perspective for the railroads, more women traveling meant more passengers and profits, so many advertisements "pictured women, vital and unrestrained, climbing mountains, riding horses, shooting wild game, playing sports, and building campfires, activities not traditionally accepted back home in the parlor."

While some women traveled with husbands and families in order to relocate permanently, numerous women, especially in the blossoming middle class, traveled solo for the experiences, some documenting their travels for publication. There was a clear sense of freedom and liberation for women in these journeys. Whatever their individual motives, for the railroad companies, there was also the belief that the presence of women travelers legitimized railroad cars as a "domesticated, and therefore moral, public setting," according to author Amy G. Richter, in her book "Home on the Rails."

Arrival in Tacoma and Seattle

For those going the entire distance, the final destination on the Northern Pacific railway was either Tacoma or Seattle, Washington, notes Seattle.gov, two growing and bustling cities with booming populations in the late 19th century. The sights, smells, and tastes would be unlike anything most recent arrivals had ever experienced.

These cities became, in the truest sense of the phrase, melting pots, with people of all ages, ethnicities, races, and nationalities converging in one place. As described by Seattle.gov, as the city surpassed 200,000 residents, Scandinavians, African Americans, and Japanese came to work in fishing, railroad service, and hotels. Large communities of Italians, Jews, Filipinos, and Chinese also sprung up in the city.

If you traveled aboard the Northern Pacific railway, whether to permanently relocate or for a sightseeing adventure, you were certainly changed by the journey. While it certainly reinforced more troubling ideas of manifest destiny and the uneven American class system and racial hierarchy, it also demonstrated the wonders of nature and the technological progress of humankind.